About this information

This information has been prepared to help you understand more about radiation therapy, one of the main treatments for cancer. Radiation therapy is also known as radiotherapy.

We cannot give advice about the best treatment for you. You need to discuss this with your doctors. However, this information may answer some of your questions and help you think about what to ask your treatment team. It may also be helpful to download the Cancer Council booklet about the type of cancer you have.

How cancer is treated

Cancers are usually treated with surgery, radiation therapy (radiotherapy) or chemotherapy. Other drug treatments, such as hormone therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy, can also be used to treat some types of cancer.

These treatments may be used on their own, in combination (e.g. you may have chemotherapy together with radiation therapy), or one after the other (e.g. radiation therapy first then surgery).

Types of cancer treatments

Radiation therapy

The use of a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. Treatment aims to affect only the part of the body where the radiation is targeted.

Drug therapies

Drugs can travel throughout the body. This is called systemic treatment. Drug therapies include: • chemotherapy – the use of drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth • hormone therapy – drugs that block the effect of the body’s natural hormones that cause some types of cancer to grow • immunotherapy – treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer • targeted therapy – drugs that target specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing or spreading.

Surgery

An operation to remove cancer and/or repair a part of the body affected by cancer.

Your treatment plan

Cancer treatment is tailored to each person. Your treatment plan will be different from other people’s, even if their cancer type is the same. The treatments recommended by your doctor depend on:

- the type of cancer you have

- where the cancer began (the primary site)

- whether the cancer has spread to other parts of your body (metastatic or secondary cancer)

- your overall health, fitness and age

- what treatments you want to have and what treatments are available

- whether there are any suitable clinical trials.

Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to order our free booklets or download the information about different cancer types and their treatments.

Radiation therapy for children

The information on these pages is for adults having radiation therapy. Much of it will also be relevant for children.

Talk to your treatment team for specific information about radiation therapy for children, and check out:

Cancer Hub – Provided by Canteen, Redkite and Camp Quality, this website helps families affected by cancer (with children aged up to 25 years) get support. Call 1800 431 312 or visit Cancer Hub.

Cancer Australia Children’s Cancer – For information about how children’s cancers and how they are treated.

Talking to Kids About Cancer – Explaining a cancer diagnosis to kids can feel overwhelming. This information provides a starting point for these often-challenging conversations. Call 13 11 20 for your free copy.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about radiation therapy are below.

What is radiation therapy?

Radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. Most forms of radiation therapy use focused, high-energy x-ray beams (also known as photons). Radiation can also be electron beams, proton beams, or gamma rays from radioactive sources. Radiation therapy is a localised treatment. This means it generally affects only the area being treated.

When is radiation therapy used?

It is estimated that radiation therapy would be a suitable part of treatment for 1 in 2 people with cancer. The Guides to Best Cancer Care set out the recommended treatment pathways in Australia for many types of cancer. For some cancers, radiation therapy is recommended as the most effective approach, either on its own or in combination with other treatments. For other cancers, other treatments may be more effective.

How does radiation therapy work?

Radiation therapy aims to kill or damage cancer cells in the area being treated. Cancer cells begin to die days or weeks after treatment starts, and continue to die for weeks or months after it finishes. Treatment is carefully planned to do as little harm as possible to healthy cells near the cancer. Most of these healthy cells receive a lower dose and can usually repair themselves.

Why have radiation therapy?

Radiation therapy can be used for different reasons:

To achieve remission or cure – Radiation therapy may be given as the main treatment to make the cancer reduce or disappear. This is known as curative or definitive radiation therapy. Sometimes definitive radiation therapy is given together with chemotherapy to make it work better. This is called chemoradiation.

To help other treatments – Radiation therapy is often used before or after other treatments. If used before (neoadjuvant therapy), the aim is to shrink a tumour. If used after (adjuvant therapy), the aim is to kill any remaining cancer cells.

To relieve symptoms – Radiation therapy may be used to make the cancer smaller or stop it spreading. This is known as palliative radiation therapy. It can help relieve pain and other symptoms.

Will I have side effects?

If radiation therapy injures healthy cells near the treatment area, side effects may occur. The side effects you have will vary depending on the part of the body treated, the dose of radiation and the length of treatment. Most side effects are temporary and tend to improve gradually in the weeks after treatment ends.

"I read a lot about all the negative side effects you might get from radiation therapy, but I’ve had no long-term side effects.”

DEREK

What is chemoradiation?

Chemoradiation means having radiation therapy at the same time as chemotherapy. It is also known as chemoradiotherapy.

The chemotherapy drugs make the cancer cells more sensitive to the radiation. Having radiation therapy and chemotherapy together is more effective for some cancers.

Chemoradiation is only helpful for some cancer types. If you have chemoradiation, your treatment team will talk to you about your treatment plan. You may have chemotherapy and radiation therapy at different times on the same day or on separate days.

The side effects of chemoradiation will vary depending on the chemotherapy drugs you have, the dose of radiation, the part of the body being treated and the length of treatment. Your treatment team will talk to you about what to expect and how to manage any side effects.

Which health professionals will I see?

During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your cancer care.

The main specialist doctor for radiation therapy is a radiation oncologist. You may be referred to a radiation oncologist by your general practitioner (GP) or by another specialist such as a surgeon or medical oncologist.

Treatment options will often be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. You may also see some allied health professionals to help you manage any treatment side effects.

Health professionals you may see

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiation therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy to the radiation oncologist’s prescription

Radiation oncology nurse – provides care, information and support for managing side effects and other issues throughout radiation therapy

Medical physicist – ensures treatment machines are working accurately and safely; oversees safe delivery of radionuclide therapy; monitors radiation levels

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Surgeon – surgically removes tumours and performs some biopsies

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Speech pathologist – helps with communication and swallowing difficulties during treatment and recovery

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Psychologist/counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

Physiotherapist, exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve fitness and wellbeing

Lymphoedema practitioner – educates people about lymphoedema prevention and management, and provides treatment if lymphoedema occurs

How is radiation therapy given?

There are 2 main ways of giving radiation therapy – from outside the body or inside the body. You may have one or both types of radiation therapy, depending on the cancer type and other factors.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) – The process is similar to having an x-ray. You will lie on a treatment table underneath a large machine that moves around your body. Radiation beams from the machine are precisely aimed at the area of the body where the cancer is located. The beam operates for a few minutes only. You won’t see or feel the radiation, although the machine can make noise as it moves.

Internal radiation therapy – A radiation source is placed inside the body or, more rarely, injected into a vein or swallowed. The most common form of internal radiation therapy is brachytherapy, where temporary or permanent radiation sources are placed inside the body next to or inside the cancer.

Where will I have treatment?

Radiation therapy is usually given in the radiation oncology department of a hospital or in a treatment centre. This may be in the public or private health system.

Most people have radiation therapy as an outpatient. This means you do not stay in hospital, but travel to the hospital or treatment centre for each session. It’s a good idea to think about how you will get to each session. For some types of internal radiation therapy, you may need to stay in hospital overnight or for a few days.

What are the steps in radiation therapy?

Consultation session

You will meet with a radiation oncologist. They will check your test results, assess your fitness for treatment, explain the process and expected results, and discuss possible side effects and risks. You will be asked to agree (consent) to have treatment.

Planning (simulation) session

You will meet with a radiation therapist. They will work out how to best position your body during EBRT or where to place the applicators for brachytherapy.

Treatment plan

Based on the planning session and the treatment guidelines for the cancer type, the radiation

oncologist, radiation therapist and medical physicist will work out the radiation dose, what area needs to be treated and how to deliver the right dose of radiation.

Treatment sessions

Radiation therapists will deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan. How long each treatment session takes will depend on the type of radiation therapy.

Review and follow-up

You will have regular reviews with the treatment team to discuss how to manage any side effects and assess how you have responded to treatment.

How many treatment sessions will I have?

Radiation therapy is tailored to your situation. The number of treatment sessions recommended by your radiation oncologist will depend on the type of cancer you have.

Based on treatment guidelines, your radiation oncologist will work out the total dose of radiation needed to treat the cancer. In most cases, the total dose is broken up into a number of smaller doses called fractions. Each fraction of radiation is given in one treatment session.

The whole course of radiation therapy may be given over a number of days or weeks. Some people have one treatment session, other people may have treatment once a day, Monday to Friday, for several weeks. Some people have radiation therapy twice a day and others have treatment sessions a week apart. Your radiation oncologist will talk to you about your treatment schedule.

Treatment schedules will continue to change as research shows what works best to kill cancer cells and lessen side effects.

Most cancers have treatment protocols that set out the total dose of radiation, the fractions, and the treatment schedule. Your specialist may need to tailor the protocols to your individual situation. You can find treatment protocols at eviQ.

How much does radiation therapy cost?

It is your choice whether you have treatment in the public or private health system. If you have radiation therapy as an outpatient in a public hospital, Medicare pays for your treatment.

Medicare also covers some of the cost of radiation therapy in private treatment centres, but you may have to pay the difference between the cost of treatment and the Medicare rebate (gap payment). Private health insurance does not usually cover radiation therapy because it’s considered an outpatient treatment.

Before treatment starts, ask your provider for a written quote that shows what you will have to pay. If you are concerned about the cost, you may want to ask for a referral to a public centre for treatment.

Will I be able to work?

During radiation therapy, you are likely to feel well enough to continue working and doing your usual activities. As you have more sessions, you may feel more tired or lack energy.

Whether you will be able to work depends on:

- the type of radiation therapy you have

- whether you are having chemotherapy at the same time

- how you feel

- the type of work you do.

Ask your treatment team if they offer very early or late appointments so that you can fit your treatment sessions around your work.

Let your employer know how much time you are likely to need off work. Explain that it is hard to predict how radiation therapy will affect you, and discuss the options of flexible hours, modified duties or taking leave.

How do I prepare for radiation therapy?

Radiation therapy affects everyone differently, so it can be hard to know how to prepare for treatment. The suggestions below may help you cope with radiation therapy. You can also talk to the social worker at the treatment centre to find out what support is available.

Ask about fertility – Some types of radiation therapy affect fertility. If you think you may want to have children in the future, talk to your treatment team about your options before radiation therapy begins.

Download our booklet ‘Fertility and Cancer’

Explore ways to relax – While you wait for treatment, read a book or listen to music, ask a friend or family member to keep you company, or try chatting to other people. To help you relax during the session, try breathing exercises or meditation. You could also listen to music or our relaxation and meditation podcast ‘Finding Calm During Cancer‘.

Organise help at home – Support with housework and cooking can ease the load. If you have young children, arrange for someone to look after them during radiation therapy sessions. Older children may need someone to drive them to and from school and activities. Ask a friend or family member to coordinate offers of help, or use an online tool such as Gather my Crew.

Look after yourself – Try to eat nourishing food, drink lots of water, limit the amount of alcohol you drink, get enough sleep, and balance rest and physical activity. Regular exercise and good nutrition can help reduce some of the side effects of radiation therapy.

Discuss your concerns – Keep a list of questions and add to it whenever you think of a new question. If you are feeling anxious about having radiation therapy, talk to the treatment team, your GP, a family member or friend, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Consider quitting – If you smoke or vape, it is important to stop smoking before starting treatment. Smoking or vaping may affect how well the treatment works and may make side effects worse. If you need support to quit smoking, talk to your doctor or call the Quitline on 13 7848.

Check other medicines – Some over-the-counter medicines, alternative and home remedies, herbs, vitamins and creams can affect how radiation therapy works and increase skin reactions. Ask your radiation oncologist whether you need to stop taking or using any herbs, creams or supplements before treatment.

Check your teeth – If you are having radiation therapy for a cancer in the head and neck area, you may need a dental check‑up before treatment starts. The dentist can check for any decaying teeth and advise if they need to be removed before you start treatment.

Arrange transport and accommodation – Plan how you will get to radiation therapy sessions. If travelling by car, ask about parking. If you feel tired as the treatment goes on, you may want to arrange for someone to drive you. If you have to travel a long way for treatment, you may be eligible for financial assistance to help cover the cost of travel or accommodation. A social worker can help you apply or you can call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

Mention medical implants – Let your treatment team know if you have any medical devices in your body. This may be a pacemaker, cochlear implant, or a hip or knee replacement. Radiation therapy can affect these devices or be affected by them.

Can I have radiation therapy if I’m pregnant?

You probably won’t be able to have radiation therapy if you are pregnant, as radiation can harm a developing baby. It’s also important that you don’t become pregnant during the course of treatment.

If at any time you suspect you may be pregnant, it is important to tell your doctor. If you are breastfeeding, ask your doctor whether it is safe to keep breastfeeding while you’re having radiation therapy.

It is recommended that people who have radiation therapy to the pelvic area use contraception to avoid getting their partner pregnant during treatment and for about 6 months afterwards, as radiation therapy can damage sperm. Your doctor will be able to give you more information about radiation therapy and pregnancy.

How will I know the treatment has worked?

Because cancer cells continue to die for weeks or months after treatment ends, your radiation oncologist most likely won’t be able to tell you straightaway how the cancer is responding. You may not know the full benefit of having radiation therapy for some months.

If radiation therapy is given as palliative treatment, the relief of symptoms is a good sign that the treatment has worked. This may take a few days or weeks. Until then, you may need other treatments for your symptoms, such as pain medicine.

What imaging scans are commonly used?

During planning and treatment, you may need to have some of the following imaging scans to show the exact position and shape of the cancer. Your treatment team will explain what to expect from each scan.

x-ray

- low-energy beams of radiation pass through the body and create an image on x-ray film

- you hold still while a machine takes images ultrasound

- uses soundwaves to create pictures of internal organs

- a small device called a transducer sends out the soundwaves as it is moved over an area of your body

CT scan (computerised tomography)

- uses x-ray beams and a computer to create detailed pictures of the inside of the body

- before the scan, you may have an injection of dye into one of your veins to make the pictures clearer

- you lie on a table that moves in and out of the scanner

PET scan (positron emission tomography)

- uses a low-dose radioactive solution to measure cell activity in different parts of the body

- before a PET scan, you will be injected with a solution containing a small amount of radioactive material

- cancer cells absorb more of the solution and show up brighter on the scan

PET–CT scan

- combines a PET scan and a CT scan in one machine to provide more detailed information about the cancer

MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging)

- uses a magnet and radio waves to build up detailed pictures of an area of the body

- before the scan, a dye may be injected into a vein to make the pictures clearer

- you will lie on a table that slides into a large metal tube

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

External beam radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common type of radiation therapy. It directs high-energy radiation beams at the cancer.

How EBRT works

EBRT is delivered using a radiation machine. The most common type is a linear accelerator (LINAC). You will lie on a treatment table or “couch” under the machine. The machine does not touch you, but it will rotate around you to deliver radiation to the area with cancer from different directions. This allows the radiation beam to be more precisely targeted at the cancer and limits the radiation given to surrounding normal tissues. The radiation beam is on for only a few minutes and you won’t see or feel anything.

Common types of EBRT

EBRT can be given using different techniques and types of radiation. The radiation oncologist will recommend the most suitable method for you. If you need a type of radiation therapy that is not available at your local hospital, they may arrange for you to have it at another centre.

Most machines use imaging scans before and during treatment to check you are in the correct position. This is known as image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT). It may use x-rays, a CT scan or an MRI scan.

Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3DCRT) – This is the basic form of modern EBRT using a LINAC. It shapes (conforms) the radiation beam to fit the treatment area.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) – This is a highly accurate type of conformal radiation therapy. It shapes and divides multiple beams of radiation into tiny beams (beamlets) to closely fit the tumour while healthy tissue nearby receives lower doses of radiation.

Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) or rapid arc – This is a more advanced type of IMRT. As the machine moves around you, it reshapes and changes the intensity of the radiation beam.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and stereotactic radiation therapy (SRT) – These are specialised types of radiation therapy used for brain tumours, not a type of surgery. Many small beams of radiation are aimed at the tumour from different directions to target the exact shape of the tumour. It may be delivered by a different type of machine, such as a Gamma Knife or CyberKnife.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) – Also known as stereotactic ablative body radiation therapy (SABR), this method combines many small beams of radiation from different angles to target the exact shape of the tumour. It may be delivered by a different type of machine, such as a Gamma Knife.

The radiation therapy department was able to schedule sessions for first thing in the morning to fit in with my work schedule. The sessions were really quick and I was able to drive straight to work afterwards. As a working mum, being able to continue going to work was so beneficial … having the support of my colleagues was invaluable.

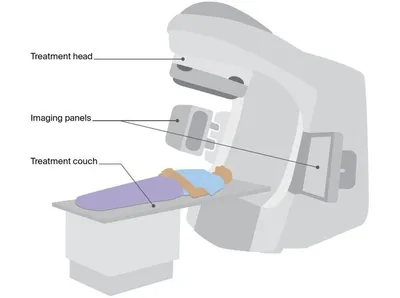

Linear accelerator (LINAC)

This is a general illustration of a LINAC, the most commonly used machine for delivering EBRT. The LINAC used for your treatment may look different.

A LINAC is large and often kept in a separate room. An imaging device, such as a CT imaging panel, is usually attached to the LINAC. This helps position you accurately on the couch so that the correct area of the body receives the radiation. The radiation beam comes out of the treatment head, which moves around you while you lie still on the couch.

Planning EBRT treatment

EBRT needs to be carefully planned to ensure that enough radiation reaches the cancer, while as little radiation as possible reaches healthy tissues and organs. The planning steps below may take place over a few appointments.

Consultation session

- This may take up to 2 hours.

- To assess whether radiation therapy is the right treatment for you, the radiation oncologist will talk to you and look at all your test results and scans. They may do a physical exam.

- The radiation oncologist will then explain how radiation therapy will help you, what will happen during planning and treatment, and what side effects to expect.

- You will also meet the radiation oncology nurse and a radiation therapist. They can provide support and further information. They will usually explain what side effects to expect and how to manage them.

- The radiation oncologist may arrange further x-rays, scans or other tests to find out more about the cancer.

- Consider taking a family member or friend with you to keep you company, ask questions and make notes.

- Ask what you will have to pay for treatment.

Planning (simulation) session

- This is usually done soon after the consultation session. It lets your treatment team work out how to direct the radiation and best position your body for treatment.

- You will have a planning scan. It may be a CT, MRI or PET scan.

- You will have the planning scan in the same position you will later be placed in for treatment.

- If you are having radiation to the chest area, you may need to hold your breath during the planning scan. You may also have a special CT scan, called a 4DCT, to track your breathing, or be taught how to take deep breath holds.

- If you are having radiation therapy to the pelvic area, the size of your bladder and bowel will be checked during the scan. You may be asked to drink a set amount of water before each treatment session to make sure the bladder is full and the area having treatment is in the same position each time. You might also be asked to empty your bladder or bowel.

- The images are sent to a special computer that lets the radiation oncologist and radiation therapists work out how to direct the radiation.

After the planning session, your radiation oncologist will work out the total dose of radiation needed and the total number of treatments. This can take a few hours for urgent treatment or several days to weeks depending on your treatment needs.

Helping you stay still

- You may need some type of device to help you stay in exactly the same position for each treatment session and keep still for around 5–10 minutes.

- This is known as an immobilisation device. It will be made during the CT planning session. Depending on the area being treated, the device could be a breast board, a knee or foot cushion, or a bag that moulds to the shape of your body.

- For radiation therapy to the head or neck area, you may need to wear a plastic immobilisation mask. This will be made to fit you. A mask can feel strange and confining, but you will still be able to hear, speak and breathe.

- Some centres offer surface guided radiation therapy (SGRT). This uses special cameras to position you on the table and monitor your body’s movements during treatment. This means you won’t need an immobilisation device or skin markings.

Markers

- To make sure you are in the same position each session, a few permanent ink spots (tattoos) may be marked on your skin. These tattoos are the size of a small freckle and can’t be easily seen.

- Sometimes temporary ink marks are made on the skin. Ask the radiation therapists if you can wash these marks off or if you need to keep them until the end of the treatment. The ink may be redrawn during the course of treatment, but it will gradually fade. Invisible tattoos may also be available.

- If you have to wear a mask or cast, the markings may be made on this device rather than on your skin.

- To help with image-guided radiation therapy, as well as tattoos you may have a surgical procedure to insert small markers into or near the cancer. The markers (called fiducials) are made of gold and are about the size of a grain of rice. These markers can be seen on scans during treatment.

What to expect at treatment sessions

You will usually start radiation therapy a few days or weeks after the planning session. Your treatment team will let you know what time to arrive and how long you will need to be in the radiation therapy department. There will be at least 2 radiation therapists at each treatment session. You may be asked to change into a hospital gown and remove any jewellery before you are taken into the treatment room.

Positioning you for treatment – The treatment room may be in semi-darkness so the therapists can see the light beams from the treatment machine and line them up with the tattoos or marks on your body or mask.

After the radiation therapists position you on the treatment couch, they will leave the room to take some imaging scans using the imaging device attached to the treatment machine. They will check the scans and make any adjustments needed to make sure you are in the same position as you were during the planning session. This may mean moving the table from outside the room or coming back into the room to move your body.

Receiving the treatment – Once you are in the correct position, the radiation therapists will control the treatment machine from a nearby room. They can see you on a television screen and you can talk to them over an intercom. The lights can be on during treatment.

The machine will move around you but it will not touch you. You won’t see or feel the radiation but you may hear a buzzing noise from the machine while it is working and when it moves.

The radiation therapists may turn off the machine and come into the room to change your position or adjust the machine.

Keeping still – It is important to stay very still to ensure the treatment targets the correct area. The radiation therapists will tell you when you can move. You will usually be able to breathe normally during the treatment. For treatment to some areas, such as the chest, you may be asked to take a deep breath and hold it while the radiation is delivered.

How long – The treatment itself takes only a few minutes, but each session of EBRT may last around 10–40 minutes because of the time it takes the radiation therapists to set up the equipment, place you into the correct position and do the imaging scans. The first session may take longer while checks are performed. You will be able to go home once the session is over.

Managing discomfort – EBRT is painless and you won’t feel it happening. If you feel discomfort when you’re lying on the treatment table, tell the therapists – they can switch off the machine and start it again when you’re ready. If you’re in pain because of the position you’re in or because of pain from the cancer, talk to the radiation oncology nurse. They may suggest you take pain medicine before each session.

Some people who have treatment to the head say they see flashing lights or smell unusual odours. These effects are not harmful, but tell the radiation therapists if you have them.

Taking safety precautions – EBRT does not make you radioactive because the radiation does not stay in your body after each treatment session. You will not need to take any special precautions with bodily fluids (as you would with chemotherapy). It is safe for you to be with other people, including children and pregnant women, and for them to come to the radiation therapy centre with you. However, they cannot be in the room during the treatment.

After the treatment session – You will see the radiation oncologist, a registrar (a hospital doctor training to be a radiation oncologist) or a radiation oncology nurse regularly to check your progress and discuss any side effects.

Specialised types of EBRT

Total body irradiation (TBI) – This is a form of radiation therapy that’s given to the whole body for blood cancers. Sometimes TBI is given with chemotherapy to prepare people for a stem cell or bone marrow transplant. You will be admitted to hospital to have TBI. A course of TBI may be given as one dose or as several doses over a few days. Your treatment team will talk to you about your treatment schedule and any side effects you may have.

Proton therapy – This uses radiation from protons rather than x-rays. Protons release most of their radiation within the cancer. This is different to standard EBRT beams, which pass through the area and nearby healthy tissue. Special machines called cyclotrons and synchrotrons are used to generate and deliver the protons. Proton therapy may be useful when the cancer is near sensitive areas, such as the brain stem or spinal cord.

Proton therapy is not yet available in Australia (as at March 2024), but there is government funding to allow Australians with specific cancer types to travel overseas for treatment. Your radiation oncologist can advise if you are eligible and provide more details. A centre to deliver proton therapy in Australia is under construction. When complete, the Australian Bragg Centre for Proton Therapy and Research in Adelaide will treat some childhood and rare cancers.

Managing anxiety before and during EBRT

The radiation therapy machines are large and kept in an isolated room. This may be confronting, especially at your first treatment session.

You may feel more comfortable as you get to know the staff, procedures and other patients.

If you are having radiation therapy for a head and neck or brain cancer, you may have to wear a plastic mask made of tight-fitting mesh. Wearing the mask makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic.

Tell the radiation therapists if you feel anxious or claustrophobic before or during treatment.

With the support of the radiation therapy team, many people find that they get used to wearing the mask.

The team may suggest you try breathing or relaxation exercises, or listening to music to help you relax. A mild sedative may also help.

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy is the most common type of internal radiation therapy. It is used to treat some types of cancer, including breast, cervical, prostate, uterus and vaginal. As with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), the main treating specialist for brachytherapy is a radiation oncologist. How you have brachytherapy may vary between hospitals. The general process is described below, but your treatment team can give you more specific information.

How brachytherapy works

In brachytherapy, sealed radioactive sources are placed inside the body, close to or inside the cancer. The sources produce gamma rays, which have the same effect on cancer as the x-rays used in EBRT, but act over a short distance only. It is a way of giving a high dose of radiation to the cancer with only a very low dose reaching surrounding tissues and organs.

The type of brachytherapy used depends on the type of cancer. It may include seeds (pellets), needles, wires or small mobile sources that move from a machine into the body through applicators (thin plastic tubes). Brachytherapy may be used alone or with EBRT.

Planning brachytherapy

The radiation oncologist will explain what treatment will involve and tell you whether you can have treatment during a day visit (outpatient) or will need a short stay in hospital (inpatient). You will have tests and scans to help your team decide where to place the radioactive sources and work out the correct dose to deliver to the cancer. These tests may include an ultrasound, CT scan and/or MRI scan.

The radiation oncologist will explain possible side effects and discuss any safety precautions. For some cancers, imaging tests, planning and treatment may happen in the same session.

What to expect at treatment sessions

Depending on the type of brachytherapy you are having, you may need to have a local anaesthetic to numb the area being treated, or a general anaesthetic so you will be unconscious for the treatment. The radiation sources will be positioned in your body, sometimes with the help of imaging scans (such as x-ray, ultrasound and CT) and computers.

You should not have any severe pain or feel ill during a course of brachytherapy. If the radioactive sources are being held in place by an applicator, you may feel some discomfort, but your doctor can prescribe medicine to help you relax and relieve any pain. Once the applicator is removed, you may be sore or sensitive in the treatment area.

After the treatment, you may have to limit physical and sexual activity and take some safety precautions for a period of time – your treatment team will advise you.

Dose rates

You may be told you are having high-dose-rate or low-dose-rate brachytherapy. Pulsed-dose-rate brachytherapy is not used often.

high-dose-rate (HDR) – Uses a single source that releases high doses of radiation in short sessions, each lasting a number of minutes. The source is removed at the end of each session.

low-dose-rate (LDR) – Uses multiple sources or seeds that release radiation over days, weeks or months. The sources may be temporary or permanent.

pulsed-dose-rate (PDR) – Uses a single source that releases radiation for a few minutes every hour over a number of days. The source is removed at the end of treatment

Types of brachytherapy

Depending on the type of cancer and your radiation oncologist’s recommendation, the radioactive sources may be placed in your body for a limited time or permanently.

Temporary brachytherapy

With temporary brachytherapy, you may have one or more treatment sessions to deliver the full dose of radiation. The radioactive source can be inserted using applicators such as thin plastic tubes (catheters) or cylinders. It can also be delivered using small discs called plaques. The source is removed at the end of each treatment session. The applicator may be removed at the same time or after the final session.

Temporary brachytherapy using applicators is mostly used for prostate cancer and gynaecological cancers (e.g. cervical and vaginal cancers). Radioactive plaques are used to treat some eye cancers.

Having temporary brachytherapy

High-dose-rate brachytherapy – This will be given for a few minutes at a time during several sessions. The radiation therapists will leave the room briefly during the treatment, but will be able to see and talk to you from another room. You may be able to have this treatment as an outpatient.

Low-dose-rate or pulsed-dose-rate brachytherapy – The radioactive sources will deliver radiation over 1–6 days. For these types of brachytherapy, you will stay in hospital for a few days and will be in a dedicated treatment room on your own. This room is close to the main hospital ward – you can use an intercom to talk with staff and visitors outside the room. If you have concerns about being alone, talk to the treatment team.

Safety precautions for temporary brachytherapy

While the radioactive source is in place, some radiation may pass outside your body. For this reason, hospitals take certain safety precautions to avoid exposing staff and visitors to radiation. Staff will explain any restrictions before you start brachytherapy treatment.

If you have temporary high-dose-rate brachytherapy, once the source is removed, you are not radioactive and there is no risk to other people. You won’t have to take any further precautions.

For low-dose-rate or pulsed-dose-rate brachytherapy, while the radiation source is in place precautions may include:

- hospital staff only coming into the room for short periods of time

- limiting visitors during treatment

- visitors sitting away from you

- avoiding contact with children under 16 and pregnant women.

Permanent brachytherapy

In permanent low-dose-rate brachytherapy, radioactive seeds about the size of a grain of rice are put inside special needles and implanted into the body while you are under general anaesthetic. The needles are removed, and the seeds are left in place to gradually decay.

As the seeds decay, they slowly release small amounts of radiation over weeks or months. They will eventually stop releasing radiation, but they will not be removed. Low-dose-rate brachytherapy is often used to treat early-stage prostate cancers.

Safety precautions for permanent brachytherapy

If you have permanent brachytherapy, you will be radioactive for a short time after the seeds are inserted. The radiation is usually not strong enough to be harmful to people around you, so it is safe to go home. However, you may need to avoid close contact with young children and pregnant women for a short time – your treatment team will advise you of any precautions to take. You will normally be able to return to your usual activities 1–2 days after the seeds are inserted.

"For the first few weeks after the seeds were implanted, I thought this is a doddle. Then suddenly, I started getting this really urgent need to urinate. That gave me a few weeks of disturbed sleep, but the urgency gradually eased off and I thought this is pretty good. Now after 3 years, there’s no sign of the cancer and I’ve had no long‑term side effects.” DEREK

Other types of internal radiation therapy

For some cancers, you may be referred to a nuclear medicine specialist to have another type of internal radiation therapy.

Radionuclide therapy – Also known as radioisotope therapy, this involves radioactive material being swallowed as a capsule or liquid, or given by injection. The material spreads throughout the body, but particularly targets cancer cells. It delivers high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells with minimal damage to normal tissues.

Different radionuclides are used to treat different cancers. The most common radionuclide therapy is radioactive iodine, which is swallowed as a capsule and used to treat certain types of thyroid cancer.

Other radionuclide therapies include:

- peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), used to treat neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) of the bowel, pancreas and lung

- lutetium prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) therapy, used to treat some advanced prostate cancers

- I-MIBG therapy, used to treat some types of NETs or neuroblastoma

- bone-seeking radioactive liquid, used to target cancer that has spread to the bone

- radioactive antibodies, used to treat lymphoma.

Radionuclide therapies may be available only in certain specialised treatment centres in each state and some may be available only on clinical trials or at a considerable out-of-pocket cost. Talk to your doctors for more information.

SIRT – This stands for selective internal radiation therapy. It is also known as radioembolisation. SIRT uses tiny radioactive beads to deliver high doses of radiation to the liver. The beads are injected into a thin tube called a catheter, which is inserted into the main artery that supplies blood to the liver.

Radiation from the beads damages the cancer cells and their blood supply. This means the cancer can’t get the nutrients it needs and it shrinks.

Managing side effects

Radiation therapy can treat many cancers, but it can also injure healthy cells at or near the treatment area. This can lead to side effects. Before recommending radiation therapy, the radiation oncologist will consider whether the likely benefits outweigh the possible side effects. To minimise side effects, a range of new techniques have made radiation therapy highly precise.

This section provides information and tips to help people manage some common side effects of radiation therapy. You are unlikely to have all of these side effects. You may have other side effects not discussed here or you may have symptoms unrelated to your treatment.

Preparing for side effects

Some people have many side effects, while others have very few or none. Side effects can vary even among people having the same type of radiation therapy to the same part of the body. Your treatment team can give you an idea of what to expect. Many things can affect the type and severity of side effects, including:

- the part of the body treated

- the type of radiation therapy

- the dose of radiation needed and the number of treatment sessions

- any other treatments you might be having and your general health.

Most side effects that occur during treatment are manageable. Before treatment begins, your radiation therapy team will discuss how to look after the treatment area, the side effects to watch out for or report, ways to manage them, and who to contact after hours if you need help.

While you are having treatment, let the radiation therapy team know at each treatment session about any side effects you have. To help manage side effects, the radiation oncologist may alter the treatment or arrange a break. They may not recommend these options if it would affect how well the treatment works.

Looking after yourself

It is important to maintain your general health. People who have diabetes need to manage their blood sugar levels during treatment and recovery – see your GP before treatment starts. Your treatment team will encourage you to be as active as possible during treatment. Research shows that exercise can help people manage the ongoing effects of radiation therapy, including fatigue.

Trying complementary therapies

Complementary therapies are used with conventional medical treatments. Therapies such as relaxation and mindful meditation can reduce anxiety and improve your mood.

Let your radiation oncologist know about any complementary therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or may make side effects worse. This includes over-the-counter and herbal medicines, vitamins and creams. You may also need to avoid massaging the treatment area.

How long side effects may last

Radiation therapy can cause side effects during and just after treatment. These are called short-term or acute effects. Most side effects are temporary and go away in time, usually within a few weeks of treatment finishing. But sometimes radiation therapy can cause long-term or late effects months or years down the track.

Short-term side effects

Side effects often build up slowly during treatment and it could be a few days or weeks before you notice anything. Often the side effects are worse at the end of treatment, or even 1–2 weeks afterwards, because it takes time for the healthy cells to recover from radiation.

Long-term or late side effects

Radiation therapy can also cause side effects that last for months or years after treatment. These long-term effects are usually mild, they may come and go, and they may not have any major impact on your daily life. Sometimes they may be more serious. Late side effects may go away or improve on their own, but some may be permanent and need to be treated or managed.

Other cancers – Very rarely, years after successful treatment, patients can develop a new, unrelated cancer in or near the area treated. The risk of this late effect is very low, but other factors, such as continuing to smoke or very rare genetic conditions, can increase this risk.

Effects on the heart – Radiation therapy to the chest, particularly when combined with chemotherapy, may lead to an increased risk of heart problems. Newer techniques have reduced the risk, however, talk to your doctor about your heart health. If you develop heart problems later in life, make sure you let your doctors know you had radiation therapy.

Fatigue

Fatigue is feeling very tired and lacking energy for day-to-day activities. It is the most common side effect of radiation therapy to any area of the body. During treatment, your body uses a lot of energy dealing with the effects of radiation on normal cells. Fatigue can also be caused by travelling to daily treatment sessions and other appointments.

Fatigue usually builds up slowly during treatment, particularly towards the end, and may last for some weeks or months after treatment finishes. Many people find that they cannot do as much as they normally would, but others are able to continue their usual activities.

How to manage fatigue

- Take regular short breaks.

- Plan activities for the time of day when you tend to feel more energetic.

- Ask family and friends for help (e.g. with shopping, housework and driving).

- Take a few weeks off work during or after treatment, reduce your hours, or work from home. Discuss your situation with your employer.

- Do some regular exercise, such as walking. This can boost your energy levels and make you feel less tired. Ask your treatment team about what type of exercise is suitable for you.

- Limit caffeinated drinks, such as cola, coffee and tea, if they affect your sleep or make you feel irritable.

- Avoid drinking alcohol.

- If you smoke, try to quit.

- Eat regular meals and have a balanced diet from the 5 food groups – fruit, vegetables and legumes, wholegrains, meat (or alternatives) and dairy (or alternatives).

Skin changes in the treatment area

Depending on the part of the body treated, the number of treatments and the radiation dose, EBRT may make skin in the treatment area dry, itchy and flaky. Your skin may change in colour (look red, sunburnt or tanned) and may feel painful if it peels. Skin changes often start 10–14 days after the first treatment. They often get worse during treatment, before improving in the weeks after treatment.

You may need dressings and creams to help the area heal, avoid infection and make you more comfortable. Pain medicine can help if the skin is very sore. Your treatment team will check your skin regularly. Let them know about skin changes, such as cracks or blisters, moist areas, rashes, infections, swelling or peeling.

Taking care of your skin

- Clean skin with warm water and a mild unscented soap. Gently pat skin dry with a soft towel.

- Ask your doctor or nurse what type of water‑based moisturiser to use. Avoid perfumed or scented products.

- Start moisturising from the first day of treatment. Apply moisturiser at least 2 hours before or after each session.

- Protect your skin outdoors. The sun can irritate skin changes and delay healing.

- Let temporary skin markings wear off by themselves. Don’t scrub your skin to remove them.

- Avoid using razors, hair dryers, hot water bottles, heat packs, wheat bags or icepacks on the area that has been treated.

- Wear loose, soft cotton clothing. Avoid tight-fitting items in the treatment area.

- Check with your doctor about swimming. Chlorine may worsen skin reactions for some people.

Hair loss in the treatment area

If you have hair in the area being treated, you may lose some or all of it during or just after radiation therapy. The hair will usually grow back a few months after treatment has finished, but it may be thinner or have a different texture. Hair loss may be permanent with higher doses of radiation therapy.

Hair will only fall out in the treatment area. Talk with your doctor before treatment starts about what hair loss to expect.

Ways to manage hair loss

- If you are having radiation therapy to your head or scalp area, think about cutting your hair short before treatment starts. Some people say this gives them a sense of control.

- If you are going to wear an immobilisation mask, talk to the treatment team before the planning scan about whether you need to remove your beard or cut your hair.

- Wear a wig, hairpiece or leave your head bare. Do whatever feels comfortable.

- Protect your scalp against sunburn and the cold with a hat, beanie, turban or scarf.

- If you plan to wear a wig, choose it before treatment starts so you can match it to your own hair colour and style. For more information about wig services, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

- Ask your hairdresser or barber how to style your hair. It may be thinner or curly when it was once straight, and the new growth may be patchy for a while.

- Contact the Look Good Feel Better program. It helps people manage the appearance-related side effects caused by cancer treatment.

Appetite loss and nausea

Some people may lose interest in food or find it difficult to eat well during radiation therapy. This can depend on the part of the body being treated. It is important to try to keep eating well so you can maintain your weight. Good nutrition will give you more strength, help you manage any side effects, and improve how you respond to treatment.

Radiation therapy near the abdomen, pelvic region or head – You may feel sick (nauseated), with or without vomiting, for several hours after each treatment. Your radiation oncologist may prescribe medicine (an antiemetic) to take at home before and after each session to prevent nausea. If you are finding nausea difficult to manage, talk to the radiation oncologist or nurse, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Radiation therapy to the head and neck area – Chewing or swallowing may be difficult or painful. Your sense of taste may also change if radiation therapy has affected the salivary glands or tastebuds. In some cases, taste changes may be permanent.

Getting help from a dietitian – If you are finding it difficult to eat well and get the nutrition you need, a dietitian can suggest changes to your diet, liquid supplements or a feeding tube. Dietitians work in all public and most private hospitals. You can ask your cancer care team for a referral to a dietitian to get advice on what to eat during treatment and recovery. To find an accredited practising dietitian in your area, visit Dietitians Australia.

"At first, I couldn’t think about eating without thinking about throwing up. Drinking ginger beer helped control the nausea.”

SIMON

How to manage appetite changes

Appetite loss

- Don’t wait to feel hungry. Eat small meals every 2–3 hours during the day. Setting an alarm to remind you to eat may be helpful.

- Try to eat extra on days when you have an appetite.

- If you don’t feel like eating solid foods, try nourishing fluids, such as smoothies made with milk or milk powder. Add yoghurt, fruit, and nut butters for extra kilojoules and protein.

- Do not use nutritional supplements or medicines to improve your appetite without your doctor’s advice. They could affect treatment.

- Cooking smells may put you off eating. It might help if someone else prepares your food, or you could reheat precooked meals.

- Try to do some light physical activity, such as walking. This may improve your appetite.

- Let your treatment team know if you are having trouble eating or if your weight has changed.

Nausea

- Try food and drinks with ginger or peppermint to help reduce nausea.

- Sip on water and other fluids throughout the day to prevent dehydration.

- Have a bland snack (e.g. dry biscuits, porridge, crackers or toast).

- Ask your doctor if you can try anti-nausea medicine. It’s important to take anti-nausea medicine as directed to help prevent nausea – don’t wait until you feel sick. Let the doctor

know if the medicine doesn’t help as they can offer you a different one to try. - Contact your treatment team if the nausea doesn’t ease after a few days, or if you have been vomiting for more than 24 hours.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Mouth and throat problems

Radiation therapy is often used to treat cancers in the mouth, throat, neck or upper chest region. Depending on the area treated, radiation therapy may affect your mouth and teeth. This can make eating and swallowing difficult, and change your sense of taste.

Taste and swallowing changes – You may have thick phlegm in your throat, or a lump-like feeling that makes it hard to swallow. Food may also taste different. Normal taste usually returns in time. Sometimes, swallowing may be affected for months after treatment. If this happens, talk to your doctor. They can refer you to a speech pathologist to help you manage any swallowing difficulties.

Dry mouth and other issues – After treatment, your mouth or throat may become dry and sore, and your voice may become hoarse. Radiation therapy can cause your salivary glands to make less saliva, which can contribute to a dry mouth (xerostomia). These effects will gradually get better after treatment finishes, but it may take several weeks or even months. In some cases, the effects may improve but not completely disappear. Dry mouth can make chewing, swallowing and talking difficult. A dry mouth can also make it harder to keep your teeth and mouth clean, which can increase the risk of tooth decay.

Teeth problems – If radiation therapy to the mouth dries up your saliva, this may increase the chance of tooth decay or other problems. You will need a thorough dental check-up and may need to have any decaying teeth removed before treatment starts. Your dentist can provide an oral health care plan with instructions on caring for your teeth and dealing with side effects such as mouth sores. You will need regular dental check-ups after treatment ends to prevent any problems in the future.

How to relieve mouth and throat problems

- Have a dental check-up before you start treatment. Ask for a referral to a dentist who specialises in the effect of radiation therapy on teeth.

- Keep your mouth moist by sucking on ice chips, mints and sipping cool drinks. Carry a water bottle with you.

- Ask your doctor, nurse or pharmacist for information about artificial saliva to moisten your mouth.

- Chew sugar-free gum to help the flow of saliva.

- If you have a dry mouth try using sauce or gravy to moisten foods. Have a drink with your meal to help wash food down, especially if you are eating dry foods such as nuts, toast or dry biscuits.

- Avoid smoking and drinking alcohol or caffeinated drinks. These things will irritate your mouth and make dryness worse.

- To manage taste changes, add more flavour to food (e.g. add lemon juice, herbs and spices to meat and vegetables, marinate foods).

- If you have mouth ulcers, you may need to limit spicy, salty or citrus foods, or foods that are very hot or cold.

- Ask your doctor for a referral to a speech pathologist. They can suggest ways to modify the texture of foods so they are easier to swallow.

- Ask a dietitian to suggest meals and snacks to try.

- Talk to your doctor if eating is uncomfortable or difficult. If you are in pain, ask them about pain medicine to help with chewing and swallowing. Eating soft foods or drinking liquids using a straw may help.

- Take care of your mouth. Ask your doctor or nurse what type of alcohol-free mouthwash to use and how often to use it. They may give you an easy recipe for a homemade mouthwash.

Download our fact sheet ‘Mouth Health and Cancer Treatment’

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Taste and Smell Changes’

Bowel changes

If you have radiation to the pelvic area, the radiation therapists may advise you to drink fluids before each treatment. This will expand your bladder and push the bowel away from the radiation.

Even with precautions, radiation therapy can irritate the lining of the bowel or stomach and affect the way the bowel works. These changes are usually temporary, but for some people they are permanent and can have a major impact on quality of life. It is important to talk to your treatment team if you are finding bowel issues difficult to manage.

Diarrhoea – This is when you have many loose, watery bowel motions. You may also have abdominal cramps, wind and pain. Towards the end of a course of radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvic area, you may need to go to the toilet more urgently and more often. Having diarrhoea can be tiring, so rest as much as possible and ask others for help. Diarrhoea can take some weeks to settle down after treatment is over.

Radiation proctitis – Radiation therapy to the pelvic area can irritate the lining of the rectum, causing inflammation and swelling known as radiation proctitis. Symptoms may include blood and mucus in bowel motions; discomfort opening the bowels; or the need to empty the bowels often, perhaps with little result. Ask your radiation oncologist about your risk of developing radiation proctitis. It is usually short term but may be ongoing in a small number of people.

Bowel blockage – Rarely, after radiation therapy to the pelvis, especially if you have had previous abdominal surgery, you may develop a bowel blockage. This can be serious. It is important to let you doctor and treatment team know if you have pain in the abdomen, vomiting and difficulty opening your bowels.

How to manage diarrhoea

- Ask your doctor about suitable medicines for diarrhoea. Take as directed.

- Check with your treatment team before taking any over-the-counter or home remedies – taking them with anti-diarrhoea medicines may cause side effects.

- Drinking peppermint tea may reduce abdominal or wind pain.

- Continue to eat and drink. This is important to avoid weight loss and to give your body the nutrients it needs.

- Do some gentle exercise, such as walking, to encourage healthy bowel movements. Check with your doctor about the amount and type of exercise that is right for you.

- Try limiting caffeine from drinks such as tea, coffee, cola and other soft drinks. These can

stimulate the bowel. - Drink plenty of liquids when you first notice symptoms. This helps to avoid dehydration and replaces fluids lost through diarrhoea. Try apple juice, weak tea, clear broth, sports drinks and electrolyte‑replacing fluids. Switch to soy milk or lactose-free milk for a period of time.

- Choose plain foods that are low in insoluble fibre (e.g. bananas, mashed potato, apple sauce, white rice or pasta, white bread, steamed white fish or chicken). Talk to your dietitian about what else you can eat.

- Avoid high-fibre, fatty or fried foods; pulses; garlic and onion; and rich sauces and gravies, as these can make diarrhoea worse.

- Reduce sugar-free or diet soft drinks and sweets that contain sorbitol, mannitol and xylitol as these can make diarrhoea worse.

- Contact your treatment team immediately if there is blood in your bowel motions or if you have more than 5–6 bowel movements in 24 hours.

The blood vessels in the bowel can become more fragile after radiation therapy. This may mean you see blood in your bowel motions, even months or years after treatment. Always let your doctor know if you notice new or unusual bleeding.

Bladder changes

Radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvic area can irritate the bladder or, more often, the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body).

Cystitis – You may have some stinging when you pass urine or feel you want to pass urine more often and more quickly. This is called cystitis. Symptoms usually ease within 3 months of finishing radiation therapy.

Urinary incontinence – Incontinence is when urine leaks from your bladder without your control. After radiation therapy, you may need to pass urine more often or feel as if you need to go in a hurry. You may leak a few drops of urine when you cough, sneeze, laugh or strain. Sometimes radiation can narrow the urethra, causing permanent incontinence.

Ways to manage bladder changes

Strengthening the pelvic floor muscles can help with bladder control. Ask your doctor for a referral to a continence nurse or physiotherapist, or visit the National Continence Helpline or call them on 1800 33 00 66.

Let your treatment team know if you have bladder or urinary problems, as they will be able to suggest strategies and may recommend medicines. To help manage these side effects, drink plenty of fluids, limit strong coffee and tea, and avoid drinking alcohol.

The blood vessels in the bladder can become more fragile after radiation therapy. This may mean you see blood in your urine, even months or years after treatment. Always let your doctor know if you notice new or unusual bleeding.

Lymphoedema

When lymph fluid builds up in the tissues under the skin, it can cause swelling (oedema). This is known as lymphoedema. It can happen if lymph nodes have been removed during surgery or damaged by the cancer, infection, injury or radiation therapy. Lymphoedema usually occurs in an arm or leg, but can also affect other parts of the body. The main signs of lymphoedema include swelling, aching or a feeling of tightness, which may come and go.

People who have had surgery followed by radiation therapy are more at risk. Lymphoedema or swelling is sometimes just a temporary effect of radiation therapy, but it can be ongoing. It can also be a late effect, appearing months or even years after treatment.

Ways to manage lymphoedema

Lymphoedema is easier to manage if the condition is treated early. Treatment will aim to improve the flow of lymph fluid. It is important to keep active, avoid pressure, injury or infection to the affected part of your body, and see your doctor if you have any signs of lymphoedema.

Specialist physiotherapists (called lymphoedema practitioners) can help you to reduce your risk of lymphoedema or show you ways to manage lymphoedema if you have developed it. A personalised treatment plan may include exercises, skin care, lymphatic drainage massage and compression garments, if needed.

Some hospitals have lymphoedema practitioners, and there are also practitioners in outpatient clinics and private practice. To find a practitioner, visit the Australasian Lymphology Association.

Sexuality, intimacy and fertility issues

Radiation therapy can affect your sexuality and fertility in emotional and physical ways. These changes are common. Some changes may be temporary, while others may be permanent.

Changes in sexuality

You may notice a lack of interest in sex or a loss of desire (libido), or you may feel too tired or unwell to want to be intimate. You may feel less sexually attractive to your partner because of changes to your body. All of these feelings are quite common. Although it is usually safe to have sexual intercourse, it may be uncomfortable, depending on where the radiation therapy is given. Talk to your doctor about ways to manage any side effects that change your sex life.

Using contraception

A woman’s eggs (ova) and a man’s sperm can be affected by very small amounts of radiation when having radiation therapy to any part of the body. Depending on the type of radiation therapy you have, your doctor may talk to you about using a barrier method of contraception (such as a condom or female condom). If pregnancy is possible, your doctor will advise you to avoid pregnancy by using contraception during radiation therapy and for at least 6 months after you have finished treatment. Talk to your doctor as soon as possible if pregnancy occurs.

I didn’t realise the radiation would affect my sexuality until it happened. I don’t think anyone can tell you what the pain, discomfort and exhaustion will do to you.” DONNA

Changes in fertility

The risk of infertility (difficulty getting pregnant or conceiving a child) will depend on the area treated, the dose of radiation and the number of treatment sessions. If you are treated with both radiation therapy and chemotherapy (chemoradiation), the risk of permanent infertility is higher.

Radiation therapy to the pelvic area, abdomen and sexual organs can affect your fertility, and this can be temporary or permanent. Radiation therapy to the brain can damage the pituitary gland, which controls the hormones the body needs to produce eggs or sperm.

If infertility is a potential side effect, your radiation oncologist will discuss it with you before treatment starts. Let them know if you think you may want to have children in the future. Ask what can be done to reduce the chance of problems and whether you should see a fertility specialist beforehand.

Sometimes, however, it is not possible to properly treat the cancer and maintain fertility. Many people feel a sense of loss when they learn they may no longer be able to have children. If you have a partner, talk to them about your feelings. Talking to a counsellor may also help.

Effects of radiation therapy on sex and fertility

Radiation therapy to the abdomen, pelvis and reproductive organs can affect your sexual function and ability to have children.

Changes to the vagina

- Radiation therapy to the vulva or vagina may cause inflammation, making intercourse painful. This usually improves in the weeks after treatment ends. Your treatment team will recommend creams and pain relief to use until the skin heals.

- Talk to your doctor about using vaginal moisturisers, which may help with discomfort. In some cases, oestrogen creams are prescribed.

- The vagina may become shorter and narrower (vaginal stenosis), making intercourse difficult or painful. Having regular intercourse or using vaginal dilators after treatment ends can help keep the vagina open. Wait until any soreness or inflammation has settled before you start using a dilator or having sex. This is usually 2–6 weeks after your last session of radiation therapy. Using a dilator can be challenging. Your doctor, nurse or a physiotherapist can provide instructions.

- If sexual penetration is painful or difficult, explore other ways to orgasm or climax.

Menopause

- Radiation therapy to the pelvic area or abdomen usually stops the ovaries producing female hormones, which leads to early menopause.

- Your periods will stop and you may have menopausal symptoms. These may include hot flushes, dry skin, vaginal dryness, mood swings, trouble sleeping (insomnia) and tiredness.

- If vaginal dryness is a problem, take more time before and during sex to become aroused. Using lubrication may also make intercourse more comfortable.

- Discuss changes to your libido with your partner so they understand how you’re feeling.

- Ask your GP to arrange a bone density test to check for osteoporosis or osteopenia, which can develop after menopause.

- Talk to your doctor about ways to manage the symptoms of menopause. If you need support resuming sexual activity, ask your doctor for a referral to a sex therapist or psychologist.

Sperm and erection problems

- Radiation therapy to the pelvic area or near the testicles may temporarily affect how much sperm you make. You may notice that you feel the sensation of orgasm but ejaculate little or no semen. This is known as dry orgasm. It may be temporary or permanent.

- Depending on the dose and the area of the pelvis treated, you may have trouble getting and keeping an erection firm enough for intercourse. This is called erectile dysfunction or impotence. Sometimes impotence may be permanent.

- In some cases, you may experience pain when ejaculating. The pain usually eases over a few months but may be permanent.

- Talk to your treatment team if erection problems are ongoing and causing you distress. They can suggest ways to keep your penis erect, such as prescription medicines, penile implants or vacuum erection devices.

Infertility

- Sometimes, changes to sperm production and ability to have erections are permanent. This may cause infertility. If you want to have a child, you may choose to store sperm before treatment starts. Your partner can use this sperm to conceive through artificial insemination or in-vitro fertilisation in the future.

- If radiation therapy causes menopause, you will no longer be able to become pregnant. If you wish to have children in the future, talk to your radiation oncologist before treatment starts about ways to preserve your fertility, such as storing eggs or embryos or freezing ovarian tissue.

- If your ovaries don’t need to be treated, one or both of the ovaries may be surgically moved higher in the abdomen and away from the field of radiation. This is called ovarian transposition or relocation (oophoropexy). It may lower the amount of radiation your ovaries receive and it may help them keep working properly.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of radiation therapy. It may be some time before you know whether the treatment has controlled the cancer. Radiation therapy usually does not have an immediate effect, and it could take days, weeks or months to see any change in the cancer. The cancer cells may keep dying, and side effects can continue, for weeks or months after the end of treatment.

After radiation therapy has finished, your treatment team will tell you how to look after the treatment area and recommend ways to manage side effects. They will also advise who to call if you have any concerns.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment finishes, you will have regular check-ups to see how the cancer has responded to treatment. This may be in person at the treatment centre or using telehealth. You may see the radiation oncologist, your GP or another specialist, depending on where you live and what the treatment team recommends. Check-ups will become less frequent over time.

You may also have follow-up appointments with nurses from your treatment centre to help manage any ongoing symptoms, as well as regular check-ups with other specialists who have been involved in your treatment.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people find that they think more about the cancer and may feel anxious. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

Contact your treatment team if you have any health problems between follow-up appointments. Many of the long-term or late effects of radiation therapy can be managed better if found early.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling service. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.