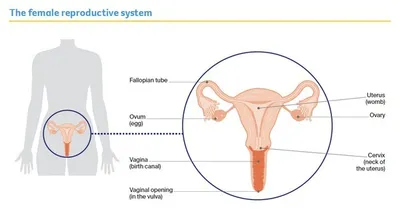

The vagina

Sometimes called the birth canal, the vagina is a muscular tube about 7–10 cm long that extends from the cervix to the vulva (external genitals).

The vaginal opening is where menstrual blood flows out of the body during a period, sexual intercourse occurs, and a baby leaves the body.

The vagina is part of the female reproductive system, which also includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vulva.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about vaginal cancer are below.

What is vaginal cancer?

Cancer in the vagina can be either a primary or secondary cancer. The two types of cancer are different and are often treated differently.

Primary vaginal cancer – This is cancer that starts in the vagina.

This information is only about primary vaginal cancer.

Secondary vaginal cancer – This is cancer that has spread (metastasised) to the vagina from a primary cancer in another part of the body, such as the cervix, uterus, vulva, bladder or bowel. Secondary vaginal cancer is much more common than primary vaginal cancer.

For information about secondary vaginal cancer, see the Cancer Council booklet about the primary cancer and speak to your treatment team.

What are the main types of primary vaginal cancer?

The 2 main types of primary vaginal cancer are named after the cells they start in.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

- starts in thin, flat (squamous) skin cells lining the vagina

- most common type (about 9 out of 10 cases)

Adenocarcinoma

- develops from the mucus producing (glandular) cells in the vagina

- includes clear cell carcinoma

- less common type (less than 1 out of 10 cases)

There are also rarer types of vaginal cancer. These include melanomas, which start in skin cells called melanocytes; sarcomas, which start in the muscle; and lymphomas, which start in the white blood cells.

Precancerous vaginal cell changes

Sometimes the squamous cells in the lining of the vagina start to change. These changes may be precancerous. This means there is an area of abnormal tissue (a lesion) in the vagina that is not cancer, but may develop into cancer over time if left untreated.

These lesions are called squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL), which used to be known as vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). Lesions can be classified as either:

- low grade (LSIL), which may go away without treatment

- high grade (HSIL), which may develop into vaginal cancer if left untreated.

SIL usually has no symptoms and is often caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Most cases of SIL don’t develop into vaginal cancer. Your doctor will explain the treatment options suitable for you.

How common is vaginal cancer?

Vaginal cancer is one of the rarest types of cancer affecting the female reproductive system (gynaecological cancer). About 120 women are diagnosed with vaginal cancer each year in Australia.

Anyone with a vagina can get vaginal cancer – women, transgender men, non-binary people and intersex people. For more information, speak to your doctor or see our ‘LGBTQI+ People and Cancer’ booklet.

What are the risk factors?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) – Many cases of vaginal cancer are caused by infection with HPV, which is a very common virus in people who are sexually active. About 4 out of 5 people will become infected with one type of genital HPV at some time in their lives. HPV often causes no symptoms. Only some types of HPV cause cancer, and most people with HPV don’t develop vaginal or any other type of cancer. It can be many years between infection with HPV and the first signs of HSIL or vaginal cancer.

Other risk factors – Although HPV infection and vaginal HSIL are the main risk factors, other things that increase the risk include:

- previously having HSIL of the cervix or cervical cancer

- smoking tobacco (which can make cancer more likely to develop in people with HPV)

- being aged over 70 (almost half of all vaginal cancers are in women over 70)

- having a weakened immune system

- exposure to a drug called diethylstilbestrol (DES), which was prescribed to pregnant women from the 1940s to the early 1970s to prevent miscarriage. The female children of women who took DES have a small but increased risk of developing clear cell carcinoma of the vagina.

What are the symptoms?

Early vaginal cancer often has no obvious symptoms. The cancer is sometimes found by a routine cervical screening test. If symptoms do occur, they most often include:

- bloody vaginal discharge (not related to your menstrual period)

- pain during sexual intercourse

- bleeding after sexual intercourse

- a lump in the vagina.

Rarer symptoms include pain in the pelvic area or rectum; and bladder problems, such as blood in the urine (wee) or passing urine often or during the night.

Not everyone with these symptoms has vaginal cancer. If you have any ongoing symptoms, make an appointment to see your general practitioner (GP). Don’t let embarrassment stop you getting checked.

How is vaginal cancer diagnosed?

You are likely to have some of the following tests.

Physical examination

Your doctor will look at your vagina, groin and pelvic area. They may use an instrument called a speculum to separate the vaginal walls so they can check the vagina and cervix for cancer.

Cervical screening test

This test looks for cancer-causing types of HPV in a sample of cells taken from the cervix or vagina. During the physical examination, the doctor uses a small brush or swab to remove some cells from the surface of the cervix. This test replaced the Pap test in 2017.

Colposcopy

This uses a magnifying instrument called a colposcope to look at the vulva, vagina and cervix and see if there are any abnormal or changed cells. The colposcope is placed near your vulva but does not enter your body.

Biopsy

During a colposcopy, your doctor will usually take a small tissue sample (biopsy) from the vaginal area. If you have a condition that has narrowed the vagina, you may need to have a biopsy under general anaesthetic. The tissue sample will be sent to a laboratory for testing. A biopsy is the best way to diagnose vaginal cancer.

Imaging scans

If vaginal cancer is found, you may have one or more imaging scans to check if the cancer has spread to other parts of your body. These scans may include a chest x-ray, MRI or PET–CT scan.

To find out more about these scans, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Staging vaginal cancer

Staging describes the size of the cancer and how far it has spread. Knowing the stage helps doctors recommend the best treatment for you.

Stage 1 - Cancer is found only on the vaginal surface; no spread to lymph nodes.

Stage 2 - Cancer has spread through the vaginal wall; no spread into the wall of the pelvis or to the lymph nodes.

Stage 3 - Cancer has spread to the walls of the pelvis, lower part of the vagina, or is blocking the urinary tract; may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 4 - Cancer has spread to the bladder, rectum, or more distant parts of the body, such as the lungs or bone; may have spread to lymph nodes.

What are lymph nodes?

Lymph nodes are part of your body’s lymphatic (drainage) system. The lymphatic system is a network of vessels, tissues and organs that helps to protect the body against disease and infection. There are large groups of lymph nodes in the neck, armpits and groin. Sometimes vaginal cancer can travel through the lymphatic system to other parts of the body. To work out if the vaginal cancer has spread, your doctor may check the lymph nodes.

Treatment for vaginal cancer

Because vaginal cancer is rare, it is recommended that you are treated in a specialist centre for gynaecological cancer.

If you have to travel for treatment, there may be a program in your state or territory to refund some of the cost of travel and accommodation. The hospital social worker can help you apply or you can call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

The multidisciplinary treatment (MDT) team may include a radiation oncologist, surgeon (usually a gynaecological oncologist), medical oncologist, specialist nurses, and allied health professionals, such as an exercise physiologist or social worker.

The treatment recommended by your doctor will depend on the results of your tests, the type of cancer, where the cancer is, whether it has spread, your age and your general health.

Understanding the disease, the available treatments, possible side effects and any extra costs can help you weigh up the treatment options and make a well-informed decision. You may want to get a second opinion from another specialist to confirm or explain the treatment options.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, this treatment uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is usually from x-ray beams.

Radiation therapy is the main treatment for vaginal cancer because vaginal cancer that is close to the urethra, bladder and rectum is often difficult to remove surgically. You may have radiation therapy on its own or combined to have both types to treat vaginal cancer. Your radiation oncologist will recommend the course of treatment most suitable for you, and explain what to expect and possible side effects.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

In EBRT, a machine precisely directs radiation beams from outside the body to the affected areas of the pelvis. You will lie on a treatment table under the radiation machine. Each treatment session takes around 10–15 minutes and is painless.

EBRT for vaginal cancer is usually given daily, Monday to Friday, over 4–6 weeks. The exact number of treatment sessions you have will depend on the type and size of the cancer, and whether it has spread to the lymph nodes.

Internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy)

Brachytherapy delivers radiation directly to the tumour from inside your body. It is usually given after you have finished having EBRT. Brachytherapy uses a small amount of radioactive material, called a source, to deliver the radiation. There are different ways to have brachytherapy, depending on the size of the cancer after EBRT.

After brachytherapy, you may feel uncomfortable in the vaginal region. Pain medicines can help if needed. You may have some vaginal discharge or bleeding for a few days. To reduce the risk of infection, use sanitary pads, not tampons.

Intracavity brachytherapy

Used for – small tumours that only involve a thin layer of vaginal tissue

Where done – usually given during day visits to a hospital or treatment centre as an outpatient

How done

- a device called an applicator is placed inside the vagina

- the applicator may be a standard cylinder shape, with a rounded tip, or custom moulded to your vagina

- one or more tubes inside the applicator are connected to a machine that delivers the radiation

- inserting the applicator may make your vagina feel stretched and uncomfortable

- you may have pain medicine or a local anaesthetic to make it more comfortable

How long

- you may need 3–4 treatment sessions

- each session takes 20–30 minutes

- the applicator is taken out after each session and then you can go home

Interstitial brachytherapy

Used for – cancers that are still quite thick after you have finished having EBRT

Where done – you will be admitted to hospital; not provided at all hospitals so you may have to travel for treatment

How done –

- under general anaesthetic, needles and tubes (brachytherapy catheters) are inserted in and around the remaining cancer; other applicators may also be used to help deliver the radiation

- the radiation source travels through the needles to the cancer

- the needles may need to stay in place for 2–3 days and you must lie flat on your back until the needles are removed

- you will be given pain medicine

- you will have a tube called a urinary catheter to drain urine from your bladder as you will not be able to get up to go to the toilet

How long –

- you may need 3–4 treatments, delivered at least 6 hours apart

- another treatment schedule involves hourly treatments

Common treatment side effects

Let your treatment team know about any symptoms or side effects you have. They may be able to suggest ways to reduce or manage any discomfort.

Possible side effects from radiation therapy – fatigue; skin reactions (dry, itchy and tender skin, peeling skin); changes to the vagina (dryness, shortening, narrowing); bladder and bowel changes; menopause; urinary incontinence or having to urinate more often; lymphoedema; sexual problems.

Surgery

Surgery may be used for small cancers found in the lining of the vagina. A gynaecological oncologist will try to remove all of the cancer along with some of the surrounding healthy tissue (called a margin). Some lymph nodes in your pelvis or groin may also be removed, depending on the stage of the cancer.

There are several different operations for vaginal cancer. The type of surgery recommended for you depends on the location of the tumour and how far it has spread. Your gynaecological oncologist will talk to you about the risks and complications of your surgery, as well as possible side effects.

Types of vaginal surgery

- Wide local excision (partial vaginectomy) – The surgeon cuts out the cancer and a margin. Only the affected part of the vagina is removed.

- Total vaginectomy – The whole vagina is removed.

- Radical vaginectomy – The whole vagina and surrounding tissue are removed.

- Hysterectomy – The uterus and cervix are removed. Your gynaecological oncologist will let you know if it is also necessary to remove your ovaries and fallopian tubes. If you are premenopausal, removing your ovaries will bring on menopause.

- Lymph node surgery – Lymph nodes in the pelvis or groin may be removed to check for the spread of cancer. This is called a lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection).

- Reconstructive surgery – If the entire vagina is removed, in some cases a reconstructive (plastic) surgeon can make a new vagina using skin and muscle from other parts of your body. This is called vaginal reconstruction or formation of a neovagina.

Recovery after surgery

Your recovery time will depend on the type of surgery you had and your general health. It is common to be in hospital for a few days to a week.

You will be given pain medicine to control any pain. Do not put anything into your vagina after surgery until your doctor says the area is healed (usually 6–8 weeks). This includes tampons and menstrual cups. You can expect some light vaginal bleeding, which should stop within 2 weeks.

Taking care of yourself at home

You will be given advice about a range of issues before you go home. The following information is a general overview of what to expect.

- Wound care – Your doctors and nurse will give you instructions about how to look after the wound. If there is any redness, swelling, wound discharge or unusual smell, contact your doctor.

- Rest – You will need to take things easy and get plenty of rest in the first week. Avoid sitting for long periods of time if it is uncomfortable, or try sitting on a pillow or 2 rolled towels placed under the buttocks.

- Exercise – Check with your treatment team about when you can start doing your regular activities. You may not be able to lift anything heavy, but gentle exercise, such as walking, can help speed up recovery. Because of the risk of infection, avoid swimming until your doctor says you can.

- Emotions – If part of your genital area is removed, you may feel a sense of loss and grief. It may help to talk about how you are coping with someone you trust or seek professional support.

- Sex – Sexual activity needs to be avoided for about 6–8 weeks after surgery, or longer if reconstructive surgery was performed. Ask your doctor when you can restart sexual activity, and explore other ways you and your partner can be intimate.

- Driving – You will need to avoid driving after the surgery until your wound has healed and you are no longer in pain. Discuss this issue with your doctor. Check with your car insurer for any restrictions about driving after surgery.

Common treatment side effects

Let your treatment team know about any symptoms or side effects you have. They may be able to suggest ways to reduce or manage any discomfort.

Possible side effects from surgery – fatigue; scar tissue; difficulty urinating; lymphoedema (if lymph nodes removed); sexual problems; trouble controlling the flow of urine (urinary incontinence); altered urinary stream; bowel changes.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth. It may be used if the vaginal cancer is advanced or returns after treatment. Chemotherapy may be combined with radiation therapy (known as chemoradiation or chemoradiotherapy).

The drugs are usually given by injection into a vein (intravenously). You will usually have several treatment sessions, with rest periods in between. Together, the session and rest period are called a cycle. Treatment is usually given during day visits to a hospital or clinic as an outpatient. Rarely, you may need to stay in hospital for a few nights.

There are many different chemotherapy drugs. The side effects will vary depending on the drugs you are given, the dose and how you respond. Chemotherapy for vaginal cancer may also increase any skin soreness caused by radiation therapy.

Common treatment side effects

Let your treatment team know about any symptoms or side effects you have. They may be able to suggest ways to reduce or manage any discomfort.

