What is adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)?

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a rare type of cancer that forms in glandular tissues most commonly in the head and neck, but it can also begin in other areas.

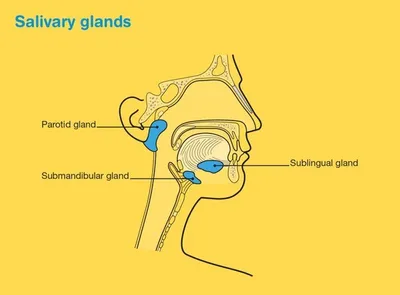

ACC often starts in the salivary glands in the neck, mouth or throat, which make saliva. Saliva keeps the mouth moist, helps you swallow food and protects the mouth against infections.

There are three pairs of major salivary glands and hundreds of minor salivary glands throughout the lining of the mouth and throat. The major salivary glands include:

- parotid glands – in front of the ears

- sublingual glands – under the tongue

- submandibular glands – under the jawbone.

Malignant (cancerous) tumours have the potential to spread to other parts of the body through the blood stream or lymph vessels and form another tumour at a new site. This new tumour is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

For more information on salivary gland cancer see our information on Head and Neck Cancers. Further information is also available from Head and Neck Cancer Australia and Rare Cancers Australia.

How common is ACC?

ACC is rare and may account for up to a quarter of salivary gland malignancies.

Around 330 Australians are diagnosed with a salivary gland cancer each year (this is 1.2 cases per 100,000 people).

Estimates of 0.3 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 people each year have been reported for ACC in other countries.

While ACC can develop at any age, it is more common in people 40 to 60 years old. Slightly more females are diagnosed than males.

What are the symptoms and the risk factors?

ACC generally develops slowly, sometimes over several years, and may not cause symptoms.

Most often it is diagnosed as a single tumour but may have spread to nearby lymph nodes by the time it is diagnosed in a small number of cases. Rarely, ACC can spread along nerves or metastasise to other parts of the body (usually the lungs, liver or bone) and cause problems. It can also be unpredictable, growing slowly for a period of time and then suddenly growing quickly. ACC may behave differently in different people.

If you do have symptoms it will depend on where in the body the tumour is located and its size. Symptoms may include:

- Salivary gland (produces saliva) – painless lump in the mouth, face or neck; numbness in the face; weakness in facial muscles (drooping in the face); problems swallowing or opening mouth

- Lacrimal gland (produces tears) – bulging eye; changes in vision

- Larynx (voice box) and trachea (windpipe) – hoarseness; changes in speech; difficulty breathing

- Skin – pain; increased sensitivity; pus and/or blood discharge

- Breast – slow growing lump that may be tender or cause pain.

What are the risk factors?

The cause of ACC is not known. It might develop from genetic changes that happen during a person’s lifetime, rather than inheriting a faulty gene. ACC is not considered to be hereditary.

How is adenoid cystic carcinoma diagnosed?

If your doctor thinks that you may have ACC, they will take your medical history, perform a physical examination (including feeling for any lumps) and carry out certain tests depending on the location of the suspected tumour.

If the results suggest that you may have ACC, your doctor will refer you to a specialist for more tests. These can include:

CT (computerised tomography) and/or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans

Special machines are used to scan and create pictures of the inside of your body.

Before the scan you may have an injection of dye (called contrast) into one of your veins, which makes the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table.

For a CT scan the table moves in and out of the scanner which is large and round like a doughnut; the scan itself takes about 10 minutes. For an MRI scan the table slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends; the scan takes a little longer, about 30–90 minutes to perform. Both scans are painless.

PET (positron emission tomography) scan

Before the scan you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) solution. Many cancer cells will show up brighter on the scan. You will be asked to sit quietly for 30–90 minutes to allow the glucose to move around your body, and the scan itself will take around 30 minutes to perform.

Ultrasound scan

Soundwaves are used to create pictures of the inside of your body.

For this scan, you will lie down and a gel will be spread over the affected part of your body. A small device called a transducer is moved over the area. It sends out soundwaves that echo when they hit something dense, like an organ or tumour. The images are then projected onto a computer screen. The ultrasound is painless and takes about 15 minutes.

Biopsy

Removal of some tissue from the affected area for examination under a microscope. The biopsy may be done in different ways.

In a core needle biopsy, a local anaesthetic is used to numb the area, then a thin needle is inserted into the tumour under ultrasound or CT guidance.

A fine needle aspiration (FNA) may also be used, which collects cells using a smaller needle and usually doesn’t require an anaesthetic.

A surgical biopsy is done under general anaesthesia. The surgeon will cut through the skin and take a tissue sample.

Finding a specialist

Visit The Australian and New Zealand Head and Neck Cancer Society for a directory of specialist teams in ACC care and treatment.

Rare Cancers Australia also have a directory of health professionals and cancer services across Australia.

The Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation (ACCRF) have a global list of specialists in ACC treatment, including those in Australia.

Treatment for adenoid cystic carcinoma

You will be cared for by a multi-disciplinary team of health professionals during your treatment for ACC.

The team may include a surgeon, radiation oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of radiation therapy), medical oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of systemic therapy including chemotherapy), nurse and allied health professionals such as a speech pathologist, dietitian, social worker, psychologist or counsellor and occupational therapist.

Discussion with your doctor will help you decide on the best treatment for your cancer depending on:

- where it is in your body

- whether or not the cancer has spread (stage of disease)

- your age, fitness and general health

- your preferences.

The main treatments include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. These can be given alone or in combination. Surgical removal of the cancer with follow-up radiation is the standard treatment for ACC where there is a primary tumour.

Surgery

Surgery is usually the most effective treatment for ACC if the cancer can be safely removed. Surgery usually involves removing the cancer and some healthy tissue around the cancer. This is called a wide local excision. The healthy tissue is removed to help reduce the risk of the cancer coming back in that area.

The extent of the operation depends on where the cancer is and how far it has spread. The surgeon will examine nearby nerves and lymph nodes and may remove them if they are involved. It can be a difficult decision to remove nerves, especially major nerves or those that control the face. It is important that your surgery is carried out by a surgeon with special expertise in this area.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses high energy rays to destroy cancer cells. It may be used effectively for ACC after surgery, to destroy any remaining cancer cells and stop the cancer coming back. It might also be used alone if surgery is not possible, for example:

- if the cancer is in a place in the body that is too hard to reach using surgery

- if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. palliative radiation for the management of pain).

A course of radiation therapy needs to be carefully planned. During your first consultation session you will meet with a radiation oncologist. At this session you will lie on an examination table and have a CT scan in the same position you will be placed in for treatment. The information from this session will be used by your specialist to work out the treatment area and how to deliver the right dose of radiation. Radiation therapists will then deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan.

Radiation therapy does not hurt and is usually given in small doses over a period of time to minimise side effects.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (sometimes just called “chemo”) is the use of drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. You may have one chemotherapy drug, or a combination of drugs. This is because different drugs can destroy or shrink cancer cells in different ways.

Chemotherapy is not commonly used for ACC. It may be considered when the cancer is advanced as part of palliative treatment or as part of a clinical trial. Your medical oncologist will discuss options with you.

Chemotherapy is given through a drip into a vein (intravenously) or as a tablet that is swallowed. It is given in treatment cycles which may be daily, weekly or monthly. For example, one cycle may last three weeks where you have the drug over a few hours, followed by a rest period before starting another cycle. The length of the cycle and number of cycles depends on the chemotherapy drugs being given.

Clinical trials

Your doctor or nurse may suggest you take part in a clinical trial. Doctors run clinical trials to test new or modified treatments and ways of diagnosing disease to see if they are better than current methods. For example, if you join a randomised trial for a new treatment, you will be chosen at random to receive either the best existing treatment or the modified new treatment. Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

You may find it helpful to talk to your specialist, GP, or clinical trials nurse. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time.

Visit Australian Cancer Trials for information or contact the Australian and New Zealand Head and Neck Cancer Society who have a special fund to support research into ACC.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Clinical Trials and Research’

Complementary therapies

Complementary therapies tend to focus on the whole person, not just the cancer, and are designed to be used alongside conventional medical treatments (such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy). They can increase your sense of control, decrease stress and anxiety, and improve your mood.

Some Australian cancer centres have developed “integrative oncology” services where evidence-based complementary therapies are combined with conventional treatments to create patient-centred cancer care that aims to improve both wellbeing and clinical outcomes.

Some complementary therapies and their clinically proven benefits are listed below:

- acupuncture – reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; improves quality of life.

- aromatherapy – improves sleep and quality of life

- art therapy, music therapy – reduce anxiety and stress; manage fatigue; aid expression of feelings

- counselling, support groups – help reduce distress, anxiety and depression; improve quality of life

- hypnotherapy – reduces pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting

- massage – improves quality of life; reduces anxiety, depression, pain and nausea

- meditation, relaxation, mindfulness – reduce stress and anxiety; improve coping and quality of life

- qi gong – reduces anxiety and fatigue; improves quality of life

- spiritual practices – help reduce stress; instil peace; improve ability to manage challenges

- tai chi – reduces anxiety and stress; improves strength, flexibility and quality of life

- yoga – reduces anxiety and stress; improves general wellbeing and quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Nutrition and exercise

If you have been diagnosed with ACC, both the cancer and treatment will place extra demands on your body. Research suggests that eating well and exercising can benefit people during and after cancer treatment.

Eating well and being physically active can help you cope with some of the common side effects of cancer treatment, speed up recovery and improve quality of life by giving you more energy, keeping your muscles strong, helping you maintain a healthy weight and boosting your mood. You can discuss individual nutrition and exercise plans with health professionals such as dietitians, exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Exercise for People Living with Cancer’

Side effects of treatment

All treatments can have side effects. The type of side effects that you may have will depend on the type of treatment and where in your body the cancer is. Some people have very few side effects while others can have more. Your specialist team will discuss all possible side effects, both short and long-term (including those that have a late effect and may not start immediately), with you before your treatment begins.

After surgery or radiation therapy to the head and neck area, you may need to adjust to significant changes. Everyone will respond differently – talk to your doctor about what to expect and try to see a speech pathologist and/or dietitian before treatment starts. Some long-term side effects of treatment to this area include:

- mouth problems, including dry mouth

- heartburn or indigestion

- taste and smell changes

- swallowing difficulties

- speech or voice changes

- breathing changes

- appearance changes.

Common side effects may include:

Surgery – Bleeding, damage to nearby tissue and organs (including nerves), drug reactions, pain, infection after surgery, blood clots, weak muscles (atrophy), lymphoedema.

Radiation therapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, hair loss, dry mouth, skin problems, lymphoedema.

Chemotherapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, bowel issues such as constipation or diarrhoea, mouth sores, skin and nail problems, increased chance of infections, loss of fertility, early menopause.

Life after treatment

Once your treatment has finished, you will have regular check-ups to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back.

Ongoing surveillance for ACC involves a schedule of ongoing blood tests and scans. Let your doctor know immediately of any health problems between visits.

Some cancer centres work with patients to develop a “survivorship care plan” which includes a summary of your treatment, sets out a schedule for follow-up care, lists any symptoms and long-term side effects to watch out for, identifies any medical or emotional problems that may develop and suggests ways to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Maintaining a healthy body weight, eating well and being active are all important. If you don’t have a care plan ask your specialist for one and make sure a copy is given to your GP and other health care providers.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people ACC does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. It may also spread to other parts of the body after a couple of years. If the cancer does come back, treatment will depend on where the cancer has returned to in your body and may include a mix of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment. Palliative care can be provided in the home, in a hospital, in a palliative care unit or hospice, or in a residential aged care facility.

When cancer is no longer responding to active treatment, it can be difficult to think about how and where you want to be cared for towards the end of life. But it’s essential to talk about what you want with your family and health professionals, so they know what is important to you. Your palliative care team can support you in having these conversations.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people are able to get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council

13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.