Cancer and its treatment may affect a person’s ability to conceive a child or maintain a pregnancy (fertility). The information on these pages helps you understand how cancer treatment can affect fertility.

Whether or not you want to become a parent or add to your family, you may be wondering how cancer will affect your fertility. We hope this information will help you understand how you may be able to try to keep (preserve) your fertility before and during cancer treatment, and your options after cancer treatment. We cannot give advice about the best ways to preserve fertility. You need to discuss this with your doctors.

When talking about the body, we use the terms “female” and “male”. Some people may identify with a different sex or gender.

What are reproduction and fertility?

Reproduction is the way we produce babies. Knowing how your body works may help you understand how fertility problems happen.

How reproduction works

The female and male reproductive systems work together to make a baby. The process involves combining an egg (ovum) from a female and a sperm from a male. This is called fertilisation.

Role of hormones – These substances are produced naturally in the body. Hormones control many body functions, including how you grow, develop and reproduce. The pituitary gland in the brain releases hormones that tell the ovary and adrenal gland to make sex hormones.

Oestrogen and progesterone, often called female sex hormones, are produced in the ovaries. These hormones control the growth and release of eggs, and the timing of periods (menstruation).

Androgens are often called male sex hormones. The major androgen is testosterone, which is produced mainly in the testicles, but also in the male and female adrenal glands and the ovary. Most people produce some testosterone, although generally men make more. It helps the body make sperm.

Ovulation – Each month, from puberty (sexual maturation) to menopause (when periods stop), one of the ovaries releases an egg. This is called ovulation.

Pregnancy – The egg travels from the ovary into the fallopian tube. Here it can be fertilised by a sperm. Once the egg is fertilised, it implants itself into the lining of the uterus and grows into a baby. After the egg is fertilised by the sperm, it’s called an embryo.

Menopause – As females get older, hormone levels fall to a level where the ovaries stop releasing eggs and periods stop. This is known as menopause. This is the natural end of the female reproductive years and it usually happens between the ages of 45 and 55.

Factors that affect fertility

Some of the common factors that affect fertility include:

- age – fertility starts to naturally decrease with age

- weight – being very underweight or overweight

- smoking – both active and second-hand smoking can harm reproductive health

- alcohol – drinking too much alcohol may make it harder to conceive

- other health concerns – endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic disease, certain hormonal conditions or cancer.

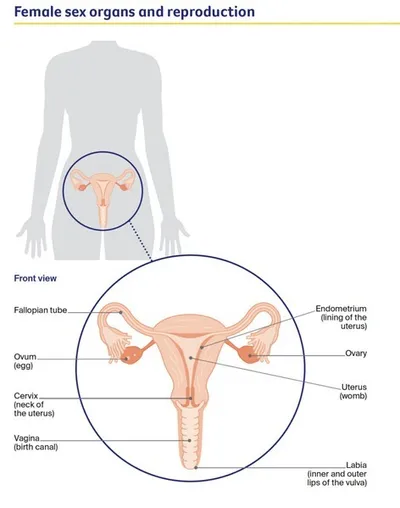

Female sex organs and reproduction

ovaries

- two small, walnut-shaped organs in the lower part of the abdomen

- contain follicles that hold immature eggs (ova), which eventually become mature eggs

- make hormones including oestrogen and progesterone fallopian tubes

fallopian tubes

- two long, thin tubes that extend from the uterus and open near the ovaries

- carry sperm to the eggs, and eggs from the ovaries to the uterus

uterus (womb)

- a hollow muscular organ where a fertilised egg (ovum) is nourished to develop into a baby

- the inner lining of the uterus is known as the endometrium; each month if an egg is not fertilised, some of the lining is shed and flows out of the body (menstruation or monthly period)

- joined to the vagina by the cervix

cervix (neck of the uterus)

- the lower, cylinder-shaped entrance to the uterus

- produces moisture to lubricate the vagina

- holds a developing baby in the uterus during pregnancy and widens during childbirth vagina (birth canal)

Vagina (birth canal)

- a muscular sheath or canal that extends from the opening of the uterus (the cervix) to the vulva

- the passageway through which menstrual blood flows out of the body, penetrative sex (such as intercourse) occurs and a baby is born

vulva

- the external sex organs; includes the labia

Male sex organs and reproduction

testicles (testes)

- two small, egg-shaped glands

- make and store sperm

- also make the hormone testosterone, which is responsible for the development of male characteristics, sexual drive (libido) and the ability to have an erection

scrotum

- the loose pouch of skin at the base of the penis that holds the testicles

epididymis

- a tightly coiled tube attached to the outer surface of each testicle

- sperm travel from the testicles through the epididymis to the spermatic cord

spermatic cord and vas deferens

- tube running from each testicle to the penis

- contains blood vessels, nerves and lymph vessels

- carries sperm towards the penis

seminal vesicles

- a pair of glands that lie close to the prostate

- produce fluids that make up part of semen

prostate

- a small gland about the size of a walnut

- produces fluids that form part of semen

- located near the nerves, blood vessels and muscles that control bladder function and erections

penis

- the main external sex organ

- urine and semen pass out of the body through the penis

- semen is made up of sperm and other fluids, and is ejaculated from the penis

Transgender, non-binary or intersex?

This information has been developed based on evidence in people born female or male.

If you are non-binary or a trans person or person with an intersex variation, this information may still be relevant to you if you have ovaries, a cervix and a uterus, or testicles and a penis. For information specific to you, talk to your doctor.

Call Cancer Council on 13 11 20 to ask for information about the specific cancer needs of LGBTQI+ people.

Fertility after a cancer diagnosis

Answers to some common questions about fertility, following a cancer diagnosis, are below.

What is infertility?

Infertility is defined as difficulty getting pregnant (conceiving). This may result from female or male factors, or a combination of both, or the reasons may be unknown. For females under 35, the term usually refers to trying unsuccessfully to conceive for 12 months; if a female is 35 or over, the term is used after 6 months of trying.

Could cancer affect my fertility?

Cancer and its treatment may affect your fertility. This will depend on the type of cancer and treatment you have.

Fertility problems after treatment may be temporary – lasting months to years – or permanent.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can damage reproductive organs involved in creating or carrying an unborn baby, such as the ovaries, uterus or testicles. Sometimes these organs are damaged or removed during surgery, which can harm or destroy eggs or sperm.

How does age affect fertility after a cancer diagnosis?

Age is one of the most important factors in how cancer treatment affects fertility.

Female age and fertility – Females are born with all the eggs they will have in their lifetime. From the age of 30, fertility starts to decline and speeds up after 35. It then becomes harder to conceive and the risk of chromosomal conditions (e.g. Down syndrome) in the eggs increases. From your early 40s, although you may still have regular periods, it is difficult to conceive a child because of poor egg quality. After menopause, it is no longer possible to conceive a child naturally.

How cancer treatments affect fertility will vary with age. Before and after puberty, the effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy on fertility can vary, depending on the drugs used or the dose.

Before puberty, high doses of drugs or radiation may sometimes cause enough damage to the ovaries that both the start of puberty and future fertility are affected. After puberty, treatment to the ovaries can cause periods to stop permanently. Even if periods return after treatment, some women may experience premature or early menopause.

Male age and fertility – The quality and quantity of sperm decreases with age. This means it may take longer for an older man’s female partner to get pregnant. Before and after puberty, chemotherapy and radiation therapy may affect sperm production and may cause infertility. The impact of radiation will depend on the dose and what organs are affected by the radiation.

What is fertility preservation?

This describes the procedures that can help preserve your fertility, for example, freezing eggs, embryos or sperm, or using injections. If a cancer treatment may affect your fertility, fertility preservation procedures are usually done before treatment begins. Your fertility may be also be protected during treatment, for example ovarian shielding or transposition.

Should I have a child after I have cancer?

This is a very personal decision. Having cancer may change the way you feel about having a child. If you have a partner, discuss your family plans together. Worrying about cancer coming back may make it hard for you to make plans, including having a child. Fertility clinics often have counsellors who can talk through your situation.

When can I try to get pregnant after treatment?

This depends on many factors, including the type of cancer and type of treatment you’ve had. Some cancer specialists advise waiting between 6 months and 2 years after treatment ends. This may be to allow your sperm or eggs to recover, and to ensure you remain in good health during this time. It’s best to discuss the timing and what contraception to use with your doctor.

If you have a hormone-sensitive cancer and are taking antioestrogen drugs, you will need to wait for 9 months after you finish taking these drugs and before getting pregnant. Discuss the risks of anti-oestrogen drugs harming an unborn baby with your cancer or fertility specialist.

Will getting pregnant cause the cancer to come back?

Research shows that for most types of cancers, pregnancy does not increase the chances of cancer coming back (recurring). Research is continuing, so it’s best to discuss this issue with your specialist.

Studies to date suggest that survival rates for people who have children after cancer treatment are no different from people who don’t have children after treatment.

Can cancer be passed on to my children?

Studies show that if one or both parents have a history of cancer, their child has the same risk of getting cancer as anyone else. Up to 10% of some cancers are caused by an inherited gene from either of the parents. This is known as familial cancer. The gene increases the risk of cancer, but not all children will inherit the gene. Even if they do, it does not mean they will develop cancer.

If your diagnosis is linked to a faulty gene, you may consider having preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) as part of IVF. This involves testing embryos for genetic conditions. Only unaffected embryos are selected and implanted into the uterus. This reduces the chance of the faulty gene being passed on to the child. Discuss PGT testing and the cost with your fertility specialist.

If you are concerned about your family history of cancer, ask for a referral to family cancer centre or genetic counselling service for advice. For a list of clinics, visit the Cancer Council Australia website.

What if I'm already pregnant?

Being diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy is uncommon – it is estimated that one in every 1000 pregnant females are diagnosed with cancer. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information about pregnancy and cancer.

Treatment during pregnancy – This may be possible, but you need to discuss the potential risks and benefits to you and the baby with your oncologist before treatment begins. In some cases, treatment can be delayed until after the baby’s birth. For some cancers, chemotherapy may be safely used after the first trimester (12 weeks), usually with a break of a few weeks before the birth.

Termination – Some people diagnosed with cancer in the early weeks of pregnancy decide to terminate the pregnancy so they can start treatment immediately.

Change in birth plan – If you are diagnosed later in the pregnancy, you may be able to have the baby before the due date.

Breastfeeding – You will be advised not to breastfeed while having chemotherapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy as drugs can be passed to the baby through the breastmilk. If you are having radiation therapy, talk with your doctor about whether it is safe to continue breastfeeding during treatment.

Will my doctor talk to me about fertility?

Fertility is an important part of health for everyone. But your doctor may not discuss whether you want children in the future if they make assumptions based on your age, sexual orientation, gender and sex characteristics or focus on starting treatment immediately. If fertility matters to you, let your health professional know.

Ask your oncologist about the chances of your treatment causing fertility problems and what you can do now if you want to have a child later (e.g. freezing eggs, or ovarian, sperm or testicular tissue). Your doctor may be able to plan treatment in ways that protect or limit damage to reproductive organs to reduce the chances of infertility after treatment. Ask to be referred to a fertility clinic or oncofertility specialist.

Tell the fertility clinic or oncofertility specialist that you are having treatment for cancer so that they can arrange an appointment for you as soon as possible. Your cancer care team may also be able to help you get an appointment quickly. The fertility clinic can give you information about:

- how your age and cancer treatment might affect fertility

- the options available to you

- how likely it is that each option will lead to pregnancy

- the costs of the different options, including long-term storage fees for eggs, sperm or embryos

- using donor eggs or sperm in the future and your legal rights and those of the child and donor.

If you have a partner, try to attend appointments together and include them in the decision-making process. You may also wish to bring a family member or friend for support.

Who else can I talk to?

There are several people who can help with fertility concerns.

Health professionals you may see

cancer specialist – might be a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, gynaecological oncologist, surgeon, haematologist or cancer care coordinator

fertility specialist – diagnoses, treats and manages infertility and reproductive hormonal disorders; may be an obstetrician, reproductive endocrinologist or urologist

oncofertility specialist – specialises in fertility care of adults or children with cancer

paediatric gynaecologist, endocrinologist, surgeon – may specialise in fertility care of children with cancer

fertility counsellor – provides support and advice for people with fertility concerns

genetic counsellor – provides advice for people with a strong family history of cancer or a genetic condition linked to cancer

gynaecological oncologist – diagnoses and treats cancers of the female reproductive system, e.g. ovarian, cervical

urologist/andrologist – diagnoses and treats diseases of the urinary system and the male reproductive system

Making decisions

It’s best to talk about ways to preserve or protect your fertility before cancer treatment begins.

Get expert advice – Most people find it helpful to talk to a fertility specialist about their fertility options. Ask your cancer specialist whether you should see a fertility specialist or oncofertility specialist. You can also get a referral from your general practitioner (GP). As well as explaining your fertility options, these specialists can help with contraception and hormone management to prevent ovulation during cancer treatment. It’s best to see a fertility specialist as soon as possible after diagnosis to prevent any delays to treatment

Ask questions – It’s important that you feel comfortable enough to ask about the possible impact of different cancer treatments on your fertility, the possible risks of having treatment to preserve your fertility and the risk of delaying treatment to have fertility treatment. You may find it helpful to plan some questions in advance and to take notes during the discussion.

It’s your decision – After a cancer diagnosis, you may feel too overwhelmed by decisions about treatment to think about fertility. Or you may be asked to make fertility decisions before you’ve given much thought to whether you want to have a child in the future. Even if you think, “But I don’t want kids anyway” or “My family is complete”, you may be encouraged to consider as many fertility options as possible to keep your choices open for the future. These decisions are personal, and you need to feel comfortable with your choices.

What to consider when making decisions

After a cancer diagnosis, you may need to make decisions about your fertility. These decisions can be difficult, particularly if you have several options to consider and you feel that everything is happening too fast

Learn more about the options – Generally, people make decisions they are comfortable with – and have fewer regrets later – if they gather information and think about the possible outcomes. Ask your health professionals to explain each fertility option, including risks, benefits, side effects, costs and success rates.

Expect to experience doubts – It’s common to feel unsure when making tough decisions. Keeping a journal or blog about your experience may help you come to a decision and reflect on your feelings.

Talk it over – Discuss the options with people close to you (such as your partner, a friend or family member) or with a fertility counsellor or psychologist. Research shows that couples who make fertility decisions together are happier with the outcome, whatever it is.

Use a decision aid – A decision aid outlines the available options and helps you focus on what matters most to you. They are available online or in booklets. Breast Cancer Network Australia has developed a resource called Fertility-related choices to help younger women with breast cancer make fertility-related decisions.

The main costs of fertility treatment

Fertility preservation can be expensive, and this may influence your decision-making. The cost of specialists and private clinics vary across Australia. You may also be able to have treatment at a fertility unit in a public hospital or a clinic that provides discounted fertility treatment for cancer patients. Ask your fertility clinic about costs.

Depending on the treatment you have, costs may include:

- fertility specialist consultations – ask if they offer a discount for people diagnosed with cancer

- medicines and blood tests

- fees for procedures (e.g. the different steps in the IVF cycle for egg or sperm collection, preimplanation genetic testing and implantation of embryos after treatment)

- day surgery, operating theatre and anaesthetist fees

- egg, sperm and embryo storage (cryopreservation) – ask your clinic about up-front payments, instalment payments and ongoing fees.

How much you have to pay will depend on whether you are a public or private patient. If you are a private patient, there may be Medicare rebates for some of these costs. Ask your fertility specialist for a written estimate of their fees and any Medicare rebates. Ask your private health fund (if you belong to one) what costs they will cover and what you’ll have to pay – some funds only pay benefits for services at certain hospitals.

Medicare will cover the cost to see a specialist only if you have a referral. The referral should list both you and your partner so you can claim the maximum benefit.

Treatment side effects and fertility

This section provides an overview of how cancer treatments may affect fertility. The most common treatments for cancer are chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery and hormone therapy. Other treatments include immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Learning that cancer treatment may affect your fertility can be distressing. If you need support at this time, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Avoiding pregnancy during treatment

Some cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy or targeted therapy, can harm an unborn baby or cause birth defects.

During treatment – Even if your periods stop during cancer treatment, you might still be fertile. You will need to use some form of contraception to avoid pregnancy while having treatment.

After treatment – Your treatment team and fertility specialists may also advise you to wait between 6 months and 2 years before starting fertility treatment or trying to conceive naturally. How long you have to wait will depend on the type of cancer treatment you’ve had.

Using contraception – Your team may also advise you to use barrier contraception (such as a condom, female condom, dental dam or diaphragm), “the pill” or hormone implants, or non-hormone-based contraception (IUD) for a short time after each treatment, even if there is no risk of pregnancy.

Barrier contraception will also protect your partner from any chemotherapy drugs that may be present in your body fluids.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. These drugs travel throughout the body and are designed to affect fast-growing cells such as cancer cells. This means chemotherapy can also damage other cells that grow quickly, including those in the ovaries and testicles. The risk of infertility depends on the type of drugs used, the dose and your age.

Effect on ovaries – Some chemotherapy drugs can stop the ovaries from working properly and releasing eggs (ovulation). If chemotherapy destroys or damages eggs, your body won’t be able to replace them.

Chemotherapy drugs can cause your periods to become irregular or even stop for a while. Depending on your age, number of eggs and the amount of chemotherapy you’ve had, your periods may return within a year of finishing treatment. If your periods do not return, the ovaries may have stopped working permanently, causing premature or early menopause.

Effect on testicles – The effects of chemotherapy on the sperm you make may be temporary or permanent. Chemotherapy can cause permanent infertility if the cells in the testicles are too damaged to produce healthy, mature sperm again.

Effect on your heart and lungs – Some chemotherapy drugs can affect your heart and lungs. If this causes long-term damage, it may make a future pregnancy and delivery more difficult. Your specialist will talk to you about what precautions to take during pregnancy.

If you have both chemotherapy and radiation therapy (chemoradiation) to treat cancer, the risk of permanent infertility is higher.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. It can be delivered from outside the body (external beam radiation therapy) or inside the body (usually brachytherapy).

The risk of infertility will vary depending on the area treated, the dose of radiation and the number of treatments.

Radiation therapy to the pelvic area or any of the reproductive organs commonly causes permanent infertility. It may be used for cancer of the bladder, bowel, cervix, ovary, prostate, rectum, anus, uterus, vagina or vulva. Your treatment team may try to preserve your fertility by shielding or protecting your organs during radiation treatment, but sometimes this is not possible.

Radiation therapy to the ovaries – This can stop the ovaries producing hormones, and cause permanent menopause. If you need radiation therapy near the ovaries, one or both may be surgically moved higher in the abdomen and out of the field of radiation. This is called ovarian transposition (oophoropexy).

Radiation therapy to the cervix or uterus – This can stop the ovaries producing hormones, and cause permanent menopause. Radiation therapy can also permanently damage the uterus, which means you cannot carry a baby.

Radiation therapy to the testicles – This can lower the number of sperm and affect the sperm’s ability to work normally.

Radiation therapy to the prostate – This may cause erectile dysfunction, which means not being able to get and keep an erection firm enough for penetrative sex.

Radiation therapy to the brain – This may damage the pituitary gland, which releases hormones that control reproduction. It tells the ovaries to release an egg each month and the testicles to make sperm.

Radiation therapy to the whole body – This is known as total body irradiation (TBI), and may be given before a stem or bone marrow cell transplant to treat blood cancers. Complications such as miscarriage, premature birth and low birth weight are more common with TBI.

If you have both chemotherapy and radiation therapy (chemoradiation) to treat cancer, the risk of permanent infertility is higher.

Surgery

Surgery that removes part or all of the reproductive organs to treat cancer can cause infertility.

Removal of one or both ovaries (oophorectomy) – If one ovary is removed, the other ovary should continue to release eggs and produce hormones. You will still have periods and, if you still have a uterus, you may be able to become pregnant. If both ovaries are removed (bilateral oophorectomy) to treat ovarian cancer, you will experience immediate and permanent menopause. You will no longer have periods or be able to become pregnant naturally.

Removal of the uterus and cervix (hysterectomy) – This type of surgery may be used to treat cancer of the cervix, ovary, uterus, and sometimes, cancer of the vagina. After a hysterectomy, there is nowhere for a baby to develop and your periods will stop. Sometimes the ovaries will also be removed. If your ovaries are left in place and continue to work, you may be able to fertilise your eggs through IVF and use a surrogate to carry the pregnancy.

Removal of the testicles (orchidectomy) – Treatment for testicular cancer usually involves removing one testicle. If you have had one testicle removed, you can go on to have children naturally. However, men with testicular cancer have lower fertility rates than the general population. The urologist may advise you to store sperm at a sperm banking facility before the surgery, just in case you have fertility problems in the future.

In some rare cases, both testicles are removed (bilateral orchidectomy). This causes permanent infertility because you will no longer produce sperm. You will still be able to get an erection.

Removal of the prostate (prostatectomy) – Treatment for prostate cancer usually involves removing the prostate and seminal vesicles, and sealing the tubes from the testicles (vas deferens). This causes permanent infertility because you will not be able to ejaculate semen during orgasm. This is known as a dry orgasm. In some cases, semen may go back towards the bladder instead of forward into the penis (retrograde ejaculation.

Removal of the penis (penectomy) – Part or all of the penis may be removed to treat cancer of the penis. The part of the penis that remains may still get erect with arousal and may be long enough for penetration. It is sometimes possible to have a penis reconstructed after surgery, but this is still considered experimental and would require another major operation.

Removal of the bladder, prostate or one or both testicles – This may damage the nerves used for getting and keeping an erection (called erectile dysfunction or impotence). Erectile dysfunction may last for a short time or be permanent. It may be possible for the surgeon to use a nerve-sparing surgical technique to protect the nerves that control erections. This works best for younger men who had strong erections before the surgery. However, problems with erections are common even with nerve-sparing surgery.

Hormone therapy

Hormones that are naturally produced in the body can cause some cancers to grow. The aim of hormone therapy (also called endocrine therapy or androgen deprivation therapy, ADT) is to slow down the growth of these cancers by lowering the amount of hormones the tumour cells are exposed to.

Hormone therapy for breast cancer – If a cancer is growing in response to the hormones oestrogen or progesterone, the cancer cells will have hormone receptors. These are proteins found on the surface of the cancer cell. There are two main types of hormone receptors: oestrogen receptors and progesterone receptors. Cancer cells with hormone receptors on them are said to be hormone receptor positive or hormone-sensitive cancers. They are likely to respond to hormone therapy.

Anti-oestrogen drugs (such as tamoxifen) are used to reduce the risk of oestrogen-sensitive breast cancers coming back after treatment. Many anti-oestrogen drugs are taken for 5–10 years. Pregnancy should be avoided while taking the drugs and for 9 months afterwards, as there is a risk the drugs could harm an unborn child. These drugs can cause menopause symptoms, although they don’t bring on menopause. Anti-oestrogen drugs do not damage the ovaries or eggs. Males with breast cancer who are taking the drug tamoxifen may experience increased sperm production.

Although hormone treatments for breast cancer are used for many years, ask your doctor if it is possible to take a break from the drugs to try for a baby.

Hormone therapy for cancer of the uterus – Some cancers of the uterus grow in response to oestrogen. Hormone therapy may be given if the cancer has spread or if the cancer has come back, particularly if it is a low-grade cancer.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer – The hormone testosterone helps prostate cancer to grow. Hormone therapy may reduce how much testosterone your body makes and help slow the growth of the cancer or even shrink the cancer, but it may also cause infertility.

Other treatments

Stem cell transplant – For a small number of people with blood cancers, high-dose chemotherapy and, sometimes, a type of radiation therapy known as total body irradiation are given before a stem cell transplant to kill the cancer cells in the body. The risk of permanent infertility after high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy is high.

Immunotherapy and targeted therapy – The effects of these newer drug therapies on fertility and pregnancy are unknown, but are likely to vary depending on the drug you take. Talk to your cancer or fertility specialist about how these treatments may affect your fertility.

Managing fertility and treatment

Talk to your doctor –If you think you may want to have children in the future or if you’re not sure, discuss ways to preserve or protect your fertility with a fertility specialist before starting treatment.

Talk to your partner – Share your feelings about any fertility concerns with your partner, who may also be worried or grieving.

Use contraception – Ask your doctor what precautions to use during treatment. You may need to use barrier contraception, such as condoms or female condoms, to reduce any potential risk of the treatments harming a developing baby or being toxic to your partner.

Avoid pregnancy – Tell your cancer specialist immediately if you or your partner becomes pregnant during treatment.

Check fertility status – Consider having tests to check if your fertility has been affected.

Specific challenges after treatment

If you still have your reproductive organs, you may be able to conceive without medical assistance after cancer treatment. However, many people experience one of the following physical issues.

Acute ovarian failure

While you’re having chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and for some time afterwards, the ovaries often stop producing hormones because of the damage caused by the treatment. This is known as acute ovarian failure. You will have occasional or no periods, and symptoms similar to menopause, before regular periods return. If ovarian failure continues for several years, it is less likely that your ovaries will work normally again.

Premature menopause

Menopause is the end of menstruation (having periods). It usually happens between the ages of 45 and 55. Menopause before the age of 40 is known as premature menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), and before the age of 45 it is called early menopause.

Premature menopause could occur immediately or many years after treatment depending on your age, type of treatment and the dose of any drugs you received. If the ovaries are surgically removed or too many eggs are damaged during treatment, menopause is permanent.

While premature menopause means you won’t ovulate, it may be possible to carry a baby if you have a uterus and have not had radiation therapy and use stored eggs or donor eggs. After spontaneous POI there is a small chance (5–10%) of becoming pregnant naturally because a remaining egg may mature and be fertilised by a sperm. The likelihood of getting pregnant after POI caused by cancer treatment is not known.

Your feelings about early menopause – How menopause affects you can vary. For some, going through menopause earlier than expected may be upsetting. It may make you feel older than your age and affect your sense of identity.

For others, not having to worry about regular periods is a positive.

It may take time to adjust to the changes you’re experiencing. Talk about how you’re feeling with a family member, friend or counsellor or sexual therapist. Some studies show that mindfulness exercises can also help.

Menopause symptoms – Most menopause symptoms are related to a drop in your body’s oestrogen levels and might be more severe when menopause starts suddenly. Common symptoms may include a dry vagina, hot flushes and night sweats, aching joints, changes in mood and difficulty sleeping.

Menopause hormone therapy (MHT) – previously known as hormone replacement therapy or HRT – may help treat menopause symptoms. MHT replaces the hormones that the ovaries stop making, and can be taken as tablets, creams or skin patches. Taking MHT may increase the risk of some diseases. If you were diagnosed with hormone-sensitive cancers such as breast cancer, you are advised not to take MHT, but there are other non-hormonal drugs available that can help.

Vaginal moisturisers and lubricants can help with vaginal discomfort and dryness. They are available over the counter from a pharmacy. For more information, talk to your doctor or ask for a referral to a specialist menopause clinic.

Retrograde ejaculation

If treatment causes retrograde ejaculation, you may be given medicine to help the semen move out of the penis as normal. This may make it possible for you to conceive naturally. Your fertility specialist can also collect some ejaculated sperm from the urine, which can be used to fertilise eggs during IVF.

Erection problems

Sometimes surgery damages the nerves that help control erections and causes erectile dysfunction. This is often a temporary problem. The ability to have erections firm enough for penetration can continue to improve for up to 3 years after treatment has finished. Some people may not get strong erections again. There are several medical options you can try. These include prescription medicine and erectile aids, which may make it possible for you to conceive naturally.

Sometimes, erection problems can be permanent. If you are not able to have penetrative sex, you may be able to have testicular sperm extraction to help you conceive.

Female options before cancer treatment

This section has information about ways you can preserve your fertility before starting cancer treatment. It’s ideal to discuss the options with your cancer or fertility specialist or oncofertility specialist at this time. Keep in mind that these methods don’t work all of the time.

If you didn’t have an opportunity to discuss your options before starting cancer treatment, you can still consider your fertility later, but there may not be as many options available.

Learn more about the options below.

Wait and see

What this is

- when no method is used to try and preserve fertility

When this is used

- when you don’t have time to consider fertility preservation

- when you choose to start cancer treatment immediately

How this works

- requires no action

What to consider

- more likely to lead to premature ovarian insufficiency

Pregnancy rate

- depends on age and cancer treatment

Freezing eggs or embryos (cryopreservation)

What this is

- the process of collecting, developing and freezing eggs or embryos as part of an in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycle

When this is used

- when you want to store eggs or embryos for use in the future – they can be stored for many years

- when you are ready to have a child, the frozen egg will be fertilised using IVF or the embryo will be implanted in your uterus

How this works

- egg and embryo freezing is part of IVF – the most common and successful assisted reproductive technology for preserving female fertility

- one cycle of IVF can take 2–3 weeks

- egg collection is done in an operating theatre as a day procedure

What to consider

- need time to have IVF before cancer treatment – your cancer specialists will advise how quickly treatment should begin

- ask the fertility clinic about the cost of storing eggs and embryos

- need sperm from a partner or donor sperm to create an embryo

- to use a frozen embryo, you will need consent from the sperm donor

- talk with your fertility specialist about whether to freeze eggs, embryos or a mix of both

- legal limits on how long eggs and embryos can be stored are different in each state and territory; ask the fertility clinic for details

Pregnancy rate

- freezing eggs works nearly as well as freezing embryos

- for every 10 eggs frozen, you can expect to get 1–4 embryos

- depending on age, the success rate of the fertility clinic and the stage at which the embryos are stored at, there may be a 25–40% chance per cycle of a frozen embryo developing into a pregnancy

Freezing ovarian tissue (cryopreservation)

What this is

- the process of removing, slicing, freezing and storing tiny pieces of tissue from an ovary so it can be used later

When this is used

- if treatment needs to start immediately

- if taking hormones to encourage egg production is unsafe

- if there is a high risk of infertility

- if the person hasn’t gone through puberty

- can be used in addition to egg freezing

How this works

- tissue is removed from your ovaries during keyhole surgery (laparoscopy); if you have abdominal surgery as part of cancer treatment, tissue can be removed at this time

- tissue is frozen until it is needed

- when needed, the tissue is thawed and put back (grafted) into the ovary

- tissue may produce hormones and eggs may develop

What to consider

- risk that storing tissue before treatment begins means it will contain cancer cells, and you may not want to put this tissue back into your body; risk is higher for people with leukaemia

- legal limits on how long ovarian tissue can be stored are different in each state and territory

- ask your fertility clinic how much you will have to pay for storage

Pregnancy rate

- there have been a small number of births worldwide from ovarian tissue removed after puberty, and several births from ovarian tissue removed before puberty

- about a third of people who have tried to use ovarian tissue to become pregnant have been successful

Ovarian transposition (oophoropexy)

What this is

- surgery that moves one or both ovaries to prevent damage to the ovaries during radiation therapy

When this is used

- when one or both ovaries are in the path of radiation therapy

- limits how much radiation the ovaries receive

How this works

- one or both ovaries are moved away from the field of radiation and stitched in place

- put back in place after radiation therapy ends

What to consider

- procedure may cut off blood supply, causing damage to the ovaries

Pregnancy rate

- depends on your age, the amount of radiation that reaches the ovaries and if you start menstruating again

Fertility-sparing surgery (e.g. trachelectomy, unilateral-salpingo oophorectomy)

What this is

- trachelectomy removes part or all of the cervix and keeps the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries in place

- unilateral-salpingo oophorectomy removes only 1 ovary

When this is used

- trachelectomy is for small tumours found only in the cervix

- unilateral-salpingo oophorectomy is for early-stage cancer found only in 1 ovary

How this works

- the uterus is stitched tight with a small opening to allow blood to pass out during a period and for sperm to enter

What to consider

- risk of miscarriage and premature birth; may have a stitch placed in what remains of the cervix to reduce the risk

Pregnancy rate

- number of births increasing

GnRH analogue treatment (ovarian suppression)

What this is

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue is a long-acting hormone that stops the ovaries making oestrogen for a short time

- may protect eggs from being damaged

When this is used

- at least 1 week before chemotherapy starts, continuing until chemotherapy finishes

How this works

- hormone injections given 7–10 days before chemotherapy starts or during the first week of treatment, then every month or every 3 months during chemotherapy

What to consider

- backup to other fertility preservation options

- can affect bone density if used for more than 6 months

Pregnancy rate

- studies show that treatment is suitable for young women with breast cancer but there is no evidence for other types of cancer

How in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) works*

- Ovarian stimulation – Hormone injections daily for 10–14 days help stimulate your body to produce more eggs.

- Egg collection – Mature egg/s are collected from the follicle using a needle guided by ultrasound.

- Egg and sperm combined – The eggs are combined with sperm from a partner or donor, or frozen (cryopreservation) for later use.

- Embryo freezing – Fertilised eggs may divide and form embryos. Embryos can also be frozen (cryopreservation) for later use. One full cycle of IVF takes about 2–3 weeks.

- Embryo transfer – A syringe and tube is used to implant embryos into your body (or a surrogate). This will usually happen after cancer treatment.

Female options after cancer treatment

Fertility options after cancer treatment may be limited. Your ability to become pregnant depends on the effects of cancer treatment on fertility, your age and whether you have been affected by premature ovarian insufficiency or early menopause. Options to consider include:

- conceiving naturally

- using eggs or embryos you harvested and stored before treatment, implanted into either your body or a surrogate

- freezing eggs or embryos after treatment ends for later use (if your ovaries are still working)

- using donor eggs or embryos.

Checking fertility after treatment

Before trying to conceive, you may want to do some tests to see how your fertility has been affected. While there is no reliable way of checking how treatment has affected your fertility, these tests provide your fertility specialist or reproductive endocrinologist with some information. You can ask them how much the tests will cost.

Blood tests

You may have a variety of blood tests.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) – This can measure the hormone FSH, which may indicate how close to menopause you are. This hormone is produced by the pituitary gland in the brain, and stimulates the follicles in the ovaries, which will in turn release eggs. FSH levels need to be measured on specific days of the menstrual cycle – usually the first 2–4 days – as levels change throughout the month.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) – This measures the hormone AMH, which is released by the developing eggs in the follicles. The level of AMH in the blood is an estimate of the number of eggs left in the ovaries. A high level of AMH may mean you have more eggs. It does not reflect egg quality or the ability to have a baby. AMH is usually low after cancer treatment but may increase once you’ve recovered from chemotherapy. If it remains low or unmeasurable after chemotherapy for breast cancer, this is a sign menopause is permanent.

Oestrogen (oestradiol) – This is produced mainly in the ovaries. The level of oestradiol rises and falls throughout the menstrual cycle, so a single measurement does not give good information about fertility.

Luteinising hormone (LH) – This hormone helps the ovaries release an egg. High levels of LH may be a sign that your ovaries have stopped working (premature ovarian insufficiency or POI.

Ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasound – An ultrasound uses echoes from soundwaves to create a picture of the cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. A technician will insert an ultrasound wand, which is covered with a disposable plastic sheath and gel, into the vagina. A scan of the abdomen is an option for younger people.

Antral follicle count (AFC) – An ultrasound wand is inserted into the vagina to show the number of follicles in the ovaries. Each follicle contains a single immature egg.

Natural conception

You may be able to conceive naturally after finishing cancer treatment if your ovaries are still releasing eggs and you have a uterus. If fertility tests suggest it may be possible for you to get pregnant, your medical team will encourage you to try for a baby naturally.

Even if your periods return after chemotherapy or pelvic radiation therapy, there is a high risk of early menopause. If menopause is permanent, you will no longer be able to conceive naturally.

Uterus transplant is being studied in clinical trials. Talk to your doctor about the latest research and whether there are any suitable clinical trials for you.

Donor eggs and embryos

If after cancer treatment you have early menopause but a healthy uterus, you could try for a pregnancy using eggs or embryos donated by another person. You may be able to use eggs or embryos from overseas, but there are strict rules about importing them into Australia. Donors cannot be paid but you can cover (reimburse) their medical expenses.

Using donor eggs

In most cases, eggs are donated by a family member or friend. Your fertility clinic may have an egg bank, but there is usually a long waiting list. All donors are required to have blood tests, answer questions about their genetic and medical information, and have counselling.

After the eggs are collected from the donor, they are combined with sperm from your partner or a donor using IVF. The embryo is frozen until needed.

Using donor embryos

Donor embryos usually come from people who still have frozen embryos after they’ve had successful IVF treatment. Embryos may be donated for ethical reasons (instead of discarding the embryos) or compassionate reasons (to help someone with infertility).

If you use a donated embryo, you will take hormones to prepare your uterus for pregnancy. When your body is ready, the embryo will be thawed and implanted into your uterus using IVF. A child born from a donated embryo is deemed to be the child of the birth mother. Donors have no legal or financial obligation to the child. It is common to have counselling before beginning the IVF process.

Finding information about the donor

In Australia, fertility clinics can only use eggs and embryos from donors who agree (consent) that people born from their donation can find out who they are. This means that the donor’s name, address and date of birth are recorded.

Once donor-conceived people turn 18, they are entitled to access identifying information about the donor.

In some states, a central register is used to record details about donors and their donor-conceived offspring. Parents of donor-conceived children, and donor-conceived people who are over the age of 18, can apply for information about the donor through these registers. In other states and territories, people who want information about their donor can ask the clinic where they had treatment.

It is important to discuss possible issues for donor-conceived children with a fertility counsellor.

Male options before cancer treatment

This section has information about ways you can preserve your fertility before starting cancer treatment. It’s ideal to discuss the options with your cancer or fertility specialist at this time.

Sperm banking (cryopreservation) and radiation shielding are well-established ways to preserve fertility. Surgically extracting sperm from the testicles is another way to store sperm for later use. The option that is right for you depends on the type of cancer you have and your personal preferences.

Keep in mind that no method works all of the time. Fertility treatments carry some risks and your doctor should discuss these before you go home.

If you didn’t have an opportunity to discuss your options before starting cancer treatment, you can still consider your fertility later. Your choices after treatment will depend on whether you are able to produce sperm.

Learn more about the options below.

Banking sperm or freezing sperm (cryopreservation)

What this is

- collecting, freezing and storing sperm

- this is the standard way of preserving fertility in males

When this is used

- when you want to store sperm for the future

- samples can be stored for up to 20 years

- legal limits on how long sperm can be stored are different in each state and territory; it’s possible to ask for an extension

- your fertility clinic can advise about time limits and the cost of storage

How this works

- the procedure is performed in hospital or in a sperm bank facility (also called an andrology unit)

- samples are collected in a private room where you can masturbate or have a partner sexually stimulate you, and then ejaculate into a jar

- it’s recommended that you provide 2–3 samples; you may need to visit the clinic more than once to make sure enough semen is collected

- sperm is then frozen until needed

- when you are ready to have a child, the frozen sperm is thawed and used to fertilise an egg using IVF

What to consider

- if you collect semen at home, you must keep the sample close to body temperature and get it to the sperm bank facility within an hour

- if you want to collect semen during sex, you must use a special condom you can get from the sperm bank facility

- if you are unable to ejaculate, there are medical ways to encourage ejaculation

- if you are unable to produce a sample of semen, sperm may be collected using testicular sperm extraction

- you may feel nervous and embarrassed going to a sperm bank, or worry whether you will be able to ejaculate; the medical staff are used to these situations; you can also bring someone with you

Radiation shielding

What this is

- protecting the testicles from external beam radiation therapy with a shield

When this is used

- if the testicles are close to where radiation beams are directed (but are not the target of the radiation), they can be protected from the radiation beams

How this works

- protective lead coverings called shields are used

What to consider

- this technique does not guarantee that radiation will not affect the testicles, but it does provide some level of protection

Testicular sperm extraction (TESE)

What this is

- a way of looking for sperm inside the testicular tissue

- also called surgical sperm retrieval

When this is used

- when you can’t ejaculate

- when there is not enough sperm in the semen sample

- to collect sperm from men with retrograde ejaculation

How this works

- under anaesthetic, a fine needle is inserted into the epididymis or testicle to find and extract sperm; this is called testicular aspiration

- if no sperm is found, your specialist may do an open biopsy to retrieve a larger tissue sample

- collected sperm is frozen and can later be used to fertilise eggs during IVF

What to consider

- in rare cases, no sperm is found in the testicular tissue

Male options after cancer treatment

After cancer treatment, your medical team will look at a sample of your semen to assess how many sperm you are making, how healthy they look and how well they move (motility).

Depending on the results of these tests, your options include:

- conceiving naturally

- intrauterine insemination or IUI

- artificial insemination or IVF using your own sperm frozen before treatment or fresh sperm collected after treatment

- testicular sperm extraction, if you can’t ejaculate normally or there is no sperm in the semen

- banking sperm after treatment ends, if you are still fertile

- using donor sperm.

Checking fertility after treatment

After treatment, you may be able to have an erection and ejaculate, but this doesn’t necessarily mean you are fertile. Before trying to conceive, you may want to do some tests to see how your fertility has been affected. These can be arranged by your fertility specialist or reproductive endocrinologist. The results will help the specialist recommend the best options for having a child after cancer treatment.

If you stored sperm in a sperm bank before cancer treatment, your doctor can compare this sample to your sperm sample after treatment.

Learn more about the tests you might have below.

Semen analysis (sperm count)

This test can show if you are producing sperm and, if so, how many there are, how healthy they look and how active they are. You will go into a private room and masturbate until you ejaculate into a small container. The semen sample is sent to a laboratory for analysis. The results will help the fertility specialist determine whether you are likely to need help to conceive.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

A blood test can measure levels of FSH. This hormone is produced by the pituitary gland in the brain. In males, FSH controls sperm production.

If FSH levels are higher than normal, this is a sign that fewer sperm are being produced. If FSH levels are lower than normal, this indicates that the pituitary gland is damaged. This will affect the number of sperm produced. This does not necessarily mean that sperm production is too low for a pregnancy, but it is a sign that fertility may have been affected.

Luteinising hormone (LH) and testosterone

A blood test can measure LH and testosterone levels. LH is important in fertility, because it:

- maintains the amount of testosterone that is produced by the testicles

- helps with sperm production

- promotes muscle strength

- boosts general sexual health including sex drive (libido).

Like many hormones in the body, LH and testosterone levels can vary depending on the time of the day. They are highest in the morning, so the test is done earlier in the day. It is important to tell your doctor whether or not you’ve been using marijuana, as this will lower LH and testosterone levels.

Natural conception

You may be able to get your partner pregnant naturally after finishing cancer treatment. This will only be possible if your semen production returns to normal and you are making healthy, active sperm. As fertility declines with age, it will also depend on the age of you and your partner. If treatment has permanently affected your ability to produce sperm and have erections, you will no longer be able to conceive naturally.

Your medical team will do tests to assess your fertility and check your general health. Depending on the treatment you’ve had, they may advise you to wait 6 months to 2 years before trying to conceive. Discuss the timing and contraception options with your specialist.

The pituitary gland makes hormones that tell the testicles to make sperm. If cancer treatment has damaged the pituitary gland, you may be able to have medical treatment to trigger the production of sperm. This is called sperm induction.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI)

Also called artificial insemination, this technique places the sperm directly into the uterus. IUI increases the chance that the sperm will fertilise an egg. The sperm may be fresh or it may have been frozen. The sample is washed and faster-moving sperm are separated from slower sperm.

Insemination is usually done in a fertility clinic. Once your partner is ovulating, the sperm are inserted into their uterus using a small, soft tube (catheter). This takes only a few minutes and may cause some mild discomfort to your partner. You should know in a few weeks whether fertilisation took place.

In-vitro fertilisation (IVF)

IVF uses either sperm collected and frozen before treatment or fresh sperm to fertilise an egg outside of the body. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is a specialised type of IVF in which a single, good quality sperm is injected into an egg.

Donor sperm

If you are infertile after cancer treatment, you could try for a pregnancy using sperm donated by another person.

Using donor sperm

In most cases, sperm are donated by a family member or friend. Your fertility clinic may have access to donor sperm, but there is usually a waiting list. You may be able to advertise for your own donor. It’s possible to use sperm from overseas, but there are strict rules about importing donor sperm into Australia.

Sperm donors have voluntarily contributed sperm to a fertility clinic. They are not paid for their donation, but you can cover (reimburse) their travel or medical expenses. The donors are usually aged 21–45. Some states and territories may have a limit on how many people can have children from the same sperm donor. The limit includes the donor’s partner. Ask your fertility clinic for more information.

All donors are required to complete health tests, answer questions about their genetic and medical information and have counselling.

Personal information is also collected, including details about ethnicity, education, hobbies, skills and occupation.

Samples are screened for genetic diseases or abnormalities, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and overall quality, then quarantined for several months. Before the sperm is cleared for use, the donor is checked again for infectious diseases.

The sperm is frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen in individual containers. When the sperm is ready to be used, insemination is usually done in a fertility clinic. The sample is thawed to room temperature and inserted directly into the uterus using IUI or combined with an egg using IVF.

Finding information about the donor

In Australia, fertility clinics can only use sperm from donors who agree that people born from their donation can find out who they are. This means that the donor’s name, address and date of birth are recorded.

All donor-conceived people are entitled to get identifying information about the donor once they turn 18.

In some states, details about donors and their donor-conceived offspring are recorded on a central register. Parents of donor-conceived children, and donor-conceived people who are over the age of 18, can apply for information about the donor through these registers. In other states and territories, people who want information about their donor can ask the clinic where they had treatment.

It is important to discuss possible issues for donor-conceived children with a fertility counsellor.

Preserving fertility in children and adolescents

When a child or adolescent is diagnosed with cancer, there are many issues to consider. Often the focus is on survival, so health professionals and families may not immediately think about fertility. Many young people say that fertility is important to them.

Some cancer treatments do not affect a child’s reproductive system. Others can damage the ovaries, which contain eggs, or the testicles, which make sperm. Sometimes this damage is temporary, but sometimes it’s permanent.

In many cases, decisions about fertility preservation are made before treatment begins. Often the decision involves specialists, the young person and their parents or carers. Parents of children under 18 will usually need to consent to any fertility preservation procedures.

The National Ovarian and Testicular Tissue Transport and Cryopreservation Service allows young people to have their ovarian or testicular tissue harvested by their own fertility specialist and then transported and stored at the national cryobank at The Royal Women’s Hospital (Melbourne).

Ways to preserve fertility in young females

The options will depend on whether the young person has been through puberty. Most young females go through puberty between the ages of 8 and 13.

Before puberty

- Ovarian tissue that contains immature eggs can be removed and frozen for later use. This is called ovarian cryopreservation.

- When needed, the tissue is put back into the body. There have been several births worldwide from ovarian tissue removed before puberty and it is no longer considered experimental.

After puberty

- Mature eggs or ovarian tissue can be collected and frozen (cryopreservation) for later use.

- Taking a long-acting hormone called gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) may reduce activity in the ovaries or ovarian tissue and protect eggs from damage during cancer treatment for breast cancer.

- Hormone levels can be checked to assess fertility. Having periods after treatment is not a sign of fertility.

Before or after puberty

- Shielding the abdominal area during radiation therapy to the pelvic area provides some level of protection to the ovaries but not the uterus.

- Surgically move the ovaries away from the field of radiation (ovarian transposition). If the ovaries aren’t protected, the risk of ovarian failure is higher (premature ovarian insufficiency).

Ways to preserve fertility in young males

The options will depend on whether the young person has been through puberty. Most young males go through puberty between the ages of 9 and 14. After puberty, semen contains mature sperm.

Before puberty

- There are no proven fertility preservation methods for young males who have not gone through puberty.

- Freezing testicular tissue (testicular tissue cryopreservation) is being tested with young boys at high risk of infertility. Tissue that contains cells that make sperm is removed from the testicles through a small cut. This technique is not widely available and is still considered experimental.

After puberty

- Mature sperm can be collected, frozen and stored (cryopreservation) for later use with IVF. This is known as sperm banking.

- Sperm cells can be removed from the testicles (testicular sperm extraction), which are frozen and stored for later use with IVF. This technique is not widely available.

- You can have a semen analysis and various blood tests to assess fertility. Having erections and ejaculating are not signs of fertility.

Before or after puberty

- Testicular shielding involves placing a protective lead covering over the pelvis area during radiation therapy. This provides some level of protection. If this area is not protected, sperm production may be affected, which could cause infertility.

Other ways to be a parent

Giving birth yourself or having your partner become pregnant aren’t the only ways to become a parent. This chapter talks about other paths to parenthood you may want to consider, including surrogacy, adoption and fostering.

Surrogacy

Surrogacy may be an option if you are unable or do not wish to carry a pregnancy. For example, you may choose a surrogate to carry your embryo if you do not have a uterus or you have been advised that it is medically too risky to carry a pregnancy.

In Australia, a surrogate is a healthy female who carries a donated embryo to term. The surrogate cannot use her own eggs. The intended parents or a donor provide the egg and sperm to create an embryo. This embryo is implanted into the uterus of the surrogate through IVF.

Advertising for someone to be a surrogate or to pay a surrogate for their services is illegal in Australia. Non-commercial or altruistic surrogacy is legal. It’s common for people to ask someone they know to be the surrogate. You can cover the surrogate’s medical costs and other reasonable expenses.

Surrogacy is a complex process. The fertility clinic organising it ensures that both the donor and surrogate go through counselling and psychiatric testing before the process begins. An ethics committee may also have to approve your case. This ensures that everyone involved makes a well-informed decision. For detailed information about surrogacy, including a helpful domestic surrogacy arrangement legal checklist, visit the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority.

Paid surrogacy is legal in some countries overseas. However, in some Australian states and territories it is a criminal offence for residents to enter into commercial surrogacy arrangements overseas – you will need to check that it is legal in your state or territory. It is also important to seek independent legal advice about parentage, citizenship and any conditions you and the surrogate have to meet. To find out more about international surrogacy, visit Smartraveller.

This is general information about surrogacy. Laws regulating surrogacy vary across Australia and may change. Check with your local fertility clinic or legal adviser for the current legislation in your state or territory. It’s best to consult a lawyer before making a surrogacy arrangement.

Adoption and fostering

Adoption involves becoming the legal parent of a child who is not biologically yours and looking after them permanently. Although the number of adoptions in Australia each year is low, you may be able to adopt a child within Australia or from an overseas country.

Fostering (foster care) means taking responsibility for a child without becoming the legal parent. Types of foster care include emergency, respite, short-term and long-term care. In Australia, there are more opportunities to foster than to adopt.

Most adoption and fostering agencies say they do not rule out adoption or fostering for cancer survivors based on their medical history. However, all applicants must declare their health status. The agency may also speak directly with your doctor and require you to have a medical examination. The intention is to determine the risk of the cancer returning and your capacity to raise a child.

Applicants for adoption and fostering must also be willing to meet other criteria. The agency from your state or territory may send a representative to assess your home, and you will have a criminal record (background) check. The process depends on where you live and if the child is from Australia or overseas.

For more information about adoption and foster care, visit the family and community service government website in your state or territory. Intercountry Adoption Australia is an information and referral service to help guide people through the overseas adoption process. For details, visit their website or call them on 1800 197 760.

Not having a child

If you have not been able to preserve your fertility, or even if you have, you may come to accept that you won’t have a child. You might feel like you ran out of time, money or energy to keep trying to have a child. Not being able to have a child after cancer treatment may cause a range of emotions, including:

- sadness or emptiness

- a sense of grief or loss

- anger that cancer and its treatment caused changes to your body

- relief, contentment or happiness

- empowerment, if you chose not to have children.

You may feel a sense of loss for the life you thought you would have. It can take time to accept that you won’t have a child and learn to enjoy the benefits of being child-free – more time to follow other aspects of your life, focus on your relationships, advance your career or afford a different lifestyle. Many people have happy and fulfilling lives without children, or gain satisfaction from other types of nurturing.

How you feel about having a child may change over time. It may depend on if you have a partner and how they feel. If you want support, a counsellor, social worker or psychologist can talk to you about being child-free and help you deal with challenging situations (for example, if your partner feels differently to you).

Emotional impact

How people respond to infertility varies. Common reactions include shock at the diagnosis and its impact on fertility, grief and loss of future plans, anger or depression from disruption of life plans, uncertainty about the future, loss of control over life direction, and worry about the potential effects of early menopause (such as reduced bone density).

The physical and emotional process of infertility treatment, and not knowing if it will work, can be exhausting. People who didn’t get a chance to think about their fertility until treatment was over say that the emotions can be especially strong.

While these feelings are a natural reaction to loss of fertility, see below for ways to manage these feelings before they overwhelm you. It may also help to consider other ways of becoming a parent, or you may decide to stop trying to have a child.

Coping strategies

Learning that cancer treatment has affected your ability to have children can be challenging. There is no right or wrong way of coping. The strategies described here may help you feel a greater sense of control and confidence.

Gather information – The impact of cancer on your fertility may change your plans or make them unpredictable. Knowing your options for building a family may help you deal with feelings of uncertainty.

Get support from others – Talking to people who have been in a similar situation or to family and friends can reduce feelings of isolation and help you cope. Consider joining a support group for people with cancer or fertility-related issues

Consider professional counselling – You can talk to a counsellor about the impact of infertility. Most fertility units have a fertility counsellor or you can find a private fertility counsellor near you at Access Australia.

Get creative – If you don’t want to talk about how you are feeling, you could keep a journal or blog, or you could make music, draw, paint or craft. You can share your writing or artworks with those close to you or keep them private.

Try relaxation and meditation exercises – Both of these techniques can help reduce stress and anxiety. Exercise such as walking can also help with mood changes and energy levels.

Relationships and sexuality

A cancer diagnosis, treatment side effects and living with the uncertainty of infertility may affect how you feel about your relationships and your sense of who you are and how you see yourself (sexuality).

Whether or not you have a partner, it may be a good idea to find out your fertility status as soon as you feel ready. This way, you can think about what you want, and if you have a partner, start talking with them about what the future may hold.

Communicating with your partner

A cancer diagnosis, infertility and changes to your sexuality can cause tension in a relationship.

Your partner will also experience a range of emotions, which may include helplessness, frustration, fear, anger and sadness. How your relationship is affected may depend on how long you have been together, expectations about becoming a parent, the strength of your relationship before cancer and infertility, and how well you communicate.

Fertility issues may cause conflict between partners. Some partners are very supportive, while others avoid talking about it. If your partner is unwilling to talk about fertility, you might feel like you’re coping alone or making all the decisions. It can also be challenging if you and your partner disagree about what to do and focus on different outcomes. Seeing a fertility counsellor can help you talk about these issues and develop strategies to manage conflict.

Communicating with a new partner

If you are in a new relationship, you may be worried about their reaction to your diagnosis, or explaining any fertility concerns.

While the timing will be different for each person, it can be helpful to wait until you and your new partner have developed a mutual level of trust and caring. Start the conversation when you feel ready. It may be easier if you practise what you want to say – and how you would respond to questions your partner may ask – with a friend, family member or health professional.

Sexuality and intimacy

Sexuality is about who you are, how you see yourself, how you express yourself sexually and your sexual feelings for others. Being able to conceive a child may be part of your identity, and infertility may change how you feel about yourself. This can happen if you are in a heterosexual relationship, if you are LGBTQI+ or have a same-gender partner. You may feel that sex is linked with the stress of infertility, and you may lose interest in intimacy and sex (low libido).

Body image – Fertility concerns may affect how you feel about your body (body image). You may feel that your body has “let you down”. It will take time to accept any physical and emotional changes. It may be helpful to:

- look after your body with exercise, eating well and sleep

- spend time with a partner doing something you both enjoy.

Resuming sexual activity after cancer treatment – Some cancer treatments may cause physical problems, such as pain during penetrative sex or trouble getting and keeping an erection.

These problems may be difficult for you and your partner, if you have one, but can be managed in various ways:

- think about what used to get you sexually aroused and explore if it still does

- explore different erogenous zones; mutual masturbation; oral sex; personal lubricants; vibrators and other sex toys; erotic images and stories

- focus on getting in the mood and making foreplay enjoyable to take the pressure off getting pregnant

- talk to each other about how fertility concerns are affecting you and discuss ways you can keep enjoying sex (e.g. “I just want to cuddle now” or “That feels good”).

If you feel you need further support, consider talking to a counsellor or sex therapist. To find a counsellor in your local area, speak to your doctor or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

If you’re a young adult

During and after treatment for cancer, young people continue to develop and mature. This means living life as normally as possible, which may include going on dates and having a partner. You may feel confused about how much to share with others about having cancer and the impact on your fertility.

Canteen supports young people aged 12–25 who have been affected by cancer. They offer counselling in person or by phone, email or direct messaging (DM). Canteen also runs online forums and camps. To get in touch, call

1800 835 932 or visit Canteen.

This information was last reviewed October 2022 by the following expert content reviewers:

Prof Martha Hickey, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Melbourne and Director, Gynaecology Research Centre, The Royal Women’s Hospital, VIC; Dr Sally Baron-Hay, Medical Oncologist, Royal North Shore Hospital and Northern Cancer Institute, NSW; Anita Cox, Cancer Nurse Specialist and Youth Cancer Clinical Nurse Consultant, Gold Coast University Hospital, QLD; Kate Cox, McGrath Breast Health Nurse Consultant, Gawler/ Barossa Region, SA; Jade Harkin, Consumer; A/Prof Yasmin Jayasinghe, Director Oncofertility Program, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Chair, Australian New Zealand Consortium in Paediatric and Adolescent Oncofertility, Senior Research Fellow, The Royal Women’s Hospital and The University Of Melbourne, VIC; Melissa Jones, Nurse Consultant, Youth Cancer Service SA/NT, Royal Adelaide Hospital, SA; Dr Shanna Logan, Clinical Psychologist, The Hummingbird Centre, Newcastle West, NSW; Stephen Page, Family Law Accredited Specialist and Director, Page Provan, QLD; Dr Michelle Peate, Program Leader, Psychosocial Health and Wellbeing Research (emPoWeR) Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Royal Women’s Hospital and The University of Melbourne, VIC; Pampa Ray, Consumer; Prof Jane Ussher, Chair, Women’s Health Psychology, and Chief Investigator, Out with Cancer study, Western Sydney University, NSW; Prof Beverley Vollenhoven AM, Carl Wood Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Monash University and Director, Gynaecology and Research, Women’s and Newborn, Monash Health and Monash IVF, VIC; Lesley Woods, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA.