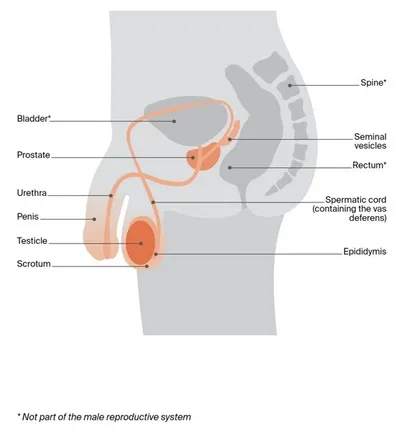

The testicles

The testicles are part of the male reproductive system, which also includes the penis, prostate and a collection of tubes that carry sperm. The testicles are also called testes (or a testis, if referring to one).

What the testicles do – The testicles make and store sperm. They also make the hormone testosterone, which is responsible for the development of male characteristics, such as facial hair, a deeper voice and increased muscle mass, as well as sex drive (libido).

Shape and position in the body – The testicles are 2 small egg‑shaped glands that sit in a loose pouch of skin called the scrotum. The scrotum hangs behind the penis. A tightly coiled tube at the back of each testicle called the epididymis stores immature sperm. The epididymis connects the testicle to the spermatic cord, which contains blood vessels, nerves, lymph vessels and a tube called the vas deferens. The vas deferens carries sperm from the epididymis to the prostate gland.

Ejaculation – When an orgasm occurs, millions of sperm from the testicles move through the vas deferens. The sperm then join with fluids produced by the prostate and seminal vesicles to make semen. Semen is ejaculated from the penis through the urethra during sexual orgasm.

The lymphatic system helps to protect the body against disease and infection. Working like a drainage system, it removes lymph fluid from body tissues back into the blood. It is made up of a network of thin tubes called lymph vessels connected to groups of small, bean-shaped lymph nodes. Usually, lymph fluid from the testicles drains into lymph nodes in the abdomen (belly).

The male reproductive system

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about testicular cancer are below.

What is testicular cancer?

Cancer that develops in the cells of a testicle is called testicular cancer or cancer of the testis (plural: testes). Usually only one testicle is affected, but in some cases both are affected.

As testicular cancer grows, it can spread to lymph nodes in the abdomen or to other parts of the body, such as the bones, lungs or liver.

About 90–95% of testicular cancers start in the cells that develop into sperm – these are known as germ cell tumours. Rarely, germ cell tumours can grow outside the testicles in germ cells found in other parts of the body, such as the brain, middle of the chest and back of the abdomen. These tumours are not testicular cancer and are called extragonadal germ cell tumours. They are treated in a similar way to testicular cancer.

How common is it?

Testicular cancer is not common, but it is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men aged 20–39 (apart from common skin cancers). About 960 men in Australia are diagnosed with testicular cancer each year, which is about 1% of all cancers in men.

Anyone with a testicle can get testicular cancer – men, transgender women, non-binary people and people with intersex variations.

For information specific to you, speak to your doctor and see our information for LGBTQI+ People and Cancer.

What types are there?

The most common testicular cancers are called germ cell tumours. There are 2 main types, seminoma and non-seminoma.

Germ cell tumours

seminoma

- tend to develop more slowly than non-seminoma cancers

- usually occur between the ages of 25 and 45, but can occur at older ages

non-seminoma

- tend to develop more quickly than seminoma cancers

- more common in late teens and early 20s

- there are 4 main subtypes: teratoma, choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumour and embryonal carcinoma

Sometimes a testicular cancer can include a mix of seminoma cells and non-seminoma cells, or a combination of the different subtypes of non-seminoma cells (mixed tumours). When there are seminoma and non-seminoma cells mixed together, doctors treat the cancer as if it were a non-seminoma cancer.

A small number of testicular tumours start in cells that make up the supportive (structural) and hormone-producing tissue of the testicles. These are called stromal tumours. The 2 main types are Sertoli cell tumours and Leydig cell tumours. They are usually benign, and are removed by surgery.

Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS)

Most testicular cancers begin as a condition called germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). This was previously called intratubular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN).

In GCNIS, the cells are abnormal, but they haven’t spread outside the area where the sperm cells develop. GCNIS is not cancer but it may develop into cancer after many years.

GCNIS has similar risk factors to testicular cancer.

It is hard to diagnose because there are no symptoms. Although an ultrasound scan may suggest GCNIS, it can only be diagnosed by testing a tissue sample. This may be through a needle biopsy or surgery to remove the testicle.

Once diagnosed, some cases of GCNIS will be carefully monitored (active surveillance). Other cases will be treated with radiation therapy or surgery to remove the testicle.

Rarely, other types of cancer, such as lymphoma or neuroendrocrine tumours, can also involve the testicles. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

What are the risk factors?

The causes of testicular cancer are largely unknown, but certain factors may increase your risk of developing it. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about any of the following risk factors.

Personal history – Having GCNIS increases the risk of developing testicular cancer. If you have previously had cancer in one testicle, you are also more likely to develop cancer in the other testicle than someone who has not had testicular cancer.

Undescended testicles – Before birth, testicles develop inside the abdomen. By birth, or within the first 6 months of life, the testicles should move down into the scrotum. If the testicles don’t descend by themselves, doctors may perform an operation to bring them down. Although this reduces the risk of developing testicular cancer, people born with undescended testicles are still more likely to develop testicular cancer than those born with descended testicles.

Family history – If your father or brother has had testicular cancer, you are slightly more at risk of developing testicular cancer. But family history is only a factor in a small number (about 2%) of people who are diagnosed with testicular cancer. If you are concerned about your family history of testicular cancer, you can ask your doctor for a referral to a specialist called a urologist.

Infertility – Having difficulty conceiving a baby (infertility) can be associated with testicular cancer.

HIV and AIDS – There is some evidence that people with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) have an increased risk of testicular cancer.

Physical features – Some people are born with an abnormality of the penis called hypospadias. This causes the urethra to open on the underside of the penis, rather than at the end. People with this condition are at an increased risk of developing testicular cancer.

Cannabis use – There is some evidence linking regular cannabis use with the development of testicular cancer.

Intersex variations – The risk of testicular cancer is higher in people with some intersex variations, such as partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, particularly when the testicles remain in the abdomen.

What are the symptoms?

In some people, testicular cancer does not cause any noticeable symptoms, and it may be found during tests for other conditions. When there are symptoms, the most common ones are a lump or swelling in the testicle (often painless) and/or a change in the size or shape of the testicle.

These symptoms don’t necessarily mean you have testicular cancer. They can be caused by other conditions, such as cysts, which are harmless lumps in the scrotum. If you find any lump, however, it’s important to see your doctor for a check-up.

Occasionally, testicular cancer may cause other symptoms such as a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum; a feeling of unevenness between the testicles; a pain or ache in the lower abdomen, testicle or scrotum; enlargement or tenderness of the breast tissue; back pain; or stomach-aches. If you are worried or the symptoms are ongoing, make an appointment to see your doctor.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your general practitioner (GP) will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist called a urologist.

The urologist will arrange further tests. If testicular cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Health professionals you may see

Urologist – treats diseases of the male and female urinary systems and the male reproductive system, including testicular cancer; performs surgery

Anaesthetist – assesses your health before surgery; administers anaesthesia and looks after you during the surgery; commonly plans your pain relief after surgery

Medical Oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy; supports you through regular check‑ups and reviews (active surveillance)

Radiation Oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Fertility Specialist – diagnoses, treats and manages infertility and reproductive hormonal disorders; may be a reproductive endocrinologist or urologist

Cancer Care Coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

Psychologist, Counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Physiotherapist, Occupational Therapist – assist with physical and practical problems, including restoring movement and mobility after treatment

and recommending aids and equipment

How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

Your doctor will usually examine your testicles, scrotum and groin for a lump or swelling.

Some people may find this embarrassing, but doctors are used to doing these examinations and it will only take a few minutes.

If they find a lump that might be testicular cancer, you will have an ultrasound scan, and then you may have a blood test to look for tumour markers. However, a diagnosis of testicular cancer can only be made by removing the testicle for checking (orchidectomy). Most people will have a CT scan before surgery to see if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound uses soundwaves to create a picture of the testicles and scrotum. This is an accurate way to tell the difference between benign fluid-filled cysts and solid tumours. An ultrasound can show if a tumour is present and how large it is.

The person performing the ultrasound will spread a gel over your scrotum and then move a small device called a transducer over the area. This sends out soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or a tumour. A computer turns the soundwaves into a picture. An ultrasound scan is painless and takes about 5–10 minutes.

Blood tests

Samples of your blood will be taken to look for tumour markers and to check your general health by seeing how well your kidneys and other organs are working.

Tumour markers are proteins produced by cancer cells. If your blood test results show an increase in the levels of certain tumour markers, you may have testicular cancer.

Tumour markers and testicular cancer

Raised levels of tumour markers are more common in mixed tumours and non-seminoma cancers. However, it is possible to have raised tumour marker levels due to other causes, such as liver disease or blood disease. Some people with testicular cancer don’t have raised tumour marker levels in their blood.

There are 3 common tumour markers measured for testicular cancer:

- alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) – raised in some non-seminoma cancers

- beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) – raised in some non-seminoma and seminoma cancers

- lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) – raised in some non-seminoma and seminoma cancers.

Doctors will use your tumour marker levels to assess the risk of the cancer coming back after surgery and help them plan your treatment. You will also have regular blood tests to monitor tumour marker levels throughout treatment and as part of follow-up appointments.

Tumour marker levels will drop if your treatment is successful, but they will rise if the cancer is active. If this happens, you may need more treatment.

Surgery to remove the testicle

After doing a physical examination, ultrasound, blood tests and sometimes a CT scan, your urologist may strongly suspect testicular cancer. However, none of these tests can give a definite diagnosis. The only way to be sure of the diagnosis is to surgically remove the affected testicle and examine it in a laboratory. The surgery to remove a testicle is called an orchidectomy or orchiectomy.

For other types of cancer, a doctor can usually make a diagnosis by removing and examining some tissue from the tumour. This is called a biopsy. However, doctors don’t usually biopsy the testicle because there is a small risk that making a cut through the scrotum can cause cancer cells to spread. Rarely, for very select cases, only part of the testicle is removed (partial orchidectomy).

A specialist called a pathologist looks at the removed testicle under a microscope. If cancer cells are found, the pathologist can tell which type of testicular cancer it is and provide more information about the cancer, such as whether and how far it has spread (the stage). This helps doctors plan further treatment.

Removing both testicles – Testicular cancer usually occurs in only one testicle, so it is rare to need both testicles removed. If both testicles are removed, you will no longer produce testosterone and will probably be prescribed testosterone replacement therapy. Having both testicles removed will cause infertility.

Having an orchidectomy

- An orchidectomy is often done to confirm a diagnosis of testicular cancer. It is also the main treatment for testicular cancer.

- You will be given a general anaesthetic to put you to sleep and temporarily block any pain or discomfort during the surgery.

- The urologist will make a cut (incision) in the groin above the pubic bone. This is shown below with a red line.

- The whole testicle is pulled up and out of the scrotum through this cut.

- The spermatic cord is also removed because it contains blood and lymph vessels that may act as a pathway for the cancer to spread to other areas of the body.

- The scrotum is not removed but it will no longer contain a testicle.

- You may choose to have an artificial testicle inserted to keep the shape and give the appearance of a testicle. This is called a prosthesis.

- The operation takes about an hour. You can usually go home the same day, but you may need to stay in hospital overnight.

- You will need someone to take you home and stay with you for 24 hours.

What to expect after an orchidectomy

Your body needs time to heal after the surgery. You will be given advice about a range of issues. The information below is a general overview of what to expect. If you have any questions about your recovery and how best to look after yourself when you get home, ask the doctors and nurses caring for you.

Pain relief – You will have some pain and discomfort for several days after surgery, but this can be controlled with pain medicines. Let the doctor or nurses know if the pain worsens – don’t wait until it is severe before asking for more pain relief.

Underwear – For the first couple of weeks, it’s best to wear underwear that provides cupping support for the scrotum. This will offer comfort and protection as you recover, and can also reduce swelling. You can buy scrotal support underwear at most pharmacies. It is similar to brief-style underwear and is not noticeable under clothing. You could also wear regular close‑fitting underwear with padding placed under the scrotum. Avoid wearing loose-fitting underwear such as boxer shorts.

Daily activities – You will need to take care while you recover. It will be some weeks before you can lift heavy things, exercise vigorously, drive or resume sexual activity. Ask your doctor how long you should wait before attempting any of these activities or returning to work.

Fertility – As long as the remaining testicle is healthy, losing one testicle is unlikely to affect your ability to have children. However, some people may have fertility problems if the remaining testicle is small and doesn’t make a lot of sperm. The urologist may advise you to store some sperm at a sperm-banking facility before the surgery, just in case you have fertility problems in the future or need to have chemotherapy after surgery.

Stitches and bruising – You will have a few stitches to close the incision. These will usually dissolve after several weeks. There may be some bruising around the wound and scrotum. The scrotum can become swollen if blood collects inside it (intrascrotal haematoma). If this occurs, the swelling may make it feel like the testicle hasn’t been removed. Both the bruising and the swelling will disappear over time.

Sex and body image – Your ability to get an erection and experience orgasm should not be affected by the removal of one testicle. However, some people find that it takes time to adjust to the changes to their body and this may affect how they feel about sex and intimacy. Some people choose to replace the removed testicle with an artificial one (prosthesis).

How you might feel – After your testicle is removed, you may feel sad, depressed, embarrassed or anxious. Usually these feelings will get better in time, but it may help to talk about how you are feeling with someone you trust, such as a partner, friend or counsellor.

