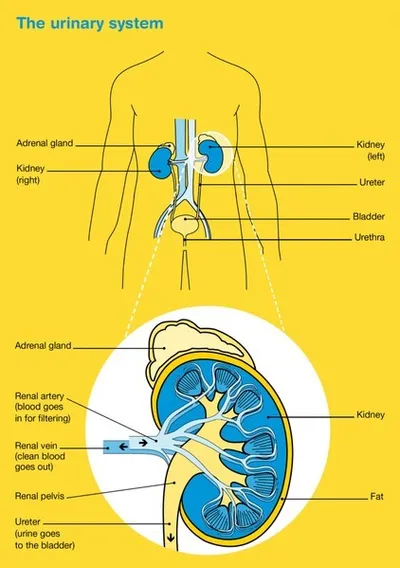

The urinary tract system

The normal urinary tract consists of two kidneys, two ureters, the bladder and the urethra. The upper tract consists of the renal calyces, renal pelvis and the ureters, while the lower tract consists of the bladder and urethra.

The urinary tract’s main purpose is to remove waste and extra fluid from the body in the form of urine (wee or pee), regulate blood pressure, maintain the body’s water balance and control the levels of chemicals and salts in the blood.

Your kidneys work hard. All your body’s blood passes through them every five minutes. The kidneys remove waste and excess fluid from the blood in the form of urine, which is then carried by the ureters to the bladder where it is stored.

To urinate normally, all the parts of your urinary tract system must work together. Your brain controls your bladder and sends signals when it is time to go to the toilet. Urine then empties from your bladder through your urethra and out of your body.

What is upper tract urothelial cancer?

Upper tract urothelial cancer (sometimes called transitional cell carcinoma) is a cancer that occurs in either the inner lining of the tube that connects the kidney to the bladder (the ureter) or within the inner lining of the kidney.

The renal pelvis is the upper end of the ureter that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. The kidney has several cup-like cavities, called calyces, where urine is collected. The calyces drain urine into the renal pelvis which acts as a funnel to the bladder. UTUC can occur in all of these areas.

The lining of the bladder, kidney and ureter are the same, so there are some similarities between upper tract urothelial cancer and bladder cancer. Blood in the urine (haematuria) is a symptom of both cancers, however, UTUC can block the ureter or kidney, causing swellings and infections and can affect kidney function in some people.

How common is upper tract urothelial cancer?

Around 470 Australians are diagnosed each year with UTUC. It is three times more likely to be diagnosed in men than women, and people aged over 70 years.

What are the symptoms and the risk factors?

Upper tract urothelial cancer can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages and you may have no symptoms if the cancer is slow growing.

Symptoms that some people may experience include:

- blood in the urine (haematuria) — you may or may not be able to see this

- pain on one side of the back caused by a blockage in the kidney or ureter

- weight loss

- urinary tract infections.

What are the risk factors?

The cause of UTUC is not known in most cases. However, there are several risk factors:

- smoking

- a history of long-term inflammation of the ureter or kidney

- exposure to certain chemicals over time, such as those used to make plastics, textiles, rubber, paint and dyes

- exposure to arsenic

- prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy for another cancer

- long-term use of large quantities of painkillers

- history of bladder cancer

- having Lynch syndrome (an inherited syndrome) or Balkan nephropathy (caused by exposure to toxins in the diet of people living in the Balkan region).

How is upper tract urothelial cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor thinks you may have UTUC they will take your medical history, perform a physical examination and arrange for you to have a number of tests.

If the results of these tests suggest that you may have UTUC, your doctor will refer you to a specialist called a urologist, who will arrange further tests. These may include:

Urine tests

You will be asked to collect a urine sample either at home or at your doctor’s surgery which will be checked for blood and bacteria. This may be a dipstick test (urinalysis) or it may involve sending your urine to a pathology laboratory to be checked. You may also need to collect urine samples over three days to be checked for cancer cells. This test is called urine cytology.

Blood tests

Blood tests will measure your white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets, and to check your kidney and liver function.

Ultrasound scan

This scan uses soundwaves to create pictures of the inside of your body. You will lie down on an examination table and a gel will be spread over the affected part of your body. A small device called a transducer is moved over the area. The transducer sends out soundwaves that echo when they come across something dense, like an organ or tumour. The images are then projected onto a computer screen. An ultrasound is painless and takes about 15–20 minutes.

CT (computerised tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) scans

These tests use special machines to scan and create pictures of the inside of your body. Before one of these scans, you may have an injection of dye (called contrast) into one of your veins, which makes the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table.

For a CT scan the table moves in and out of the scanner which is large and round like a doughnut; the scan itself takes about 10 minutes.

For an MRI scan the table slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends; this scan takes about 30–90 minutes. A PET scan involves having an injection of a small amount of radioactive material and then having a special CT scan. All of these scans are painless.

Cystoscopy and ureteroscopy

A cystoscopy involves looking in the bladder while a ureteroscopy involves looking up into the ureter to the kidney. A cystoscopy can usually be performed under a local anaesthetic. It uses a thin, flexible tube with a light and small camera on the end that is inserted into the urethra. This is at the tip of the penis or just above the vagina. A ureteroscopy test is usually performed under a general anaesthetic. First, a cystoscopy is performed then an even thinner tube (ureteroscope) is passed into the bladder then moved into the ureter and renal pelvis. Tissue samples may be removed (biopsy) for further examination under a microscope. For a few days after either test you may see some blood in your urine and feel mild discomfort when urinating.

Finding a specialist

Rare Cancers Australia have a directory of health professionals and cancer services across Australia.

Visit Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ) which is the peak membership organisation for urological surgeons and other health professionals working in the field of urology.

Grading and staging of upper tract urothelial cancer

If cancer cells are found during any of your tests, your doctor will need to know the grade and stage of the tumour so your team of health professionals can develop the best treatment plan for you.

The grade lets your doctor know how quickly the cancer might grow and spread while the stage describes its size and whether it has spread beyond the original site.

Grading

Upper tract urothelial cancers are graded as follows:

- Papillary urothelial neoplasia of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) – very slow growing and rarely recur or spread.

- low grade – the cancer cells are usually slow-growing and are less likely to invade and spread.

- high grade – the cancer cells look highly abnormal, they grow quickly and are more likely to spread.

The grade will tell your doctor how likely the cancer will be to recur and therefore determine the treatment you required. Most UTUC will need follow-up cystoscopies and/or ureteroscopies, imaging and urine tests annually.

Staging

The most common staging system for UTUC is the TNM system. In this system, letters and numbers are used to describe the cancer, with higher numbers indicating larger size or spread.

T stands for tumour - Ta, Tis and T1 are non-muscle-invasive cancer, while T2, T3 and T4 are muscle-invasive cancer.

N stands for nodes - N0 means the cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes, while N1, N2 and N3 indicate that it has spread to lymph nodes.

M stands for metastasis - M0 means the cancer has not spread to distant parts of the body, while M1 means it has spread to distant parts of the body.

Treatment for upper tract urothelial cancer

You will be cared for by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) of health professionals during your treatment for UTUC.

The team may include your GP, a urologist (to perform any surgery), medical oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate drug treatments which may include chemotherapy), radiation oncologist (to prescribe and deliver radiation therapy), pathologist (to examine cells and tissue samples to determine the type and extent of the cancer), specialist nurse and allied health professionals such as a dietitian, social worker, psychologist or counsellor, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Discussions with your health professionals will help you decide on the best treatment for your cancer depending on:

- the type of cancer you have and its exact location

- the grade and stage of your cancer

- your age, fitness and general health

- the health and function of your other kidney (if it is the kidney that is affected)

- your preferences.

The main treatments for UTUC include surgery, chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy. These can be given alone or in combination. This is called multi-modality treatment.

Surgery

Surgery is the most effective treatment for UTUC. Surgery may be performed as either keyhole surgery or open surgery. Each method has advantages in particular situations. Your doctor will talk to you about which type of surgery is appropriate for you.

- Keyhole (laparoscopic) surgery – the surgeon makes several small cuts (incisions) under general anaesthetic and passes a small tube with a camera (laparoscope) through one of the cuts. The camera sends images to a monitor. The surgeon then passes surgical tools through the other cuts to perform the procedure. A robot is sometimes used to help with keyhole surgery. Recovery from keyhole surgery is usually quicker that from open surgery.

- Open surgery – the surgeon makes a larger cut (incision) to perform the procedure.

The extent of the surgery depends on the location and stage of the tumour. Your surgeon will discuss the type of operation you may need.

Surgical procedures

Removing the whole kidney and ureter (nephroureterectomy) – The kidney, a layer of fat around the kidney and ureter are removed down to the bladder. An area of tissue where the ureter enters the bladder (bladder cuff) is also removed. The surgeon may also remove some regional lymph nodes to check if they contain cancer cells.

Removing part of the ureter (distal resection) – The bottom part of the ureter is removed down to the bladder. This is only possible if the tumour is in the pelvic part of the ureter. This procedure saves the kidney and the ureter is re-joined to the bladder.

Ureteroscopy – The surgeon passes a small tube with a camera (ureteroscope) into the bladder, ureter and renal pelvis. Often tissue samples are removed (biopsy) for further examination under a microscope.

Ureteroscopy surgery – Used for low-grade and early-stage cancers only. The surgeon passes a small tube with a camera (ureteroscope) through the urethra, bladder and ureter to the renal pelvis. The tumour is removed using laser or heat (diathermy).

Percutaneous renoscopy surgery – Used for low-grade and early-stage cancers only. The surgeon makes a small incision in your mid back and passes a small tube with a camera (endoscope) into your kidney to the renal pelvis. The tumour is removed using tools passed through the endoscope.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (sometimes just called “chemo”) is the use of drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. You may have one chemotherapy drug, or a combination of drugs. This is because different drugs work in different ways.

Your treatment will depend on your situation and stage of the tumour. Chemotherapy may be used before or after you have surgery. Sometimes after surgery to remove the kidney and ureter (nephroureterectomy) a single dose of chemotherapy “wash” is put into the bladder. Usually this will be a drug called mitomycin and is given via the catheter that is left for one to two weeks after the surgery. Doing this can reduce the chance of the cancer recurring in the bladder. Your medical oncologist will discuss your options with you.

Chemotherapy is usually given through a drip into a vein (intravenously) or as a tablet that is swallowed. Chemotherapy is commonly given in cycles which may be daily, weekly or monthly. For example, one cycle may last three weeks where you have the drug over a few hours, followed by a rest period before starting another cycle. The length of the cycle and number of cycles depends on the drugs being given.

Immunotherapy

If your cancer has spread and is now known as advanced or metastatic upper urothelial cancer you may be offered immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. A new group of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors are available that work by helping the immune system to recognise and attack the cancer.

A checkpoint immunotherapy drug called pembrolizumab is now available in Australia for some people with advanced upper tract urothelial cancer. The drug is given directly into a vein through a drip, and the treatment may be repeated every 2–4 weeks for up to two years. Other types of checkpoint immunotherapy drugs may become available soon. Clinical trials are testing whether combining newer checkpoint immunotherapy drugs with chemotherapy and radiation therapy will benefit people with upper urothelial cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses high energy x-rays to destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy, however, is less commonly used for UTUC. Your doctor will discuss your options with you.

A course of radiation therapy needs careful planning. During your first consultation session you will meet with a radiation oncologist who will arrange a planning session. At the planning session (known as CT planning or simulation) you will need to lie still on an examination table and have a CT scan in the same position you will be placed in for treatment. The information from the planning session will be used by your specialist to work out the treatment area and how to deliver the right dose of radiation. Radiation therapists will then deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan.

Radiation therapy does not hurt and is usually given in small doses over a period of time to minimise side effects.

Clinical trials

Your health professionals may suggest you take part in a clinical trial, or you can ask them if there are any clinical trials available for you. Cancer clinical trials are an important way to discover new treatments and methods to detect and diagnose cancer. If you join a randomised trial for a new treatment, you will be chosen at random to receive either the best existing treatment or the modified new treatment which has already been tested for safety. Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

You may find it helpful to talk to your specialist, clinical trials nurse or GP, or to get a second opinion. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time. For more information about types of clinical trials and how to join a study, visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Download our booklet 'Understanding Clinical Trials and Research'

Complementary therapies and integrative oncology

Complementary therapies are designed to be used alongside conventional medical treatments (such as surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy) and can increase your sense of control, decrease stress and anxiety, and improve your mood. Some Australian cancer centres have developed “integrative oncology” services where evidence-based complementary therapies are combined with conventional treatments to improve both wellbeing and clinical outcomes.

Some complementary therapies and their clinically proven benefits are listed below:

- acupuncture – reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; improves quality of life.

- aromatherapy – improves sleep and quality of life

- art therapy, music therapy – reduce anxiety and stress; manage fatigue; aid expression of feelings

- counselling, support groups – help reduce distress, anxiety and depression; improve quality of life

- hypnotherapy – reduces pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting

- massage – improves quality of life; reduces anxiety, depression, pain and nausea

- meditation, relaxation, mindfulness – reduce stress and anxiety; improve coping and quality of life

- qi gong – reduces anxiety and fatigue; improves quality of life

- spiritual practices – help reduce stress; instil peace; improve ability to manage challenges

- tai chi – reduces anxiety and stress; improves strength, flexibility and quality of life

- yoga – reduces anxiety and stress; improves general wellbeing and quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Download our booklet 'Understanding Complementary Therapies'

Nutrition and exercise

If you have been diagnosed with UTUC both the cancer and treatment will place extra demands on your body. Research suggests that eating well and exercising can benefit people during and after cancer treatment.

Eating a nutritious and well-balanced diet and being physically active can help you cope with some of the common side effects of cancer treatment, speed up recovery and improve quality of life by giving you more energy, keeping your muscles strong, helping you maintain a healthy weight and boosting your mood.

You can discuss individual nutrition and exercise plans with health professionals such as dietitians, exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Download our booklet 'Nutrition for People Living with Cancer'

Download our booklet 'Exercise for People Living with Cancer'

Side effects of treatment

All treatments can have side effects. The type of side effects that you may have will depend on the type of treatment and where in your body the cancer is. Some people have very few side effects and others have more. Your specialist team will discuss all possible side effects, both short and long-term (including those that have a late effect and may not start immediately), with you before your treatment begins.

One issue that is important to discuss before you undergo treatment is fertility, particularly if you want to have children in the future.

After treatment for upper tract urothelial carcinoma (especially surgery), you may need to adjust to changes in the digestion of food or bladder and bowel function. These changes may be temporary or ongoing, and may require specialised help. If you experience problems, talk to your GP, specialist doctor, specialist nurse or dietitian.

Common side effects may include:

- Surgery – Mild bleeding and discomfort after surgery, the risk of infection, urine leaks or problems urinating after surgery, blockage of food and stools from adhesions from scar tissue, pain, blood clots, weak muscles (atrophy), hernias.

- Chemotherapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, bowel issues such as diarrhoea, hair loss, mouth sores, skin and nail problems, increased risk of infections, loss of fertility, early menopause.

- Radiation therapy – Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, bowel issues such as diarrhoea, skin problems, loss of fertility, early menopause.

Life after treatment

Once your treatment has finished, you will have regular check-ups to monitor how you are recovering after treatment and to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back.

Ongoing surveillance for upper tract urothelial cancer involves a schedule of tests, scans, scopes and physical examinations. Let your doctor know immediately of any health problems between visits.

If your surgery has left you with only one kidney, you will need to limit the amount of salt and protein in your diet, avoid playing contact sport (such as football and boxing), avoid taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as aspirin and ibuprofen), and avoid dyes used in some imaging tests. Your doctor will discuss these issues with you.

Some cancer centres work with patients to develop a “survivorship care plan” which usually includes a summary of your treatment, sets out a clear schedule for follow-up care, lists any symptoms to watch out for and possible long-term side effects, identifies any medical or emotional problems that may develop and suggests ways to adopt a healthy lifestyle going forward. Maintaining a healthy body weight, eating well and being physically active are all important.

If you don’t have a care plan, ask your specialist for a written summary of your cancer and treatment and make sure a copy is given to your GP and other health care providers.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people, cancer may come back at some stage after treatment. This is known as a recurrence. If you have had cancer of the ureter or renal pelvis, you may have an increased risk of developing a bladder cancer after a few years. If the cancer does come back, treatment will depend on where the cancer has returned in your body and may include a mix of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment. Palliative care and treatment can be provided in the home, in a hospital, in a palliative care unit or hospice, or in a residential aged care facility. Services may vary because palliative care is different in each state and territory.

When cancer is no longer responding to active treatment, it can be difficult to think about how and where you want to be cared for towards the end of life. But it’s essential to talk about what you want with your family and health professionals, so they know what is important to you. Your palliative care team can support you in having these conversations.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people are able to get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.