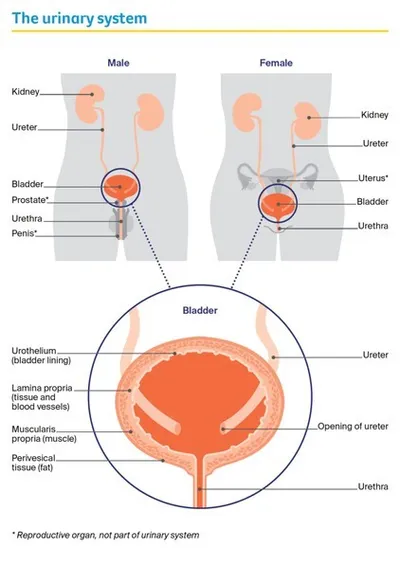

The bladder

The bladder is a hollow, muscular sac that stores urine (wee or pee). It sits behind the pubic bone in the pelvis, and is part of the urinary system.

The urinary system also includes 2 kidneys, 2 tubes called ureters that lead from the kidneys into the bladder, and another tube called the urethra that leads out of the bladder. In males, the urethra is a long tube that passes through the prostate and down the penis. In females, the urethra is shorter and opens in front of the vagina (birth canal).

The kidneys produce urine, which travels to the bladder through the ureters. The bladder is like a balloon and expands as it fills with urine. A layer of muscle wraps around the urethra and works like a valve to keep the bladder closed and stop leaking of urine. When you are ready to empty your bladder, the bladder muscle tightens and the valves open, and urine passes through the urethra and out of the body.

Layers of the bladder wall

There are 4 main layers of tissue in the bladder.

|

urothelium |

The inner layer. It is lined with cells called urothelial cells that stop urine being absorbed into the body. |

|

lamina propria |

The layer of tissue and blood vessels that surrounds the urothelium. |

|

muscularis propria |

The thickest layer. It consists of muscle that tightens to empty the bladder. |

|

perivesical tissue |

The outer layer. Mostly made up of fatty tissue, it separates the bladder from nearby organs. |

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about bladder cancer are below.

What is bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer begins when cells in the inner lining of the bladder (urothelium) become abnormal. This causes the cells to grow and divide out of control. As the cancer grows, it may start to spread into the deeper layers of the bladder wall. Some cancer cells can also break off and travel outside the bladder to other parts of the body (e.g. lymph nodes, lungs, bones or liver).

What are the main types?

There are 3 main types of bladder cancer. They are named after the cells they start in.

Urothelial carcinoma

- starts in the urothelial cells lining the bladder wall

- most common type (80–90% of all bladder cancers)

- also called transitional cell carcinoma or TCC

- includes 2 rarer subtypes (plasmacytoid and micropapillary), which are more aggressive

Squamous cell carcinoma

- starts in thin, flat squamous cells in the bladder lining

- accounts for 1–2% of all bladder cancers

- more likely to be invasive

Adenocarcinoma

- develops from the glandular cells in the bladder

- makes up about 1% of all bladder cancers

- usually invasive

There are also rarer types of bladder cancer. These include sarcomas, which start in the muscle, and an aggressive form called small cell carcinoma.

Urothelial carcinoma occasionally starts in a ureter or part of a kidney. This is known as upper tract urothelial cancer. For information about how this cancer is diagnosed and treated, see our Understanding Upper Tract Urothelial Cancer fact sheet.

How common is bladder cancer?

Each year, about 3100 Australians are diagnosed with bladder cancer. Most people diagnosed with bladder cancer are aged 60 or older, but it can occur at any age.

About 1 in every 140 males will be diagnosed with bladder cancer before age 75, making it 1 of the 10 most common cancers in males. For females, the risk is about 1 in 560, although it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage.

What are the symptoms?

Sometimes bladder cancer doesn’t have many symptoms and is found when a urine test is done for another reason. However, most people with bladder cancer do have some symptoms. These can include:

Blood in the urine (haematuria) – This is the most common symptom of bladder cancer. It often happens suddenly but is usually not painful. There may be only a small amount of blood in the urine, and it may look red or brown. The blood may come and go, or it may appear only once or twice.

Changes in bladder habits – Changes may include a burning feeling when urinating (weeing or peeing), needing to pass urine more often or urgently, not being able to urinate when you feel the urge, and pain while urinating.

Other symptoms – Less commonly, people may have pain in one side of their lower abdomen (belly) or back. They may also lose their appetite and lose weight.

Not everyone with these symptoms has bladder cancer, but if you have any of these symptoms or are concerned, see your doctor as soon as possible.

Never ignore blood in your urine. If you notice any blood in your urine, see your doctor and arrange to see a specialist to have your bladder examined. The earlier bladder cancer is detected, the easier it is to treat.

What are the risk factors?

Research shows that people with certain risk factors are more likely to develop bladder cancer. Risk factors include:

- Smoking – People who smoke are up to 3 times more likely than non-smokers to develop bladder cancer.

- Older age – About 90% of people diagnosed with bladder cancer in Australia are aged over 60.

- Being male – Men are about 3 times more likely than women to develop bladder cancer.

- Chemical exposure at work – Chemicals called aromatic amines, benzene products and aniline dyes are linked to bladder cancer. These chemicals are used in rubber and plastics manufacturing, in the dye industry, and sometimes in the work of painters, machinists, printers, hairdressers, firefighters and truck drivers.

- Parasitic bladder infections – One of the rarer types of bladder cancer (squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder) has been linked to a parasitic bladder infection called schistosomiasis. This is very rare in people born in Australia; it is caused by a parasite found in fresh water in Africa, Asia, South America and the Caribbean.

- Long-term catheter use – Using urinary catheters over a long period may be linked with squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.

- Previous cancer treatments – These include the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide and radiation therapy to the pelvic area.

- Diabetes treatment – The diabetes drug pioglitazone can increase the risk of bladder cancer.

- Personal or family history – Most people with bladder cancer do not have a family history. However, having one or more close blood relatives diagnosed with bladder cancer, or having inherited a gene linked to bladder cancer, slightly increases the risk of bladder cancer.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your general practitioner (GP) will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist (a urologist), who will arrange further tests.

If bladder cancer is diagnosed, the urologist will consider treatment options. They will often discuss your treatment options with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Health professionals you may see

- Urologist/Urological surgeon – diagnoses and treats diseases of the urinary systems, as well as disorders in the male reproductive system; performs surgery

- Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy

- Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

- Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC)

- Nurse – provides care, information and support throughout treatment and administers drugs

- Urological nurse – a urology nurse specialist provides specialist nursing care to people with diseases of the urinary system – they may conduct assessments, administer treatments and provide information and support

- Continence nurse – assesses and educates patients about bladder and bowel control

- Stomal therapy nurse – provides information about surgery and can help you adjust to life with a stoma

- Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

- Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

- Physiotherapist – helps with restoring movement and mobility; a continence physiotherapist provides exercises to help strengthen pelvic floor muscles and improve bladder and bowel control

- Exercise physiologist – prescribes exercise to help improve your overall health, fitness, strength and energy levels

- Psychologist, Counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

How is bladder cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor suspects you have bladder cancer, they will examine you and arrange tests. The tests may include:

- general tests to check your overall health

- tests to find cancer

- further tests to see if the cancer has spread (metastasised).

Some tests may be repeated during and after treatment to see how the treatment is working. If you feel anxious waiting for test results, it may help to talk to a friend or family member, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

General tests

The first tests you have may be an internal examination and blood and urine tests. Sometimes you won’t need an internal examination until after bladder cancer has been diagnosed.

Internal examination

As the bladder is close to the rectum and vagina, your doctor may do an internal examination by inserting a gloved finger into the rectum or vagina to feel for anything unusual. Some people find this test embarrassing or uncomfortable, but it takes less than a minute.

Blood and urine tests

Your doctor may take blood samples to check your overall health. You will also be asked for a urine sample, which will be checked for blood and bacteria (called urinalysis). If you have blood in your urine, you may need to collect samples of your urine over 3 days. These samples will be checked for cancer cells (called urine cytology).

Tests to find cancer in the bladder

The main test to look for bladder cancer is a cystoscopy. This procedure lets your doctor look closely at the bladder lining (urothelium). Other tests can also give your doctors information about the cancer. These may include an ultrasound before the cystoscopy, a tissue sample (biopsy) taken during a cystoscopy, and a CT or MRI scan.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound uses soundwaves to create a picture of the bladder. This scan is used to show if cancer is present and how large it is, but an ultrasound can’t always find small tumours.

Your medical team will usually ask you to drink lots of water before the ultrasound so you have a full bladder. This makes the bladder easier to see on the scan. After the first scan, you will go to the toilet and empty your bladder, then the scan will be repeated.

During an ultrasound, you will lie on a bench and uncover your abdomen (belly). A cool gel will be spread on your skin, and a small handheld device called a transducer will be moved across your abdominal area. The transducer creates soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or tumour. A computer turns the soundwaves into a picture. Having an ultrasound is painless and usually takes 15–20 minutes. Not all people will have an ultrasound. Sometimes, a CT scan is the first scan you will have.

CT scan

A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-rays and a computer to create a detailed picture of the inside of the body. A scan of the urinary system may be called a CT urogram, CT IVP (intravenous pyelogram) or a triple-phase abdomen and pelvis CT – these are different names for the same test. Some people have a CT scan of other areas of the body to see if the cancer has spread.

CT scans are usually done at a hospital or a radiology clinic. When you make the appointment for the scan, you will be given instructions to follow about what you can eat and drink before the scan.

As part of the procedure, a dye (the contrast) is injected into one of your veins. The dye travels through your bloodstream to the kidneys, ureters and bladder, and helps show up abnormal areas more clearly.

The scan is usually done 3 times: once before the dye is injected, once immediately afterwards, and then again a short time later. The dye may make you feel hot all over and cause some discomfort in the abdomen and a feeling of having passed urine. Symptoms should ease quickly but tell the person doing the scan if you feel unwell.

During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table that moves in and out of the scanner, which is large and round like a doughnut. The whole procedure takes 30–45 minutes.

MRI scan

Less commonly, your doctors may recommend an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to check for bladder cancer. This scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional pictures of organs in your abdomen.

Before the scan, let your medical team know if you have a pacemaker or any other metallic object in your body. If you do, you may not be able to have an MRI scan, although some newer devices are safe to go into the scanner. Also ask what the MRI will cost, as Medicare usually does not cover this scan for bladder cancer.

Before the MRI, you may be injected with a dye to help make the pictures clearer. You will then lie on an examination table inside a large metal tube that is open at both ends. The scan is painless, but the noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you could become distressed, mention this to your medical team. You may be given a mild sedative to help you relax. The MRI scan takes 30–90 minutes.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to contrast (dye) during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Cystoscopy

The next test is often a cystoscopy. This is done using a cystoscope (a thin tube with a light and camera on the end), which will be either flexible or rigid (a tube that does not bend). A flexible cystoscopy allows the doctor to see if there is a tumour, while a rigid cystoscopy or transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) is needed to remove a tumour. If the initial scans suggest there may be a tumour, you will usually have a rigid cystoscopy.

Flexible cystoscopy – This procedure is done under a local or general anaesthetic, with a gel squeezed into the urethra to numb the area. The cystoscope is put through your urethra and into the bladder. The camera projects images onto a monitor so the doctor can see inside the bladder. A flexible cystoscopy usually takes only a few minutes. For several days after the procedure, you may see some blood in your urine and feel mild discomfort when urinating.

Rigid cystoscopy and biopsy – This is done in hospital under general anaesthetic, usually as a day procedure. It takes about 30 minutes.

The cystoscope is put through your urethra into the bladder. If a small tumour is found, the doctor will put some instruments into the cystoscope and remove a sample of tissue. This will be tested for signs of cancer (a biopsy). The biopsy results are usually available in 5–7 days. If a larger tumour is found, you may have a procedure called a transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT).

After the cystoscopy, you may have some urinary symptoms, such as going to the toilet frequently and/or urgently, or even having trouble controlling your bladder (incontinence). These symptoms will usually settle in a few hours. Keep drinking fluids and stay near a toilet.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT)

This procedure is done in hospital under general anaesthetic and takes up to 45 minutes. In some cases, a TURBT may be the only procedure needed to treat the cancer.

How TURBT is done – The rigid cystoscope is passed through the urethra into the bladder so the surgeon can see the inside of your bladder on a monitor. The surgeon may remove the tumour through the urethra using a wire loop on the end of the cystoscope. Other methods for destroying the cancer cells include burning the base of the tumour with an electrical current (fulguration) or using a high-energy laser. A TURBT does not involve any cuts to the outside of the body.

The removed tissue will be examined for signs of cancer. Results are usually available in 5–7 days.

What to expect after a TURBT

Most people who have a TURBT stay in hospital for 1–2 days. Your body needs time to recover and heal after the surgery.

Having a catheter – You may have a thin, flexible tube (catheter) put in your bladder to drain your urine into a bag. The catheter may be connected to a system that uses saline (salt water) to wash the blood and blood clots out of your bladder. This is called bladder irrigation. When your urine looks clear, the catheter will be removed and you will be able to go home. If the tumour is small, you may not need a catheter and you may be discharged from hospital on the

same day.

Recovery at home – When you go home, avoid any heavy lifting or vigorous exercise for about 3–4 weeks. If you were taking blood-thinning drugs before the procedure, talk to your doctor about when you can restart them.

Side effects – Side effects may include blood in the urine, passing urine more often and bladder infections. It is normal to see some blood in your urine for up to 2 weeks. Talk to your doctor if you have any concerns.

Flushing the body – It is important to drink lots of water to flush the bladder of blood and keep the urine clear.

When to get help – Contact your medical team immediately if you feel cold, shivery, hot or sweaty; have burning or pain when urinating; need to urinate often and urgently; pass blood clots; or have difficulty passing urine.

Further tests

You may need other imaging tests such as a radioisotope bone scan, x-ray or PET–CT scan to show if and how far the cancer has spread.

Radioisotope bone scan

A radioisotope scan is used to see whether the cancer has spread to the bones. It may be called a whole-body bone scan (WBBS) or a bone scan.

Before you have the scan, a tiny amount of radioactive dye is injected into a vein, usually in your arm. You will need to wait for a few hours while the dye moves through your bloodstream to your bones. The dye collects in areas of abnormal bone growth. Your body will be scanned with a machine that detects radioactivity. A larger amount of radioactivity will show up in any areas of bone affected by cancer cells.

The scan is painless and takes less than an hour. Afterwards, you need to drink plenty of fluids and urinate frequently to flush the radioactive dye from your body. This usually takes a few hours. You should avoid being around young children and pregnant women for the rest of the day.

X-rays

You may need x-rays if a particular area looks abnormal in other tests or is causing symptoms. A chest x-ray can check the health of your lungs and look for signs the cancer has spread. Sometimes, people will have a CT scan instead of an x-ray.

PET–CT scan

A PET (positron emission tomography) scan combined with a CT scan is a specialised imaging test. It can sometimes be used to find bladder cancer that has spread to lymph nodes or other areas of the body that may not be picked up on a CT scan.

Clinic staff will tell you how to prepare for a PET–CT scan, particularly if you have diabetes. Before the scan, you will be injected with a glucose solution containing a small amount of radioactive material. Cancer cells show up brighter on the scan because they take up more glucose solution than normal cells do. You will be asked to sit quietly for 30–90 minutes as the glucose moves through your body, then you will be scanned.

Staging bladder cancer

The tests described above help show whether you have bladder cancer, how far the cancer has grown into the layers of the bladder, and if the cancer has spread outside the bladder. This is called staging. The staging system most commonly used is the TNM system, which stands for tumour-node-metastasis. Using this information, the doctor may describe the cancer as:

Superficial bladder cancer – This is also called non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer or NMIBC. The cancer cells are found only in the inner lining of the bladder (urothelium) or the next layer of tissue (lamina propria) and haven’t grown into the deeper layers of the bladder wall.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) – The cancer has spread beyond the urothelium and lamina propria into the layer of muscle (muscularis propria), or sometimes through the bladder wall into the surrounding fatty tissue. MIBC can also sometimes spread to lymph nodes close to the bladder.

Advanced bladder cancer – The cancer has spread (metastasised) outside of the bladder into distant lymph nodes or other organs of the body.

TNM staging system

The most common staging system for bladder cancer is the TNM system. In this system, letters and numbers are used to describe the cancer, with higher numbers indicating larger size or spread.

|

T stands for tumour |

Ta, Tis and T1 are superficial bladder cancer, while T2, T3 and T4 are muscle-invasive bladder cancer. |

|

N stands for nodes |

N0 means the cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes; N1, N2 and N3 indicate it has spread to lymph nodes. NX means it is unknown. |

|

M stands for metastasis |

M0 means the cancer has not spread to distant parts of the body; M1 means it has spread to distant parts of the body. MX means it is unknown. |

Some doctors put the TNM scores together to produce an overall stage, from stage 1 (earliest stage) to stage 4 (most advanced).

Grade and risk category

The biopsy and/or TURBT results will show the grade of the cancer. This is a score that describes how quickly a cancer might grow.

Knowing the grade helps your urologist predict how likely the cancer is to come back (recur) or grow into deeper layers (progress), and if you will need further treatment after surgery. The grade may be described as:

Low grade – The cancer cells look similar to normal bladder cells and are usually slow-growing. They are less likely to invade and spread.

High grade – The cancer cells look very abnormal and grow quickly; they are more likely to spread both into the bladder muscle and outside the bladder.

In superficial bladder cancers, the grade may be low or high, while almost all muscle-invasive cancers are high grade. Carcinoma in situ (stage Tis in the TNM system) is a high-grade tumour that needs to be treated quickly to prevent it invading the muscle layer.

Risk category – Based on the stage, grade and other features, a superficial bladder cancer will also be classified as having a lower or higher risk of returning after treatment or spreading into the muscle layer. Knowing the risk category will help your doctors work out which treatments to recommend.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

In general, the earlier bladder cancer is diagnosed, the better the outcome. To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- your test results

- the type of bladder cancer

- the stage, grade and risk category

- how well you respond to treatment

- other factors such as your age, fitness and medical history.

Treatment for bladder cancer

Superficial bladder cancer treatment

If cancer cells are found only in the inner layers of the bladder, the cancer is called superficial or non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

The main treatment for superficial bladder cancer is surgery to remove the cancer. This is often done during diagnosis. Surgery is commonly combined with chemotherapy or immunotherapy, which is delivered directly into the bladder (intravesical).

Surgery (TURBT)

Most people with superficial bladder cancer have an operation called transurethral resection of bladder tumour or TURBT. This procedure is usually done during diagnosis.

If the cancer has spread to the lamina propria or is high grade, you may need a second TURBT 2–6 weeks after the first procedure to make sure that all cancer cells are removed. If the cancer comes back after initial treatment, your surgeon may do another TURBT or suggest removing the bladder in an operation called a cystectomy.

Check-ups after surgery

Cancer can come back even after a TURBT has removed it from the bladder. You will need regular follow-up cystoscopies to find any new tumours in the bladder as early as possible. This approach is known as surveillance cystoscopy.

How often you need to have a cystoscopy will depend on the stage and grade of the cancer, and how long since it was diagnosed.

Intravesical chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells.

Chemotherapy drugs are usually injected into a vein or given as tablets. In intravesical chemotherapy, the drugs are put directly into the bladder using a catheter (a thin, flexible tube) inserted through the urethra.

Intravesical chemotherapy is used mainly for low-risk to medium-risk superficial bladder cancer. It helps prevent the cancer coming back (called a recurrence).

Each dose is called an instillation, and this is usually given in a day procedure in hospital.

People with a low risk of recurrence usually have one instillation straight after TURBT surgery. The chemotherapy solution is left in the bladder for 1–2 hours and then drained out through a catheter or by urinating after the catheter has been removed. You may be asked to change position every 15 minutes so the solution washes over the whole bladder.

People with a medium risk of recurrence may have instillations once a week for 6 weeks. While you are having a course of intravesical chemotherapy, your doctor may advise you to use contraception.

Side effects of intravesical chemotherapy – Because intravesical chemotherapy puts the drugs directly into the bladder, it has fewer side effects than systemic chemotherapy (when the drugs spread through the whole body).

The main side effect of intravesical chemotherapy is inflammation of the bladder lining (called cystitis). Signs of cystitis include wanting to pass urine more often or having a burning feeling when urinating. Drinking plenty of fluids can help. If you develop a bladder infection, your doctor can prescribe antibiotics.

In some people, intravesical chemotherapy may cause a rash on the hands or feet. Tell your doctor if you notice any side effects while on intravesical chemotherapy.

Intravesical immunotherapy (BCG)

Immunotherapy is treatment that uses the body’s own natural defences (immune system) to fight disease. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is a vaccine that was originally used to prevent tuberculosis. It can also stimulate a person’s immune system to stop or delay bladder cancer coming back or becoming invasive.

The most effective way to treat high-risk superficial bladder cancer is with a combination of BCG and TURBT. BCG is given once a week for 6 weeks, starting 2–4 weeks after TURBT surgery. It is put directly into the bladder through a catheter.

You may be asked to change position every 15 minutes so the vaccine washes over the whole bladder. This is usually done as a day procedure in hospital, and each treatment session takes up to 2 hours.

The BCG vaccine contains live bacteria, which can harm healthy people, so your treatment team will tell you what safety measures to follow at home. Speak to your medical team if you have any questions.

Let your doctor know of any other medicines or complementary therapies you are using, as they may interfere with how well the bladder cancer responds to BCG. For example, the drug warfarin (a blood thinner) is known to interact with BCG.

BCG safety at home

Take care going to the toilet – For 6 hours after BCG treatment, sit on the toilet when urinating to avoid splashing. When finished, pour 2 cups of household bleach (or a sachet of sodium hypochlorite if provided by your treatment team) into the toilet bowl. Wait 15 minutes before flushing twice with the toilet lid closed. Wipe the seat with disinfectant. If clothing is splashed with urine, wash separately in bleach and warm water.

Drink fluids – To help clear the BCG from your body, drink plenty of liquids for 6–8 hours after treatment.

Handle incontinence pads carefully – If you use incontinence pads, for a few days after treatment take care when disposing of them. Pour bleach on the used pad, allow it to soak in, then place the pad in a plastic bag. Tie up the bag and put it in your rubbish bin. You may also be able to take the sealed bag back to the hospital or treatment centre for disposal in a biohazard bin.

Practise safe sex – For a week after each treatment, use barrier contraception (condoms) to protect your partner from any BCG that may be present in your body fluids and to prevent pregnancy.

Wash hands well – For a few days after each treatment, wash your hands extra well after going to the toilet. If your skin comes in contact with urine, wash or shower with soap and water.

Ongoing BCG treatment

For most people with high-risk superficial bladder cancer, the initial, 6-week course of BCG treatments is followed by more BCG. This is called maintenance BCG and it reduces the risk of the disease coming back or spreading.

Maintenance treatment can last for 1–3 years, but treatment sessions become much less frequent (e.g. one dose a month). Treatment schedules can vary so ask your doctor for further details.

Let your doctor know of any other medicines or complementary therapies you are using, as they may interfere with how well the bladder cancer responds to BCG. For example, the drug warfarin (a blood thinner) is known to interact with BCG.

Side effects of BCG – Common side effects of BCG include needing to urinate more often; burning or pain when urinating; blood in the urine; a mild fever; and tiredness. These side effects usually last a couple of days after each BCG treatment session.

Less often, the BCG may spread through the body and can affect any organ. If you develop flu-like symptoms, such as fever over 38°C that lasts longer than 72 hours, pain in your joints, a cough, a skin rash, tiredness, or yellow skin (jaundice), contact a nurse or doctor at your treatment centre immediately. A BCG infection can be treated with medicines.

Very rarely, BCG can cause infections in the lungs or other organs months or years after treatment. If you are diagnosed with an infection in the future, it is important to tell the doctor that you had BCG treatment.

BCG safety at home

Take care going to the toilet – For 6 hours after BCG treatment, sit on the toilet when urinating to avoid splashing. When finished, pour 2 cups of household bleach (or a sachet of sodium hypochlorite if provided by your treatment team) into the toilet bowl. Wait 15 minutes before flushing twice with the toilet lid closed. Wipe the seat with disinfectant. If clothing is splashed with urine, wash separately in bleach and warm water.

Drink fluids – To help clear the BCG from your body, drink plenty of liquids for 6–8 hours after treatment.

Handle incontinence pads carefully – If you use incontinence pads, for a few days after treatment take care when disposing of them. Pour bleach on the used pad, allow it to soak in, then place the pad in a plastic bag. Tie up the bag and put it in your rubbish bin. You may also be able to take the sealed bag back to the hospital or treatment centre for disposal in a biohazard bin.

Practise safe sex – For a week after each treatment, use barrier contraception (condoms) to protect your partner from any BCG that may be present in your body fluids and to prevent pregnancy.

Wash hands well – For a few days after each treatment, wash your hands extra well after going to the toilet. If your skin comes in contact with urine, wash or shower with soap and water.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer treatment

When bladder cancer has invaded the muscle layer (muscularis propria), the main treatment options are:

- surgery to remove the whole bladder (cystectomy), sometimes with chemotherapy given before or after the surgery

- bladder-conserving surgery (TURBT), followed by radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. This is called trimodal therapy.

Surgery (cystectomy)

Some people with muscle-invasive disease have surgery to remove the bladder (cystectomy). This may also be recommended for high-risk superficial bladder cancer (also called non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer or NMIBC) that has not responded to BCG. The surgeon usually needs to remove the whole bladder and nearby lymph nodes. This is called a radical cystectomy.

How the surgery is done – Surgery to remove the bladder (called a cystectomy) and create a urinary diversion is a complicated operation.

Different surgical methods may be used to remove the bladder:

- Open surgery makes one long cut (incision) in the lower abdomen. A cut is usually made from below the bellybutton to the pubic area.

- Keyhole surgery, also known as minimally invasive or laparoscopic surgery, makes several smaller cuts in the abdomen. Instruments are inserted through the cuts, sometimes with help from a robotic system.

It is important to have this surgery in a specialised centre with a surgeon who does a lot of cystectomies. In general, having an experienced surgeon is more important than the type of surgery. Talk to your surgeon about the pros and cons of each surgical method, and check what you’ll have to pay. Unless you are treated as a public patient in a public hospital, you are likely to have lots of costs not covered by Medicare or your health fund.

What to expect after surgery

When you wake up after the operation, you will be in a recovery room near the operating theatre. Once you are fully conscious, you will be moved to intensive care or to the ward.

Tubes and drips – You may have an intravenous (IV) drip to give you fluid and medicine, and a tube in your abdomen to drain fluid from the operation area. These will be removed as you recover.

Pain and discomfort – After a major operation, it is common to feel some pain. You will be given pain medicine as a tablet (orally), through a drip (intravenously) or through a catheter inserted in the spaces in the spine (epidural) or along the wound (wound catheters). If you still have pain, let your doctor or nurse know and they may change your medicine.

Recovery time – You will probably be in hospital for 1–2 weeks, but it can take 6–8 weeks to fully recover from a cystectomy. The recovery time will depend on the type of surgery, your fitness and whether you have any complications.

Passing urine – Because a radical cystectomy removes the whole bladder, the surgeon needs to create a new way for your body to store and pass urine.

Surgery to remove the bladder

The most common operation for muscle-invasive bladder cancer is a radical cystectomy. The surgeon removes the whole bladder and nearby lymph nodes. Other organs may also be removed. After a radical cystectomy, a urinary diversion is needed so your body can store and pass urine.

Sexual activity and fertility after cystectomy

A cystectomy can affect sexual activity and fertility in many ways. You may find these changes upsetting and worry about how they’ll affect your relationships. Ask your treatment team for information about ways to manage these changes. It may be helpful to talk about how you’re feeling with your partner, family members or a counsellor.

Changes for males

Nerve damage to the penis – A cystectomy can often damage nerves to the penis, but the surgeon will try to prevent or minimise this. Nerve damage can make it difficult to get an erection. Options for improving erections include:

- oral medicines prescribed by a doctor that increase blood flow to the penis

- injections of medicine into the penis

- vacuum devices that use suction to draw blood into the penis and make it firm

- an implant called a penile prosthesis – under general anaesthetic, flexible rods or thin inflatable cylinders are inserted into the penis and a pump is placed in the scrotum; you can then turn on or squeeze the pump when you want an erection.

Orgasm changes – If the prostate and seminal vesicles are removed along with the bladder, you will not be able to ejaculate after a radical cystectomy. You can still feel the muscular spasms and pleasure of an orgasm even if you cannot ejaculate or get an erection, but it will be a dry orgasm because you no longer produce semen.

Fertility changes – If the prostate and seminal vesicles are removed, you will no longer produce semen. This means you won’t be able to have children naturally. If you might want to have children in the future, talk to your treatment team about whether you can store sperm at a fertility clinic before treatment. The sperm could then be used when you are ready to start a family.

Changes for females

Vaginal changes – Sometimes, the vagina may be shortened or narrowed during a cystectomy. Nerves that help keep the vagina moist can also be affected, making the vagina dry. These changes can make penetrative sex difficult or uncomfortable at first. Ways to manage these changes include:

- using a hormone cream (available on prescription) or vaginal moisturiser (available at pharmacies) to keep your vagina moist

- asking a physiotherapist how to use vaginal dilators to help stretch the vagina – vaginal dilators are plastic or rubber tube-shaped devices that come in different sizes

- when you feel ready, trying to have sex regularly and gently to stretch the vagina

- using a water-based or silicone-based lubricant (available from pharmacies and supermarkets) to make sex more comfortable.

Arousal changes – A cystectomy can damage the nerves in the vagina or reduce the blood supply to the clitoris, which can affect how you become aroused and your ability to orgasm. Talk to your surgeon or nurse about ways to minimise potential side effects. You can also try exploring other areas of your body that feel pleasurable when touched, such as the breasts, inner thighs, feet or buttocks.

Menopause and fertility – Sometimes, the uterus and other reproductive organs are removed during a radical cystectomy. This will cause menopause if you have not already been through it. Your periods will stop, you will no longer be able to become pregnant, and you may have menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes and vaginal dryness. Talk to your doctors about ways to deal with symptoms of menopause.

Systemic chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells.

For muscle-invasive bladder cancer, drugs are injected into a vein (intravenously). As the drugs circulate in the blood, they travel throughout the body. This type of chemotherapy is called systemic chemotherapy. It is different to the intravesical chemotherapy used for superficial bladder cancer, which is delivered directly into the bladder.

Systemic chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer is used:

- before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) – to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove; it can also lower the risk of the cancer coming back

- after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) – if there is a high risk of the cancer coming back.

How chemotherapy is given – You will see a medical oncologist to plan your chemotherapy treatment. Chemotherapy is commonly given as a period of treatment followed by a break. This is called a cycle. In most cases, you will have several cycles of chemotherapy over a few months. Usually, a combination of drugs works better than one drug alone. The drugs you are offered will depend on your age, fitness, kidney function and personal preference.

Systemic chemotherapy can sometimes be combined with radiation therapy (chemoradiation) and surgery as part of trimodal therapy. Systemic chemotherapy may also be used for bladder cancer that has spread to other parts of the body.

Side effects of systemic chemotherapy – These may include: fatigue; nausea and vomiting; constipation; mouth sores; taste changes; itchy skin; hair loss; ringing in the ears; and tingling or numbness of the fingers or toes. Side effects usually last for only a few weeks or months, although some can be permanent. Talk to your doctor about ways to reduce your risk or manage any side effects you develop.

During chemotherapy, you may be more prone to infections. If you develop a temperature over 38°C, contact your doctor or go immediately to the emergency department at your nearest hospital.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy, also called radiotherapy, uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is usually in the form of x-ray beams. Radiation therapy to treat bladder cancer may be used on its own, combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) or as part of trimodal therapy.

How radiation therapy is given – You will meet with the radiation oncology team to plan your treatment. It is common to have more imaging scans to help pinpoint the area to receive the radiation. During a treatment session, you will lie on an examination table and a machine will direct the radiation towards your bladder. The treatment is painless.

Side effects of radiation therapy – Temporary side effects may include: needing to urinate more often and more urgently; a burning sensation when you urinate; fatigue; loss of appetite; diarrhoea; and soreness around the anus. Symptoms tend to build up during treatment and usually start improving a few weeks after treatment ends.

Less commonly, radiation therapy may permanently affect the bowel or bladder. Bowel motions may be more frequent and looser, and damage to the bladder lining (radiation cystitis) can cause blood in the urine.

Radiation therapy for males may cause poor erections and make ejaculation uncomfortable for some months after treatment. For females, radiation therapy can cause the vagina to become drier, narrower and shorter.

Radiation therapy may also lead to premature menopause. In addition, if the therapy affects the lymph nodes, there may be an increased risk of lymphoedema (swelling in the legs caused by a build-up of lymph fluid).

Trimodal therapy

Instead of a cystectomy, you may have trimodal therapy as the main treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Trimodal therapy may be used if a person is unable to have surgery to remove the bladder or would prefer to keep their bladder. It is most suited for people whose bladder is working well and who have smaller cancers that haven’t spread. Trimodal therapy involves:

- surgery to remove the tumour from the bladder (TURBT)

- after surgery, radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) to destroy remaining cancer cells. People who are not fit enough for chemotherapy will have radiation therapy on its own.

Studies have shown that trimodal therapy has similar outcomes to radical cystectomy for certain small cancers. However, there is a chance the cancer may come back in the bladder and cystectomy may still be required. Talk to your medical team to discuss whether trimodal therapy may be an option for you.

Having trimodal therapy

If you have trimodal therapy, chemotherapy or other medicines are given to make the cancer cells more sensitive to radiation, which can increase the success of the treatment. You will usually have radiation therapy as daily treatments, Monday to Friday, over 4–7 weeks as an outpatient.

There are different options for receiving chemotherapy. Some people will have chemotherapy once a week a few hours before or after a radiation therapy session. Other people take a tablet or have an infusion over several days.

During and after chemoradiation, you may experience side effects from both the chemotherapy and the radiation therapy. Talk to your treatment team about ways to manage the side effects of chemoradiation.

The bladder is not removed in trimodal therapy, so you can still urinate in the usual way. You will need to have regular cystoscopies after treatment to check that the cancer has not come back.

Urinary diversions

If you have surgery to remove the bladder (radical cystectomy), you will need another way to collect and store urine.

This is known as a urinary diversion. It is a major change, and your treatment team will offer support to help you adjust.

Your surgeon will talk to you about the best type of urinary diversion for you. They will recommend one of the following options:

- urostomy – creates a new opening to your urinary system

- neobladder – creates a new bladder from your small bowel

- continent urinary diversion – creates a pouch from your small bowel to hold urine until you are ready to drain it.

Urostomy

Also known as an ileal conduit, a urostomy is the most common type of urinary diversion. In a urostomy, urine will drain into a bag attached to the outside of the abdomen. The surgeon will use a piece of your small bowel (ileum) to create a passageway (conduit). This connects the ureters (the tubes that carry urine from your kidneys) to an opening created in the abdomen. The opening is called a stoma.

How the stoma works

A watertight, drainable bag is placed over the stoma to collect urine. The bag has an adhesive backing that sticks to your abdomen. This small bag is worn under clothing, fills continuously and needs to be emptied several times a day through a tap or bung on the bag. The small bag will be connected to a larger drainage bag at night if required.

Positioning the stoma

Before the operation, the surgeon and/or a stomal therapy nurse will plan where the stoma will go. They will discuss the position with you and aim to place the stoma so it doesn’t move when you sit, stand or move. Sometimes the position can be tailored for particular needs. For example, golfers may prefer the stoma to be placed so that it doesn’t interfere with their golf swing. The stoma will usually be created on the abdomen, to the right of the bellybutton.

Having a stoma

For the first few days after the operation, the stomal therapy nurse will look after the stoma and make sure the bag is emptied and changed as often as necessary.

Once you are ready, the stomal therapy nurse will teach you and/or your carer/family member how to care for the stoma. At first, the stoma will be slightly swollen and it may be several weeks before it settles down. The stoma may also produce a thick, white substance (mucus), which might appear as pale threads in the urine. The amount of mucus will lessen over time, but it won’t disappear completely.

Stents (small plastic tubes) will be used to help with the flow of urine while the ureters heal. These stents are placed at the time of surgery and are temporary. They will be removed before you are discharged from hospital, or up to 3 weeks after surgery. Your surgeon will talk to you about when the stents will be removed.

Attaching the bag – There are different types of bags (sometimes called appliances) and the stomal therapy nurse will help you choose one that suits you. The nurse will show you how to clean your stoma and change the bags. This will need to be done regularly, usually every day while in hospital (for teaching purposes) and every 2–3 days after that. It might be helpful to have a close relative or friend join you when the nurse gives the instructions so they can support you at home.

Emptying the bag – How often you need to empty a bag is affected by how much you drink. Staying hydrated is very important with a urostomy. The first few times you empty the bag, allow yourself plenty of time and privacy so that you can work at your own pace without any interruptions.

Living with a stoma

Having a urostomy is a major change and many people feel overwhelmed at first. It’s natural to worry about how the urostomy will affect your appearance, lifestyle and relationships.

Learning to look after the urostomy may take time and patience. It may sometimes affect your travel plans and social life in the early days while you are gaining confidence, but these issues can be managed with planning. After you learn how to take care of the stoma, you will find you can still do your regular activities.

You may worry about how the bag will look under clothing. Although the urostomy may seem obvious to you, most people won’t know you are wearing a bag unless you tell them about it. Modern bags are usually flat and shouldn’t be noticeable under clothing.

After bladder surgery, you may have some physical changes that affect your sex life. You may worry about being rejected or having sex with your partner. If you meet a new partner during or after treatment, it can be difficult to talk about your experiences, particularly if your sexuality and body image have been affected.

Sexual intimacy may feel awkward at first, but open communication usually helps. Many people find that once they talk about their fears, their partner is understanding and supportive, and they can work together to make sexual activities more comfortable.

Speaking to a counsellor or cancer nurse about your feelings and experiences can be helpful. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to talk to a health professional about your concerns.

Support for people with a stoma

See a stomal therapy nurse – Stomal therapy nurses are trained in helping people with stomas. They will:

- arrange for you to speak with another person living with a stoma

- answer your questions about the surgery and side effects, including the impact on sexual activities and intimacy

- help you adjust to having a stoma and regain your confidence

- assist you with fitting and using urostomy bags

- give you written instructions on caring for your stoma

- provide ongoing care and support once you are home.

Stomal therapy nurses work in many hospitals. Before discharge, the nurse will make sure that you feel comfortable changing the urostomy bag and that you have a supply of bags.

If your hospital doesn’t have a stomal therapy nurse, your treatment team can help you find one. Or you may be able to find a nurse near you by visiting the Australian Association of Stomal Therapy Nurses. Your doctor may also be able to arrange for a community nurse to visit you.

Join a stoma association – Your stomal therapy nurse will usually help you join a stoma association. For a small annual fee, you will be able to get support, free bags and related products. Visit the Australian Council of Stoma Associations.

Register for the Stoma Appliance Scheme – The Australian Government’s Stoma Appliance Scheme (SAS) provides free stoma bags and related products to people who have a stoma. To be eligible, you must have a Medicare card and belong to a stoma association.

Neobladder

In this method, a pouch is created from a portion of your small bowel and placed in the same area as your original bladder. This pouch is called a neobladder. The procedure for creating a neobladder is more complex and takes longer than creating a urostomy. However, you don’t need to have a stoma with a neobladder.

Once the neobladder is created, the surgeon will stitch it into the ureters to collect and store urine from the kidneys. It will also be stitched into the urethra to drain urine from the body. The neobladder will allow you to urinate through your urethra, but it will feel different from urinating with a normal bladder.

Living with a neobladder

It takes time to get used to a new bladder. The neobladder will not have the nerves that tell you when your bladder is full, and you will have to learn new ways to empty it.

The neobladder may produce a thick white substance (mucus), which might appear as pale threads in the urine. The amount of mucus will lessen over time, but it won’t disappear completely.

Discuss any concerns with your nurse, physiotherapist, GP or urologist, and arrange follow-up visits with them.

See a continence nurse or a pelvic health physiotherapist – They will work with you to develop a toilet schedule to train your new bladder. At first, the new bladder won’t be able to hold much urine and you will probably need to empty your bladder every 2–3 hours. This will gradually increase to 4–6 hours, but it may take several months. During that time, the neobladder may leak when full, and you may have to get up during the night to go to the toilet.

Strengthening the pelvic floor muscles before and after surgery will help you control the neobladder. A pelvic health physiotherapist can teach you exercises.

It can sometimes be difficult to fully empty the neobladder using your pelvic floor muscles. If this is an issue, a continence nurse will also teach you how to drain the bladder with a catheter. This is called intermittent self-catheterisation and it should usually be done twice a day to reduce the risk of urinary tract infections.

Ask about the Continence Aids Payment Scheme (CAPS) – This scheme is operated by Services Australia (Medicare) and provides a payment to eligible people who need a long-term supply of continence aids, including catheters for draining the bladder. You can ask the continence nurse if you’re eligible. Visit CAPS or call the CAPS team on 1800 239 309.

Contact the National Continence Helpline – Call 1800 33 00 66 to speak to a nurse continence specialist or visit the Continence Foundation of Australia for more information.

Continent urinary diversion

In this procedure, the surgeon uses a piece of the small bowel to create a pouch inside the body. The pouch is designed so that it does not leak urine, but can be drained by inserting a catheter through a stoma (an opening on the surface of the abdomen). Several times a day you will need to drain the urine by inserting a drainage tube (catheter) through the stoma into the pouch.

This diversion procedure is not commonly used, but may be an option in some circumstances. Your surgeon or nurse will explain the risks and benefits of this procedure, and how to empty urine from the pouch.

Advanced bladder cancer treatment

If bladder cancer has spread to other parts of the body, it is known as advanced or metastatic bladder cancer. Treatment will focus on controlling the cancer and relieving symptoms without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment.

Many people think that palliative treatment is only for people at the end of their life, but it may help people at any stage of advanced bladder cancer. It is about living as comfortably as possible and helping you to maintain your quality of life. Palliative treatments may include:

Immunotherapy (checkpoint inhibitors)

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. BCG is a type of immunotherapy treatment that has been used for many years to treat superficial bladder cancer.

A newer group of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors work by letting the immune system recognise and attack the cancer.

After a course of chemotherapy, some people with advanced bladder cancer may have immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitor drugs such as pembrolizumab or avelumab. These drugs are given directly into a vein through a drip (infusion) and the treatment is repeated every 2–6 weeks. How many infusions you receive will depend on how you respond to the drug.

Side effects of immunotherapy – Like all treatments, checkpoint inhibitors can cause side effects. Because these drugs act on the immune system, they can sometimes cause the immune system to attack healthy cells in any part of the body. This can lead to various side effects including skin rash, diarrhoea, breathing problems, inflammation of the liver, hormone changes, joint pain and temporary arthritis, and other problems. Your doctor will discuss possible side effects with you.

Systemic chemotherapy

Enfortumab vedotin is a new type of chemotherapy. Known as an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), enfortumab vedotin targets a particular protein (called nectin-4) on cancer cells. You do not need to have tests to see if the cancer has this protein before having this drug.

Enfortumab vedotin may be used for people with advanced bladder cancer that has not responded to other types of systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy. It is given in the same way as other types of systemic chemotherapy.

Side effects of enfortumab vedotin – These may include skin rashes; nausea and vomiting; high blood sugar; shortness of breath or trouble breathing; or eye problems such as blurred vision. Let your treatment team know if you notice these or any other side effects.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy can be used when the bladder cancer is advanced or has spread from the bladder to other areas in the body.

Palliative radiation therapy can be used to shrink the cancer in the bladder, to stop bleeding in the bladder and to help with pain that the cancer may be causing. It can also be directed at other parts of the body for symptoms such as pain from cancer that has spread to the bones.

The number of radiation therapy treatments needed ranges from a single treatment to several weeks of daily treatments. Each treatment session takes about 10–15 minutes.

Side effects of radiation therapy – The potential side effects will depend on which part of the body is being treated, but are usually mild.

Palliative care

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The palliative care team will work with your cancer specialists to manage side effects from treatment. The team also provides support to families and carers.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had bladder cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

If there are no signs of cancer after treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any ongoing side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread.

How often you see your doctor will depend on the type of bladder cancer and treatments. During the check-ups, you can discuss how you’re feeling and mention any concerns, and you may have tests such as CT scans and x-rays.

People who still have a bladder will have regular follow-up cystoscopies because this is the best way to find bladder cancer that has come back. The cystoscopy may be done in hospital in the outpatient department under local anaesthetic or in an operating theatre under general anaesthetic. Depending on the stage and grade of the bladder cancer you had, you will need a follow-up cystoscopy every 3–12 months. This may continue for several years or for the rest of your life, but will become less frequent over time. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if bladder cancer returns?

Sometimes bladder cancer does come back after treatment (known as a recurrence). If the cancer recurs and you still have a bladder, the cancer can usually be removed while it is still in the early stages. This will require a cystoscopy under general anaesthetic. If this isn’t possible, your doctor may consider removal of the bladder (cystectomy).

Some people need other types of treatment, such as systemic chemotherapy, immunotherapy or radiation therapy. The treatment you have will depend on the stage, grade and risk category of the cancer, your previous treatment and your preferences.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA also runs a free counselling program.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on

1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.