Gentle exercise – Try to do some gentle exercise. This can help build up strength and lift mood. Start with a short walk and go a little further each day. Speak to your doctor about when you can return to your usual activities.

Having a prosthesis

You may decide to replace the removed testicle with a testicular prosthesis to improve how the scrotum looks. A prosthesis is a silicone implant similar in size and shape to the removed testicle. There are different brands, and some feel firmer than others. Whether or not to have a prosthesis is a personal decision. If you choose to have a prosthesis, it can be inserted into the scrotum at the same time as the orchidectomy or at a later time. Ask your urologist for more information about your options.

Further tests

If the pathology report on the removed testicle and other test results show that you have cancer, you will have further tests to see whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes or other organs. These tests may also be used during or after treatment to check how well the treatment has worked.

CT scan

You will have a CT (computerised tomography) scan of your chest, abdomen and pelvis. Sometimes this is done before the orchidectomy. A CT scan uses x-rays to take pictures of the inside of your body and then compiles them into one detailed, cross-sectional picture. To make the scan pictures clearer and easier to read, you may have to fast (not eat or drink) for a period of time before your appointment.

Before the scan, you may be given an injection of a dye into a vein in your arm to make the pictures clearer. This injection can make you feel hot all over for a few minutes. You might also feel like you need to urinate, but this sensation won’t last long. You may be asked to drink a liquid instead of having an injection.

The CT scanner is large and round like a doughnut. You will lie still on a table that moves slowly through the scanner while it takes pictures. The test is painless and takes about 15 minutes.

MRI scan

In some circumstances, such as if you have an allergy to the dye normally used for a CT scan, you may instead have an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan. An MRI uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed pictures of areas inside the body.

Before the scan, let your medical team know if you have a pacemaker or any other metallic object in your body, as the magnet can interfere with the metal. Newer pacemakers are often MRI-compatible.

You will lie on a table that slides into the scanner, which is a metal cylinder that is open at both ends. Sometimes, a dye (known as contrast) will be injected into a vein before the scan to help make the pictures clearer. The scanner makes a series of bangs and clicks and can be quite noisy.

The scan is painless, but some people feel anxious lying in the narrow cylinder. Tell your doctor or nurse beforehand if you are prone to anxiety or claustrophobia. They can suggest breathing exercises or give you medicine to help you relax. The scan takes about 30 minutes, and most people are able to go home as soon as it is over.

PET–CT scan

In some limited circumstances, you may also be given a PET (positron emission tomography) scan combined with a CT scan. You will be injected with a small amount of a glucose (sugar) solution containing some radioactive material, then asked to rest for 30–60 minutes while the solution spreads throughout your body before you have the scan. Cancer cells show up more brightly on the scan because they absorb more of the glucose solution than normal cells do.

It may take a few hours to prepare for a PET–CT scan, but the scan itself usually takes about 15 minutes. The radioactive material in the glucose solution is not harmful and will leave your body within a few hours.

All tests and scans have risks and benefits, and you should discuss these with your doctor. Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dye (contrast) during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease.

Staging and prognosis of testicular cancer

The tests completed by your specialist will help to show whether the testicular cancer has spread elsewhere in your body (the stage). There are several staging systems for testicular cancer, but the most commonly used is the TNM system.

Based on the TNM scores and the levels of tumour markers in the blood, the doctor then works out the cancer’s overall stage from stage 1 to stage 3. Most testicular cancers are found at stage 1. Each of the following stages is further divided into several sub-stages, such as A, B and C:

- stage 1 – cancer is found only in the testicle (early-stage cancer)

- stage 2 – cancer has spread outside the testicle to nearby lymph nodes in the abdomen or pelvis

- stage 3 – cancer has spread to lymph nodes outside the abdomen or pelvis (e.g. in the chest) or other areas of the body.

TNM staging system

In this system, letters and numbers are used to describe the cancer, with higher numbers indicating larger size or spread.

T (tumour) - describes whether the cancer is only in the testicle (T1) or has spread into nearby blood vessels or tissue (T2, T3, T4)

N (nodes) - describes whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes in the abdomen – N0 means it has not and N1–3 means it has

M (metastasis) - describes whether the cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes, organs or bones – M0 means it has not and M1 means it has

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease. To assess your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- your test results

- the type of testicular cancer you have

- the stage of the cancer

- other factors such as your age, fitness and medical history.

Testicular cancer has the highest survival rates of any cancer (other than common skin cancers). Regular monitoring and review (active surveillance) are major factors in ensuring good outcomes, so it’s vital that you attend all your follow-up appointments.

Treatment for testicular cancer

The treatment recommended by your doctors will depend on:

- your general health

- the type of testicular cancer you have (seminoma or non-seminoma)

- the size of the tumour

- the tumour marker levels on your blood test

- the number and size of any lymph nodes involved

- whether the cancer has spread to other parts of your body.

Most people have an orchidectomy to remove the affected testicle. If the cancer hasn’t spread, this may be the only treatment needed. After the surgery, you will need to have regular check-ups and tests to ensure that the cancer hasn’t come back. This is called active surveillance.

If the cancer has spread, after an orchidectomy you may have:

- chemotherapy to kill any remaining cancer cells and prevent the cancer from coming back

- radiation therapy to treat the lymph nodes in the abdomen

- more surgery to remove lymph nodes in the abdomen (retroperitoneal lymph node dissection or RPLND).

Chemotherapy, radiation therapy and RPLND can affect your fertility. This may be temporary or permanent. If you may want to have children in the future, ask your doctor for a referral to a fertility specialist before treatment starts. You may be able to store sperm for later use.

Active surveillance

If you had an orchidectomy and the cancer was completely removed, you may not need any further treatment. Instead, you will have active surveillance, with regular physical examinations, blood tests (for tumour markers) and imaging (CT scans and/or chest x-rays) for 5–10 years.

Active surveillance can help find if there is any cancer remaining (residual cancer). It can also help work out if the cancer has come back (recurrence). How often you will need check-ups and tests will depend on whether you had seminoma or non-seminoma testicular cancer. Your doctor will talk to you about a suitable schedule for you.

It’s important to follow the surveillance schedule outlined by your doctor. It may be tempting to skip appointments if you are feeling better, you were diagnosed with early-stage cancer, or you are busy. However, if cancer does come back, active surveillance can help to find it early when it is easier to treat.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells while doing the least possible damage to healthy cells. Chemotherapy may be used at different stages of testicular cancer.

To reduce the risk of recurrence – If you have early testicular cancer that has not spread (stage 1), instead of active surveillance you may be offered chemotherapy after surgery. This is called adjuvant chemotherapy. Your doctor will discuss whether active surveillance or adjuvant chemotherapy is appropriate for you. Adjuvant chemotherapy usually consists of 1–2 cycles. You will then be monitored with check‑ups and tests for 5–10 years (active surveillance).

To treat cancer that has spread – If you have stage 2 or 3 testicular cancer, chemotherapy may be recommended after surgery to destroy any cancer cells that have spread. This usually involves 3–4 cycles of chemotherapy. Your doctor will discuss the treatment plan with you. Depending on how you respond to the treatment, you may need more surgery or chemotherapy. You will then have active surveillance for 5–10 years.

Before surgery (neoadjuvant) – Rarely, when the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, chemotherapy may be given before surgery (orchidectomy) to help control the spread and reduce symptoms.

Treatment after chemotherapy – You may need further surgery to remove any tumours that haven’t completely disappeared after chemotherapy. These lumps are called residual masses and they are most commonly found in the lymph nodes in the abdomen. Surgery to remove these lymph nodes is called a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND).

Having chemotherapy

There are many types of chemotherapy drugs. Some people are given a drug called carboplatin, which is often used for early-stage seminoma cancer after surgery. Other drugs commonly used for both seminoma and non-seminoma testicular cancer are bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin. These 3 drugs used together are called BEP chemotherapy.

Generally, chemotherapy is given through a drip inserted into a vein (intravenously). Bleomycin may also be given by injection into a muscle (intramuscularly). Chemotherapy is commonly given as a period of treatment followed by a break. This is called a cycle. The length of the cycle depends on the drugs used.

The number of chemotherapy cycles you have will depend on the type and stage of the cancer. Your medical oncologist will explain your treatment schedule. Usually, you have chemotherapy during day visits to a hospital or treatment centre. For some types of chemotherapy, you may need to attend hospital several days in a row.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Everyone reacts differently to chemotherapy. Some people don’t experience any side effects, while others have a few. Side effects are usually temporary, and there are medicines that can help reduce your discomfort. Talk to your doctor or nurse about any side effects you have and ways to manage them.

It’s common to feel tired, have nausea or vomiting, lose some hair from your body and head, have erection problems, bowel issues, tingling in the hands and feet, and ringing in the ears. Chemotherapy can also affect your fertility and, in the long term, increase the risk of heart disease and developing a second cancer.

About a week after a treatment session, your white blood cell levels may drop, making you more likely to get infections. If you feel unwell or have a temperature of 38°C or higher, call your treatment team or go to a nearby hospital emergency department. Before chemotherapy, you may have injections to boost your immunity and protect you from infection.

Using contraception during treatment

Even when treatment lowers the amount of sperm you make, there is still a chance a sexual partner could become pregnant. Because chemotherapy can damage sperm, you will need to use barrier contraception (such as condoms or female condoms) during treatment to prevent pregnancy. Sometimes this may need to continue for some months after treatment finishes. Your doctor will discuss this with you in more detail.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. The radiation is usually in the form of focused, high-energy x-ray beams.

Radiation therapy is not used very often for testicular cancer. It may be used instead of chemotherapy or surgery to treat seminoma cancer that has spread to lymph nodes in the abdomen.

Having radiation therapy

Treatment is carefully planned to ensure that any remaining cancer cells are destroyed while causing the least possible harm to normal tissue. During a radiation therapy session, you will lie under a machine called a linear accelerator. The radiation is directed at the cancerous lymph nodes. The unaffected testicle may be covered with a lead barrier to help preserve your fertility.

Radiation therapy is painless and can’t be seen or felt. It is just like having an x-ray taken. The treatment itself takes only a few minutes, but each session may last 10–15 minutes because of the time it takes to set up the equipment and place you in the correct position. Most people have daily treatment sessions at a radiation therapy centre from Monday to Friday for 2–4 weeks. Your doctor will let you know how many sessions you need.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy can injure healthy cells at or near the treatment areas. This can cause a range of side effects, including fatigue, stomach and bowel problems, hair loss in the treatment area and bladder irritation. In most cases, radiation therapy for testicular cancer won’t irritate the skin in the treatment area. If the skin does become red or sore, ask your treatment team about what type of cream to use to moisturise the skin.

Side effects often build up slowly and may be worse at the end of radiation therapy. Most side effects are temporary and go away in time, usually within a few weeks of treatment finishing. In the longer term, radiation therapy can affect your fertility, and increase the risk of developing a second cancer.

Your radiation oncologist will see you at least once a week to monitor and treat any side effects during the course of your treatment. You can also talk to a nurse if you are concerned about side effects.

Surgery to remove lymph nodes

If testicular cancer does spread, it most commonly spreads to the lymph nodes at the back of the abdomen (the retroperitoneum). In some cases, an operation called a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND or lymphadenectomy) is done to remove these lymph nodes.

Non-seminoma cancer – If scans show that lymph nodes have not returned to normal size after chemotherapy, they may still contain cancer cells and your doctors may recommend you have an RPLND. Some people have an RPLND instead of chemotherapy to treat enlarged lymph nodes found after an orchidectomy. This may happen because the type of non-seminoma cancer is not likely to respond to chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or to avoid some of the side effects of chemotherapy.

Seminoma cancer – Chemotherapy or radiation therapy usually destroys seminoma cancer cells in the lymph nodes, so an RPLND is not often needed. If enlarged lymph nodes do remain after these treatments, you may be offered an RPLND. A small number of people may have an RPLND instead of chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Having an RPLND

An RPLND is a long, complex operation that should be performed by an experienced surgeon in a specialist centre that does a high number of these procedures. There are 2 ways to perform an RPLND and your surgeon will discuss which approach is suitable for you.

The standard approach involves open surgery, with a large cut made from the breastbone to below the bellybutton. The surgeon moves the organs out of the way, then removes the lymph nodes and any remaining cancer (residual masses) from the back of the abdomen.

In select cases, some highly trained surgeons may offer robotic (keyhole) surgery. The surgeon inserts surgical instruments through several small cuts in the abdomen with help from a robotic system.

Side effects of RPLND

It can take many weeks to recover from an RPLND. At first, you will probably be very tired and may not be able to do as much as you’re used to. Take it easy and pace yourself. Other side effects include:

Pain – It is common to have pain and tenderness in the abdomen. Your doctor can prescribe pain medicines to make you more comfortable.

Ejaculation – An RPLND may damage the nerves controlling ejaculation. This can cause retrograde ejaculation, which is when semen travels backwards into the bladder, rather than forwards out of the penis. Your surgeon may be able to use a technique called nerve-sparing surgery that avoids damaging these nerves, but this is not always possible. Although retrograde ejaculation is not harmful, it usually causes infertility. If having children is important to you, talk to your surgeon about storing some sperm before an RPLND.

Palliative treatment

Rarely, testicular cancer is so advanced that treatment cannot make it go away and your doctor may talk to you about palliative treatment. This is treatment that helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease.

Many people think that palliative treatment is for people at the end of their life, but it may help at any stage of advanced cancer. It is about living for as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can. As well as slowing the spread of the cancer, palliative treatment can relieve pain and help manage other symptoms. Treatment options may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy or other medicines.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, practical, emotional, spiritual and social needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Managing side effects

It will take time to recover from the physical and emotional changes caused by treatment for testicular cancer.

Side effects may last from a few weeks to a few months or, in some cases, years or permanently.

Ways to look after your health after treatment

Many people live a long time after treatment for testicular cancer. Finding ways to look after yourself can improve your quality of life and reduce the risk of developing more serious long-term side effects.

Regular exercise can help improve mood, heart health, energy levels and muscle strength. Whatever your age or fitness level, a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist can develop an exercise program to meet your needs. Ask your doctor for a referral.

To reduce the risk of weight gain and high cholesterol, aim to eat a balanced diet with a variety of fruit, vegetables, wholegrains and protein-rich foods. It may help to see a dietitian for advice.

If you have ongoing side effects after cancer treatment, talk to your GP about developing a chronic disease management plan to help you manage the condition. This means you may be eligible for a Medicare rebate for up to 5 visits each calendar year to allied health professionals.

Common short term side effects

Fatigue

It is common to feel tired and lack energy while having chemotherapy or radiation therapy, particularly as treatment progresses. The tiredness often lasts for a few weeks after treatment is finished. Try doing some gentle exercise as this can help with fatigue. Plan your activities so you can rest regularly during the day. Talk to your family and friends about how they can help you.

Stomach problems

Some chemotherapy drugs can make you feel ill (nausea) or vomit. You will usually be given anti-nausea medicine before having chemotherapy to prevent or reduce nausea and vomiting. You may be given other anti-nausea medicines to take at home in case nausea occurs. These are available in many forms, including tablets that you swallow, wafers that dissolve on the tongue and suppositories to put in your bottom (rectum).

If you have radiation therapy to the abdomen, you could have some minor stomach-aches, nausea or bloating. Your doctor may prescribe medicines to prevent these symptoms from occurring or to treat them if they do occur. Make sure to tell your medical team if you still feel sick as you may be able to try a different form of medicine.

Bowel issues

Sometimes chemotherapy drugs can affect the nerve endings in the bowel, making it hard to pass a bowel motion and causing constipation. More often, constipation occurs as a side effect of the anti-nausea medicines. Your medical team can prescribe medicines to help treat constipation.

Radiation therapy sometimes causes diarrhoea and cramping. These bowel irritations are usually minor and do not need treatment, but if they are bothering you, talk to your doctor about adjusting what you eat or taking medicines.

Bladder irritation

Radiation therapy may cause the bladder and urinary tract to become irritated and inflamed. Drinking plenty of fluids will help, but avoid alcoholic or caffeinated drinks, as they can irritate the bladder further.

Hair loss

Chemotherapy often causes hair loss from the head and body. Radiation therapy may cause you to lose pubic and abdominal hair in the treatment area. After treatment, the hair will usually grow back.

Peripheral neuropathy

Some chemotherapy drugs affect the nerves, causing numb, painful or tingling fingers or toes. This is called peripheral neuropathy. It can start during treatment or after chemotherapy is finished. It usually improves over 6–12 months, but is sometimes long-lasting.

Hearing problems

Some chemotherapy drugs can cause short-term ringing or buzzing in the ears (tinnitus) and affect the ability to hear high-pitched sounds.

Breathlessness, cough or other symptoms

Some drugs can damage the lungs or kidneys. You may have lung and kidney function tests to check the effects of the drugs on your organs.

Long-term side effects

Treatment for testicular cancer can sometimes lead to long-term side effects. Your doctors will discuss these with you before treatment starts.

Effects on the heart and blood vessels

Having chemotherapy for testicular cancer can affect the heart and blood vessels. This can increase the longer-term risk of developing heart disease, stroke or blood circulation problems. Having high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, high blood sugar levels or carrying excess weight can increase this risk. Many people can manage their cholesterol and blood pressure levels with regular exercise and a balanced diet. Other people may be prescribed medicines. Talk to your doctor about whether you need regular heart checks after treatment and ways you can look after your heart and blood circulation. If you develop heart or circulation problems, make sure to let your doctors know you had treatment for testicular cancer.

Risk of other cancers

People who have chemotherapy for testicular cancer are at a slightly higher risk of developing leukaemia, which is a blood cancer. Having chemotherapy may also increase the risk of developing a new unrelated solid cancer. People who have radiation therapy for testicular cancer have a slightly increased risk of developing a second cancer in or near the area exposed to radiation. The risk of developing a second cancer is very low. Talk to your doctors about things you can do to reduce this risk, such as following your surveillance schedule, and exercising, being a health body weight and eating well.

Low testosterone levels

Some people will develop low testosterone levels after treatment for testicular cancer (known as hypogonadism). Having chemotherapy after surgery can increase the risk. Low testosterone levels may cause a range of issues, including tiredness, muscle loss and reduced sex drive. Testosterone levels will be checked as part of follow-up care and some people may need testosterone replacement therapy.