Possible side effects from chemotherapy – fatigue; nausea; increased risk of infection.

Managing side effects of treatment for vaginal cancer

All treatments can have side effects.

Some side effects go away quickly; others can take weeks, months or even years to improve. Your treatment team will discuss possible side effects with you before your treatment starts.

Longer-term side effects

Vaginal cancer and its treatment can sometime lead to long-term, life-changing side effects.

Changes to the vulva and vagina – Treatment can change the look and feel of the vulva and vagina. Radiation therapy may make skin in the treatment area dry, itchy and tender. Ask your treatment team about ways to manage these changes. Skin reactions will gradually improve after treatment finishes. Pelvic radiation therapy can narrow the vagina, causing thinning of the walls and dryness. Surgery for vaginal cancer may also make the vagina shorter or narrower. You may be offered vaginal dilators to help keep the vagina open and prevent it from closing over. Dilators may help make sex and follow-up pelvic examinations more comfortable. Ask your doctor, nurse or physiotherapist for more information about using vaginal dilators. They may also suggest using hormone creams or vaginal moisturisers to help with vaginal discomfort and dryness.

Bladder changes – Incontinence is when urine leaks from your bladder without your control. Bladder control may change after surgery or radiation therapy to the vagina. You may find that you need to pass urine more often or feel that you need to go in a hurry, or you may leak a few drops of urine when you cough, sneeze, strain or lift. For ways to manage incontinence, talk to the hospital continence nurse or physiotherapist.

Lymphoedema – If the lymph nodes have been removed during surgery or scarred during radiation therapy, lymph fluid can build up in the tissues under the skin. This is called lymphoedema, and it can cause swelling in the legs, vulva or the area above the vulva covered with pubic hair (mons pubis). Lymphoedema may appear during treatment or months or years late. Not everyone who is at risk will develop it. It is important to seek help as soon as possible, because early diagnosis and treatment can lead to better outcomes. A lymphoedema practitioner can develop a treatment plan for you.

Menopause – If you have not yet been through menopause, radiation therapy for vaginal cancer or having your ovaries removed can cause early menopause. Your periods will stop, and you may have symptoms such as hot flushes, insomnia, dry or itchy skin, mood swings, or loss of interest in sex (low libido). Loss of the hormone oestrogen at menopause may also cause bones to weaken and break more easily (osteoporosis).

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), previously known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), is medicine that replaces the hormones usually produced by the ovaries. It has been shown to treat menopausal symptoms and help prevent osteoporosis. There are also non-hormonal drugs that can help. Talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of MHT, and other ways to deal with the symptoms of menopause.

After menopause, you will not be able to become pregnant. If this is a concern for you, talk to your doctor before starting radiation therapy.

Sex – Whether sexual intercourse is still possible depends on how much tissue was removed from the vagina. Sometimes radiation therapy or surgery to the pelvic area can also affect nerves and tissue in this area, causing scarring, narrowing of the vagina, swelling and soreness. If scar tissue forms around the outside of the vagina, it can narrow the entrance to the vagina, making penetration during sex painful. Using extra lubrication may make sexual activity more comfortable. Choose a water-based or silicone-based gel without perfumes or colouring.

Sexual desire (libido) – Changes to the look and feel of your vagina can cause embarrassment, loss of sexual pleasure, and less interest in sex. The experience of having cancer can also reduce your desire for sex. You may wish to have counselling to help understand the impact treatment has had on your sexuality. A sex therapist or psychologist can help you (and your partner if you have one) adjust to changes and find new ways to express intimacy and enjoy sex. Ask your doctor for a referral.

Dealing with the emotional impact

How you might feel – It is common to feel shocked and upset about having cancer in one of the most intimate areas of your body. It is natural to have a wide variety of emotions, including anger, fear, anxiety, sadness and resentment. Everyone has their own ways of coping – there is no right or wrong way.

Talk to someone – It can help to share how you’re feeling about the diagnosis and treatment side effects with a counsellor or psychologist. Ask your doctor for a referral. For support, you can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Adjusting to changes to your body – Changes to your body can affect your self-image and sense of identity. It takes time to adjust. Try to see yourself as a whole person (body, mind and personality), instead of focusing on the parts that have changed.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment, you will have regular check-ups every 3–12 months for several years to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back and to help you manage any treatment side effects.

Your doctor will talk to you about your follow-up schedule, which will depend on the risk of the cancer coming back. Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Let your doctor know immediately of any health concerns between appointments.

If the cancer comes back

For some people, vaginal cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. Depending on where the cancer recurs, treatment may include surgery, chemoradiation, radiation therapy or chemotherapy. You may also consider joining a clinical trial to try new treatments. For more information, talk to your doctor about suitable trials

or visit Australian Cancer Trials.

In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment.