Pain is an unpleasant physical feeling. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines it as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”.

When there is damage to any part of your body, nerves in that part of the body send messages to your brain. When your brain receives these messages, you feel pain. This includes pain caused by cancer.

Cancer pain is a broad term for the different kinds of pain people may experience when they have cancer. Even people with the same type of cancer can have different experiences. The type of cancer, its stage, the treatment you receive, other health issues, your attitudes and beliefs about pain, and the significance of the pain to you, will also affect the way you feel pain.

Answers to some common questions about cancer pain are below.

Not everyone with cancer will have pain. Those who do experience pain may not be in pain all the time. It may come and go.

During cancer treatment, about six out of ten people (55%) say they experience some degree of pain. After treatment, about four out of ten people (39%) say they experience pain. People with advanced cancer are more likely to have pain. Advanced cancer is cancer that has spread from its original site or has come back. Nearly seven out of ten people with advanced cancer (66%) have pain.

See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27112310/

Some people with cancer have pain caused by the cancer itself, by the cancer treatment, or by other health issues not related to cancer, such as arthritis. Pain can be experienced at any stage of the disease.

Before diagnosis – Cancer can cause pain before a diagnosis and the pain may come and go. In some cases, pain comes from the tumour itself, e.g. abdominal pain from the tumour pressing on bones, nerves or organs in the body.

Diagnosis – Tests to diagnose cancer can sometimes cause short-term pain or feel uncomfortable, e.g. you may need surgey to remove a sample of tissue for examination. Most pain caused by tests can be relieved.

During treatment – Some treatments cause pain, e.g. surgery; radiation therapy leading to skin redness and irritation; and cancer drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy leading to numbness and tingling in hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy).

After treatment – Pain may continue for months or years. Causes include scars after surgery; numbness in the hands or feet (peripheral neuropathy); swelling caused by a build up of lymph fluid (lymphoedema); and pain in a missing limb or breast.

Advanced cancer – If the cancer has spread, it can cause pain by a tumour pressing on a part of the body such as a nerve, bone or organ.

There are many types of pain. Pain can be described or categorised depending on how long the pain lasts or what parts of the body are affected.

Acute pain – This is pain that starts suddenly and lasts a short time, possibly for a few days or weeks. It may be mild or severe. Acute pain usually occurs because the body is hurt or injured in some way, but it generally disappears when the body has healed.

Chronic pain – This is pain that lasts longer than three months. It may be due to an ongoing problem, but can also develop after any tissue or nerve damage has healed. It is also called persistent pain.

Breakthrough pain – This is a sudden flare-up of pain that can occur despite taking regular pain medicine for cancer pain. It may happen because the dose of medicine is not high enough or because the pain changes when the person changes position or moves around. Other causes of breakthrough pain include stress, anxiety or other illnesses.

Nerve (neuropathic) pain – This is pain caused by pressure on nerves or the spinal cord, or by nerve damage. It can come and go. People often describe nerve pain as numbness, burning or tingling, or as “pins and needles”. Nerve pain can occur anywhere nerves get damaged. For example, after breast surgery, some women

have nerve pain in the chest wall or armpit that doesn’t go away over time. This is called post-mastectomy pain syndrome. Nerve damage from some chemotherapy drugs is felt as pain in the hands and feet and is called peripheral neuropathy. Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Peripheral Neuropathy and Cancer’

Bone pain – This is pain caused by cancer spreading to the bones and damaging bone tissue in one or more areas. It is often described as dull, aching or throbbing, and it may be worse at night.

Soft tissue pain – This is pain caused by damage to or pressure on soft tissue, including muscle. The pain is often described as sharp, aching or throbbing.

Visceral pain – This is pain caused by damage to or pressure on internal organs. Visceral pain can be difficult to pinpoint. It may cause some people to feel sick in the stomach (nauseous). This type of pain is often described as having a throbbing sensation.

Referred pain – This is pain that is felt in a different area of the body from the area that is damaged (e.g. a swollen liver can cause pain in the right shoulder because the liver presses on nerves that end in the shoulder).

Localised pain – This is pain at the spot where there’s a problem (e.g. pain in the back from a tumour pressing on nerves in the area).

Phantom pain – This is a pain sensation in a body part that is no longer there, such as breast pain after the breast has been removed. This type of pain is very real.

As well as the physical cause of the pain, your environment, fatigue levels, emotions and thoughts can affect how you feel and react to pain. It’s important for your health care team to understand the way these factors affect you.

Where you are – Things and people in your environment – at home, at work and elsewhere – can have a positive or negative impact on your experience of pain.

How you feel – You may worry or feel easily discouraged when in pain. Some people feel hopeless, helpless, embarrassed, angry, inadequate, irritable, anxious, frightened or frantic. You may notice your mood changes. Some people become more withdrawn and isolated.

How tired you feel – Extreme tiredness (fatigue) can make it harder for you to manage pain. Lack of sleep can increase your pain. Ask your health care team for help if you are not sleeping well.

What you’re thinking – How you think about pain can affect how you experience the pain, e.g. whether you believe it is overwhelming or manageable.

The way cancer pain is managed depends on the cause of the pain, but relief is still possible even if the cause is unknown. Often a combination of methods is used. Options may include:

- medicines specifically for pain

- surgery, radiation therapy and cancer drug therapies

- procedures to block pain signals such as nerve blocks or spinal injections

- other therapies, such as physiotherapy, psychological support and complementary therapies

- pain management plans.

It might take time to find the right pain relief for you, and you may need to continue taking pain medicines while waiting for some treatments to take effect.

Different pain relief methods might work at different times, so you may need to try a variety. The World Health Organization estimates that the right medicine, in the right dose, given at the right time, can relieve 80–90% of cancer pain.

If you have a new pain, a sudden increase in pain or pain that doesn’t improve after taking medicines, let your doctor or nurse know. Like a cancer diagnosis, pain that is not well controlled can make you feel anxious or depressed.

The aim is for pain to be continuously controlled. You should take your pain medicine as prescribed. Sometimes this means taking pain medicine even when you don’t feel pain. If pain lasts longer than a few days without much relief, or you notice you are in more pain than usual, see your doctor. It’s better to get relief early rather than allowing it to get worse. This makes it easier to control and means you are likely to have less pain overall.

Your doctor will talk to you about how much medicine to take (the dose) and how often to take it (the frequency).

Many people believe that they should put up with pain for as long as possible and that they should only use pain medicines when pain becomes unbearable. If you do this, it can mean that you are in pain when you don’t need to be.

There is no need to save pain medicines until your pain is severe. Severe pain can cause anxiety and difficulty sleeping. These things can make the pain feel worse and harder to control.

If you think your pain medicine isn’t working or the pain returns before the next dose, it’s important to let your doctor know. They may need to adjust the dose, prescribe a different medicine or give an extra dose of medicine.

If the pain doesn’t improve the first time you use a new pain relief method, try it a few more times. If you’re taking medicine that doesn’t seem to work or has stopped working, talk to your doctor – don’t change the dose yourself.

Different health professionals help manage pain. They will often discuss ways to manage pain at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. If your pain is not well controlled, ask your general practitioner (GP) or palliative care specialist for a referral to a pain medicine specialist who is part of a multidisciplinary pain team.

Health professionals you may see

general practitioner (GP) – assists with treatment decisions; provides ongoing care in partnership with specialists

surgeon – surgically removes tumours from the body

radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

palliative care specialist – treats pain and other symptoms to maximise wellbeing and improve quality of life

pain medicine specialist – treats all types of pain, particularly ongoing pain or pain that is difficult to control

pain management team – includes pain specialist and nurses who work together to treat pain, particularly if it is difficult to control

nurse practitioner – works in an advanced nursing role; may prescribe some medicines and tests

nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support

pharmacist – dispenses medicines and gives advice about dosage and side effects

anaesthetist – provides anaesthetic medicines, monitors you during surgery, and provides pain relief during and after surgery

physiotherapist – helps with restoring movement and mobility, and preventing further injury

exercise physiologist – prescribes exercise to help people with medical conditions improve their overall health, fitness, strength and energy levels

occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities

psychologist – helps identify and manage the thoughts, emotions and behaviours that affect your pain

counsellor – helps you understand and manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment, usually in the short term

social worker – helps with emotional, practical or financial issues

Describing pain

Only you can describe your pain. How it feels and how it affects what you can do will help your health care team plan the most appropriate way to treat the pain. This is called a pain assessment. You may have regular pain assessments to see how well medicines and other ways of controlling pain are working, and to manage new or changed pain.

Questions your health care team may ask

- Where in your body do you feel pain or discomfort?

- How would you describe the pain?

- How does it compare to pain you have felt in the past?

- What does it feel like? For example, is it dull, throbbing, aching, shooting, stabbing or burning? Are there any pins and needles or tingling? Are there areas where it feels numb?

- Does your pain spread from one area to another (radiate)?

- When did the pain or discomfort begin?

- How often are you in pain? How long does the pain last each time it occurs? (Try timing the pain.) What makes the pain better or worse?

- Do you have any flare-ups of pain?

- Which activities does it prevent you from doing (e.g. getting up, dressing, concentrating, bending down, walking, sitting for long periods, exercising, carrying things, driving, sleeping, having sex)?

- What activities would you like to do if the pain improves?

- How does the pain make you feel emotionally?

- What pain relief methods have you tried? What helped or didn’t help?

- Did you have any side effects from pain medicines?

- What have you done in the past to relieve pain? How did this work? What does the pain mean to you?

Ways to describe pain

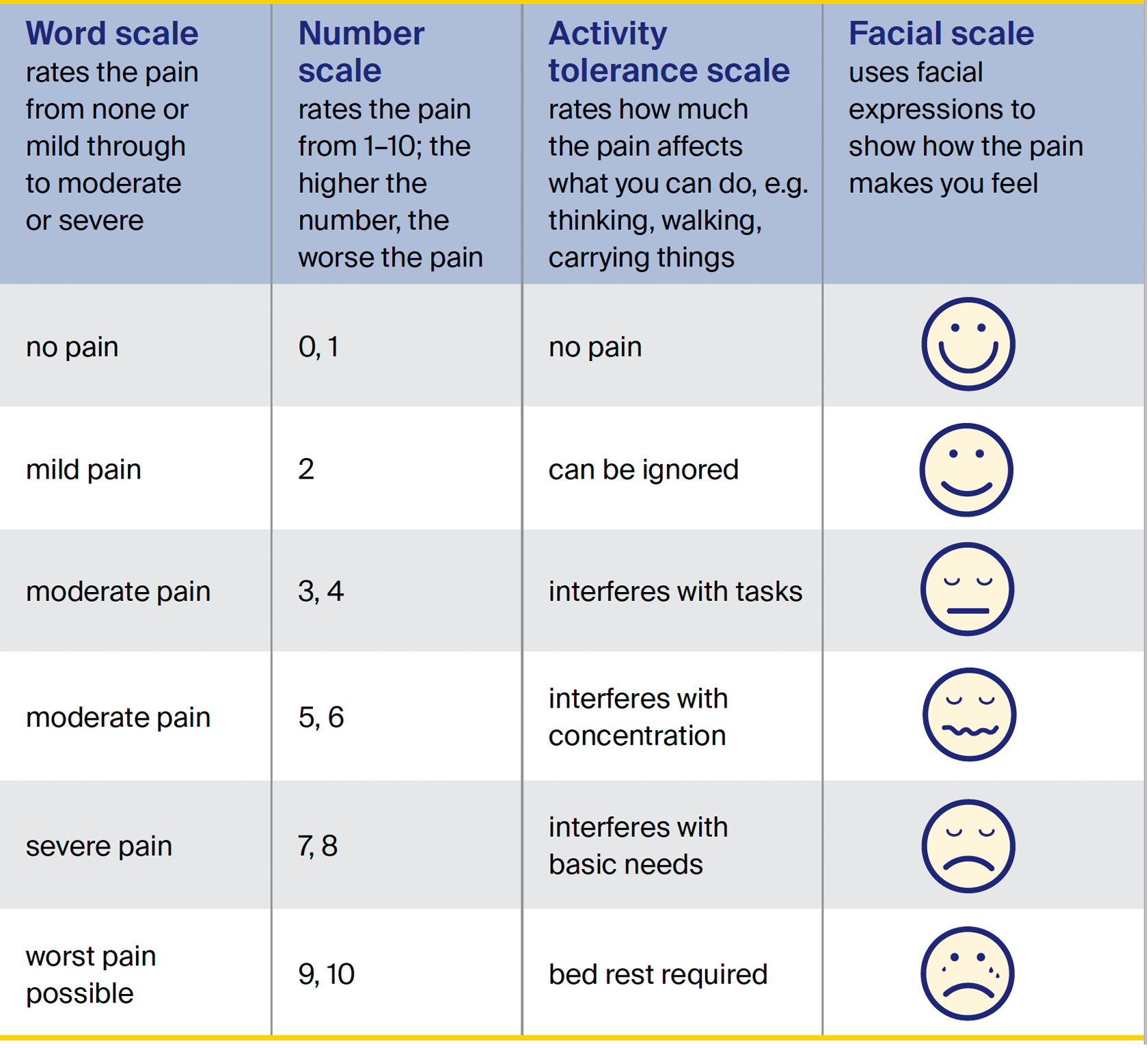

You can use different scales to describe your pain and how it is affecting you. These can help your health care team find the best pain control methods for you.

Some people rate the level of pain on a scale. There are different kinds of scales.

Write down what seems to cause or increase your pain. This is called a trigger, and it may be a specific activity or situation. Knowing what triggers your pain might help you find ways to manage these triggers.

Make a list of the health professionals in your team and their contact details. Keep this handy in case you (or your carer) need to get in touch.

A written record of your pain can help you and those caring for you understand more about your pain and how it can be managed.

Note down how the pain feels at different times of the day, what you have tried for relief and how it has worked. Some people track their pain using an app on a mobile device, such as a smartphone or tablet.

Talk to your doctors about what should prompt you to call them and who you can call, particularly after hours. For example, you may be instructed to call if you need to take four or more doses of breakthrough pain relief, or if you are feeling very sick or sleepy.

Using pain medicines

Medicines that relieve pain are called analgesics, also known as pain medicines or pain relievers. Some people also use the term painkiller, but it is not accurate to say that medicines can kill pain. Analgesics do not affect the cause of the pain, but they can help reduce pain. Different types of medicine may be used, depending on the type and level of pain. Your health care team will compare the expected pain relief against possible side effects and how the side effects might affect your quality of life. Let them know what you’d like to be able to do, e.g. “I like to be awake throughout the day”.

Types of pain control

There are different types of pain medicines.

non-opioids

- Examples include paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Often available over the counter without a prescription.

- Paracetamol is used to help with bone pain, muscle pain, pain in the skin or in the lining of the mouth.

- NSAIDs are used to reduce inflammation or swelling.

opioids

- There are different types of opioids depending on the type of pain. Opioids need a prescription.

- Examples include oxycodone, morphine and fentanyl.

adjuvant analgesics

- Can help control some types of pain.

- Often used with non-opioid and opioid medicines.

Different pain medicines take different amounts of time to work. How long each one takes depends on whether the ingredient that makes the medicine work, known as the active ingredient, is released slowly or immediately.

Slow release medicines – Also known as sustained release medicines, these release the active ingredient continuously to provide pain control over a longer period of time, often for 12–24 hours. Slow release medicines are used for constant pain and need to be taken as prescribed. This helps keep the amount of medicine in the blood high enough to work well.

Immediate release medicines – These release the active ingredient fast, usually in less than 30 minutes. Immediate release medicines are used for occasional, temporary pain (breakthrough pain) because they work quickly but for a short period of time, often for 4–6 hours.

How quickly different medicines relieve pain also varies greatly from person to person. It depends on how much medicine you take (the dose) and how often you take it (the frequency).

Pain medicines need to be taken as prescribed to control pain. This helps maintain a steady level of medicine in the body. Some people call this “staying on top of the pain”.

By taking your pain medicine regularly, even if you are not in pain, your pain may come back as mild rather than strong pain. It is important to use the correct pain medicine at the right time for it to work.

To manage your pain, your health care team may recommend a combination of prescription and non-prescription medicines. You may also consider trying complementary therapies.

Prescription medicines – These are medicines that your doctor must authorise you to take and only a pharmacist can give you (dispense). Most prescription medicines have two names:

- generic name – this identifies the chemical compounds in the drug that make it work

- brand name – this is created by the pharmaceutical company that made the medicine.

The generic name will be on the prescription, but the brand name may appear on the box. A medicine may have more than one brand name if it’s produced by different companies. For a list of some generic and brand names of strong opioids.

Non-prescription medicines – These are available without a prescription, and can be bought from pharmacies and supermarkets. They include over-the-counter medicines such as mild pain medicines and cold medicines. Vitamin supplements and herbal remedies are also considered non-prescription medicines.

Allied health services – These offer therapies, such as physiotherapy, exercises, special equipment and psychological therapies, to help people manage their pain and stay comfortable.

Complementary therapies – These are therapies that can be used alongside conventional medical treatments to improve your quality of life and wellbeing.

Pain medicines are taken in several ways, depending on the type of medicine and the form that it is available in.

tablet or capsule – This is the most common form of pain medicine. It is usually swallowed with water.

liquid – This may be an option if you have trouble swallowing tablets or for convenience.

injection – A needle is inserted into a vein (intravenously), into a muscle (intramuscularly) or under the skin (subcutaneously).

skin patch – This is stuck on your skin and gradually releases medicine into the body. Patches vary in how often they need to be changed, which may be daily, every few days or weekly – check your prescription.

intravenous infusion – Medicine is slowly injected into a vein over many hours or days using a small plastic tube and pump. If a device is attached to the infusion, you press a button to release a set dose of medicine when you need it. This is called patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

subcutaneous infusion (pump) – Medicine is slowly injected under the skin using a small plastic tube and portable pump. This can be given over many hours or days.

sublingual tablet – This is put under the tongue and dissolves without chewing or sucking.

intrathecal injection or infusion – Liquid medicine is delivered into the fluid surrounding the spinal cord. This is commonly used to treat the most severe cancer pain.

suppository – A small pellet is put into the bottom (rectum). The pellet breaks down and the medicine is absorbed by the body. A suppository may be suitable if you have nausea or trouble swallowing.

There are different ways to remember all the medicines you are taking and help ensure you take the correct dose of medicine at the right time. You can share this information with the people involved in your care.

Medicine packs – You can ask your pharmacist to organise your tablets and capsules into a blister pack (e.g. Webster-pak), which sets out all the doses that need to be taken throughout the week, along with a description of each drug.

Medicines list – This keeps all the information about your medicines together. You can record what you need to take, what each medicine is for, when to take it, and how much to take. You can:

- create your own list on paper or online

- order a printed NPS MedicineWise list to keep in your wallet or handbag

- download the MedicineWise app from the Apple Store or Google Play onto your smartphone. You can scan the barcode on packaging to add a medicine to the app and set up alarms for taking the medicine.

Family members, carers and friends sometimes have opinions about the pain relief you’re having. Your family members may feel anxious about you using pain medicines such as opioids. This may be because they are worried that you will become addicted.

Let your family know how pain affects what you can do and how you feel, and that keeping the pain under control allows you to remain comfortable and enjoy your time with them. You may want to ask your health care team if they can explain to your family and carers why a particular medicine has been recommended for you.

All medicines may have side effects, particularly if they are not taken as directed or taken for too long. Taking some medicines for too long can make pain worse.

Using different medicines together

Some medicines can react with each other, and this can change how well they work or cause side effects. Let your doctor, nurse or pharmacist know if you’re taking any other medicines at the same time as your pain relief. This includes all prescription and non-prescription medicines, vitamins, herbs and other supplements.

Many cold and flu pills and other over-the-counter medicines contain paracetamol or anti-inflammatories. These ingredients count towards your total daily dose, and you may need to take a lower dose of the pain medicine.

Medicines for colds, menstrual (period) pain, headaches, and joint or muscle aches often contain a mixture of drugs, including aspirin. People receiving chemotherapy should check with their oncologist before taking aspirin as it increases the risk of internal bleeding. Aspirin may also cause minor cuts to bleed a lot and take longer to stop bleeding.

Over-the-counter medicines for allergies may cause drowsiness, as can some pain medicines. Taking them together can make it dangerous to drive and to operate machinery.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) collects information about medicines and medical devices that haven’t worked well. You can search the Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) at tga.gov.au/database-adverse-event-notifications-daen.

Tips for using pain medicines safely

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist for written information about your pain medicines: what they are for; when and how to take them; possible side effects and how to manage them; and possible interactions with other medicines, vitamins or herbal supplements or remedies.

- Take only the prescribed dose. Do not stop taking a medicine or change the dose without talking to your doctor.

- Keep medicines in their original packaging or ask your pharmacist to put the medicines into a labelled blister pack to avoid dangerous mix-ups.

- Store medicines in a safe place that is out of reach of children.

- Write a note or set an alarm on your smartphone to remind yourself when to take your medicines.

- Ask your GP whether a pharmacist could check what medicines you’re taking and that you’re taking them correctly. This is known as a home medicines review.

- Check the expiry dates of medicines. If they are near or past their expiry, see your doctor for a new prescription.

- Take out-of-date medicines or any that you no longer need to the pharmacy for safe disposal.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist what activities are safe (e.g. driving, using machinery) when taking pain medicines.

- Call the Medicines Line on 1300 633 424 for information on medicines.

- Let your health care team know of any side effects. Call the Adverse Medicine Events Line on 1300 134 237 if you suspect you’ve had a reaction to any kind of

medicine. If you need urgent assistance, call Triple Zero (000) or go to a hospital emergency department.

You can take prescription and non-prescription medicines overseas if they’re for your personal use. A reasonable amount of medicine and medical equipment is allowed under powder, liquid, aerosol and gel restrictions.

Ways to prepare for travelling with medicines include:

- Ask your doctor if you need to change your medicine schedule to allow for time differences and if there are limits on the amount of medicines you can take overseas.

- Check with the consulates or embassies of the countries you’re visiting to make sure your medicine is legal there and if there are restrictions on how much medicine you can take with you.

- Put any medicines you need during the flight (include a few extra doses in case you are delayed) in your carry-on baggage ready for screening at the airport; pack the rest of your medicines in your checked baggage.

- Carry a letter from your doctor listing each medicine, how much you’ll be taking, and any equipment you need such as hypodermic needles or gel packs, and stating that the medicine is for your personal use.

- Keep medicines in their original packaging, which includes the label with your name, so they can be easily identified, and make sure the name on the medicines matches the name on the passport.

- Call the Travelling with PBS Medicines Enquiry Line on 1800 500 147 for more information.

Managing pain with medicines

Medicines used to control mild cancer pain include paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They are often available over the counter from pharmacies without a prescription. These types of drugs can help relieve certain types of pain, such as bone pain, muscle pain, and pain in the skin or in the lining of the mouth.

NSAIDs can reduce inflammation or swelling, and be used with stronger pain medicines such as opioids, to help relieve moderate to severe pain.

Paracetamol is a common drug that is known by various brand names such as Panadol and Panamax. It comes in many different formulations. An adult should take no more than 4 g of paracetamol in 24 hours (usually 8 tablets), unless your doctor says it’s safe to do so. For some people, a lower dose of paracetamol is recommended due to low body weight or liver problems. The maximum dose for children depends on their age and weight, so check with the doctor, nurse or pharmacist.

If taken within the recommended dose, paracetamol is unlikely to cause side effects. Some stronger pain medicines contain paracetamol along with another drug, and count towards your daily total intake. Taking too much of one type of medicine may lead to an overdose. If you are unsure whether a medicine contains paracetamol, check with your doctor, nurse or pharmacist. In some cases, your doctor will recommend you take paracetamol with other stronger pain medicines,

such as oxycodone, to help them work better.

To find out more about your pain medicine and possible side effects, read the Consumer Medicine Information included in the box of medicine or ask your pharmacist for a copy.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a group of medicines that include ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib, diclofenac and aspirin. They are known by various brand names, such as Advil and Nurofen.

You can have these medicines as tablets or sometimes as injections. Less commonly, NSAIDs are given as a suppository. Do not take more than one NSAID medicine at the same time – if you’re unsure, check with your doctor, nurse or pharmacist.

Side effects of NSAIDs

Before taking NSAIDs, ask your doctor if they are suitable for you, as some people are at higher risk of side effects.

Common side effects include nausea and indigestion. Rare side effects include a risk of bleeding in the stomach or intestines, and kidney problems. Some studies show that NSAIDs can cause heart problems, especially if used for a long time or in people who have heart problems.

Talk to your doctor or nurse before taking NSAIDs, especially if you have stomach ulcers, heart disease, kidney disease or gut reflux; are having chemotherapy; or are taking other medicines that also increase your risk of bleeding (such as anticoagulants/blood thinners like warfarin). If you are taking NSAIDs in high doses or for a long time, take them with food to lower the risk of indigestion. You can also ask about using a different type of pain medicine that is less likely to cause

indigestion and bleeding, such as paracetamol.

To find out more about your pain medicine and possible side effects, read the Consumer Medicine Information included in the box of medicine or ask your pharmacist for a copy.

Opioids

Opioids are medicines made from the opium poppy or created in a laboratory. They block pain messages between the brain and spinal cord and the body. Opioids can be used to reduce some types of pain, such as acute pain and chronic cancer pain.

There are different types of opioids and they come in varying strengths. The type you have depends on what kind of pain you have, how much pain you are in, and other factors such as how well your kidney and liver work, and whether you can take oral (by mouth) medicines. You can only have these drugs by prescription from your doctor. Codeine is an opioid that used to be commonly used for mild to moderate cancer pain. It is now only available by prescription and not often used.

Sometimes using opioids can cause more pain. This is called opioid-induced hyperalgesia. It happens because taking opioids for a long time makes specific nerves and the brain more sensitive to pain.

Working out the dose

As people respond differently to opioids, the dose is worked out for each person based on their pain level. It’s common to start at a low dose and build up gradually to a dose that controls your pain. Sometimes this can be done more quickly in hospital or under strict medical supervision. Some people do not respond to opioids.

Opioids commonly used for moderate to severe pain

You may be prescribed a combination of slow release and immediate release drugs. You may have immediate release to deal with breakthrough pain.

See below for the generic name of opioids used for moderate to severe pain and examples of their brand names.

Slow release (long-acting) opioids

fentanyl – Durogesic

hydromorphone – Jurnista

morphine – MS Contin; Kapanol; MS Mono

oxycodone – OxyContin; Targin

tapentadol – Palexia SR

tramadol – Tramal SR; Durotram XR; Zydol SR

buprenorphine – Norspan; Bupredermal; Buprenorphine Sandoz

Immediate release (short-acting) opioids

morphine – Anamorph; Ordine; Sevredol

oxycodone – Endone; OxyNorm; Proladone

hydromorphone – Dilaudid

fentanyl – Fentora; Abstral

tramadol – Tramal

buprenorphine – Temgesic

Opioids can affect people in different ways, but you may have some of the following common side effects:

Constipation – Taking opioids regularly can cause difficulty passing bowel motions (constipation). Opioids slow down the muscle contractions that move food through your colon, which can cause hard faeces (stools or poo). To keep stools soft, your treatment team will suggest you take a laxative at the same time as the opioid medicines. You may also be given a stool softener. Drinking 6–8 glasses of water a day, eating a high-fibre diet and getting some exercise can all help

manage constipation, but this may be difficult if you’re not feeling well.

Feeling sick (nausea) – This usually improves when you get used to the dose, or can be relieved with other medicines. Sometimes you may need to try a different opioid.

Drowsiness – Feeling sleepy is typical when you first start taking opioids, but usually improves once you are used to the dose. Tell your doctor or nurse if you continue to feel drowsy as you may need to adjust the dose or change medicines. Alcohol can make drowsiness worse and is best avoided. Opioids can affect your ability to drive for concerns about driving.

Dry mouth – Opioids can reduce the amount of saliva in your mouth, which can cause tooth decay or other problems. Chewing gum or drinking plenty of liquids can help. Visit your dentist regularly to check your teeth and gums.

Tiredness – Your body may feel physically tired, so you may need to ask family or friends to help you with household tasks or your other responsibilities. Research shows that stretching or a short walk helps you maintain a level of independence and can give you some energy.

Itchy skin – If you have itchy skin, sometimes it may feel so irritated that it is painful. A moisturiser may help, or ask your doctor if there is an anti-itch medicine or a different opioid you can try.

Poor appetite – You may not feel like eating. Small, frequent meals or snacks and supplement drinks may help. If the loss of appetite is ongoing, see a dietitian for further suggestions.

Breathing problems – Opioids can slow your breathing. This usually improves as your body gets used to the dose. To help your body adapt to how opioids affect your breathing, you will usually start on a low dose and gradually increase the amount. Your doctor may advise you not to drink alcohol or take sleeping tablets while you are on opioids.

Hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t there) – This is rare. It is important to tell your doctor immediately if this occurs.

Your health care team will closely monitor you while you’re using opioids. Let them know about any side effects you have. They will change the medicine if necessary.

One reason that some people don’t use opioids is because they worry about becoming addicted to opioids.

When people take morphine or other opioids to relieve acute pain or for palliative care, they may experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking a drug, but this is not addiction. A person with a drug addiction problem takes drugs to fulfil physical or emotional needs, despite the drugs causing harm.

Some people who take opioids long term for pain relief are at risk of becoming addicted. The risk is higher for people who have a history of misusing opioids or other medicines before their cancer diagnosis. People who use opioids to manage chronic pain over a long period of time are also at risk of becoming addicted. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about drug dependence.

Signs of withdrawal

If you stop taking opioids suddenly, you will usually have withdrawal symptoms or a withdrawal response. This is because your body has become used to the dose (physical dependence). Withdrawal symptoms may include agitation; nausea; abdominal cramping; diarrhoea; heart palpitations and sweating. To avoid withdrawal symptoms, your doctor will reduce your dose gradually to allow your body to adjust to the change in medicine.

Don’t reduce your dose or stop taking opioids without talking to your doctor first. They will develop a plan to gradually reduce the dose.

Not usually. Strong pain medicines are usually given by mouth as either a liquid or tablet, and work just as well given this way as injection. If you’re vomiting, opioids can be given as a suppository inserted into the bottom, by a small injection under the skin (subcutaneously), through a skin patch or in sublingual tablet form.

Opioids can also be injected into a vein for short-term pain relief, such as after surgery. This is called intravenous opioid treatment, and it is given in hospital.

Some people try to avoid taking pain medicine until the pain is severe, thinking it is better to hold out for as long as possible so the medicine works better later. However, this may change the way the central nervous system processes the pain, causing people to experience pain long after the cause of the pain is gone.

It is better to take medicine as prescribed, rather than just at the time you feel the pain.

People with cancer at any stage can develop severe pain that needs to be managed with strong opioids, such as morphine. Opioids are also commonly prescribed after surgery.

Being prescribed opioids doesn’t mean you will always need to take them. If your pain improves, you may be able to take a milder pain medicine or try other ways to manage the pain, or you may be able to stop taking strong pain medicines.

While it’s relatively common for people diagnosed with cancer to get breakthrough pain, this sudden flare-up of pain can be distressing.

You might get breakthrough pain even though you’re taking regular doses of medicine. The pain may happen on occasion or as often as several times a day. This breakthrough pain may last only a few seconds, several minutes or hours. Causes of breakthrough pain may vary. It can occur if you have been more active than usual or have strained yourself. Other causes of breakthrough pain include anxiety, or illnesses such as a cold or urinary tract infection. Sometimes there seems to be no reason for the extra pain.

Talk to your treatment team about how to manage breakthrough pain. They may prescribe an extra, or top-up, dose of a short-acting (immediate release) opioid to treat the breakthrough pain. The dose works fairly quickly, in about 30 minutes.

It is helpful to make a note of when the pain starts, what causes it and how many extra doses you need. This information will help your doctor better understand your pain experience. If you find your pain increases with some activities, taking an extra dose of medicine beforehand may help.

Some people with cancer stop getting pain relief from their usual opioid dose if they use it for a long time. This is known as tolerance. This means that the body has become used to the dose and your doctor will need to increase the dose or give you a different opioid to achieve the same level of pain control. You can develop tolerance without being addicted.

All drugs that affect the central nervous system can affect the skills needed for driving such as reaction times, alertness and decision-making. Doctors have a duty to advise patients not to drive if they are at risk of causing an accident that may harm themselves or others. While taking opioids, particularly during the first days of treatment, you may feel drowsy and find it hard to concentrate, so driving is not recommended.

Before you drive, ask your doctor for advice and consider the following:

- Don’t drive if you’re tired, you’ve been drinking alcohol, you’re taking other medicine that makes you sleepy, or road conditions are bad.

- It is against the law to drive if your ability to drive safely is influenced by a drug. Also, if you have a car accident while under the influence of a drug, your insurance company may not pay out a claim.

- Once the dose is stabilised, take care driving. Keep in mind that changes in dose or stopping opioids suddenly can affect driving, as can using breakthrough pain medicine.

- Special rules and restrictions about driving apply to people with brain tumours, including secondary brain cancer, or people who have had seizures.

- For more information, talk to your doctor or download the publication, Assessing Fitness to Drive for commercial and private vehicle drivers, from Austroads.

Stopping opioids suddenly can cause side effects. You should only reduce your dose or stop taking opioids after talking with your health care team. They will develop a withdrawal plan (called a taper) to gradually reduce the amount of medicine you take. It may take a few weeks to safely reduce the dose.

Medicinal use of cannabis

Medicinal cannabis refers to a range of prescribed products that contain the two main active ingredients, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC and CBD are cannabinoids. Other types of cannabinoids include cannabis, which is also known as marijuana, weed and pot.

Cannabinoids are chemicals that act on certain receptors found on cells in our body, including cells in the central nervous system.

There is no evidence that medicinal cannabis can treat cancer.

Research studies have looked at the potential benefits of using medicinal cannabis to relieve symptoms and treatment side effects. There is some evidence that cannabinoids can help people who have found conventional treatment unsuccessful for some symptoms and side effects, e.g. chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

To date, published studies have shown medicinal cannabis to have little effect on appetite, weight, pain or sleep problems. The International Association for the Study of Pain does not endorse the use of medicinal cannabis for pain. Research is continuing in this area.

Cannabis is an illegal substance in Australia. However, the Australian Government allows seriously ill people to access medicinal cannabis for medical reasons.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration’s Special Access Scheme allows eligible medical practitioners to apply to import and supply medicinal cannabis products. The laws about access to medicinal cannabis vary between states and territories. These may affect whether you can be prescribed this substance where you live.

For more information about medicinal cannabis, visit tga.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis.

Other medicines

To help manage pain, your doctor may prescribe medicines that are normally used for other conditions. These can work well for some types of chronic pain, particularly pain caused by nerve damage.

These medicines can be used on their own or with opioids at any stage of the cancer diagnosis and treatment. When prescribed with opioids, these drugs are known as adjuvant drugs or adjuvant analgesics. They can increase the effect of the pain medicine.

Adjuvant drugs are usually given as a tablet that you swallow. Some drugs don’t work right away, so it may take a few days or weeks before they provide relief. In the meantime, opioids are used to control the pain. If you are taking an adjuvant drug, it may be possible for your doctor to reduce the dose of the opioids. This may mean that you experience fewer side effects without losing control of the pain.

Your doctor will talk to you about any potential side effects before you start taking a new medicine.

Other medicines used to manage pain

Antidepressant

Generic names – amitriptyline; doxepin; duloxetine; nortriptyline; venlafaxine

Type of pain – burning nerve pain; peripheral neuropathy pain; electric shocks

Anticonvulsant

Generic names – gabapentin; pregabalin; sodium valproate

Type of pain – burning or shock-like nerve pain

Anti-anxiety

Generic names – diazepam; clonazepam; lorazepam

Type of pain – muscle spasms, which can sometimes occur with severe pain

Steroid

Generic names – dexamethasone; prednisone

Type of pain – pain caused by swelling; headaches caused by cancer in the brain; pain from nerves or the liver

Bisphosphonates

Generic names – clodronate; pamidronate; zoledronic acid

Type of pain – bone pain (may also help prevent bone damage from cancer)

GABA (gammaaminobutyric acid) agonist

Generic names – baclofen

Type of pain – muscle spasms, especially after spinal cord injury

Monoclonal antibodies

Generic names – denosumab

Type of pain – bone pain (may also help prevent bone damage from cancer)

Local anaesthetic

Generic names – lidocaine (lignocaine)

Type of pain – severe nerve pain

Anaesthetic

Generic names – ketamine

Type of pain – burning or shock-like nerve pain

Managing pain with other methods

Sometimes cancer pain can be difficult to relieve completely with medicines, or you may need to stop taking a pain medicine because of its side effects. If you continue to have pain, let your health care team know. There are other ways to reduce pain that don’t involve medicine. Often a combination of treatments and therapies are more effective than just one.

Cancer treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, can sometimes reduce pain by helping to remove its cause. This will depend on the cancer, the type of pain and where the pain is. Cancer treatment aimed at relieving pain, rather than curing the disease, is called palliation or palliative treatment.

Whether surgery is an option depends on several factors, including your overall health and fitness. Some people may have an operation to remove part or all of a tumour from the body. It may be a major, invasive operation or a relatively minor procedure. Surgery can improve quality of life if the pain is caused by a tumour pressing on a nerve or blocking an organ.

Examples include unblocking the bile duct to relieve jaundice (which can occur with pancreatic cancer), or removing a bowel obstruction (which can occur with ovarian or bowel cancer).

Also known as radiotherapy, this treatment uses a controlled dose of radiation, usually in the form of x-ray beams, to kill or damage cancer cells so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. This will cause tumours to shrink and stop causing discomfort. For example, radiation therapy can relieve pain if cancer has spread to the bones, or headaches if cancer has increased the pressure in the brain. When radiation is used as a palliative treatment for pain management, often only a short course of treatment of a few days to a week or two is required. The treatment team will discuss this with you.

It can take a few days or weeks before your pain improves. You will need to keep taking your pain medicines during this time. In some cases, the pain may get worse before it gets better. Your doctor will be able to prescribe different medicines to manage this. The dose of radiation therapy used to treat pain is low, and the treatment has very few side effects other than tiredness.

Drug therapies for cancer may be used to control the cancer’s growth and stop it spreading. The drugs reach cancer cells throughout the body. This is called systemic treatment, and it includes:

- chemotherapy – use of drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth

- hormone therapy – the use of synthetic hormones to stop the body’s natural hormones from helping some cancers to grow

- targeted therapy – the use of drugs to attack specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading

- immunotherapy – treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

In some cases, drug therapies can shrink tumours that are causing pain, such as a tumour on the spine that cannot be operated on. By shrinking a cancer that is causing pain and other symptoms, drug therapies can improve quality of life.

In other cases, drug therapies can reduce inflammation and relieve symptoms of advanced cancer, such as bone pain. They can also be used to prevent the cancer coming back.

Pain can sometimes be managed with other medical procedures. This can include simple options such as nerve blocks to more complex procedures such as implanted pumps. These options can be temporary or longer lasting. They are not suitable for everyone, but can be particularly useful for treating nerve pain or pain that has been difficult to control with other medicines. Ask your pain specialist to explain the risks and benefits of each procedure they recommend.

Nerve block – A nerve block numbs the nerve sending pain signals to the brain. It is usually an injection of local anaesthetic, similar to when a dentist numbs a painful tooth. Sometimes an x-ray or ultrasound machine is used to help guide the needle. In most cases, the numbing effect lasts for a few hours but it sometimes lasts for days.

A nerve block is generally used to provide short-term pain relief or to help diagnose which nerve is sending the pain signals. This can be used to help with pain after an operation.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or pulsed radiofrequency – This procedure can be used after some nerve blocks to provide longer-lasting pain relief. Pulsed RFA applies electric pulses to change how the brain senses the pain signal. Thermal RFA uses heat to damage the nerve and block it from sending pain signals to the brain. Your treating pain specialist will let you know what type of radiofrequency is most suitable. Relief from RFA is instant for some people, but for others may take up to two months to work. It can last for nine months to more than two years.

Epidural – This is an injection of local anaesthetic and sometimes other pain medicines near the nerves in the back. The pain relief can last for up to two weeks. An epidural can also be used to see if a spinal procedure is likely to help. It is sometimes offered to help with pain after an operation.

Spinal catheter with port or pump – If longer-term pain control is needed, a small tube (epidural catheter) may be placed a little deeper in the back. This is connected to an opening (port), which allows pain medicine to be dripped in continuously. If pain is likely to last longer than six months, the catheter is attached to a small pump under the skin of the abdomen (known as an intrathecal pump). This pump is refilled about every three months with pain medicine. The pump can be adjusted depending on how much pain relief you need.

Spinal cord stimulator – This is a long-lasting procedure to treat nerve pain problems. A device is implanted into the spine, and a remote control is used to send low levels of electricity. It causes tingling against the nerves in the back or neck, which reduces the amount of pain felt. The procedure is done in two steps, with the first step as a trial to see if it provides relief. If pain relief is above 60%, the second step is to permanently implant the device.

Pain medicines are often used along with other therapies to ease the discomfort of pain. These may include exercise, physical therapy, talk therapy and a range of complementary therapies. These treatments are offered by allied health professionals, such as physiotherapists, psychologists and exercise physiologists. Practitioners are usually part of your hospital multidisciplinary team (MDT), or your GP can refer you to private practitioners.

Physiotherapy and exercise techniques – An accredited physiotherapist or accredited exercise physiologist can develop a program to improve muscle strength and help you get back to some activities.

Specialised physiotherapy can help reprogram the brain to manage issues such as phantom limb pain after an amputation.

Occupational therapy – An occupational therapist can provide equipment and other devices to make you more comfortable. For example, special cushions for when you are sitting or lying down.

Psychological support – Professionals such as psychologists and counsellors can provide therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. These professionals help you understand how your thoughts and emotions affect your response to pain or identify any worries that are making the pain worse. They can help you build new coping skills and help you get back to your usual activities as much as possible.

A psychologist can teach you to use techniques such as desensitisation. This involves focusing on the pain and relaxing at the same time. Desensitisation is sometimes used for neuropathic pain (e.g. numbness or tingling). Other ways to temporarily focus on something other than the pain include counting, drawing and reading.

Complementary therapies – Complementary therapies are designed to be used alongside conventional treatments. These therapies may help you cope better with pain and other side effects caused by cancer and its treatment. They may also increase your sense of control, decrease anxiety, and improve your quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any complementary therapies you are using or thinking about trying. Depending on the conventional treatment and pain medicines you are having, some complementary therapies may cause reactions or unwanted side effects. You should also tell the complementary therapist about your cancer diagnosis, as some therapies, such as massage, may need to be adjusted to avoid certain areas of the body.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Pain after treatment

After treatment for cancer, some people will have ongoing pain for months or years. This is called chronic pain (or persistant pain) and may affect 40% of survivors.

Chronic pain may be caused by cancer treatments, cancer-related changes (e.g. reduced strength, injuries) or other conditions not related to the cancer such as arthritis. Anxiety, depression, fatigue and trouble sleeping can also make pain worse.

While opioids are sometimes prescribed for chronic pain, research shows that using opioids for a long time is not safe. However, for people with advanced cancer and who are receiving palliative care, opioids usually work well and are safe for managing cancer-related pain.

Evidence shows that opioids are not very useful or safe for managing chronic non-cancer pain. Chronic cancer pain after cancer treatment needs to be managed in a similar way to chronic non-cancer pain. This means looking at the physical, emotional and social impacts of the pain, and managing all these factors.

Your doctor may recommend you see a pain management specialist in a multidisciplinary pain clinic. The specialist can recommend a range of pain-relieving therapies and help create a pain management plan to improve your quality of life and return you to your normal activities. If the pain cannot be well controlled, the focus will shift to improving your ability to function despite the pain.

An important part of treating chronic pain is a pain management plan. This is a written document setting out your goals for managing pain, what medicines and other strategies could help, possible side effects, and ways to manage them. The pain management plan should also include details about when and who to call if you have problems.

A pain management plan is developed between the person with pain, their GP and the pain management team.

The pain management plan should be reviewed regularly. This is an opportunity to discuss any new pain, changes to existing pain and any side effects. Make sure you have a copy of the plan and share it with your health care professionals. You can download a pain management plan template here.

- Talk to your doctor about suitable medicines such as mild pain medicines and how the physical, emotional and social consequences of chronic pain affect how you cope with the pain.

- Become more actively involved in managing your pain. This has been shown to help reduce pain. Learning how pain works can help you think about the pain differently and increase your confidence to do daily activities.

- Try psychological therapies to change the way you think about and respond to pain.

- Consider complementary therapies, such as creative therapies or meditation.

- Set small goals if pain stops you from enjoying your daily activities. Gradually increase your activity, e.g. if it hurts to walk, start by walking to the front gate,

then to the corner, and then to the bus stop up the road. - Go for a walk and do some gentle stretching every day. Movement will keep your muscles conditioned and help you deal with the pain.

- Pace your activities during the day, and include rest and stretch breaks.

- Include relaxation techniques in your daily routine. These may improve how well other pain relief methods work and also help you sleep.

- Build a network of people who can help you. This may include family, friends and volunteers.

- Listen to our relaxation and meditation podcast Finding Calm During Cancer on our website or call 13 11 20 for a free copy of our relaxation and meditation recordings.

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who are dealing with pain.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, call Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636 or visit beyondblue.org.au. For 24-hour crisis support, call

Lifeline 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au.

Pain and advanced cancer

Palliative care aims to relieve symptoms of cancer and improve quality of life without trying to cure the disease. It is often called supportive care. People at any stage of advanced cancer may benefit from seeing a palliative care team.

Pain management is only one aspect of palliative care. The palliative care team may include doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, occupational therapists, psychologists and spiritual care practitioners. They work together to:

- maintain your quality of life by relieving physical symptoms

- support your emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs

- provide support to families and carers

- help you feel in control of your situation and make decisions about your treatment and ongoing care.

Your cancer specialist or nurse can put you in touch with a palliative care team for treatment in hospital or at home. This type of care can improve quality of life from the time of diagnosis and can be given alongside other cancer treatments.

Caring for someone in pain

You may be reading this information because you are caring for someone with cancer-related pain. Caring for someone who is in pain can be challenging and stressful. It’s natural to feel upset and helpless at times – it can be distressing to see someone close to you suffer.

This section answers some common questions carers might have. We hope that this information helps you provide comfort and support to the person you’re caring for. To find out more about carers’ services, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 or you can find local services, information and resources, by visiting Carer Gateway or calling them on 1800 422 737. You can also visit Carers Australia.

What if they ask for more pain medicine?

Only the person with cancer can know how much pain they feel. If you have been using a pain scale together, this can help you both communicate about the need for extra doses. The person with cancer may be having breakthrough pain and may need a top-up dose. If this occurs regularly, they should see their doctor again for advice on managing it.

If you’re still worried that the person with cancer is taking, or wanting to take, too much medicine (particularly if the medicine is an opioid) talk with their doctor about the dose they can safely have and other ways to help manage the pain.

Should I keep opioids locked up?

It is important to keep opioids away from children and other members of your household or visitors. You can put them in a high cupboard or a secure place.

Can a person taking opioids sign legal documents?

When someone signs a legal document, such as a will, they must have capacity. This means they must be aware of what they are signing and fully understand the consequences of doing so. If they lack capacity, the documents can be contested later.

If a person’s ability to reason is affected by taking opioids, it makes sense to delay important decisions until the impairment has passed. Ask your GP or specialist to assess whether the person with cancer is fit to sign a legal document or talk to a lawyer about this before any document is signed.

When should I call the medical team?

Call a doctor or nurse for advice if the person with cancer:

- becomes suddenly sleepy or confused

- hasn’t had a bowel motion for three days or more

- is vomiting and cannot take the pain relief

- has severe pain despite top-up doses

- is having difficulty taking the medicine or getting prescriptions filled

- experiences other symptoms that the treatment team has mentioned, such as hallucinations with particular drugs.

What if they lose consciousness?

If the person with cancer becomes unconscious suddenly, call Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance immediately. Do not give opioids to an unconscious or very drowsy person.

Featured resource

This information was last reviewed August 2021 by the following expert content reviewers: Dr Tim Hucker, Pain Medicine Specialist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Dr Keiron Bradley, Palliative Care Consultant, Bethesda Health Care, WA; A/Prof Anne Burke, Co-Director Psychology, Central Adelaide Local Health Network, President, Australian Pain Society, Statewide Chronic Pain Clinical Network, SA, School of Psychology, The University of Adelaide, SA; Tumelo Dube, Accredited Pain Physiotherapist, Michael J Cousins Pain Management and Research Centre, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW; Prof Paul Glare, Chair in Pain Medicine, Palliative Medicine Specialist, Pain Management Research Institute, The University of Sydney, NSW; Andrew Greig, Consumer; Annette Lindley, Consumer; Prof Melanie Lovell, Palliative Care Specialist HammondCare, Sydney Medical School and The University of Technology Sydney, NSW; Caitriona Nienaber, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA; Melanie Proper, Pain Management Specialist Nurse Practitioner, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD; Dr Alison White, Palliative Medicine Specialist and Director of Hospice and Palliative Care Services, St John of God Health Care, WA. We also thank the writers of the original edition of this title, Prof Melanie Lovell and Prof Frances Doyle.