The gall bladder

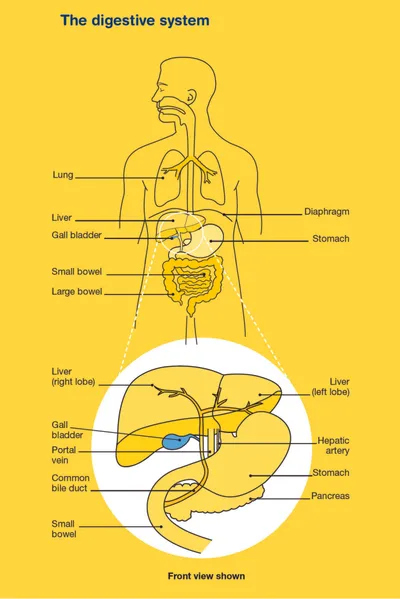

The gall bladder is a small, pear-shaped organ on the right side of the abdomen.

It is part of the digestive system and sits under the liver. It stores bile that is made by the liver. Bile is passed through small tubes (bile ducts) into the small bowel (small intestine) after eating and helps to break down fats.

What is gall bladder cancer?

Gall bladder cancer occurs when cells in the gall bladder become abnormal and keep growing to form a mass or lump called a tumour. The tumour type is defined by the particular cells that are affected.

The most common type is adenocarcinoma, which starts in epithelial cells (which release mucus) that line the inside of the gall bladder. These make up about 85% of all gall bladder cancers. Other types of gall bladder cancer include:

- squamous cell carcinoma, from squamous cells (skin-like cells)

- sarcoma, from connective tissue (which support and connect all the organs and structures of the body)

- lymphoma, from lymph tissue (part of the immune system which protects the body).

Malignant (cancerous) tumours have the potential to spread to other parts of the body through the blood stream or lymph vessels and form another tumour deposit at a new site. This new tumour is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

How common is gall bladder cancer?

Gall bladder cancer is rare. About 891 Australians are diagnosed each year with gall bladder or bile duct cancer (about 3 cases per 100,000 people). It is more likely to be diagnosed in women than men, and people aged over 65 years.

What are the symptoms and the risk factors?

Gall bladder cancer can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages as it doesn’t usually cause symptoms.

Sometimes, gall bladder cancer is found when the gall bladder is removed for another reason, such as gallstones. But most people who have surgery for gallstones do not have gall bladder cancer.

Gall bladder cancer is sometimes suspected when there is a large gall bladder polyp (greater than 1 cm) or a calcified gall bladder.

If symptoms do occur they can include:

- abdominal pain, often on the upper right side

- nausea (feeling sick) or vomiting

- jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), causing dark urine (wee), pale bowel movements (poo) and severe itching without any visible skin rash

- general weakness or fatigue

- a lump in the abdomen

- unexplained weight loss

- fever.

What are the risk factors?

The cause of gall bladder cancer is not known in most cases, but risk factors can include:

- having had gallstones or inflammation of the gall bladder (although the majority of people with gallstones will never develop gall bladder cancer)

- family history of gall bladder cancer can result in a small increase in risk (first-degree relative such as mother, father, sibling or child). The majority of people with gall bladder cancer, however, will not have a family history

- other gall bladder and bile duct conditions and abnormalities, such as gall bladder polyps, choledochal cysts (bile-filled cysts) and calcified gall bladder (also known as porcelain gall bladder).

How is gall bladder cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor thinks that you may have gall bladder cancer, they will perform a physical examination and carry out certain tests.

If the results suggest that you may have gall bladder cancer, your doctor will refer you to a specialist who will carry out more tests. These tests may include:

Blood tests

Blood tests including a full blood count (to measure your white blood cells, red blood cells, platelets), liver function tests (to measure chemicals that are found or made in your liver) and tumour markers (to measure chemicals produced by cancer cells).

