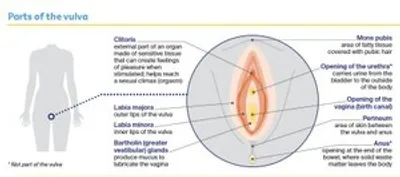

The vulva

The vulva is a general term for a female’s external sexual organs (genitals).

The main parts of the vulva are shown in the diagram below.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about vulvar cancer are below.

What is vulvar cancer?

Vulvar cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in any part of the vulva. It is also called vulval cancer or cancer of the vulva.

It most commonly develops in the skin of the labia majora, labia minora and the perineum. Less often, it involves the clitoris, mons pubis or Bartholin glands. As the cancer grows, it can spread to areas near the vulva, such as the vagina, bladder or anus.

Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, so that each new cell replaces one lost. Sometimes cells become abnormal and keep growing. These abnormal cells may form a lump called a tumour. If the cells in a tumour are cancerous, they can spread through the bloodstream or lymph vessels and form another tumour at a new site. This new tumour is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

How common is vulvar cancer?

Vulvar cancer is rare – about 420 women are diagnosed each year in Australia. It is more likely to affect women who have gone through menopause (stopped having periods), but it can occur at any age.

Anyone with a vulva can get vulvar cancer – women, transgender men, non-binary people and intersex people. For more information, speak to your doctor or see our ‘LGBTQI+ People and Cancer’ booklet.

What are the main types of vulvar cancer?

The types of vulvar cancer are named after the cells they start in.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- starts in thin, flat (squamous) skin cells covering the surface of the vulva

- most common type (about 9 out of 10 cases)

- verrucous carcinoma is a rare subtype that looks like a large wart and grows slowly

Vulvar (mucosal) melanoma

- starts in skin cells (melanocytes) found in the lining of the vulva

- less than 1 out of 10 cases

There are also rarer types of vulvar cancer. These include sarcomas, adenocarcinomas, Paget disease of the vulva, and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).

What are precancerous vulvar cell changes?

Sometimes the squamous cells in the vulva start to change. These changes may be precancerous. This means there is an area of abnormal tissue (a lesion) in the vulva that is not cancer, but may develop into cancer over time if left untreated.

These lesions are called vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). They can be classified as:

- low grade (LSIL), which may go away without treatment and is linked to human papillomavirus (HPV)

- high grade (HSIL), which may develop into vulvar cancer and is linked to HPV

- differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), which may develop into vulvar cancer and is not usually linked with HPV but is linked with the skin condition lichen sclerosus.

Most cases of vulvar SIL don’t develop into vulvar cancer. Your doctor will explain the treatment options suitable for you.

What are the risk factors?

Vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) – Having vulvar SIL increases the risk of developing vulvar cancer. This condition changes the vulvar skin, and may cause itching, burning or soreness.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) – Many cases of vulvar cancer are caused by infection with HPV, which is a very common virus in people who are sexually active. HPV often causes no symptoms. Only some types of HPV cause cancer, and most people with HPV don’t develop vulvar or any other type of cancer. It can be many years between infection with HPV and the first signs of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) or vulvar cancer.

Other risk factors – These include:

- the skin conditions vulvar lichen planus, vulvar lichen sclerosus or extramammary Paget disease

- having had an abnormal cervical screening test or cancer of the cervix or vagina

- smoking tobacco (which can make cancer more likely to develop in people with HPV)

- being aged over 70 (a little over half of all vulvar cancers are in women over 70)

- having a weakened immune system.

What are the symptoms?

Early vulvar cancer often has no obvious symptoms. It is commonly diagnosed after having vulvar symptoms for months or years. These may include:

- an ulcer that won’t heal

- a lump, sore, swelling or wart-like growth

- itching, burning and soreness or pain in the vulva

- thickened, raised skin patches (may be red, white or dark brown)

- a mole on the vulva that changes shape or colour

- blood, pus or other discharge coming from an area of skin or a sore spot in the vulva (not related to your menstrual period)

- hard or swollen lymph nodes in the groin area.

Many women don’t look at their vulva, so they don’t know what is normal for them. The vulva can be difficult to see without a mirror, and you may feel uncomfortable examining your genitals. If you feel any pain in your genital area or notice any of these symptoms, visit your general practitioner (GP) so they can examine the area you are concerned about. Don’t let embarrassment stop you getting checked.

