The information provided here focuses on when a parent has cancer, but much of the discussion will be relevant for anyone who needs to explain a cancer diagnosis to children or teenagers – for example, when a child’s sibling or friend has cancer, when their grandparent or another significant adult has cancer, or when the child has cancer.

Different sections offer tips on talking with children throughout all stages of cancer, from sharing the news about a cancer diagnosis to adjusting to life after treatment or speaking about end of life.

This information includes quotes and stories from people who have been affected by cancer, along with examples of what a parent or carer might say. These are just ideas; you will need to adapt what you say to suit your children’s ages and their individual personalities. You know your children best and can judge their ability to understand things.

Talking about cancer

Talking with kids about cancer can feel overwhelming. Your first reaction may be to keep the news of the diagnosis from children or to delay telling them. Or you may feel an urgent need to tell them straightaway. Even though it can be difficult, research shows that being open helps children cope with the cancer diagnosis of someone close to them.

This section explores some of the issues you may like to consider as you approach these conversations.

Why talk to kids about cancer?

When someone is diagnosed with cancer, adults are sometimes hesitant to discuss the situation with children. Parents and other adults can feel overwhelmed by their own anxiety and fear, and their first reaction may be to protect children from those same strong emotions.

They may be concerned about their children’s reactions or worry the diagnosis will disrupt their children’s school performance or friendships. However, there are many reasons why a straightforward and open discussion can help children.

You are the expert

As parents and carers, you are the experts on your children and what works for them. To help you discuss the difficult subject of cancer with children, this information offers evidence-based, practical strategies that can build upon your existing strengths and knowledge.

Sometimes it may take a few attempts before you find an approach that suits your family. Use your understanding of your children’s individual personalities and needs to guide you.

Secrecy can make things worse

Children who are told about the illness of someone important to them tend to cope better than children who are kept in the dark. Trying to keep the diagnosis secret can be difficult; it can add to your stress and can be confusing for children. For example, you may need to change your family’s daily routine to attend specialist appointments and your children may not understand why.

You can’t fool kids

Children are observant. No matter how hard you try to hide a cancer diagnosis, most children will suspect something is wrong. Even if it’s an aunt or grandparent who has cancer, rather than a parent, kids will usually pick up on any stress this causes in the family.

They may notice changes at home, such as your sadness, whispered conversations and closed doors. Or they may see that their family member looks different or cannot do certain things. These signs may be more obvious to older children and teenagers, but even young children can pick up on change. They will work out that a secret exists.

Not knowing the reason for the secret may leave them feeling powerless or left out of family matters. They may also feel that they have done something that has caused this change in the family, or imagine that the situation is worse than it actually is.

Being open can build trust with your child

Children can feel hurt if they suspect or discover they have not been told something important that affects their family. Sharing information shows you trust and value them, which can boost their self-esteem and ease their concerns. The diagnosis may also be a chance for children to learn from their parents how to deal with complex feelings. Together, you can all find ways to cope with difficult situations (resilience).

How children hear about a diagnosis is important

Ideally, children should hear about a cancer diagnosis from their parents, guardian or a trusted family friend, particularly if it is the parent, a relative or close friend who has cancer.

If you tell friends and relatives about cancer in the family, but you don’t tell your children, there is a chance your kids will learn about the cancer from someone else or overhear a conversation. Children often listen to adult conversations even when it seems like they are busy with their own activity and not paying attention.

Overhearing the news can make your children feel upset and confused. They may think they are not important enough to be included in family discussions or that the topic is too terrible for you to talk about.

Children may make up their own explanation to fill in the gaps in their understanding. They may feel afraid to ask questions and worry in silence. Teenagers, and even younger children, may pick up on a few key words and search the internet for answers, which can lead them to

unreliable websites. They may spread incorrect information to other children in the family.

Kids can cope

When a family is affected by cancer, it can be an unsettling time for kids. You may wonder how they will get through it, but with age-appropriate information and good support, most children can cope with this difficult situation.

Kids have surprising abilities to respond to life’s challenges. They learn about emotions and how to express them by watching others – especially their parents. Parents can role model how to recognise, talk about and manage a range of emotions. For example, you might say: “I’m feeling sad that Grandma is sick and I think I need to go for a walk.”

It’s okay to explain to your child that what you are telling them is upsetting and it’s natural to have strong feelings. We can’t stop kids from feeling sad, but if we share our feelings and give them information about what’s happening, we can support them in their sadness.

Children need a chance to talk

Talking to your children about cancer gives them the chance to ask questions. Encourage your kids to share their thoughts and feelings, but don’t be surprised if they don’t want to talk when you do, and don’t push your kids if they would prefer not to talk. Younger children may like to draw a picture, while older children may find it helpful to keep a journal to write down questions or thoughts as they come up.

Sometimes kids, particularly teenagers, may feel guilty about burdening a sick parent with their worries or taking up a healthy parent’s time. Reassure them that their concerns are not a burden. They may also like to speak to an adult who is not their parent (e.g. a grandparent, an aunt or an uncle) or perhaps another trusted person in their lives, such as a school teacher, counsellor or coach.

Sooner or later, they were going to find out. Why not tell them straightaway? I tell them frankly what is happening. I think they find it much easier to cope because they are ready for things.” Susie, Mother of three children aged 12, 13 and 16

When you can’t talk about cancer

Some parents don’t want to tell their children about the diagnosis at all and try to keep it secret. People have their own reasons for not sharing the diagnosis with their children, including cultural beliefs or an earlier death of a relative from cancer. Sometimes you may want to wait to find out more about the diagnosis before telling your kids.

If you want to share the diagnosis with your children but your fear of saying or doing the wrong thing is keeping you from having this difficult conversation, it may be helpful to talk with a psychologist or social worker. They can help you develop a strategy. Keep in mind that talking about cancer will change over time. Some discussions may become easier, others may become more challenging.

Cancer in different cultures

There are a wide range of beliefs and ideas about cancer. People from some cultures believe that cancer is caused by bad luck, that it is contagious or always fatal. Others may believe that the cancer has been sent to test them. It is important to respect different ways of coping with a cancer diagnosis.

You may be reading this information because you work with children who have been affected by a cancer diagnosis. Before talking to someone else’s child about cancer, it’s essential that you understand and respect the wishes of the parents.

If a family wants to keep a diagnosis private, organisations such as Cancer Council 13 11 20,

Canteen, Camp Quality or Redkite may be able to suggest ways for children and other family members to discuss their feelings and concerns in a confidential setting.

Key points: Talking about cancer

- Start with questions to check what your children know about cancer and if they have any misconceptions.

- Offer basic information and provide more details if they ask.

- Practise your response to potential questions before talking to kids.

- Give yourself time to answer a question; it’s fine to say, “That’s a great question, I need to think about how to answer that”.

- Explain that the cancer is not their fault and they can’t “catch it”.

- Assure them they will always be looked after, even if you can’t always do it yourself.

- Ask questions and listen to your children so you know how they really feel.

- Share your own feelings to show kids that it is okay to feel strong emotions about the situation.

- Continue daily routines as much as you can. Talk about your children’s own activities as well, and let them know that it’s still okay to have fun.

Below we explore how children of different ages may understand a cancer diagnosis.