Ultrasound scan

Soundwaves are used to create pictures of the inside of your body. For this scan, you will lie down and a gel will be spread over the affected part of your body. A small device called a transducer is moved over the area by an ultrasound radiographer. The transducer sends out soundwaves that echo when they encounter something dense, like an organ or tumour. The ultrasound images are then projected onto a computer screen. An ultrasound is painless and takes about 15–20 minutes.

CT (computerised tomography) and/or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans

Special machines are used to scan and create pictures of the inside of your body. Before the scan you may have an injection of dye (called contrast) into one of your veins, which makes the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table.

For a CT scan the table moves in and out of the scanner which is large and round like a doughnut; the scan itself usually takes about 10–30 minutes.

For an MRI scan the table slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends; the scan takes a little longer, about 30–90 minutes to perform. Both scans are painless.

Diagnostic laparoscopy

A thin tube with a camera on the end (laparoscope) is inserted under sedation into the abdomen so the doctor can view inside.

Cholangiography

An x-ray of the bile duct to see if there is any narrowing or blockage and help plan surgery to remove the gall bladder. For an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), the doctor inserts a flexible tube with a camera on the end (endoscope) down your throat into your small intestine while you are sedated to view your gut and take images.

Biopsy

A Biopsy is the removal of some tissue from the affected area for examination under a microscope. In the gall bladder, a biopsy may be done during a laparoscopy or cholangiography. Otherwise a needle biopsy is done, where a local anaesthetic is used to numb the area, then a thin needle is inserted into the tumour under ultrasound or CT guidance.

Finding a specialist

Rare Cancers Australia have a directory of health professionals and cancer services across Australia.

Treatment for gall bladder cancer

You will be cared for by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of health professionals during your treatment for gall bladder cancer.

The team may include a surgeon, pathologist (to interpret the results of blood tests and biopsies), radiologist, radiation oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of radiation therapy), medical oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of systemic therapy which includes chemotherapy), gastroenterologist (to treat disorders of the digestive system), nurse and allied health professionals such as a dietitian, social worker, psychologist or counsellor, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Discussion with your doctor will help you decide on the best treatment for your cancer depending on:

- the type of cancer you have

- whether or not the cancer has spread (stage of disease)

- your age, fitness and general health

- your preferences.

The main treatments for gall bladder cancer include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. These can be given alone or in combination. This is called multi-modality treatment.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for gall bladder cancer, especially for people with early-stage disease where the gall bladder can be completely removed.

Surgery to remove the gall bladder is called a cholecystectomy. Often surrounding tissue including lymph nodes, adjacent bile ducts and part of the liver will also be removed if gall bladder cancer is suspected. Surgery may be performed as either open surgery or keyhole (laparoscopic) surgery. If the tumour has been found after the gall bladder has been removed for another reason, further surgery may be required.

If the cancer has spread and the tumour is pressing on, or blocking, the bile duct, you may need a stent (small tube made of either plastic or metal). This holds the bile duct open and allows bile to flow into the small bowel again. Stents are placed under x-ray guidance or during an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

The extent of the surgery depends on the location and stage of the tumour. Your surgeon will discuss the type of operation you may need and the side effects and risks of surgery.

External beam radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses high energy rays to destroy cancer cells, where the radiation comes from a machine outside the body. It is often given with chemotherapy in a treatment known as chemoradiation. It may be used for gall bladder cancer:

- after surgery, to destroy any remaining cancer cells and stop the cancer coming back

- if the cancer can’t be removed with surgery

- if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. palliative radiation for the management of symptoms such as pain).

A course of radiation therapy needs to be carefully planned. During your first consultation session you will meet with a radiation oncologist who will take a detailed medical history and arrange a planning session. At the planning session (known as CT planning or simulation) you will need to lie still on an examination table and have a CT scan. You will be placed in the same position you will be placed in for treatment. The information from the planning session will be used by your specialist to work out the treatment area and how to deliver the right dose of radiation. Radiation therapists will then deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan.

Radiation therapy does not hurt and is usually given in small doses over a period of time to minimise side effects. Each treatment only takes a few minutes but the set-up time can take longer.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (sometimes just called “chemo”) is the use of drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. You may have one chemotherapy drug, or be given a combination of drugs. This is because different drugs can destroy or shrink cancer cells in different ways. Your treatment will depend on your situation and the stage of your tumour. Your medical oncologist will discuss your options with you.