How is vulvar cancer diagnosed?

You are likely to have some of the following tests:

Physical examination

Your doctor will look at the vulva and examine your groin and pelvic area. They may also insert an instrument with smooth, curved sides (speculum) into your vagina, so the doctor can check the vagina and cervix for cancer.

Cervical screening test

This test looks for cancer-causing types of HPV in a sample of cells taken from the cervix or vagina. During the physical examination, the doctor uses a small brush or swab to remove some cells from the surface of the cervix. This test replaced the Pap test in 2017.

Colposcopy

This uses a magnifying instrument called a colposcope to look at the vulva, vagina and cervix. The colposcope is placed near your vulva but does not enter your body.

Biopsy

During a colposcopy, your doctor will usually take a small tissue sample (biopsy) from the vulvar area and possibly the vaginal area. A biopsy may be done under local anaesthetic, which numbs the area, or general anaesthetic, which sends you to sleep. Your doctor will explain how much bleeding to expect afterwards and how to care for the wound. A biopsy is the best way to diagnose vulvar cancer. The tissue sample will be sent to a laboratory for testing.

Imaging scans

If vulvar cancer is found, you may have one or more imaging scans to check if it has spread. These may include a chest x-ray, CT or MRI scan of the pelvis, or PET–CT scan.

To find out more about these scans, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Staging vulvar cancer

Staging describes the size of the cancer and how far it has spread. Knowing the stage helps doctors recommend the best treatment for you.

Stage 1 - Cancer is found only in the vulva; no spread to lymph nodes.

Stage 2 - Cancer is found in the vulva and has also spread to the lower urethra, the lower vagina or the lower anus; no spread to lymph nodes.

Stage 3 - Cancer is found in the vulva and/or perineum and has also spread to one or more of the following areas: the upper urethra, upper vagina, the lining of the bladder or rectum, or lymph nodes in the groin.

Stage 4 - Cancer has spread to the bone or more distant parts of the body, or has spread to nearby lymph nodes causing them to become fixed (stuck to other tissue) or ulcerated (open sores).

Treatment for vulvar cancer

Because vulvar cancer is rare, it is recommended that you are treated in a specialist centre for gynaecological cancer.

If you have to travel for treatment, there may be a program in your state or territory to refund some of the cost of travel and accommodation. The hospital social worker can help you apply or you can call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

The multidisciplinary treatment (MDT) team may include a surgeon (usually a gynaecological oncologist), radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, specialist nurses, and allied health professionals, such as a physiotherapist or psychologist.

The treatment recommended by your doctor will depend on the results of your tests, the type of cancer, where the cancer is, whether it has spread, your age and your general health.

Understanding the disease, treatments, possible side effects and costs can help you weigh up the treatment options and make a well-informed decision. You may want to get a second opinion from another specialist to confirm the treatment options.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for vulvar cancer. A gynaecological oncologist will try to remove all of the cancer along with some of the surrounding healthy tissue (called a margin). This helps reduce the risk of the cancer coming back. Some lymph nodes in your groin may also be removed.

How much of the vulva is removed depends on the location of the tumour and how far the cancer has spread. Your gynaecological oncologist will talk to you about the risks and possible complications of surgery, as well as side effect).

Types of vulvar surgery

Wide local excision - Used for precancerous changes; the surgeon cuts out the precancer only.

Radical local excision - Used for small cancers; the surgeon cuts out the cancer and a margin of healthy tissue.

Partial radical vulvectomy - Used when the cancer is on one side of the vulva only; the surgeon removes a large part of the vulva and nearby lymph nodes.

Complete radical vulvectomy - Used when the cancer covers a large area of the vulva; the surgeon removes the whole vulva (including the clitoris), surrounding deep tissue and nearby lymph nodes.

Lymph node surgery - You may need to have lymph nodes in the groin removed to check for the spread of cancer. This may be through a:

- sentinel lymph node biopsy – used for some cancers less than 4 cm to find the lymph node that the cancer is most likely to spread to first (the sentinel node). If cancer is found in the sentinel lymph node, you will need a separate procedure called a lymphadenectomy

- lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection) – to remove some or all of the lymph nodes from one or both sides of the groin.

Reconstructive surgery - You may be able to have the skin around the wound drawn together with stitches. These will dissolve and disappear as the wound heals. If a large area of skin is removed, you may need a skin graft or skin flap. In this case, flaps of skin in the vulvar area are moved to cover the wound. Rarely, the surgeon may take a thin piece of skin from another part of your body (usually your abdomen or thigh) and stitch it over the wound.

Recovery after surgery

How long recovery takes will depend on the type of surgery you had and your general health. If only a small amount of skin is removed from the vulva, the wound is likely to heal quickly and you may go home in 1–2 days. If the surgeon removed a large amount of vulvar skin or some lymph nodes, recovery will take longer. You may spend up to a week in hospital.

Drains – If lymph nodes are removed, you may have a tube placed into the groin to drain fluid from the surgical site into a bag. This is called a surgical drain and it may be removed before you leave hospital. If you go home with the drain still in place, nurses will show you how to look after the drain and your doctor will tell you when it can be removed.

Pain – You will be given medicine to control any pain. Your doctor will tell you how soon you can stand up and walk after surgery, and how to avoid the stitches coming apart. It may be more comfortable to wear loose-fitting clothing without underwear.

Catheter – You may have a tube called a catheter to drain urine from your bladder into a bag. The catheter may be removed the day after surgery or stay in place for several days, depending on how close the surgery was to the opening of the bladder.

Taking care of yourself at home after surgery

Wound care - Before you leave hospital, the nurse will show you how to look after the wound at home. You will need to wash it with water 4 times a day using a handheld shower head or soft, squeezable plastic water bottle. You will also need to rinse the vulva after urinating or having a bowel movement. Dry the vulva well by patting dry with a clean towel or using a hairdryer on a low setting. If the area is numb, be careful when patting it dry. Infection is a risk after vulvar surgery, so report any redness, pain, swelling, wound discharge or unusual smell to your doctor or nurse.

Using the toilet - If the opening to your urethra is affected, you may find that going to the toilet is different. The urine stream might spray in different directions or go to one side. It may help to sit down towards the back of the toilet seat or adjust your position to control the flow of urine. You can also use a female urinary device, which is a soft funnel that helps direct the flow of urine. You can buy these at camping stores or online.

Rest - You will need to take things easy and get plenty of rest in the first week. Avoid sitting for long periods of time if it is uncomfortable, or try sitting on a pillow or 2 rolled towels to support the buttocks and reduce pressure on the wound.

Emotions - If part of your genital area is removed, you may feel a sense of loss and grief. You may also think differently about your body. It may help to share your feelings with someone you trust or seek professional support.

Exercise - Check with your treatment team about when you can start doing your regular activities. You may not be able to lift anything heavy, but gentle exercise such as walking can help speed up recovery. Because of the risk of infection, avoid swimming until your doctor says you can.

Driving - You will need to avoid driving after the surgery until your wound has healed and you are no longer in pain. Discuss this issue with your doctor. Check with your car insurer for any restrictions about driving after surgery.

Sex - Sexual activity needs to be avoided for about 6–8 weeks after surgery. Ask your doctor when you can restart sexual activity, and explore other ways you and your partner can be intimate.

Common treatment side effects

Possible side effects are fatigue; change in how the genitals look; scar tissue; difficulty urinating; lymphoedema (if lymph nodes removed); pain; sexual problems; trouble controlling the flow of urine (urinary incontinence); bowel changes.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy, also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is usually from x-ray beams.

Whether you have radiation therapy depends on the stage of the cancer, its size, and if it has spread to the lymph nodes. You may have radiation therapy:

- after surgery to help destroy any remaining cancer cells and reduce the risk of the cancer coming back

- before surgery to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove

- as the main treatment for advanced vulvar cancer, often combined with chemotherapy.

Radiation therapy for vulvar cancer is usually delivered from outside the body (external beam radiation therapy or EBRT). You will lie on a treatment table while a machine, called a linear accelerator, directs radiation towards the affected areas of the pelvis. You will have a planning session, including a CT or MRI scan, to work out where to direct the radiation beams. This may take up to 45 minutes. The actual treatment takes only a few minutes each time and is painless.

EBRT for vulvar cancer is usually given daily, Monday to Friday, over 5–6 weeks. Your radiation oncologist will discuss your treatment plan and side effects.

Common treatment side effects

Possible side effects are fatigue; skin reactions (dry, itchy and tender skin, peeling skin); sore and swollen vulva; changes to the vagina (dryness, shortening, narrowing); vaginal discharge; loss of pubic hair; bladder and bowel changes; urinary incontinence; lymphoedema; sexual problems; menopause (when periods stop).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells. You may have chemotherapy:

- during a course of radiation therapy, to make the radiation treatment more effective (known as chemoradiation or chemoradiotherapy)

- to control cancer that has spread outside the vulva.

The drugs are usually given by injection into a vein (intravenously). You will usually have several treatment sessions, with rest periods in between. Treatment is usually given during day visits to a hospital or clinic as an outpatient. Rarely, you may need to stay in hospital for a couple of nights.

Common treatment side effects

Possible side effects are fatigue; nausea; increased risk of infection.

Managing side effects of treatment for vulvar cancer

Treatment for vulvar cancer can sometimes lead to long-term, life-changing side effects.

Changes to the vulva and vagina

Surgery to the vulva can cause physical changes. If the labia have been removed, you will be able to see the opening to the vagina more clearly. If scar tissue has formed around the outside of the vagina, the entrance to the vagina will be narrower. If the clitoris has been removed, there will now be an area of flat skin without the usual folds of the vulva.

Radiation therapy may make your skin dry, itchy and tender in the treatment area. Talk with your treatment team about ways to manage these changes. Skin reactions will gradually improve after treatment finishes. Pelvic radiation therapy can also narrow the vagina, causing thinning of the vaginal walls and dryness.

You may be offered vaginal dilators to help keep the vagina open and prevent it from closing over. Using dilators may help make sex and follow-up pelvic examinations more comfortable. Ask your doctor, nurse or physiotherapist for more information about using vaginal dilators. They may also suggest using hormone creams or vaginal moisturisers to help with vaginal discomfort and dryness.

Sex

Sometimes surgery or radiation therapy can affect nerves and tissue in the pelvic area, causing scarring, narrowing of the vagina, swelling and soreness. This can make sex painful. If you’ve had your clitoris removed, you may have difficulty reaching orgasm. Take time to explore and touch your body to find out what feels good. Using extra lubrication may make sexual activity more comfortable. Choose a water-based or silicone-based gel without perfumes or colouring.

Sexual desire (libido)

Changes to the look and feel of your vulva can cause embarrassment, loss of sexual pleasure, and less interest in sex. The experience of having cancer can also reduce your desire for sex. You may wish to have counselling to help understand the impact treatment has had on your sexuality. A sex therapist or psychologist can help you (and your partner if you have one) adjust to changes and find new ways to express intimacy and enjoy sex. Ask your doctor for a referral.

Bladder changes

Incontinence is when urine leaks from your bladder without your control. Bladder control may change after surgery or radiation therapy to the vulva. Some people find they need to pass urine more often or feel that they need to go in a hurry. Others may leak a few drops of urine when they cough, sneeze, strain or lift. For ways to manage incontinence, talk to the hospital continence nurse or physiotherapist.

Lymphoedema

If the lymph nodes have been removed during surgery or scarred during radiation therapy, lymph fluid can build up in the tissues under the skin. This is called lymphoedema, and it can cause swelling in the legs, vulva or mons pubis. Lymphoedema may appear during treatment or months or years late. Not everyone who is at risk will develop swelling. It is important to seek help, because early diagnosis and treatment can lead to better outcomes. A lymphoedema practitioner can develop a treatment plan for you.

Coping with your emotions

It is common to feel shocked and upset about having cancer in one of the most intimate and private areas of your body.

You may feel a wide variety of emotions after the diagnosis and during treatment, including anger, fear, anxiety, sadness and resentment.

Having parts of your vulva, including the clitoris, removed can affect your self-image. If you decide to look at your vulva, it is natural to be shocked by any changes. You may find that your sense of femininity or identity has been affected. Try to see yourself as a whole person (body, mind and personality), instead of focusing on the changes. It is important to give yourself and those around you time to deal with the emotions that a diagnosis of vulvar cancer can cause. For support, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment, you will have check-ups every 3–12 months for several years to monitor your health, manage any ongoing side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread.

Your doctor will talk to you about your follow-up schedule, which will depend on the risk of the cancer coming back. Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Let your doctor know immediately of any health concerns between appointments.

If the cancer comes back

For some people, vulvar cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. Depending on where the cancer recurs, treatment may include surgery, chemoradiation, radiation therapy or chemotherapy. You may also consider joining a clinical trial to try new treatments. For more information, talk to your doctor about suitable trials or visit Australian Cancer Trials. In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment.