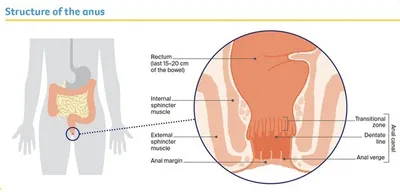

The anus

The anus is the opening at the end of the large bowel.

It is made up of the last few centimetres of the bowel (anal canal) and the skin around the opening (anal margin). During a bowel movement, the anus muscles (sphincters) relax to release the solid waste matter known as faeces, stools or poo.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about anal cancer are below.

What is anal cancer?

Anal cancer affects the tissues of the anus. It can start in any part of the anus including the anal margin, anal canal and transitional zone.

Cancer is a disease of the cells. Cells are the body’s basic building blocks – they make up tissues and organs. The body constantly makes new cells to help us grow, replace worn-out tissue and heal injuries.

Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, with each new cell replacing one lost. Sometimes cells become abnormal and keep growing. These abnormal cells may form a lump or tumour. If the cells in a tumour are cancerous, they can spread through the bloodstream or lymph vessels and form another tumour at a new site. This new tumour is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

How common is anal cancer?

Every year, about 615 people are diagnosed with anal cancer in Australia. It is more common over the age of 50 and more women than men are diagnosed with it. The number of people diagnosed with anal cancer has increased over recent decades.

While anal cancer is rare (fewer than 2 cases in 100,000 people), rates are more than 40 times higher in gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men.

For more specific information:

What are the types of anal cancer?

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Most anal cancers are SCCs. These start in the flat (squamous) cells that line much of the anus. The term “anal cancer” commonly refers to SCCs, and this information focuses on this type of anal cancer.

Adenocarcinoma

This is a less common type of anal cancer. Adenocarcinomas can start in cells that line the

upper part of the anus near the rectum or in the glands that release secretions into the anal

canal. It can be treated in a similar way to bowel cancer.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Bowel Cancer’

Skin Cancer

In rare cases, SCCs can affect the skin just outside the anus. These are called anal margin SCCs. If they are not too close to the sphincter muscles, they can be treated in a similar way to SCCs on other areas of the skin.

What are the risk factors?

About 90% of anal cancers are caused by infection with specific strains of a very common virus called human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV can infect the surface of different areas, including the anus, cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, mouth and throat. Some HPV strains cause anal and genital warts.

About 4 out of 5 people will become infected with one type of genital HPV at some time in their lives. Unless they are tested, most people won’t know they have an HPV infection as it usually doesn’t cause symptoms. If cancer develops, it usually appears many years after the first infection.

Other risk factors for anal cancer include:

- having a weakened immune system, e.g. because of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, an organ transplant or an autoimmune disease such as coeliac disease, lupus or Graves disease

- being a receptive partner (“bottom”) in anal sex

- having anal or genital warts

- having had an abnormal cervical screening test

- having had cancer of the cervix, vulva or vagina

- smoking tobacco

- having unprotected sex

- having many sex partners

- being aged over 45.

People diagnosed with anal cancer may not have any of these risk factors.

Vaccination can prevent infection with HPV. The most common HPV vaccine used in Australia protects against cancers linked with HPV including anal, cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancers. Under the national HPV vaccination program, free vaccines are provided at school for all children aged 12–13. Visit HPV Vaccine to see who else is eligible for free vaccination.

What are the symptoms?

In its early stages, anal cancer often has no obvious symptoms, but symptoms can include:

- blood or mucus in faeces or on toilet paper

- itching, discomfort or pain around the anus, or a feeling of fullness, discomfort or pain in the rectum

- a lump near the edge, or inside, of the anus

- ulcers around the anus

- difficulty controlling bowel movements

- feeling that the bowel hasn’t emptied completely.

Not everyone with these symptoms has anal cancer. Other conditions, such as piles (haemorrhoids) or tears in the anal canal (anal fissures), can also cause these changes. If the symptoms are ongoing, see your general practitioner (GP) for a check-up.

How is anal cancer diagnosed?

The main tests for diagnosing anal cancer are a physical examination and endoscopy with biopsy.

Physical examination – The doctor inserts a lubricated gloved finger into your anus to feel for any lumps or swelling. This is called a digital anorectal examination (DARE).

Endoscopy – The doctor inserts a narrow instrument called a sigmoidoscope or colonoscope into the anus to see the lining of the anal canal. This may be done under a light general anaesthetic (sedation).

Biopsy – Only a tissue sample (biopsy) from the area can be used to diagnose cancer. This sample may be collected during the endoscopy, and then sent to a pathologist who will check it for cancer under a microscope.

Imaging scans – These are used to check if cancer has spread. Scans may include a pelvic MRI, an ultrasound, a CT scan or, less often, a PET-CT scan.

Staging anal cancer

Staging describes how far the cancer has spread. Knowing the stage helps doctors plan the best treatment for you. Anal cancer is staged using the TNM (tumour–nodes–metastasis) system.

T (tumour) 0–4

Indicates how far the tumour has grown into the bowel wall and nearby areas. T1 is a smaller tumour (2 cm or less); T4 can be any size but growing into surrounding organs.

N (nodes) 0–1c

Shows if the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (small glands): N0 means no cancer is in the lymph nodes; N1 means cancer is in the lymph nodes around the rectum, groin and/or pelvis. N1 can be further divided into a, b or c, depending on which lymph nodes the cancer has spread to.

M (metastasis) 0–1

Shows if the cancer has spread to other, distant parts of the body: M0 means cancer has not spread; M1 means cancer has spread.

The diagnosis of anal cancer was a huge shock and overwhelming. Being poked and prodded there was initially intimidating. But my focus was on doing everything I could to get well.

Treatment for anal cancer

Because anal cancer is rare, you may want to talk to your doctor about being referred to a specialist treatment centre with a multidisciplinary team (MDT) that regularly manages this cancer.

The MDT will work out the best treatment, depending on the type and location of the cancer; if the cancer has spread; your health; and your own preferences. You may also want to get a second opinion from another specialist team to confirm or explain the treatment options.

Understanding the disease, the available treatments, possible side effects and any extra costs can help you weigh up the treatment options and make a well-informed decision.

Most anal cancers are treated with a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy, which is known as chemoradiation or chemoradiotherapy. Surgery may also be used in some cases.

If you have to travel for treatment, there may be a program in your state or territory to refund some of the travel and accommodation costs. For more information, talk to your doctor, nurse or hospital social worker, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Chemoradiation

This is the most common treatment for anal cancer. It combines a course of radiation therapy with some chemotherapy sessions. It can be very effective and allow you to avoid surgery to remove your anal canal. Chemotherapy makes the cancer cells more sensitive to the radiation therapy.

For anal cancer, a typical treatment plan might involve a session of radiation therapy every weekday for several weeks, as well as chemotherapy on some days during the first and fifth weeks. This combined approach allows for lower doses of radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy – Also known as radiotherapy, this treatment uses targeted radiation, such as x-ray beams, to kill or damage cancer cells. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most commonly used type of radiation for anal cancer.

EBRT focuses radiation from outside the body onto the cancer, with treatment carefully planned so as little harm as possible is done to normal body tissue around the cancer. For treatment, you lie under a machine that delivers radiation to the targeted area. It takes 10–20 minutes to set up the machine, but the treatment takes only a few minutes and is painless. You will usually be able to go home afterwards.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Radiation Therapy’

Chemotherapy – This is the treatment of cancer with anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs. It aims to kill cancer cells while doing the least possible damage to healthy cells. For anal cancer, the drugs are usually given into a vein through an intravenous (IV) drip on the first day and then in tablet form for the rest of the treatment.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Chemotherapy’

Side effects of chemoradiation

Both radiation therapy and chemotherapy can have side effects. These can occur during or soon after the treatment (early side effects), or many months or years later (late side effects).

Early side effects – These usually settle down in the weeks after treatment. They may include:

- tiredness (fatigue)

- appetite loss, nausea and vomiting – nausea and vomiting are usually prevented with medicines

- bowel changes, such as diarrhoea and more frequent, urgent or painful bowel movements

- passing urine more often, experiencing pain when urinating, or leaking urine (incontinence)

- skin changes, with redness, itching, peeling or blistering around the anus, genital areas and groin – your team will recommend creams for this

- pain in the anal region – talk to your treatment team about a pain management plan

- increased risk of infection – if you have a temperature over 38°C, contact your doctor or go to a hospital emergency department

- loss of pubic hair.

Late side effects – These can occur several months, or even years, after treatment ends. They vary a lot from person to person, but may include:

- bowel changes, with scar tissue in the anal canal or rectum leading to ongoing frequent, urgent or painful bowel movements

- dryness, shortening or narrowing of the vagina (vaginal stenosis) – vaginal dilators may be

recommended during treatment and after, as well as vaginal moisturisers and lubricants - narrowing of the anal canal (anal stenosis) – anal dilators may be recommended during and after treatment, and can help reduce the narrowing

- bladder incontinence – radiation therapy can damage and weaken the bladder leading to

leaking or incontinence - impacts on sexuality, including painful intercourse, loss of pleasure, or difficulty getting erections.

- effects on the ability to have children (fertility).

Download our booklet ‘Sex, Intimacy and Cancer’

Effects on fertility

Chemoradiation for anal cancer can affect your ability to have children (fertility), which may be temporary or permanent. If you may want to have children in the future, talk to your doctor about what options are available.

Surgery

Surgery may be used to treat very early anal cancer or in a small number of other situations. Your cancer specialists will explain whether surgery is recommended for you.

Surgery for very small tumours – An operation called local excision can remove very small tumours near the entrance of the anus (anal margin) if they are not too close to the muscles of the anus. The surgeon will give you a local or general anaesthetic and insert an instrument into the anus to remove the tumours. Once the wound heals, the anal canal will still work in the normal way.

Abdominoperineal resection – For most people with anal cancer, chemoradiation is the main treatment. If you cannot have chemoradiation because you have previously had radiation therapy to the pelvic region, or if anal cancer comes back, a major operation called an abdominoperineal resection may be an option.

In an abdominoperineal resection, the anus, rectum and part of the colon (large bowel) are removed. The surgeon uses the remaining colon to create a permanent stoma, which is an opening in the abdomen that allows faeces to leave the body. A stoma bag is worn on the outside of the body to collect the faeces.

See our ‘Understanding Bowel Cancer’ booklet for more information about this operation and stomas.

Recovery after surgery

Your recovery time will depend on the type of surgery you had and your general health.

You will be given medicine to control any pain you may experience. Do not put anything into your anus after surgery until your doctor says the area is healed (usually 6–8 weeks).

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment, you will need check-ups every 3–12 months for several years to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back. Between visits, let your doctor know immediately if you have new symptoms in the anal region or any other health problems.

Sex and desire after treatment

How you might feel

It is common to feel shocked and upset about having cancer in such an intimate area of your body. Changes to the look and feel of your body can make you feel self-conscious and have less interest in sex. You could also feel embarrassed and scared to ask for help. These feelings are natural. A side effect of chemoradiation can also be less interest in sex.

Download our booklet ‘Emotions and Cancer’

Possible side effects

Side effects of chemoradiation can cause sex to be painful. Pelvic radiation therapy can narrow the vagina and lead to thinning of the walls and dryness. The skin inside the anus may become sensitive. Ask your doctor about dilators, lubricants and moisturiser. Anal penetration may also not be possible, at least for a period of time.

Explore different ways

How you used to enjoy having sex may be more difficult or not possible after treatment. This can be upsetting, but you can find new ways to become aroused. You may want to try switching sexual roles; oral sex; exploring different erogenous zones; mutual masturbation; genital rubbing; personal lubricants; vibrators and other sex toys.

Download our booklet ‘Sex, Intimacy and Cancer'

Talk to someone

It can help to share how you’re feeling about the diagnosis and treatment side effects, and how it may be impacting your relationships and sex life. Talking with a specialist such as a counsellor, sex therapist or psychologist can help. Ask your doctor for a referral, and you can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

If the cancer comes back

For some people, anal cancer does come back after treatment. This is known as a recurrence.

Depending on where the cancer comes back, treatment may include surgery, chemoradiation

or chemotherapy.

In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment.