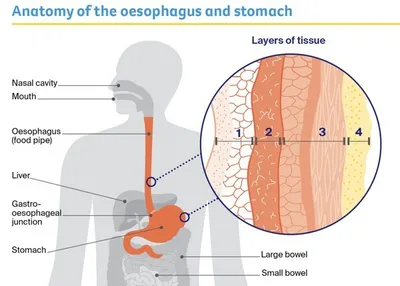

The oesophagus and stomach

The oesophagus and stomach are part of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system.

The digestive system helps the body break down food and turn it into energy.

The oesophagus (food pipe) is a long, muscular tube. The stomach is a hollow, muscular sac-like organ. The top part of the stomach joins to the end of the oesophagus and the other end joins to the beginning of the small bowel.

What the oesophagus and stomach do

The oesophagus moves food, fluid and saliva from the mouth and throat to the stomach. A valve (sphincter) at the lower end of the oesophagus stops acid and food moving from the stomach back into the oesophagus.

The stomach stores food and starts to break it down (digests it). Juices and muscle contractions in the stomach break down food into a thick fluid, which then moves into the small bowel. In the small bowel, nutrients from the broken-down food are absorbed into the bloodstream. The waste moves into the large bowel, where fluids are absorbed into the body and the leftover matter is turned into solid waste (known as faeces, stools or poo).

Layer of tissue

Mucosa (moist innermost layer)

- In the oesophageal wall - made up of squamous cells (thin, flat cells)

- In the stomach wall - made up of glandular cells (column-shaped cells); makes fluids to help break down food, and mucus to protect the stomach lining

Submucosa (supports the mucosa)

- In the oesophageal wall - glands in the submucosa make fluid (mucus); this fluid helps to move food through the oesophagus

- In the stomach wall - provides blood and nutrients to the stomach

Muscle layer

- In the oesophageal wall - known as the muscularis propria; produces contractions to help push food down the oesophagus and into the stomach

- In the stomach wall - known as the muscularis externa; produces contractions to help break down food and push it into the small bowel

Outer layer

- In the oesophageal wall - known as the adventitia; connective tissue that supports the oesophagus

- In the stomach wall - known as the serosa; a smooth membrane that surrounds the stomach

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about stomach and oesophageal cancers are below.

What is stomach cancer?

Stomach cancer develops when cells in any part of the stomach grow and divide in an abnormal way. Tumours can begin anywhere in the stomach, although most start in the stomach’s inner layer (mucosa). This type of cancer is called adenocarcinoma of the stomach, or gastric cancer.

If it is not found and treated early, stomach cancer can spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body, such as the liver and lungs. It may also spread to the lining of the wall of the abdomen (peritoneum). Rarely, it can grow through the stomach wall into nearby organs such as the pancreas and bowel.

Some cancers start at the point where the stomach meets the oesophagus (called the gastro-oesophageal junction). Depending on the location of the gastro-oesophageal cancer, it may be treated similarly to stomach cancer or oesophageal cancer.

How common is stomach cancer?

About 2580 people are diagnosed with stomach cancer in Australia each year. Men are almost twice as likely as women to be diagnosed with stomach cancer. It is more common in people over 60, but it can occur at any age.

What are the symptoms of stomach cancer?

Stomach cancer may not cause symptoms in the early stages. Common symptoms are listed below.

These symptoms can also be caused by many other conditions and do not necessarily mean that you have cancer. Speak with your general practitioner (GP) if you are concerned.

Common symptoms of stomach cancer

- weight loss or loss of appetite

- difficulty swallowing

- indigestion – pain or burning sensation in the abdomen (heartburn), frequent burping, or stomach acid coming back up into the oesophagus (reflux)

- persistent nausea and/or vomiting (feeling or being sick) with no apparent cause

- abdominal (belly) pain

- feeling full after eating even a small amount

- swelling of the abdomen or feeling bloated

- unexplained tiredness, which may be due to low red blood cells (called anaemia)

- vomit that has blood in it

- black or bloody stools (poo)

What are the risk factors for stomach cancer?

The exact causes of stomach cancers are not known. Research shows that the factors listed below may increase your risk. Having one or more of these risk factors does not mean you will develop cancer. Many people have these risk factors and do not develop stomach cancer.

Factors known to increase the risk of stomach cancer

- older age (being over 60)

- infection with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

- smoking tobacco

- low red blood cell levels related to pernicious anaemia

- a family history of stomach cancer

- having an inherited genetic condition like familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Lynch syndrome, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), or gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS)

- chronic inflammation of the stomach (chronic gastritis)

- carrying extra body weight (overweight or obese)

- drinking alcohol

- eating salt-preserved foods (e.g. ham)

- having a subtotal gastrectomy for a non-cancerous condition.

What is oesophageal cancer?

Oesophageal cancer begins when abnormal cells develop in the innermost layer (mucosa) of the oesophagus. A tumour can start anywhere along the oesophagus. There are 2 main types:

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma – This often starts near the gastro-oesophageal junction and is linked with Barrett’s oesophagus. Adenocarcinomas are the most common form of oesophageal cancer in Australia.

Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma – This starts in the thin, flat cells of the mucosa, which are called squamous cells. It often begins in the middle and upper part of the oesophagus. In Australia, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma is less common than oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

If it is not found and treated early, oesophageal cancer can spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body, most commonly the liver and lungs. It can also grow through the oesophageal wall and into nearby organs.

Some cancers start at the point where the stomach meets the oesophagus (called the gastro-oesophageal junction). Depending on the location of the gastro-oesophageal cancer, it may be treated similarly to stomach cancer or oesophageal cancer.

How common is oesophageal cancer?

In Australia, about 1740 people are diagnosed with oesophageal cancer each year. Men are much more likely than women to be diagnosed with this cancer.

What are the symptoms of oesophageal cancer?

Oesophageal cancer may not cause symptoms in the early stages. Common symptoms are listed below.

These symptoms can also be caused by many other conditions and do not necessarily mean that you have cancer. Speak with your general practitioner (GP) if you are concerned.

Common symptoms of oesophageal cancer

- difficulty swallowing

- new heartburn or reflux

- reflux that doesn’t go away

- food or fluids “catching” in the throat, or episodes of bringing food back up (regurgitation), or vomiting when swallowing

- pain when swallowing

- unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite

- feeling uncomfortable in the upper abdomen, especially when eating

- unexplained tiredness that won’t go away

- vomit that has blood in it

- black or bloody stools (poo)

What are the risk factors for oesophageal cancer?

The exact causes of oesophageal cancers are not known. Research shows that the factors listed below may increase your risk. Having one or more of these risk factors does not mean you will develop cancer. Many people have these risk factors and do not develop oesophageal cancer.

Factors known to increase risk of oesophageal cancer

Adenocarcinoma

- carrying extra body weight (overweight or obese)

- medical conditions, including gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and Barrett’s

oesophagus - smoking tobacco

- older age (being over 60)

Squamous cell carcinoma

- drinking alcohol

- smoking tobacco

- older age (being over 60)

- damage to the oesophagus from hot or corrosive liquids such as acid

GORD and Barrett’s oesophagus

Reflux is when stomach acid rises back into the oesophagus. Some people with reflux are diagnosed with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Over a period of time, stomach acid can damage the lining of the oesophagus and cause inflammation or ulcers (oesophagitis).

This condition is called Barrett’s oesophagus. It only develops in about 1 in 10 people with GORD.

In some people, Barrett’s oesophagus can lead to the development of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, but this is rare.

If you have Barrett’s oesophagus, your doctor may recommend you have regular endoscopies.

In this procedure, a thin, flexible tube with a light and camera on the end is inserted down your throat so the doctor can look for early changes to the cells that may cause cancer.

Other types of cancer in the stomach and oesophagus

Other types of tumours can start in the stomach and oesophagus. These include small cell carcinomas, lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumours and gastrointestinal stromal tumours. These types of cancer aren’t discussed on these pages and treatment may be different.

Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information

Which health professionals will I see?

Your GP will assess your symptoms and arrange the first tests. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist such as a gastroenterologist or an upper gastrointestinal surgeon for an endoscopy and further tests.

If you are diagnosed with stomach or oesophageal cancer, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care. The most common health professionals that you may see are

listed below.

Health professionals you may see

Gastroenterologist – diagnoses and treats digestive system disorders; may perform endoscopies and insert feeding tubes

Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeon – diagnoses and performs surgery for diseases of the upper digestive system (such as cancer); performs endoscopies and inserts feeding tubes

Medical Oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Radiation Oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiation Therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy

Cancer Care Coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with MDT members and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to your diet during treatment and recovery

Physiotherapist, Exercise Physiologist – help with restoring movement and mobility, and

preventing further injury

Speech Pathologist – helps with communication and swallowing after treatment

Social Worker – links you to support services and helps with emotional and practical issues

Counsellor, Psychologist – use evidence-based strategies to help you manage emotional conditions, usually in the long term

Palliative Care Team – work closely with your GP and cancer specialists to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life

How are stomach and oesophageal cancers diagnosed?

If your GP suspects that you have stomach or oesophageal cancer, they will examine you, arrange initial tests and refer you to a specialist.

The main tests are endoscopy and biopsy (the removal of a tissue sample). You may have other tests to check your overall health and see if the cancer has spread. Your specialist will review all the test results to work out the overall stage and prognosis of the cancer.

Endoscopy and biopsy

An endoscopy (also called a gastroscopy, oesophagoscopy or upper endoscopy) is a procedure that allows your doctor to look at the lining of your gastrointestinal tract. It is usually done as day surgery.

Having an endoscopy – You will be told not to eat or drink (to fast) for 6 hours before an endoscopy. In some cases, you can drink clear fluids until 2 hours before the procedure. Your doctor will let you know about this. To make the procedure more comfortable, you’re likely to be offered sedation to make you feel sleepy. A general anaesthetic is only needed for a small number of cases. Once the sedative has taken effect, a long, flexible tube with a light and small camera on the end (endoscope) will be passed into your mouth, down your throat and oesophagus, and into your stomach and small bowel.

Taking a biopsy – If the doctor sees any areas that look like cancer, they may remove a small amount of tissue from the stomach or oesophageal lining. This is called a biopsy. A specialist doctor called a pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. Biopsy results are usually available in 2–3 working days.

An endoscopy takes about 10 minutes. You may feel drowsy or weak after the procedure, so will need to have someone take you home. You may have a sore throat and feel a little bloated for some time afterwards.

Endoscopies have some risks, such as bleeding or getting a small tear or hole in the stomach or oesophagus (perforation). These complications are very uncommon. Your doctor should explain all the risks before asking you to agree (consent) to the procedure.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

You may have an EUS at the same time as a standard endoscopy. The doctor will use an endoscope with an ultrasound probe on the tip or with a built-in ultrasound device. The probe releases soundwaves that echo when they bounce off anything solid, such as an organ or

tumour. This test helps work out whether the cancer has spread into the oesophageal or stomach wall, nearby tissues or lymph nodes. During the EUS, your doctor may use the ultrasound to guide a needle into the area they want to look at and take tissue samples.

Further tests

If the biopsy shows you have stomach or oesophageal cancer, you will have some of the following tests to work out whether the cancer has spread to other areas of your body. This is called staging. Some of the tests may be repeated during or after treatment to check your health and see how well the treatment is work.

Blood tests

You may have blood tests to assess your general health, check for a low red blood cell count (anaemia), and see how well your liver and kidneys are working.

CT scan

A computerised tomography (CT) scan uses x-ray beams to create detailed, cross-sectional pictures of the inside of your body. It helps show the size of the cancer and if it has spread. You may have a CT scan of your chest and abdomen (belly).

Before a CT scan, you may be injected with dye and/or asked to drink a liquid dye. If you have an injection, a small, plastic tube (called a cannula) is inserted into a vein in your arm. This dye (called contrast) helps ensure that anything unusual in your body, like a tumour, can be seen more clearly. The dye may cause a warm feeling throughout your body, and leave a metallic taste in your mouth for a few minutes. Rarely, more serious reactions may occur.

The CT scan machine is large and round like a doughnut. You will need to lie still on a table while the scanner moves around you. It usually takes 10–30 minutes to prepare the CT scan machine and insert the cannula, but the scan itself takes only a few minutes and is painless.

PET–CT scan

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan combined with a CT scan is a specialised imaging test. The CT scan helps pinpoint the location of any abnormalities found by the PET scan. A PET–CT scan can be used in staging stomach and oesophageal cancer, particularly in preparation for surgery.

To prepare for a PET–CT scan, you will be asked not to eat or drink (to fast) in the lead-up to having the scan. Your treatment team will talk to you about this. Before the scan, you will be injected with a glucose solution containing a small amount of short-acting radioactive

material. Cancer cells usually show up brighter on the scan because they take up more glucose solution than normal cells do.

You will be asked to sit or lie quietly for 30–90 minutes as the glucose spreads through your body, then you will be scanned. The scan itself takes about 30 minutes. Let your doctor know if you have claustrophobia, as you need to be in a confined space for the scan.

Laparoscopy

This procedure is a type of keyhole surgery. It allows your doctor to look for signs that the cancer has spread to the outer layer of the stomach and the lining of the wall of the abdomen (called the peritoneum). Your doctor will explain the risks before asking you to agree to have the procedure.

A laparoscopy is usually done as day surgery under general anaesthetic. The doctor will make small cuts in your abdomen and pump in gas to inflate your abdomen. A tube with a light and camera attached (a laparoscope) will then be inserted into your body. The camera projects

images onto a monitor so the doctor can see cancers that are too small to be seen on CT or PET–CT scans. The doctor may take more tissue samples for biopsy. Sometimes, the surgeon will wash some salt water (saline) into the peritoneal cavity and then remove the fluid for further testing for cancer cells. This is called a peritoneal lavage.

After the procedure you may feel bloated and the gas in your abdomen may cause pain in your shoulder.

Endoscopic resection

If you are diagnosed with very early cancer in the stomach or oesophagus, you may have an endoscopic resection, which aims to remove the whole tumour during the endoscopy.

For some people, the resection not only helps in diagnosis and staging, but also may treat the cancer and further treatment is not needed. An endoscopic resection is often done as a day procedure but in some cases, you may stay in hospital overnight for observation.

Molecular testing

If you are diagnosed with advanced cancer in the stomach, oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction, your doctor may test the biopsy sample to see whether one of the available targeted therapy or immunotherapy drugs would be suitable for you.

The test will look for particular features within the cancer, such as changes to the HER2 protein, a special protein known as PD-L1, or a marker called microsatellite instability (MSI). This type of testing is known as molecular testing.

Staging

The tests described above help show whether you have stomach or oesophageal cancer and whether it has spread. Working out how far the cancer has spread is called staging. It helps your doctors recommend the best treatment for you.

The TNM staging system is the method most often used to stage stomach and oesophageal cancers. TNM stands for “tumour, node, metastasis”. The specialist gives numbers to the size of the tumour (T1–4), whether or not lymph nodes are affected (N0–N3), and whether the cancer has spread or metastasised (M0 or M1). The lower the numbers, the less advanced the cancer.

The TNM scores are combined to work out the overall stage of the cancer, from stage 1 to stage 4. Ask your doctor to explain what the stage of the cancer means for you. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Stages of stomach and oesophageal cancers

Stage 1 (early or limited cancer) – tumours are found only in the stomach or oesophageal wall lining

Stages 2–3 (locally advanced cancer) – tumours have spread deeper into the layers of the stomach or oesophageal wall and to nearby lymph nodes

Stage 4 (metastatic or advanced cancer) – tumours have spread beyond the stomach or oesophageal wall to nearby lymph nodes or parts of the body, or to distant lymph nodes and parts of the body

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease. Instead, your doctor can give you an idea about the general prognosis for people with the same type and stage of cancer.

To work out your prognosis and advise you on treatment options, your doctor will consider your test results; the type of cancer; the size of the cancer and how far it has grown into other tissue; whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes; how it might respond to treatment; and your age, level of fitness and medical history.

Generally, the earlier stomach or oesophageal cancer is diagnosed, the better the outcome of treatment. If cancer is found after it has spread, it may not respond as well to treatment.

Treatment for stomach cancer

Your health care team will recommend treatment based on where the cancer is in the stomach, and whether it has spread (the stage).

Treatment will also depend on your age, medical history, nutritional needs and general health.

Surgery is often part of the treatment for stomach cancer that has not spread. If the cancer has spread, treatment may also include chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy or radiation therapy.

What to do before treatment starts

Improve diet and nutrition – People with stomach cancer often lose a lot of weight and can become malnourished. Your doctor will usually refer you to a dietitian for advice on how to slow down the weight loss.

Stop smoking – If you smoke or vape, aim to quit before starting treatment. People who keep smoking may not respond as well to treatment. See your doctor or call the Quitline on 13 7848 for advice and support.

Begin or continue an exercise program – Exercise can help build your strength for recovery. Talk to

your doctor, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist about an exercise plan.

Avoid alcohol – Talk to your doctor about your alcohol use. Alcohol can affect how the body works and increase the risk of complications after surgery (including bleeding and infections), and of the cancer returning.

Talk to someone – You may find it useful to talk to a counsellor or psychologist about how you are feeling. This can help you deal with any anxiety about diagnosis and treatment. Or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to find out about support services.

Endoscopic resection for stomach cancer

Very early-stage tumours in the inner layers of the stomach (mucosa) may be removed with an endoscope through endoscopic resection. For some people, this may be the only treatment they need. You usually stay in hospital overnight for endoscopic resection. Preparation and recovery are similar to an endoscopy, but there is a slightly higher risk of bleeding or a small tear in the stomach (perforation).

Surgery for stomach cancer

Surgery aims to remove all of the stomach cancer while keeping as much of the stomach as possible. The surgeon will also remove some healthy tissue around the cancer to reduce the risk of the cancer returning. Different types of surgery can be used depending on where the cancer is in the stomach. Your surgeon will talk to you about the best way to perform surgery for you.

How the surgery is done

The surgery will be done under a general anaesthetic. There are 2 ways to perform surgery for stomach cancer:

- Open surgery (laparotomy) – The surgeon makes a long cut in the upper part of the abdomen from the breastbone to the bellybutton.

- Keyhole surgery – The surgeon makes some small cuts in the abdomen, then inserts a thin instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) into one of the cuts. The surgeon puts tools into the other cuts and performs the surgery using the images from the camera for guidance. Also called laparoscopic or minimally invasive surgery.

Types of stomach surgery

Subtotal or partial gastrectomy – Only part of the stomach is removed when the cancer is in the lower part of the stomach. Nearby fatty tissue (omentum) and lymph nodes are also removed. The upper stomach and oesophagus are usually left in place.

Total gastrectomy – The whole stomach is removed when the cancer is in the upper or middle part of the stomach. Nearby fatty tissue (omentum), lymph nodes and parts of nearby organs, if necessary, are also removed. The surgeon rejoins the oesophagus to the small bowel.

Lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection) – Lymph nodes are removed from around your stomach to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back and to help in the staging of the cancer.

Risks of stomach surgery

Your surgeon will talk to you about the risks of surgery. These may include infection, bleeding, or leaking from the joins between the small bowel and either the oesophagus or stomach. You will be monitored for side effects.

What to expect after surgery

This is a general overview of what to expect. The process varies from hospital to hospital, and everyone will respond to surgery differently. Some hospitals have special programs – called Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) – to support you in the recovery period.

Recovery time

- When you wake up after the operation, you will be in a recovery room near the operating theatre or in the intensive care unit.

- Most people will need a high level of care. You can expect to spend time in the high dependency unit or intensive care unit before moving to a standard ward.

- How long you stay in hospital will depend on the type of stomach surgery you had, your age and your general health.

- You will probably be in hospital for 3–10 days, but it can take 3–6 months to fully recover from a gastrectomy.

- Talk to your treatment team if you have any concerns about caring for yourself at home. If you think you will need home nursing care, ask about services in your area.

Help with your recovery

- You will have some pain and discomfort for several days after surgery, which will be managed with pain medicines. This may be given as tablets or injections, or you may have patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), which delivers a dose of pain medicine through a drip when you press a button.

- Let your doctor or nurse know if you’re in pain so they can adjust your medicines to make you as comfortable as possible. Do not wait until the pain is severe.

- You may have a dressing over the wound. The doctor or nurse will talk to you about how to keep the wound clean and free from infection when you go home.

- You will have several tubes in your body, which will be removed as you recover. You may have a drip in your arm to give you pain relief and to replace your body’s fluids until you are able to drink and eat again. You may have a tube from your bladder (catheter) to collect urine in a bag. You may also have a feeding tube.

Eating and drinking

- Your treatment team will talk to you about the impact of surgery on how you eat and drink in the short term and long term.

- When you can eat again, you will usually start with milk, soup, ice-cream and yoghurt. Then you will move to pureed foods, then to soft foods, and eventually back to normal, solid food. This process happens over several weeks.

- Eating 6–8 small meals or snacks throughout the day may make it easier to manage than a few large meals. Ask the hospital dietitian for advice about meal and snack ideas and whether you need to take any nutritional supplements.

- A feeding tube may be put into the small bowel through a cut in the abdomen. Special feeding formula is given through this tube while the join between the oesophagus and small bowel heals.

Activity and exercise

- Your treatment team will probably encourage you to walk the day after surgery. Gentle exercise has been shown to help people manage some treatment side effects, speed up a return to usual activities and improve quality of life. Ask your doctor or nurse for guidance on the right activity levels for you and if there are any suitable exercise programs available in your area.

- You will have to wear compression stockings for a couple of weeks to help the blood in your legs circulate and reduce the risk of developing blood clots.

- Check whether you need to avoid driving and heavy lifting for a few weeks after the surgery.

- A physiotherapist will teach you breathing or coughing exercises to help keep your lungs clear and reduce the risk of a chest infection.

Having a feeding tube

Some people with stomach cancer will have a feeding tube before and/or during treatment to help them maintain their weight and build up their strength.

The feeding tube may also be needed after surgery until it is possible to eat and drink normally. You can be given specially prepared feeding formula through this tube.

If you go home with the feeding tube in place, a dietitian will let you know the type and amount of feeding formula you need to take.

How feeding tubes can help

Many people find that having a feeding tube is a more comfortable way to stay well-nourished if the cancer is making eating and drinking difficult.

Medicines can also be given through some feeding tubes, although you cannot do this with very small feeding tubes because they may become blocked.

If you are unsure about putting certain medicines through the feeding tube, talk to your doctor,

pharmacist or dietitian.

How feeding tubes are placed

A feeding tube can be placed into your small bowel or stomach either through a nostril (nasojejunal or nasogastric tube) or with an operation that places a tube through the skin of your abdomen (gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube).

How to care for a feeding tube

Your treatment team will show you how to care for the tube to keep it clean and prevent leaking and blockages, and when to replace the tube.

You can avoid getting infections by washing your hands before using the tube, and keeping the tube and your skin dry.

Your doctor will remove the feeding tube when it is no longer required.

How to cope with a feeding tube

Having a feeding tube is a major change and it’s common to have a lot of questions. Getting used to having a feeding tube takes time.

For information, talk to a dietitian or nurse. A counsellor or psychologist can provide emotional support and coping strategies.

Chemotherapy for stomach cancer

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. For stomach cancer, it is used:

- before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) – to shrink large tumours and destroy any cancer cells that may have spread

- after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) – to reduce the chance of the cancer coming back

- as palliative treatment – to help control the cancer and improve quality of life; this can sometimes prolong overall survival.

Chemotherapy drugs are usually given as a liquid through a drip inserted into a vein (intravenous infusion). It may also be given through a tube that is implanted and stays in your vein throughout treatment. This is called a central venous access device (CVAD) and there are

different types (e.g. a port-a-cath). Sometimes, chemotherapy is given as tablets you swallow. You will usually receive treatment as an outpatient (when you visit hospital for treatment but are not admitted).

Most people have a combination of chemotherapy drugs over several treatment sessions, with rest periods of 2–3 weeks in between. Together, the session and rest period are called a cycle. Your doctor will talk to you about how long your treatment will last.

Side effects of chemotherapy – These may include feeling sick (nausea), vomiting, appetite changes and difficulty swallowing, sore mouth or mouth ulcers, skin and nail changes, numbness in the hands or feet, ringing in the ears or hearing loss, constipation or diarrhoea, and hair loss or thinning. You may also be more likely to catch infections. If you feel unwell or have a temperature of 38°C or higher, seek urgent medical attention.

Targeted therapy for stomach cancer

Targeted therapy is a type of drug treatment that attacks specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading.

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein that causes cancer cells to grow. If you have HER2-positive advanced stomach or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer, you may be given a targeted therapy drug called trastuzumab. This drug destroys the HER2-positive cancer cells or slows their growth. Trastuzumab is given with chemotherapy every 2–3 weeks through a drip into a vein.

Another targeted therapy drug called ramucirumab aims to reduce the blood supply to a tumour to slow or stop its growth. It has been approved to treat advanced stomach or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer that has not responded to chemotherapy, but is not subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

Side effects of targeted therapy – Ask your doctor what side effects to expect. Possible side effects of trastuzumab include fever and nausea. In some people, trastuzumab can affect the way the heart works. Possible side effects of ramucirumab include stomach cramps, diarrhoea and high blood pressure. Tell your doctor about any side effects immediately.

Immunotherapy for stomach cancer

There have been some advances in treating advanced stomach cancer with immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors. These use the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

A checkpoint inhibitor drug called nivolumab may be used with chemotherapy for some people with advanced stomach cancer that has high levels of the protein PD-L1. Nivolumab may also be used when chemotherapy hasn’t worked or when the tumour has a high level of the marker MSI.

Side effects of immunotherapy – Not everyone will experience the same effects, but they may include redness, swelling (inflammation) or pain in any of the organs of the body, leading to common side effects such as fatigue, skin rash, diarrhoea and cough. The inflammation can lead to more serious side effects in some people, but this will be monitored closely and managed quickly. Let your treatment team know immediately if you develop any side effects.

Radiation therapy for stomach cancer

Radiation therapy, also known as radiotherapy, this treatment uses a controlled dose of radiation, such as focused x-ray beams, to kill or damage cancer cells. Radiation therapy for stomach cancer is commonly used to control bleeding.

Radiation therapy is usually given as a short course (1–14 days). Occasionally, a longer course of radiation therapy (5–6 weeks) will be given, either before or after surgery, or if surgery is not possible.

Each treatment takes about 15 minutes and is not painful. You will lie on a table under a machine that delivers radiation to the affected parts of your body. Your doctor will let you know your treatment schedule. Possible side effects include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and loss of appetite.

Palliative treatment

Palliative treatment helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease. It is best thought of as part of supportive care. Many people think that palliative treatment is for people at the end of life, but it may help at any stage of advanced stomach cancer. It is about helping you live for as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

The treatment you are offered will be tailored to your individual needs, and may include surgery, stenting, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or other medicines. These treatments can help manage symptoms such as pain, bleeding, difficulty swallowing and nausea. They can also slow the spread of the cancer.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals help meet your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Treatment for oesophageal cancer

The most important factor in planning treatment for oesophageal cancer is the stage of the disease.

Your treatment will also depend on your age, nutritional needs, medical history and general health.

Treatment options for oesophageal cancer include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, either alone or in combination. Treatment will be tailored to your specific situation.

Your doctor will tell you how to prepare for surgery and other treatments. Preparation may include general health checks such as blood tests and scans to check how well your heart is working (called an echocardiogram).

What to do before treatment starts

Improve diet and nutrition – People with oesophageal cancer often lose a lot of weight and can become malnourished. Your doctor will usually refer you to a dietitian for advice on how to slow down the weight loss.

Stop smoking – If you smoke or vape, aim to quit before starting treatment. People who keep smoking may not respond as well to treatment. See your doctor or call the Quitline on 13 7848 for advice and support.

Begin or continue an exercise program – Exercise can help build your strength for recovery. Talk to

your doctor, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist about an exercise plan.

Avoid alcohol – Talk to your doctor about your alcohol use. Alcohol can affect how the body works and increase the risk of complications after surgery (including bleeding and infections), and of the cancer returning.

Talk to someone – You may find it useful to talk to a counsellor or psychologist about how you are feeling. This can help you deal with any anxiety about diagnosis and treatment. Or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to find out about support services.

Endoscopic resection for oesophageal cancer

Very early-stage tumours in the lining of the oesophageal wall (mucosa) may be removed with an endoscope through endoscopic resection. For some people, an endoscopic resection may be the only treatment they need.

An endoscopic resection is often done as a day procedure but occasionally needs an overnight stay in hospital. Preparation and recovery are similar to an endoscopy, but there is a slightly higher risk of bleeding or getting a small tear or hole in the oesophagus (perforation).

Surgery for oesophageal cancer

When oesophageal cancer has not spread to other organs, surgery is often recommended as long as you are well enough.

Surgery aims to remove all of the cancer while keeping as much healthy tissue as possible. The surgeon will also remove some healthy tissue around the cancer to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back in the future.

Depending on where the tumour is growing and how advanced the cancer is, you may have an endoscopic resection or an oesophagectomy.

How the surgery is done

To remove the cancer, the surgery can be done in two ways:

- Open surgery – The surgeon makes a large cut in the chest and the abdomen, and, sometimes, a small cut in the neck.

- Keyhole surgery – The surgeon makes some small cuts in the abdomen and/or between the ribs, then inserts a thin instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) into one of the cuts to see inside the body. Sometimes a small cut is made at the base of the neck on the left side. This may be used to join the oesophagus and stomach back together.

Your surgeon will talk to you about the best type of surgery for you.

Surgery for oesophageal cancer is complex. Surgeons who regularly perform this type of surgery have better outcomes, which means that if you live far from a specialist centre, you will have to travel to have surgery. You may be eligible for help with travel costs. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

Oesophagectomy (surgical resection)

Surgery to remove part or all of the oesophagus is called an oesophagectomy. Nearby affected lymph nodes are also removed. It is common to have chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy before surgery, as this approach has been shown to have better results.

Depending on where in the oesophagus the cancer is, the surgeon may also remove part of the upper stomach. This is the preferred option for cancer that has spread deeper into the wall of the oesophagus or to nearby lymph nodes.

Once the parts with cancer have been removed, the stomach is pulled up and rejoined to the healthy part of the oesophagus. This will allow you to swallow and, in time, eat relatively normally. If the oesophagus cannot be rejoined to the stomach, the oesophagus will be connected to the small bowel, or a part of the bowel will be used to replace the part of the oesophagus that was removed. These procedures will help you swallow.

Risks of oesophageal surgery

As with any major surgery, oesophageal surgery has risks. These may include infection, bleeding, blood clots, damage to nearby organs, leaking from the joins between the oesophagus and stomach or small bowel, pneumonia and voice changes. Some people may have an irregular heartbeat, but this usually settles within a few days.

Surgical scars can narrow the oesophagus (called oesophageal stricture) and make it difficult to swallow. If the oesophagus becomes too narrow, your doctor may need to stretch the walls of the oesophagus (dilatation).

Your surgeon will discuss these risks with you before surgery, and you will be carefully monitored for any side effects.

What to expect after oesophageal surgery

Recovery after oesophageal surgery is similar to stomach surgery, but there are some differences.

Recovery time – You will probably be in hospital for 7–10 days, but you may stay longer if you have any complications. It is likely to take 6–12 months to feel completely better after an oesophagectomy.

Eating and drinking – You will not be able to eat or drink immediately after surgery. A temporary feeding tube is often inserted at the time of the surgery. Once you begin eating, you will usually start with fluids such as soup, and then move on to pureed foods, then soft foods, and eventually normal, solid foods. It is best to eat 5–6 small meals throughout the day as you may feel full quickly.

Breathing problems – Controlling pain will help avoid problems with breathing that can lead to pneumonia. A physiotherapist can teach you exercises to help keep your lungs clear. You may also be shown how to use an incentive spirometer, a device to help your lungs expand and prevent a chest infection.

Drips and drains – You may have a feeding tube to get the nutrition you need, and another tube (nasogastric or NG tube) to drain fluids from the stomach. The NG tube will be removed before you leave hospital, but a feeding tube is likely to stay in and be removed after you have gone home.

Having a feeding tube

Some people with oesophageal cancer will have a feeding tube before and/or during treatment to help them maintain their weight and build up their strength.

The feeding tube may also be needed after surgery until it is possible to eat and drink normally. You can be given specially prepared feeding formula through this tube.

If you go home with the feeding tube in place, a dietitian will let you know the type and amount of feeding formula you need to take.

How feeding tubes can help

Many people find that having a feeding tube is a more comfortable way to stay well-nourished if the cancer is making eating and drinking difficult.

Medicines can also be given through some feeding tubes, although you cannot do this with very small feeding tubes because they may become blocked.

If you are unsure about putting certain medicines through the feeding tube, talk to your doctor,

pharmacist or dietitian.

How feeding tubes are placed

A feeding tube can be placed into your small bowel or stomach either through a nostril (nasojejunal or nasogastric tube) or with an operation that places a tube through the skin of your abdomen (gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube).

How to care for a feeding tube

Your treatment team will show you how to care for the tube to keep it clean and prevent leaking and blockages, and when to replace the tube.

You can avoid getting infections by washing your hands before using the tube, and keeping the tube and your skin dry.

Your doctor will remove the feeding tube when it is no longer required.

How to cope with a feeding tube

Having a feeding tube is a major change and it’s common to have a lot of questions. Getting used to having a feeding tube takes time.

For information, talk to a dietitian or nurse. A counsellor or psychologist can provide emotional support and coping strategies.

Radiation therapy for oesophageal cancer

Radiation therapy, also known as radiotherapy, uses a controlled dose of radiation, such as focused x-ray beams, to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is targeted at the cancer, and treatment is carefully planned to do as little harm as possible to healthy body tissue near the cancer.

Radiation therapy is the main treatment for oesophageal cancer that has not spread to other parts of the body and cannot be removed with surgery. It may be given alone or combined with chemotherapy (called chemoradiation). Chemoradiation is often used 1–3 months before surgery to shrink large tumours and destroy any cancer cells that may have spread.

Before starting treatment, you will have a planning session that will include a CT scan. Some small permanent or temporary tattoos may be made on your skin so that the same area is targeted during each treatment session.

Side effects of radiation therapy – The lining of the oesophagus can become sore and inflamed (oesophagitis). This can make swallowing and eating difficult. In rare cases, you may need a temporary feeding tube to help you get enough nutrition. Other possible side effects include fatigue, skin redness, loss of appetite and weight loss. Most side effects improve within about 4 weeks of treatment finishing.

Very rarely, long-term side effects can develop. The oesophagus can develop scar tissue and get narrower (called oesophageal stricture). Stretching the walls of the oesophagus (dilatation) can make it easier to swallow food and drink. Radiation therapy can also cause irritation and swelling (inflammation) in the lungs, making you short of breath.

Chemotherapy for oesophageal cancer

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells, while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells.

Chemotherapy for oesophageal cancer may be given alone or it may be combined with radiation therapy (called chemoradiation).

For oesophageal cancer, chemotherapy may be used:

- before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) – to shrink a large tumour and destroy any cancer cells that may have spread

- after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) – to reduce the chance of the disease coming back

- on its own (palliative treatment) – for people unable to have surgery or where cancer has spread to different parts of the body.

Chemotherapy drugs are usually given as a liquid through a drip inserted into a vein (intravenous infusion). It may also be given through a central venous access device (CVAD) or as tablets you swallow. You will usually receive treatment as an outpatient. Most people have a combination of chemotherapy drugs over several treatment sessions. There may be a rest period of a few weeks between each treatment session.

Side effects of chemotherapy – Your treatment team can help you prevent or manage any side effects. Common side effects may include nausea and/or vomiting, appetite changes and difficulty swallowing, sore mouth or mouth ulcers, skin and nail changes, numbness or tingling in the hands or feet, ringing in the ears or hearing loss, changed bowel habits (e.g. constipation, diarrhoea), and hair loss or thinning.

Chemotherapy affects your immune system, so you may also be more likely to catch infections. If you feel unwell or have a temperature of 38°C or higher, seek urgent medical attention.

Chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer

Treatment with radiation therapy and chemotherapy is called chemoradiation. The chemotherapy drugs make the cancer cells more sensitive to radiation therapy.

Oesophageal cancer may be treated with chemoradiation before surgery to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove. Chemoradiation may also be used as the main treatment when the tumour can’t be safely removed with surgery, or if the doctor thinks the risk with surgery is too high.

If you have chemoradiation, you will usually have chemotherapy a few hours before some radiation therapy appointments. Your doctor will talk to you about the treatment schedule and how to manage any side effects.

You will usually have treatment as an outpatient (when you are not admitted to hospital) once a day, Monday to Friday, for 4–6 weeks. If radiation therapy is used palliatively, you may have a short course of 1–15 sessions. Each treatment takes about 10 minutes and is not painful. You will lie on a table under a machine that delivers radiation to the affected parts of your body. Your doctor will let you know your treatment schedule.

Immunotherapy for oesophageal cancer

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Nivolumab is a type of immunotherapy drug called a checkpoint inhibitor. It may be given to people after surgery or to some people with advanced oesophageal cancer.

This area of cancer treatment is changing rapidly. Talk to your doctor about whether immunotherapy is an option for you.

Side effects of immunotherapy – The side effects of immunotherapy can vary from person to person. Immunotherapy can cause redness, swelling or pain (inflammation) in any of the organs of the body, leading to common side effects such as fatigue, skin rash, diarrhoea and cough. The inflammation can lead to more serious side effects in some people, but this will be monitored closely and any issues will be managed quickly.

Let your treatment team know immediately if you develop any side effects or have concerns.

Palliative treatment

Palliative treatment helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease. It is best thought of as supportive care. Many people think that palliative care is for people at the end of life, but it can help at any stage of advanced oesophageal cancer.

Treatments will be tailored to your individual needs. For example, radiation therapy can help to relieve pain and make swallowing easier by helping to shrink a tumour that is blocking the oesophagus. Palliative treatments can also slow the spread of the cancer.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals helps meet your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs. The team can also provide support to families and carers.

Having a stent

People with advanced oesophageal cancer who are having trouble swallowing and do not have any other treatment options may have a flexible tube (called a stent) inserted into the oesophagus.

The stent expands the oesophagus to allow fluid and soft food to pass into the stomach more easily. It also prevents food and saliva going into the lungs and causing infection. The stent does not treat the cancer but will allow you to eat and drink more normally.

Stents can cause indigestion (heartburn) and discomfort. Occasionally, the stents will move down the oesophagus into the stomach and may need to be removed.

Managing side effects

Stomach and oesophageal cancers and their treatment can cause side effects.

Some of these side effects are permanent and may change what you can eat, and how you digest foods and absorb essential nutrients. This section explains common side effects and how to manage them.

Eating after treatment

During and after treatment, you need to eat and drink enough to get the nutrition you need, maintain your weight and avoid dehydration. Ask your doctor for a referral to a dietitian with experience in cancer care, who can give you more information. If you are eating less than usual, it is often recommended that you have high energy and high protein foods and relax healthy eating guidelines. You may need a feeding tube during or after treatment if you are unable to eat and drink enough to meet your nutritional needs.

After treatment, you may find that some foods are uncomfortable to eat and cause digestive problems. You will need to try different foods and change your eating habits, such as eating smaller meals more often throughout the day.

You may find it hard to accept the differences in how and what you can eat. It’s natural to feel self-conscious or worry about eating in public or with friends. It may help to let your family and friends know how you feel, or to speak with a counsellor or someone who has been through a similar experience. They may be able to give you advice to help you adjust. It may take time and support to adapt to your new way of eating.

Poor appetite and weight loss

After surgery, your stomach will be smaller (or completely removed) and you will feel full more quickly after a meal. You may not feel like eating or you may have lost your sense of taste. You may also have trouble swallowing or pain. It is important to maintain your weight to avoid malnutrition. Even a small drop in weight (e.g. 3–4 kg), particularly over a short period of time, can slow down your recovery. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can cause nausea, irritation to the oesophagus or a sore mouth. These side effects may make eating uncomfortable.

How to prevent unplanned weight loss

- Have a snack or small meal every 2–3 hours if you have lost your appetite and don’t feel hungry.

- Keep a variety of snacks on hand (e.g. in your bag or car).

- Eat when you feel hungry or crave certain foods. Eat slowly and stop and rest when you are full.

- Avoid filling up on liquids at mealtimes, unless it’s a hearty soup, so you have room for nourishing food.

- Try eating different foods to see if your taste and tolerance for some foods have changed.

- Try to drink fluids that add energy (kilojoules), such as milk, milkshakes, smoothies or nutritional supplement drinks recommended by your dietitian.

- Prevent dehydration by drinking fluids between meals (30–60 minutes before or after meals).

- Ask your dietitian how you can increase your energy and protein intake.

- It may be helpful to use a food diary to keep a record of how you react to certain foods. Ask your dietitian about this.

Swallowing difficulties

You may have difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) before, during or after treatment. This may be caused by the cancer itself or by swelling in the oesophagus after surgery. Signs include: taking longer to chew and swallow; food getting caught in your mouth or throat; or bringing up food or vomiting.

Some people find that food and fluid go into the windpipe instead of the food pipe. This is called aspiration and it can lead to chest infections like pneumonia. Talk to your doctor about these symptoms.

How to eat when it is hard to swallow

- Make food softer by chopping, mashing, slow-cooking, mincing or pureeing food.

- Between meals, snack on soft foods that are higher in energy and protein (e.g. avocado, yoghurt, ice-cream, custard, diced tinned fruit) and drink milkshakes.

- Chew carefully and slowly, sitting still and upright. Try to avoid talking while eating.

- Avoid dry foods such as bread, cakes, muffins and large chunks of meat. Add extra gravy or sauce to your meals.

- Wash food down with small sips of fluid.

- See a speech pathologist for help to manage these symptoms and suggestions on the types of foods to eat and ways to eat and drink safely.

- Talk to your doctor or dietitian if you are losing weight. They can help you find foods that provide enough nutrition and help you maintain your weight.

- Add special nutritional supplement drinks to your diet to help maintain your strength (e.g. Sustagen, Resource and Ensure).

Reflux and choking

Stomach acid rising into the oesophagus (reflux) is common after surgery for oesophageal cancer. This can cause heartburn, chest discomfort, or your stomach contents to flow up your oesophagus, particularly when lying flat or bending over. Medicines to reduce stomach acid may help.

After surgery or radiation therapy for oesophageal cancer, scar tissue may cause choking or swallowing problems while eating or drinking. See your doctor if this continues. After an oesophagectomy, the stomach can take longer to empty. You may feel full more quickly or be more likely to vomit or bring up food after eating.

How to reduce reflux and choking

- Avoid spicy foods, fatty foods, fizzy drinks, alcohol and citrus fruits if you find they trigger reflux.

- Take small sips of liquid to reduce coughing or choking.

- Chew foods well, eat slowly, and don’t talk while eating.

- To help food digest, sit up straight when eating and for at least 30 minutes after eating.

- Have your main meal earlier in the day and eat a small snack in the evening.

- After an oesophagectomy, sit up for 2–4 hours after eating. Eat your evening meal more than 4 hours before going to bed.

- Avoid positions where your head is below your stomach (e.g. when bending over too far), particularly after eating.

- Keep your chest higher than your stomach when sleeping by lifting the head of your bed with blocks about the thickness of a house brick. The whole bed should be tilted slightly.

- Ask your doctor how much physical activity you can do, as this can sometimes cause reflux.

Dumping syndrome

If surgery has changed the structure of your stomach, partially digested food can move into the small bowel too quickly. This can especially be a problem with sugary fluids, such as soft drinks, juices and cordial. You may have cramps, nausea, racing heart, sweating, bloating, diarrhoea or dizziness. Called dumping syndrome, this combination of symptoms usually occurs 15–30 minutes after eating.

Sometimes symptoms may occur 1–2 hours after a meal. Called late symptoms, they include weakness, light-headedness and sweating. These symptoms are usually worse after eating foods high in sugar.

How to manage dumping syndrome

- Have smaller meals throughout the day rather than 3 large meals.

- Chew your food well and eat slowly so your body can sense when it is full.

- Surgery may affect how you tolerate certain foods. Keep a record of foods that cause problems and talk to a dietitian for suggestions on what to eat to reduce the symptoms.

- Include sources of fibre with your meals (e.g. lentils, baked beans, fruits and vegetables with skins on, wholegrain breads).

- Eat meals high in protein (e.g. lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, milk, yoghurt, nuts, seeds, beans).

- Eat starchy foods (e.g. pasta, rice, potato).

- Avoid foods and drinks high in sugar (e.g. cordial, soft drinks, cakes and biscuits).

- Avoid drinking liquids with your meals; after drinking, wait at least 30 minutes before eating.

- Symptoms usually improve over time. If they don’t, ask your doctor for advice about medicines that may help.

Anaemia and osteoporosis

Surgery to remove the stomach will mean you will be unable to absorb some vitamins and minerals from food. This may lead to low levels of:

- Calcium – Over time, your bones may become weak and brittle, and break more easily (osteoporosis), which may cause pain.

- Vitamin B12 – Low B12 levels can cause a condition called pernicious anaemia. The most common symptom is tiredness. Other symptoms include pale skin, breathlessness, headaches, a racing heart and appetite loss. You may need regular vitamin B12 injections.

- Iron – Low iron levels can cause iron deficiency anaemia. You may need an iron infusion, in which iron is given as a liquid through a drip inserted into a vein. Iron taken by mouth can’t be absorbed easily.

Tips for managing anaemia

- Talk to your doctor about what type of anaemia you have and how to treat it.

- Eat foods rich in iron (e.g. meat, eggs and softened dark green leafy vegetables).

- To help your body absorb iron, eat foods high in vitamin C (e.g. red or orange fruits and vegetables).

- Avoid drinking tea and coffee with meals, as they can prevent your body absorbing iron.

- Rest when you need to.

- If you smoke, talk to your GP about quitting or call the Quitline on 13 7848. Smoking tobacco can increase the risk of developing anaemia.

- See your GP for regular blood tests to check on nutrient levels for at least 2 years after treatment.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had stomach or oesophageal cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. During these check-ups, you may have blood tests, imaging scans or an endoscopy if necessary. You will also be able to discuss how you’re feeling and any concerns you may have.

How often you will need to see your doctor will depend on the level of monitoring needed for the type and stage of the cancer you had. You should also see a dietitian for advice about good nutrition. Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people find that they think more about the cancer and may feel anxious. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people, stomach or oesophageal cancer does come back. This is known as a recurrence.

If the cancer returns, you may have further treatment, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy or surgery. Sometimes people have palliative treatment to ease symptoms. Treatment may be similar to what you had after your initial diagnosis, or you may be offered a different type of treatment if the cancer comes back in another part of your body.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible.

Cancer Council SA offers a free cancer counselling service, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.