Changes to sex and intimacy

Surgery – Removing one testicle won’t affect erections or orgasms but can affect testosterone levels. RPLND may damage nerves, causing semen to travel backwards into the bladder instead of forwards out of the penis. This still feels like an orgasm, but no semen will come out.

Chemotherapy – Chemotherapy drugs may remain in your system and be present in your semen for a few days. Your ability to get and keep an erection may be affected for a few weeks after chemotherapy. This is usually temporary. You may also find you have a lower sex drive (libido).

Radiation therapy – Radiation therapy to the abdomen may temporarily stop you making semen. You will still feel the sensations of an orgasm but will ejaculate little or no semen (dry orgasm). In most cases, semen production returns to normal after a few months.

Managing changes to sex and intimacy

- Be gentle the first few times you are sexually active after treatment. Start with touching, and tell the person you’re having sex with, what feels good.

- Talk openly with your doctor or sexual health counsellor about any challenges. They may be able to help and reassure you.

- Protect your sexual partners from any drugs in your semen by using barrier contraception, such as condoms, during chemotherapy and radiation therapy and for a number of days afterwards, as advised by your doctor.

- Accept that tiredness and worry may lower your interest in sex, and remember that sex drive usually returns when treatment ends.

Effects on fertility

Surgery – Most men who have had one testicle removed can go on to have children naturally. Men who have both testicles removed (rarely required) will no longer produce sperm and will be infertile. Men who have retrograde ejaculation after RPLND cannot conceive naturally. You may be given medicine to help the semen move out of the penis as normal or a doctor may be able to extract some sperm.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy – Both chemotherapy and radiation therapy can decrease sperm production and cause unhealthy sperm. These effects may be temporary or permanent. It may take one or more years before there are enough healthy sperm to conceive a child.

Managing fertility changes

- Before cancer treatment starts, you may be able to collect and store some sperm. The sperm is frozen until needed. Samples can be stored for many years. Although there is a cost involved, most sperm bank facilities have payment plans to make it more affordable. Ask your cancer specialist to refer you to a fertility specialist so you can find out about your options.

- Avoid pregnancy until sperm are healthy again by using contraception during and after chemotherapy or radiation therapy for about 6–12 months, or as advised by your doctor. You may need a sperm analysis test to show this.

- If infertility appears to be permanent, talk to a counsellor or family member about how you are feeling. Infertility can be very upsetting for you and your family, and you may have many mixed emotions about the future.

Effects on body image

Surgery – If you have had a testicle removed, it may affect how you feel about yourself as a man. You may have less confidence and feel less sexually desirable. Some men adjust quickly to having one testicle, while others find that it takes some time. If you had an RPLND, you may feel self-conscious about the scar across your abdomen.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy – Any type of cancer treatment can change the way you feel about yourself (your self-esteem). You may feel less confident about who you are and what you can do, particularly if your body has changed physically. Some men find that their sense of identity or masculinity is affected by their cancer experience.

Adjusting to changes to your body

- Give yourself time to get used to any changes to your body. Try to see yourself as a whole person (body, mind and personality) instead of focusing on the parts of you that have changed.

- Talk to other people who have had a similar experience. You can call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to find out about our peer support programs or visit the Cancer Council Online Community.

- Let your partner, if you have one, know how you are feeling. Show your partner any changes and let them touch your body, if you are both comfortable with this.

- If you continue to be concerned about your appearance, you may wish to speak to your medical team about getting an artificial testicle (prosthesis).

- You may also find it helpful to talk to a psychologist if you are having trouble adjusting to any changes – ask your GP for a referral.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had testicular cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back. Active surveillance for testicular cancer usually continues for 5–10 years. How often you see your doctor will depend on the cancer type, treatments, and side effects you have. During the check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination and you may have blood tests (to monitor tumour markers), x-rays or scans.

Treatment for testicular cancer usually has a good outcome and the majority of people with early-stage cancer will be cured. Only about 2–5% of people who have had cancer in one testicle develop cancer in the other testicle. However, some people have a recurrence of cancer in another part of the body.

It’s important to go to all your follow-up appointments, as tests can detect cancer recurrence early, when it is easier to treat. Regularly looking at and feeling your remaining testicle to know what’s normal, can also help find cancer in that testicle early. Between follow-up appointments, it’s important to let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if testicular cancer returns?

Sometimes testicular cancer does come back (recur) after treatment. This is why active surveillance is important. There is still a good chance that a recurrence may be successfully treated. Treatment will depend on whether the cancer is in the other testicle, where it has spread to, and what type of testicular cancer it is. People with recurrent cancer may have surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy or a combination of treatments. Your doctor will discuss options with you.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA also runs a free counselling program.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on

1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.