Key points include:

- Children may react in different ways. They may feel angry, sad or guilty. Physical reactions can include bedwetting or a change in appetite or in sleeping patterns.

- Teenagers may find it hard to talk to you or show you how they feel.

How children understand cancer

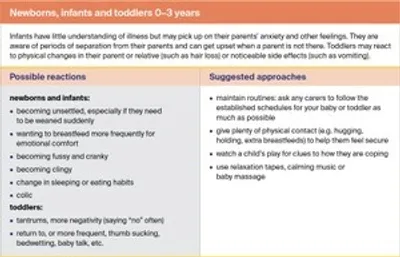

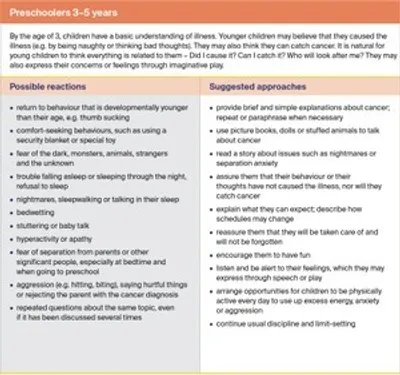

Children’s understanding of illness and their reactions to news of a cancer diagnosis will vary depending on their age, temperament and family experiences. You may find that siblings, even of similar ages, respond differently. These tables give an overview of children’s possible reactions at different ages, which might help you work out how best to support them.

As children grow up, their understanding of the world will also develop. You may need to check in with them to see if they need more information about the cancer. Some children’s understanding of cancer may be set at the age at which they were first told. As they mature, they may become ready for more in-depth conversations.

Newborns, infants and toddlers 0-3 years

Preschoolers 3–5 years

Primary school children 5–12 years

Teenagers 12–18 years

Talking about the diagnosis

When you first learn of a cancer diagnosis, you may feel shocked and overwhelmed. Among the many decisions you need to make will be when, where and how to talk to the children and young people in your life. Try to think of this as a series of conversations that evolve over time, rather than a one-off discussion. However you decide to approach these conversations, try to be open and leave kids with a feeling of realistic hope.

When should I tell my children?

It’s common to feel unsure about the best time to tell your children; often there is no right time. You may wonder if you should tell them soon after you’ve been told yourself or wait until you have more details about test results and treatment.

Although it is tempting to delay talking to your kids, try to tell them as soon as you feel able. Keeping the diagnosis a secret can be stressful, and your children will probably sense that something is wrong.

It’s also a good idea to tell children if:

- you think they may have overheard a conversation

- they are scared by adults crying

- they are shocked or confused by physical or emotional changes in the person who has cancer, especially if the person has symptoms such as frequent vomiting, weight loss, hair loss, or is admitted to hospital for immediate treatment

- you notice changes in their behaviour.

It may be hard to know how much information to share, particularly if you are waiting on test results. Your children don’t need to hear everything all at once. If you don’t know what treatment is needed, just say so – but also assure your children that as soon as you have more

information, you will tell them. For example, “Dad is in hospital having tests. We’re not sure what’s wrong, but we’ll tell you as soon as we know.”

Let children know it’s okay to have questions at different times, such as during treatment, and to talk about how they feel at any time.

Where should I tell my children?

Many people find that bringing up the topic while doing something else – like walking the dog or washing dishes – can help reduce the tension. This approach may be less intimidating than sitting down for a formal discussion, particularly if this is unusual for your family.

Try to find a time when you won’t be interrupted or need to rush off without answering all your children’s questions. Talking to kids before bedtime, school or an important event may not be a good idea. Ideally, you should tell them at a time and in a place where they feel able to listen and take in the news. For example, you may have the discussion on a weekend, so kids have the time to process the information.

It’s important that children are in a place where they feel safe so they feel comfortable to express emotions such as sadness or anger.

Should I tell them together?

If you have more than one child, you may wonder whether you should tell them individually or together. This will depend on the ages and temperaments of your children. You may need to use different language because of their ages. If you decide to tell them separately, try to tell them on the same day. Asking older children to keep the diagnosis a secret from younger siblings can add to their stress.

Who should tell my children?

In most cases, it is easier if the information comes from someone who is close to your children. Ideally, that will be the parent who has cancer, with the support of a partner or other close family member. Families can use language their kids understand and reflect on shared experiences in explaining the cancer diagnosis. This can help young people to understand the situation.

However, this is not always possible. Another adult close to your children, such as a grandparent, aunt, uncle or friend, may be able to tell them or be present when you tell them. This may be particularly important if you’re a single parent. You may decide to share the news with the support of a member of your health care team, such as your general practitioner (GP) or hospital social worker.

How can I prepare?

Parents often doubt their ability to find the right words and to answer the questions their children may ask. It’s not a matter of “getting it right”, rather it’s doing the best that you can at a challenging time. Take the time to plan what you’ll say. Role-playing the conversation with your partner, friend, relative, counsellor, or hospital social worker can help.

You may find it helpful to say certain phrases out loud before talking to your children. For example, you might practise saying “I have cancer” or “Grandma has cancer”. This means you’ve spoken the words and perhaps dealt with some of the anxiety attached to those words before you talk with your kids. You can also practise the conversation in front of a mirror. This helps set the words in your mind.

Even if you practise what to say and you think you know how your kids will respond, be prepared for questions and a wide range of reactions.

Before talking to your children, think about how the conversation might end. You could organise an activity, such as playing a game or going to the park, to help your children settle again.

Older children may prefer some time alone, or you may suggest watching a TV show or movie together. Let your kids know that they can talk to you any time they have questions or concerns.

What do children need to know?

The following is a guide to what to cover in your initial conversation about cancer.

Tell them the basics in words they can understand

You can share the news with a few short sentences explaining what you know so far and what is likely to happen next. Be clear about the name of the cancer, the part of the body affected and how the cancer will be treated.

To help explain cancer terms, you can:

- use a glossary

- get hints from websites

- read books about cancer written for children

- download Camp Quality’s Kids’ Guide to Cancer app from the App Store (Apple devices) or Google Play (Android devices). It provides information about cancer for kids aged up to 15 years.

Once you have explained the basics, ask your kids what else they want to know, and only answer questions that they ask. Don’t assume children will have the same concerns as you; you can give them more details later if needed.

For younger children, accept that they may ask the same question several times. Each time you answer, they will absorb a little more information. Older children may be distant and quiet while they process what you’ve told them.

Find out what they already know

Ask your children what they know about cancer and clear up any misinformation or myths (e.g. they might think that they can catch cancer or that everyone dies from cancer). Children get information from various sources, such as school and social media, and they may have their own ideas of what having cancer means. Parents can guide their children towards accurate online information.

It’s okay to say “I don’t know”

If you don’t know the answer to a question, it’s fine to say so. Tell your children that you’ll try to find out the answer from the doctor and let them know as soon as possible. Make sure you follow this through.

Tell them what to expect

Your children are likely to want to know what treatment will mean for their day-to-day lives. If you are in hospital, who will drop them to school, make them dinner, take them to after-school activities? Reassure them that there will be a plan and you will let them know what it is.

Ask them if they want to tell anyone

Your children may want to tell their close friends, their teacher, the whole class – or nobody. Explain that it’s helpful to share the diagnosis with a few key people, such as their main teacher and the school principal, as well as other important people in their life, such as a music tutor or sports coach. Discuss ways to approach these conversations.

Offering realistic hope

Tell kids that although cancer can be serious and going through treatment can be challenging, most people get better. Explain that with the help of the doctors and treatment teams, you (or the person with cancer) will be doing everything possible to get well.

Show your love and emotion

Tell your children that you love them. You may show your love by hugging them, comforting them, or other ways of making them feel valuable depending on your family and culture.

Some parents worry about crying in front of their children. It can be helpful for kids to know that strong feelings such as anger and sadness are normal and expressing them can make people feel better. Being open with each other about feelings can help your children cope.

"After Dad told us, the 6 of us sat around crying and hugging one another. Despite the sadness of the occasion, we actually had a pleasant dinner with lots of laughter. Our lives changed from that day.” Lily, aged 17

Coping with kids’ reactions

It’s natural for children and young people to have lots of different reactions to a cancer diagnosis. Talking with them about their reaction gives you a chance to discuss ways of managing how they’re feeling.

Crying

If your children cry, let them know it’s a natural reaction. Holding them will help some children feel secure. Let them know that they don’t have to “be strong”, and that feeling sad after a cancer diagnosis is common.

Fear

Some children will worry endlessly. Ask them what is their biggest worry. It can be hurtful if they start to avoid or ignore you. Explain that you are still the same person, despite any changes in how you look or behave.

Children may also worry that they’re going to be abandoned if something happens to the sick parent. Give your child a chance to talk about their fears and reassure them that they will always be cared for.

Anger

It is natural for children and young people to feel angry about the diagnosis as it means their lives could be disrupted.

Younger children may be annoyed if they have to miss a party or are asked to play quietly. Older children may seem angry and uncooperative if asked to help out more. Both may be disappointed or upset if a planned holiday has to be postponed or cancelled.

No reaction

Sometimes children will appear not to have heard the news or do not react. You may be confused or hurt by this, especially if it took some planning and courage to talk to your children about the diagnosis.

A lack of reaction isn’t unusual – often the children are protecting themselves and need some time to process the information. Or they may want to protect you from seeing how they are feeling. Remind them that they can talk to you or another trusted adult about it anytime.

It is likely that you will have several conversations about the diagnosis as your children’s understanding grows and other questions arise. Sometimes, despite your efforts to support your children, they may struggle with the impact cancer is having on their family. This is quite common and does not necessarily mean things have gone badly.

If your child is diagnosed

Families often describe the days and weeks after their child’s cancer diagnosis as overwhelming. Among the many confronting decisions they face is how to talk to the child about the illness.

Although the focus of this information is children affected by someone else’s diagnosis, much of the advice will still be relevant. Children with cancer tend to feel more secure when the adults around them are open – hiding the truth to protect a child may lead to greater anxiety.

How much information you share with your child will depend on their age and maturity. Keep your initial explanations simple and take your cue from your child as to whether they want to know more. The first conversation will be followed by many others, so you will have the

opportunity to give more detail as the need arises.

Someone from the paediatric oncology team will be able to provide guidance and assist you with these discussions. For younger children, some hospitals have therapists (may be called child life therapists) who teach children strategies to manage their illness and can help you explain the diagnosis and treatment. If you have an older child with cancer, get in touch with one of the Youth Cancer Services. These hospital-based services offer specialised treatment and support to people aged 15–25.

Children and teenagers will respond to their cancer diagnosis in different ways. Fear, anger or sadness are all common reactions. Let your child know that it’s normal to have a lot of different feelings and it’s okay to express these emotions. You can also talk to them about finding ways to cope with these challenging feelings.

Remember that your child’s hospital team is there to support the family as well. The social worker can let you know what support services are available, particularly if you need to travel long distances for treatment.

Some organisations have developed resources for parents of children diagnosed with cancer, including:

As much as possible, include your child in discussions about their treatment, and encourage them to ask questions. Older children and teenagers may want to seek out information themselves. You can point them to reliable organisations such as Camp Quality, Canteen and Redkite.

When a sibling has cancer

The siblings of children with cancer sometimes feel forgotten in the midst of a diagnosis. Parental attention is suddenly shifted, and daily routines, family roles and family responsibilities can change for a while.

Along with feelings of sadness, fear and anxiety, siblings may struggle with more complex emotions such as guilt, jealousy, resentment and anger. With so much focus on their brother or sister, they may feel that their needs do not deserve to be met and they have no right to complain.

For many children and teenagers, fitting in with their peers is very important. This means they may feel self-conscious about their family being different from others. Some may be reluctant to tell their friends and teachers about the situation at home. If cancer changes how their brother or sister looks, they may feel embarrassed and shy away from being seen with their sibling.

You can help your children adjust to the changes in your family by talking openly. Your kids may also be reassured to know the following:

It’s not their fault – Check that siblings realise that they did not cause their brother or sister’s cancer – even if they had been fighting with them or thinking mean thoughts about them.

What they can do – Explain that they can help support their brother or sister, and let them think about how they would like to do that. The sibling relationship is still important, so try to offer plenty of opportunities to maintain it. This may involve regular visits to the hospital and/or regular contact via texting, email or social media.

It’s okay to have fun – Although the child with cancer has to have a lot of attention, the needs of their siblings matter too. As far as possible, siblings should keep doing their own activities and have time for fun.

It’s okay to be cross – Most siblings argue at times, and it’s natural to be annoyed with a sibling who has cancer too. Being overprotective of a child with cancer can be harmful to them and their siblings.

They are loved – Explain to siblings that you may need to spend a lot of time and energy focused on the child with cancer, but this is out of necessity rather than feeling any less love for your other children.

They will always be looked after – Let your children know that you will make sure someone is always there to look after them.

When another child has cancer

In most cases, children will first learn about cancer when an adult in their life has been affected (e.g. a grandparent, aunt or teacher). So it can be confusing and frightening for children if a young friend or cousin is diagnosed with cancer.

Causes of cancer – Let your child know that childhood cancers are not lifestyle-related (e.g. caused by sun exposure or smoking), nor does a child get cancer because of naughty behaviour or a minor accident like a bump on the head. There’s nothing anyone did to cause the cancer.

It’s not contagious – Children need to feel safe around the child with cancer. Tell them that cancer can’t be passed on to other people. If the sick child is in isolation, this is to protect the child from infection, not to protect everyone else from the cancer.

Most children get better – Like adults, children may worry that cancer means their friend will die. Reassure children that although cancer is a serious, life-threatening disease, the overall survival rate for children is now almost 85%. This can vary depending on the diagnosis, but most children will survive cancer.

Expect change – Explain that things will change for the friend. They may feel too tired to play or may be away from school a lot. They may have physical changes (e.g. have hair loss or need to use a wheelchair).

Encourage your child to focus on what hasn’t changed – their friend’s personality and their friendship.

Visit the hospital if possible – It can be confusing for your child if the person with cancer disappears from their life after diagnosis. They may imagine the worst. It may be helpful to take your child to visit their friend in hospital, but first check with the friend’s parents and with the hospital to be sure visitors are allowed. Before the visit, let your child know that it’s natural to wonder how to act and what to say. The more time they spend with their friend, the more they’ll relax.

Keep in touch – If a hospital visit is not possible, there are other ways for your child to maintain the relationship with their friend. Younger children might like to make a card or a decoration for the hospital room, or you could organise time for a video call. Older children may prefer to communicate by phone or social media.

Encourage expression of feelings – Let your child know that it’s okay to have lots of different emotions and that you have them too.

Answering key questions

Q: What is cancer?

You may tell younger children: “Cancer is a disease that happens when bad cells stop the good cells from doing their job. These bad cells can grow into a lump and can spread to other parts of the body.”

For older children and teenagers, you may say: “Cancer is the name for more than 200 diseases in which abnormal cells grow and rapidly divide. These cells usually develop into a lump called a tumour or they may spread through the blood. Cancer may spread to other parts of the body.”

Q: Are you going to die?

This is the question that most parents fear, but often it doesn’t mean what you think. For example, younger children may really mean “Who is going to look after me?” Older children may be wondering, “Can we still go away during the school holidays?”

Try to explore the question by asking, “Do you have something in particular you’re worried about?” or “What were you thinking about?” You can explain that the treatment you are receiving is the result of many years of research and that treatments are improving all the time. If your child knows someone who has died of cancer, let them know that there are many different types of cancer and everyone responds differently.

Children and teenagers often have many questions about death and dying. Cancer commonly prompts them to reflect on their own life and the lives of those they care about.

“We don’t expect that to happen, but I will probably be sick for a while. I am doing everything I can to be well. Sometimes it makes me sad, and I wonder if you get sad too.”

Q: Was it my fault?

Some children may ask you directly if they caused the cancer, while others worry in silence, so it’s best to discuss the issue.

“It’s no-one’s fault I have cancer. Scientists don’t know exactly why some people get cancer, but they do know that it isn’t anything you did or said that made me sick.”

“You did not cause this cancer. There is nothing you could have said or done that would cause someone to have this illness.”

Q: Can I catch cancer?

A common misconception for many children (and some adults) is that cancer can spread from person to person (is contagious). This belief may be reinforced because when patients have chemotherapy they need to avoid contact with people who are sick. This is to protect the person with cancer from picking up infections, not to protect everyone else.

“You can’t catch cancer like you can catch a cold by being around someone who has it, so it’s okay to hug or kiss me even though I’m sick.”

“Cancer can spread through the body of a person with cancer, but it can’t spread to another person.”

Q: Who will look after me?

When family routines change, it’s important for children to know how it will affect their lives: who will look after them, who will pick them up from school, and how roles will change. Try to give them as much detail as possible about changes so they know what to expect. For older children, it’s helpful to ask them what arrangements they’d prefer.

“We will try to keep things as normal as possible, but sometimes I may have to ask Dad/Mum/Grandpa to help out.”

Q: Do I have to tell other people about it?

Your children may not know who to tell about the cancer or what to say. They may not want to say anything at all. It’s a good idea to ask how they feel about talking to others.

If you’re planning to inform teachers, the school counsellor or principal, talk to your kids first. Teenagers and even younger children may be reluctant for the school to know, so explain the benefits of telling the school and then chat about the best way to approach the discussion. Ask if your teenagers want to be involved in these discussions.

“You can tell your friends if you want to, but you don’t have to. People we know may talk about the diagnosis, so your friends might hear even if you don’t tell them. Many people find it helps to talk about the things that are on their mind.”

“Do you worry about how your friends will react or treat you?”

“I need to let your teachers know so they understand what’s happening at home at the moment. We can talk about who to tell and how much we should say.”

“Sometimes people talk about illness but they don’t know the full story. If the kids at school are talking about the cancer, let me know so we can discuss any things that they have got wrong.”

Q: Is there anything I can do to help?

Answering this question can be a delicate balance. Letting kids know that they can help may make them feel useful, but it’s important that they don’t feel overwhelmed with responsibility.

Some parents may feel hurt if their children don’t ask how they can help, but it’s common for children not to think to offer.

“Yes, there are lots of things you can do to help. We will work out what those things can be, and what will make things easier for everyone. Is there something in particular you would like to do?”

“Some help around the house would be good, but it’s important that you keep up with your schoolwork and you have some time for fun and for seeing your friends.”

What words should I use?

It’s often hard to find the words to start or continue a conversation. The suggestions below may help you work out what you want to say. Although these are grouped by age, you may find that the ideas in a younger or older age bracket work for your child.

About cancer

Infants, toddlers and preschoolers

“Mummy is sick and needs to go to hospital to get better. You can visit her soon.”

“I have an illness called cancer. The doctor is giving me medicine to help me get better. The medicine might make me feel sick or tired some days, but I might feel fine on other days.”

Younger children

“You know that Mum has been sick a lot lately. The doctors told us today that the tests show she has cancer. The good news is that she has an excellent chance of getting better.”

“Do you know what cancer is? Cancer is a disease of the body that can be in different places for different people.”

Older children and teenagers

“The doctors say Dad has a problem in his blood – it’s an illness called Hodgkin lymphoma. That’s why he’s been very tired lately. Dad will have treatment to help him get better.”

“Lots of people get cancer; we don’t usually know why. Most people get better and we expect I will get better too.”

To check knowledge of cancer

Infants, toddlers and preschoolers

“How do you think people get cancer?”

“Sometimes children worry that they thought or did something to cause cancer. No-one can make people get cancer, and we can’t wish it away either.”

“We can still have lots of kisses and hugs – you cannot catch cancer from me.”

Younger children

“We can still have lots of kisses and cuddles – you cannot catch cancer from me or from anyone who has it.”

“Even though your friends at school might say that cancer is really bad and I will get very sick, they don’t know everything about this cancer. I will tell you what I know about my cancer.”

Older children and teenagers

“There are many types of cancer and they’re all treated differently. Even though Uncle Bob had cancer, it might not be the same for me.”

“The doctor doesn’t know why I got cancer. It doesn’t mean that you’ll get cancer too. It’s not contagious (you can’t catch it) and the cancer I have doesn’t run in families.”

To explain changes and offer assurance

Infants, toddlers and preschoolers

“Mummy needs to go to the hospital every day for a few weeks, so Daddy will be taking you to preschool/school instead.”

“Grandpa is sick so we won’t see him for a while. He loves your pictures, so maybe you can draw me some to take to hospital.”

“Mummy has to stay in bed a lot and isn’t able to play, but she can still cuddle you.”

Younger children

“The doctors will take good care of me. I will have treatment soon, which I’ll tell you about when it starts.”

“Even though things might change a bit at home, you’ll still be able to go to tennis lessons while Dad is having his treatment.”

“Mum is going to be busy helping Grandma after she comes out of hospital. There are ways we can all help out, but mostly things will stay the same for you.”

Older children and teenagers

“Things will be different while Dad’s having treatment, and when I can’t drive you to soccer training, Annie will drive you instead.”

“After my operation, there are a few things I won’t be able to do for a while, like lifting things and driving. Our friends are going to help by dropping off meals.”

“If you have any questions or worries, you can come and talk to me. It’s okay if you want to talk to someone else too.”

"It is often helpful to talk to other parents who have or have had kids at a similar age to yours when diagnosed. Talking to another parent who has travelled the same road can be reassuring.” MIRA, MOTHER OF TWO CHILDREN AGED 3 AND 12

Involving others

There are several ways to ensure kids hear a consistent message from people who are involved in their lives.

Tell key adults – Share the diagnosis with other people who talk with your kids (grandparents, friends, the nanny, babysitters) and tell them what you plan to say to your children so that you all communicate the same message.

Talk to other people who have cancer – Often the best support and ideas come from people who’ve already been there. You’ll realise you’re not alone and you can ask them how they handled things.

Ask a professional – It may also be helpful to get some tips from a professional, such as an oncology nurse or social worker, psychologist or other health professionals at the hospital.

Involving the school or preschool

Many parents wonder if they should tell the school when someone in the family has been diagnosed with cancer. If things are unsettled at home, school can be a place where kids can be themselves with their friends and carry on life as normal.

When the school is aware of the situation at home, staff may be more understanding of behaviour changes and can provide support. In fact, school staff are often the first to notice shifts in a child’s behaviour that may indicate distress.

A cancer diagnosis in the family can also have an impact on academic performance, so the student may be entitled to special provisions. This can be particularly important in the final years of high school. Some states and territories have schemes to help a student enter tertiary study if they have experienced long-term educational disadvantage because of their or a family member’s cancer diagnosis.

Ways to involve the school include:

- Tell the principal, the school counsellor and your child’s teachers. This helps the school to create a positive and supportive environment for the student.

- Let relevant staff know what your child has been told about the cancer and what they understand cancer to mean, so staff can respond consistently.

- Ask the school to let you know of any changes in behaviour or academic performance. Ideally, a particular staff member, such as the class teacher, student wellbeing coordinator or year adviser, can provide a regular point of contact with the student. However, request that teachers don’t probe – some well-meaning staff members might misinterpret your child’s behaviour and unintentionally make them feel uncomfortable. For example, a teacher may ask if your child is okay when they’re happily sitting on their own.

- If you feel concerned about your child, ask the principal whether your child could see the school counsellor.

- Sometimes other children can be thoughtless in their comments. Talk to your child about how other children are reacting and encourage them to tell you if they have any concerns. You can raise these issues with teachers if needed.

- Ask a parent of one of your child’s friends to help you keep track of school notes, excursions, homework and other events. When life is disrupted at home, children may feel doubly hurt if they miss out on an event or activity at school because a note goes missing.

- Explore what special provisions might be available for exams or admission into university.

Support services for schools

You may want to let the school know about services that provide school visits and information about cancer. For primary school and preschool children, Camp Quality offers a cancer education program, featuring puppets, to help young students learn about cancer in a safe, age-appropriate way.

For older children, Canteen has a cancer awareness program called “When Cancer Comes Along”.

For more ideas about how your child’s school can help, download our book ‘Cancer in the School Community: A guide for staff members’. This book explains how school staff can provide support when a student, parent or staff member has cancer.

Key points: Talking about the diagnosis

- Discuss the diagnosis with trusted adults first if you need to.

- Ask for practical and emotional support from relatives, friends or work colleagues.

- Work out the best time to talk to your children.

- Decide who you want to be there with you.

- Tell your children what has happened.

- Explain what is going to happen next.

- Assure them they will continue to be loved and cared for.

- Approach the initial conversation as the first of many discussions.

- Let them know it’s okay to feel scared or worried, and talking can help.

- End the discussion with expressions of hope.

Talking about treatment

Cancer treatment can be challenging for the whole family, but children and young people often manage better when they know what to expect. How much detail you provide will depend on the child, your values and your cultural background; in general, kids like to know what the treatment involves, how it works, and why there are side effects. While you may not be able to say exactly what will happen, you can promise to keep your children updated.

What do children need to know?

Providing children and young people with information about the treatment, why and how it is done, and possible side effects can help them to understand what to expect in the weeks and months ahead.

Outline the treatment plan

- Let the children be your guide as to how much they already know and how much they want to know about treatment.

- Start with questions such as “Have you heard the word chemotherapy?” or “Do you know what radiation therapy is?”. Then explain the basic facts using language they can understand.

- Check if your kids want to know more, and let them know that they can ask questions throughout the treatment period if they have other queries or concerns.

- Talk to kids about how to search for accurate information online, to avoid incorrect or unhelpful information.

- Keep them up to date with how long treatment will take and the length of the hospital stay.

- Explain who will be taking care of the person with cancer and the different ways the carers will help.

Explain side effects

It’s important to prepare children for treatment side effects, such as weight changes, fatigue, nausea, scars and hair loss.

Explain that not everyone gets all side effects. People who have the same cancer and treatment will not necessarily have the same side effects. Doctors know what happens to most people having a particular treatment but can’t be exactly sure what will happen to each person – everybody is different.

Tell your children what side effects to expect, based on what the doctor has said, and how these may change how you look or feel. Say you’ll let them know if you start to experience these side effects.

Talk about ways your children can help you deal with the side effects (e.g. help shave your head or choose a wig). Such actions make your children feel like they’re being useful.

Let them know that the doctors will try to make sure treatment causes as few side effects as possible. They should know that side effects usually go away after the treatment is over – hair will grow back, scars will fade – but this often takes time.

Reassure your children that they will get used to the changes. Point out that you’re still the same person as before.

Side effects do not mean that you’re getting worse. It’s common for kids to get upset on chemotherapy session days when they see the effects of the drugs, which may include fatigue or vomiting. They may worry that the treatment is making the cancer worse or that the cancer

has progressed.

Let your children know that these treatment side effects are separate to the cancer symptoms. If there are no side effects, reassure them that this doesn’t mean the treatment is not working.

If side effects mean you can’t join in usual family activities, make sure your children understand that it doesn’t mean you’re not interested.

Explain to them how much of the side effect is considered normal. This can be especially important for older teenagers who might worry about when they should call for help.

"When my ex-wife got breast cancer, I talked to my little girl about how the treatment caused changes, like Mummy would get very tired and her hair would fall out, but we expected her to be okay.” SIMON, FATHER OF A 4-YEAR-OLD

Hospital visits

Cancer treatment can involve short but frequent visits to the hospital as an outpatient (day treatment) or a longer stint as an inpatient (staying one or more nights). A visit to hospital can seem strange and confronting for a person of any age, but especially for children. They may have to have a COVID test and wear a mask.

You may worry that your children will get anxious if they see people with cancer in hospital or having treatment. If you are a parent with cancer, however, you may also worry about your kids being separated from you.

Reassure them that hospitals are special places where people are given good care; children’s fears may be worse than the reality. Ask your kids if they want to go to the hospital or treatment centre. If they would prefer not to go, don’t insist on them visiting.

Preparing for a hospital visit

If children are keen to visit, the following tips may help prepare them.

- Before children enter the hospital room, tell them what to expect and what they may notice: the equipment; different smells and noises (e.g. buzzers, beeps); how you may look (e.g. tubes, bandages, a drip or catheter bag full of urine hanging on the side of the bed); doctors and nurses might keep coming in and out to check on the patients. You may be able to arrange with the nursing staff for children to look at pictures or see some of the equipment in an empty room before visiting you.

- If your kids are reluctant to go to the hospital, their first visit could just be to the ward lounge room. Reassure them that this is okay and that they can send a card or call, if they prefer.

- Let your kids decide how long they want to stay. Small children tend to get bored quickly and want to leave soon after arrival. They may want to help by getting you a drink or magazine from the hospital shop.

- Have a friend or relative come along. They can take the kids out of the room if they feel overwhelmed and then take them home when they’re ready to leave.

- Bring art materials, books or toys to keep them occupied. Older children may want to play cards or board games with you. Or you could simply watch TV or listen to music together.

- If you have to travel for treatment and your children are unable to visit, use video calling on a mobile phone to communicate.

- If the hospital stay will be longer, ask the kids to make the room cosy with a framed photo or artwork they’ve made.

- After the visit, talk to them about how they felt and answer any questions they may have.

- Ask the staff for support. Nursing staff and hospital social workers are sensitive to children’s needs during this difficult time and could talk to your children if necessary.

How to play in hospital

If your child is visiting you – or a sibling or friend – in hospital, explain beforehand that you may not feel well enough to play or talk much but will be happy that they care enough to visit. Some activities you could try include:

- card games

- board games

- drawing games, such as folding a sheet of paper into thirds then taking turns to draw the head, middle and legs of a character

- charades

- shared imaginary play with toys

- simple craft

- using your laptop or tablet to watch a favourite movie or program together.

Cancer and COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many changes, including increased awareness of the importance of hygiene. When cancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy) affects a parent’s or a child’s immune system, family members may become anxious about hygiene and go to extra lengths to protect their family from COVID-19 or other infections. You can reassure children and teenagers that routine hygiene practices are okay, and that you will tell them if extra measures are needed.

Creative ways to explain cancer and its treatment

Sometimes talking isn’t the best way to communicate with children and teenagers. A range of creative methods can help explain cancer treatment and explore feelings. You can adapt these suggestions for different ages and interests.

Make up stories and play games – Try explaining cancer treatment using stories they know, or by playing games. For younger children, you could play a game of popping “cancer bubbles” to make them go away. Blow some bubbles in the air and challenge your children to pop these cancer bubbles – or bad cells – by jumping, slapping, or stomping on them. You can explain to your children that the chemotherapy or radiation therapy is “popping” the cancer cells, just like they are popping the bubbles.

Visualise it – Draw a flow chart or timeline to show the different stages of the treatment plan. At different times throughout treatment, you can look at the chart together to see where you are up to and how far you have come.

Offer them a tour – Before treatment starts, give your children a tour of the treatment centre or hospital ward. Check with staff whether this can be arranged. This experience will give your children a clearer idea about what happens during treatment. They can picture where the person with cancer will be and meet the medical team. Older children are often particularly interested in how the treatment technology works. If a hospital visit is not possible, consider

organising a video tour.

Say it with music – Listening to different types of music together or getting kids to make up their own music could help with their understanding of the different treatments (e.g. using

percussion to represent destroying the cancer cells, or listening to a lullaby to represent falling asleep before having an operation).

Keep a journal – Keeping a personal journal or diary can help older primary schoolchildren and teenagers to express their feelings. Some may prefer to write a short story that is based on the cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Draw out feelings – Use art as a way to talk about cancer treatment. Ask your kids to draw what they think cancer is or how different treatments work. Their artwork can show a lot about what they understand or are feeling.

Answering key questions

Q: Is it going to hurt?

Cancer doesn’t always cause pain, and if it does, the pain can be relieved or reduced. How you answer this question will depend on the child’s age.

For younger children, you may say: “Cancer doesn’t always hurt, but if I have pain, the doctors will give me medicine to help make it go away.”

For older children and teenagers, you may say: “The cancer treatment may cause me pain. The doctors can give me medicines for pain, but I might have good days and bad. I’ll let you know if I am having a bad day.”

Q: Why do you look so sick when the doctors are meant to be making you better?

Often people who have cancer look perfectly well when diagnosed. It’s only when they have treatment and the side effects kick in that they start to look sick. This can be hard for children to understand.

“The doctors are using strong medicine to kill the cancer, but the medicine affects good cells as well as cancer cells. Some days I might feel and look sick, but this doesn’t mean the cancer is getting worse. I will start to feel better when treatment finishes.”

Q: Will your hair come back?

Hair loss can be upsetting for you and your children, so it can help if the family knows what to expect and what you might do about it.

“The doctor says I may lose my hair because of the chemotherapy. I can wear wigs, scarves or hats until it grows back.”

Q: Does radiation therapy make you radioactive?

A common fear among children is that they can become radioactive by touching you after radiation therapy. With most types of radiation therapy, this is not possible. Your doctor will tell you if you need to take any precautions.

“Radiation therapy is like an x-ray. It doesn’t hurt. It’s safe to touch me.”

Q: Why do you need to rest so much?

Children often can’t understand the exhaustion you may feel after treatment. They may resent you not doing as much with them.

“The operation/treatment I’m having has made me tired and I need to rest so my body can recover. Let’s make a plan for what we’ll do on a day I have more energy. Perhaps today we can do something quiet like watch a movie.”

Family life during treatment

If you are a parent with cancer, you may be keen to keep life as normal as possible for your kids during treatment. But this can be challenging when you are coping with treatment and recovery, because of frequent trips to the hospital, changes to your appearance or lower energy levels. You may feel guilty about not being able to do all the usual things with, and for, your kids. You may try to push yourself to keep going, but some days this may not feel possible.

There are no easy answers to this problem, but you can make the most of your good days by forgetting the housework and doing fun things with the family. On the not-so-good days, let your kids know, rather than trying to protect them from the reality of how you’re feeling.

Acknowledging disappointment

It is normal for children to think mostly of themselves and how a situation affects them. Some older children and teenagers may seem annoyed about the diagnosis and uncaring of their parent. You may find their reaction hurtful or frustrating, but it is age-appropriate. Other

teenagers may take on too much responsibility around the house, and lose touch with their friends. It’s also important for them to maintain social networks.

It can be helpful to acknowledge your child’s disappointment: “I know you’re finding it frustrating that I can’t watch you play soccer like I usually do, but I am not feeling well and I just need some quiet time right now.”

It’s also important that children and teenagers understand that how they behave won’t affect your health and recovery. Children can sometimes feel that if they are not quiet, their parent won’t get better. You may like to tell younger children: “I know you feel upset that I can’t play with you. I am sad too, but I am very tired. Let’s think about what we can do tomorrow when I feel better.”

If you are a parent caring for someone with cancer, such as your partner or your own parent, you may feel like you have little time and energy left for your children. Although asking for and accepting help can be difficult, it may relieve some pressure and allow you to spend more time together as a family.

Download our book ‘Caring for Someone with Cancer’ which discusses ways to look after yourself and how to take a break and includes a list of support services for carers. Call

13 11 20 if you would like a free copy.

Managing emotions

Everyone responds differently to the treatment phase. Anger, crying and withdrawal are some of the possible reactions. These can be protective responses that allow a child or young person time to deal with the information.

Some children may hide their feelings because they do not want to add to their parents’ stress. Even if your child’s behaviour doesn’t suggest they are struggling, let them know you appreciate how hard this situation is for them.

Children will express their emotions differently depending on their age and nature. If your kids’ reactions seem unusual or extreme, consider getting some professional support.

- There are many ways to help children to understand and manage their emotions. These include:

- Encourage, but don’t push, kids to identify and name feelings. For younger children, you may need to recognise and identify the emotion for them (e.g. “You seem like you might be angry” or “You seem really worried”).

- Reassure them that there are no right or wrong feelings. Everyone reacts in their own way.

- Let them know that anger, guilt and sadness are normal feelings. You feel them too and it is okay to talk about them.

- Remind them that they can talk to you about how they’re feeling at any time.

- Discuss ways to manage anxiety and stress.

- Make sure they have plenty of opportunities for physical activity and spending time with friends.

- Provide plenty of physical comfort, such as hugs and cuddles.

- Offer creative ways for children to express their emotions.

- Create everyday opportunities for humour and fun. Let your children know that it is alright to joke and enjoy themselves. Laughter can often relieve tension and help everyone relax.

The emotions thermometer

The physical and emotional health of a person with cancer will vary during and after treatment. It can sometimes be hard to let your family know how you’re feeling, and they might find it hard to ask.

An emotions thermometer may help. This simple tool allows you to show how you’re feeling every day. You can make one yourself and ask the kids to help, or there are many versions available online. Just search for “emotions thermometer”. Choose which feelings to include

and add a pointer that moves to the different feelings.

Put the emotions thermometer up where everyone can see it, such as on the fridge or noticeboard.

Encouraging family time

Maintaining routines and family traditions as much as possible will help children and young people feel safe and secure. Sometimes you have to strike a balance between doing regular activities and coping with the effects of the cancer.

If you need to change a regular routine during treatment, tell children what the change will be, why it’s occurring and how it will affect them. They will probably want to know who will look after them, such as who will take them to school or sport or do the cooking. Tell your children where you’ll be, such as at the hospital or resting at home.

If you or your family members can’t get them to their after-school activities, arrange for a friend or relative to help out. If that’s not possible, you may have to cut back on the activities for a while, but involve your children in the decision.

During treatment, when life may be disrupted and unsettled, try to protect the time your family has together. Here are some ideas:

- Some families may limit visitors and choose not to answer any phones at mealtimes. Others may welcome some visitors at this time.

- You may want to set some boundaries around when friends phone you, or you might ask them to send an email or keep in touch through social media platforms. There are many ways to keep family and friends updated on how you are doing. You may use a closed Facebook group, set up a chat group on a messaging app, or use Caring Bridge.

- Think of things to do together that don’t require much energy. You could read a book aloud, watch a movie, or play a board game or a video game.

- Ask a close friend or relative to coordinate all offers from friends and family to help out with household chores. To help coordinate offers of help, you may choose to use an app, such as Gather My Crew or KiteCrew.

- Plan for “cancer-free” time with the family where you don’t focus on the illness but do fun things that allow you to laugh, joke and relax.

Camp Quality Family Retreats offers holiday accommodation to families affected by cancer. This is often the first break a family has after a cancer diagnosis, and it gives them the chance to relax and reconnect.

Spending one-on-one time

When a family member is diagnosed with cancer, it can be difficult for parents to spend one-on-one time with their children. One way to focus your attention and care is to schedule a weekly 30-minute session with your child or teenager. This may help them feel important, valued and understood.

Talk with your children about the type of activities and family time that are important to them. If you have more than one child, you may need to alternate weeks for one-on-one time depending on your energy levels.

A younger child may not have developed the thinking or language skills to describe how they’re feeling, but a play session can help the child to express feelings, make sense of events, and understand the world. They may:

- act out a story with toys or puppets

- use fantasy and dress-up

- draw, paint or play games

- talk about their experience.

During a play session, comment on what they’re doing using empathy or observation, which will let them know that you are interested in what they are doing, saying and feeling. They may play on their own or invite you to play with them. Avoid asking questions or correcting your child. This time is for them to lead the way. Their play may reveal an inner world that you may never have known about from what they say.

It’s common for teenagers to prefer spending more time with friends, but they may like to visit a favourite cafe, go for a walk, watch a movie or listen to music with you.

Maintaining discipline

It can be hard enough to maintain family rules when you’re fit and healthy, let alone when you’re dealing with the emotional and physical effects of cancer treatment or caring for someone with cancer. Some parents say they feel guilty for putting the family through the stress of cancer, so they don’t want to keep pushing their children to do homework and chores.

The issue of discipline is a common concern for families dealing with cancer. Maintaining the family’s usual boundaries and discipline during this time can strengthen your children’s sense of security and their ability to cope.

Keeping up children’s chores, encouraging good study habits, calling out inappropriate behaviours, and sticking to regular bedtimes – all require continued and ongoing supervision from adults.

Some children may misbehave or push the boundaries to get the attention they feel they are missing.

Although some flexibility may be reasonable at this time, a predictable set of boundaries and expectations can help to maintain a sense of normal life and will be reassuring for children and young people. Let teenagers know that the usual rules apply for curfews, drug and alcohol use, and sex.

Encouraging children to help

When a family is dealing with a cancer diagnosis, children may need to take on extra responsibilities. If children feel they are being useful at this time, it can boost their self-esteem because it shows that you value and need them.

Young children can help with simple tasks. With older children and teenagers, it’s reasonable to want them to help more around the house, but it’s important to talk to them first.

Try to avoid overloading teenagers with household chores and try to share tasks fairly among all family members. Jobs that need to be done are not always obvious to older children, so discuss priorities and how tasks can be divided up.

When asking teenagers to help with household chores, keep in mind that it is age-appropriate for them to spend time with their friends as well. Missing the opportunity to socialise with their peers can make them feel resentful at a difficult time and affect their self-esteem. It may also cause them to be socially isolated from friendship groups.

Helping around the house

The internet is a good source of information about appropriate jobs around the house for children of all ages. Try searching for “age-appropriate chores”. Some possibilities include:

Ages 2-4

- put toys into toybox

- put books back on shelf

- put clothes into dirty washing basket

Ages 4-8

- set table

- match socks

- help make bed

- help dust

- help put away groceries

Ages 8-12

- make bed

- feed pets

- vacuum

- load and empty dishwasher

- rake leaves

Over 12

- make simple meals

- clean kitchen

- clean bathroom

- wash and hang out clothes

- wash dishes

- wash car

This can be a time to reflect on priorities and what really matters for your family. You might choose to let go of some household tasks that you previously thought were essential.

Single-parent families

In any family, a cancer diagnosis can make it challenging to meet everyone’s needs. If you are the only parent in your household, cancer may come on top of an already heavy domestic, financial and emotional load.

Your children will need to help but may end up taking on more responsibility than they are ready for. Ask your friends and extended family to support them. You can also find out what support services are available in your area by calling Cancer Council 13 11 20.

You may want to get in touch with Carers Australia Young Carers Network. This organisation runs activities and support groups for young people (aged up to 25 years) who care for a parent with a serious illness. Even young children may be considered young carers – for example, if they are helping with cooking or cleaning. Camp Quality and CanTeen can also offer support to children when a parent has cancer.

Staying in touch

If you need to travel for treatment, or if you have extended hospital stays, you may be away from your family for long periods. In some cases, both parents may need to travel to a major hospital and leave their children with family members or friends. The following tips may help you stay in touch. They might also be useful if you don’t need to leave home but want extra ways to communicate with your kids.

- Ask your kids to do drawings and take photos to send to you.

- Set a time to call home each night when you’re away, then read a favourite story together over the phone or via video calling (e.g. FaceTime, Zoom or Teams).

- Write an old-fashioned letter. Kids love finding mail addressed to them in the letterbox.

- Send an email or recorded message.

- Leave notes and surprises for kids to find, such as a note in a lunch box.

- Connect through social media.

- Use private messenger apps for one-on-one chats with teenagers.

- If they’re able to visit, children can bring cards or pictures from home, flowers picked from the garden, or a toy to “mind” you in hospital.

Key points: Talking about treatment

- Explain treatment to children as simply as possible.

- Don’t be afraid to be creative or have fun with your explanations.

- Let kids know how treatment works and how side effects may change the person with cancer.

- Encourage your kids to ask questions and express any fears or worries about the cancer treatment.

- Try to keep life at home as stable as possible and allow kids to continue their regular activities.

- Realise that children and adults alike may become intensely emotional occasionally.

- Maintain boundaries as much as possible.

- Let all children help out around the house.

- For teenagers, let them know their help is appreciated but not expected.

- Reassure your family if you expect there to be better days ahead.

- Spend time just with your family.

After treatment

For many people, the end of active treatment is a time of relief and celebration, but it can also be a time of mixed emotions. Children and teenagers may expect life to return to normal straightaway, but the person who has had treatment may be re-evaluating their priorities. Your family might need to find a “new normal”.

What do children need to know?

It may help children and young people to know that cancer can be a life-changing experience for many people. Once treatment has finished, some people want life to return to normal as soon as possible, while others feel they need to re-evaluate their life.

This process is often called finding a new normal, and it may take months or years. The person who has completed cancer treatment may:

Make changes – This period can be unsettling and lead to big life changes, such as choosing a new career, reassessing relationships, improving eating habits or starting a new exercise program.

Continue to feel the physical impact – The physical effects of cancer sometimes last long after the treatment is over. Fatigue is a problem for most people who have had cancer treatment and it can make it difficult to complete everyday activities. Many people have to cope with temporary or permanent side effects.

Worry about recurrence – One of the major fears people have is that the cancer might come back. This is an understandable concern, which can be triggered by regular check-ups and even minor aches and pains.

For more information, download our ‘Living Well After Cancer’ booklet, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for a free copy.

How children react

Like many adults, children may find it hard to understand why things simply can’t go back to the way they were before the cancer. They’ve had to deal with changes while their parent or other family member was sick, and now they probably want to get back to normal. Your kids may:

Expect the person who had cancer to bounce back – Often children don’t understand that fatigue can continue after cancer treatment is over. This can lead to disappointment and frustration.

Become clingy – Separation anxiety that started during treatment may continue well after treatment is over.

Worry the cancer will return – The cancer returning is often a big fear for children and young people, just as it is for the person who had cancer. You can reassure children that regular check-ups will help monitor for cancer.

Carry on as if the cancer never happened – Some children may move on in life as if the cancer never happened.

Family life after treatment

You may celebrate the end of cancer treatment and acknowledge that it has been a difficult period for everyone; this is particularly important for teenagers. Your children have lived with worry for months and may need your permission to relax and have fun again. Thank them for their role in keeping the family going and supporting you.

Let the family know how you’re feeling emotionally and physically so they understand if you’re not bouncing back as quickly as they expected. It may be helpful to remind your family that treatment effects are likely to last for a while after treatment finishes.

Keep using the emotions thermometer if you have found it helpful. Be open about your fears, such as if you’re feeling anxious before a check-up. This may encourage your kids to talk

about their own fears.

Do things at your own pace, and avoid any pressure to return to “normal” activities. You may want to ask yourself: Am I doing what fulfils me? Am I doing what I want to do? What is important to me?

Explain any changes to the family’s lifestyle to your children and negotiate where possible. During your recovery, you may be able to encourage your family to join you in making some healthy lifestyle changes – for example, you could do light exercise together, or make healthy changes to the kids’ diets as well as your own.

Expect good days and bad days – for both the adults and the children in the family. Focus on one day at a time.

Answering key questions

Q: Will the cancer come back?

You probably wish you could tell your children that everything will be fine now, but the uncertainty of cancer often lasts long after treatment is over. Along with giving your children a hopeful message, this may be a chance to listen to their concerns about “What if?”. Allowing children to talk about their fears and concerns is important in helping them cope.

“The treatment is over and we all hope that will be the end of it. We hope that the cancer won’t come back, but the doctors will keep a careful eye on the cancer with check-ups every now and then. If the cancer does come back, I will have some more treatment, which we hope would make it go away again. We’ll let you know if that happens.”

Q: Why are you still tired?

Cancer survivors often feel tired for many months after treatment. This can be hard for kids who want their energetic parent, grandparent or friend back.

“I’m feeling a lot better, but the doctor said it might take many months, even a year, to get all my energy back.”

“The treatment was worth it because now I’m better and the cancer has gone away, but it took a lot out of me and now my body needs time to recover. This is normal for people in my situation.”

Q: Can’t we get back to normal now?

You may need to take some time to process the ways that cancer has affected you, but this will probably be difficult for children, particularly younger ones, to understand.

It may be helpful to explain that not everything will be the same as it was before, but that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. The new normal could actually offer some benefits. Many people who’ve had cancer can see positive outcomes from the experience, and it may help to

highlight these to the kids.

“Day-to-day life will start to get more like normal as I feel better, but there may be some changes to the way we do things, like … [the way we eat/how much I go to work/how much time we spend together as a family]. Maybe we can also find some new hobbies to do together.”

“We’ve all been through a lot and I know it’s been hard for you too. Things might not get back to exactly how they were before I got sick, but together we can find a new way that works for all of us.”

Key points: After treatment

- People who have had treatment for cancer often have mixed emotions.

- It may be difficult to settle back into how life was before the cancer diagnosis.

- Kids and young people might continue to have their own fears and worries about the cancer.

- Children may find it hard to understand why life can’t go back to normal. It could help to explain that the family will have to find a new normal.

- Give your children permission to have fun and to re-establish their own new normal along

with you. - It’s important to keep communicating and sharing your feelings with each other.

Living with advanced cancer

This section is a starting point for talking to your children if someone they love has cancer that has come back or spread. The issues are complex, emotional and personal, so you may find reading this information difficult. If you want more information or support, talk to hospital staff or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

What do children need to know?

For some people, the cancer may be advanced when they are first diagnosed. For others, the cancer may spread or come back (recur), even after the initial treatment seemed to be effective.

Living longer with advanced cancer

More and more people with advanced disease are surviving for longer periods of time. Treatment can often keep the cancer under control and maintain quality of life for many months, and sometimes for many years. When this happens, the cancer may be considered a chronic (long-term) illness.

If the cancer has advanced, it is important to keep talking with your children. Just as with the initial diagnosis, children may sense that something is happening, and not telling them can add to their anxiety and distress.

Children may have similar feelings to adults after hearing the cancer has advanced. These include shock, denial, fear, sadness, anger, guilt or loneliness.

Uncertainty about what the future holds will be a challenge for both you and your children. You may be able to reassure children that, although the cancer cannot be cured, there are treatments that can help you feel better and you may be able to stay well for a long time.

Remember that the concept of time can be different for younger children. While several years might seem to be a short time to you, it can seem like a long time for children.

Offering realistic hope

A diagnosis of advanced cancer does not mean giving up hope. Some people with advanced cancer can continue to enjoy many aspects of life, including spending time with their children and other people who are important to them.