Chemotherapy is usually given through a drip into a vein (intravenously) or as a tablet that is swallowed. Your medical oncologist will discuss your options with you.

Chemotherapy is commonly given in treatment cycles which may be daily, weekly or monthly. For example, one cycle may last three weeks where you have the drug over a few hours, followed by a rest period, before starting another cycle. The length of the cycle and number of cycles depends on the chemotherapy drugs being given.

Clinical trials

Your doctor or nurse may suggest you take part in a clinical trial. Doctors run clinical trials to test new or modified treatments and ways of diagnosing disease to see if they are better than current methods. For example, if you join a randomised trial for a new treatment, you will be chosen at random to receive either the best existing treatment or the modified new treatment. Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

You may find it helpful to talk to your specialist, clinical trials nurse or GP, or to get a second opinion. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time.

Visit Australian Cancer Trials for more information or contact the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG).

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Clinical Trials and Research’

Complementary therapies and integrative oncology

Complementary therapies are designed to be used alongside conventional medical treatments (such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) and can increase your sense of control, decrease stress and anxiety, and improve your mood.

Some Australian cancer centres have developed “integrative oncology” services where evidence-based complementary therapies are combined with conventional treatments to create patient-centred cancer care that aims to improve both wellbeing and clinical outcomes.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

- Some complementary therapies and their clinically proven benefits are listed below:

- acupuncture – reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; improves quality of life

- aromatherapy – improves sleep and quality of life

- art therapy, music therapy – reduce anxiety and stress; manage fatigue; aid expression of feelings

- counselling, support groups – help reduce distress, anxiety and depression; improve quality of life

- hypnotherapy – reduces pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting

- massage – improves quality of life; reduces anxiety, depression, pain and nausea

- meditation, relaxation, mindfulness – reduce stress and anxiety; improve coping and quality of life

- qi gong – reduces anxiety and fatigue; improves quality of life

- spiritual practices – help reduce stress; instil peace; improve ability to manage challenges

- tai chi – reduces anxiety and stress; improves strength, flexibility and quality of life

- yoga – reduces anxiety and stress; improves general wellbeing and quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Alternative therapies are therapies used instead of conventional medical treatments. These are unlikely to be scientifically tested and may prevent successful treatment of the cancer. Cancer Council does not recommend the use of alternative therapies as a cancer treatment.

Nutrition and exercise

If you have been diagnosed with gall bladder cancer, both the cancer and treatment will place extra demands on your body. Research suggests that eating well and exercising can benefit people during and after cancer treatment.

If you have had your gall bladder removed, bile made by the liver will no longer be stored between meals. Bile instead will flow directly from your liver into your small intestine and there will still be enough bile produced for normal digestion. You should still be able to eat a normal diet after your gall bladder is removed, but it’s a good idea to avoid high-fat foods for a few weeks after surgery while your body adjusts.

Eating well and being physically active can help you cope with some of the common side effects of cancer treatment, speed up recovery and improve quality of life by giving you more energy, keeping your muscles strong, helping you maintain a healthy weight and boosting your mood.

You can discuss individual nutrition and exercise plans with health professionals such as dietitians, exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Exercise for People Living with Cancer’

Side effects of treatment

All treatments can have side effects. The type of side effects that you may have will depend on the type of treatment and where in your body the cancer is. Some people have very few side effects and others have more. Your specialist team will discuss all possible side effects, both short and long-term (including those that have a late effect and may not start immediately), with you before your treatment begins.

One issue that is important to discuss before you undergo treatment is fertility, particularly if you have been diagnosed at a younger age and want to have children in the future.

Download our booklet ‘Fertility and Cancer’

Common side effects may include:

Surgery – Bleeding, damage to nearby tissue and organs (including liver failure and bile leakage), pain, infection after surgery, blood clots, weak muscles (atrophy), lymphoedema.

Radiation therapy – Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, liver damage, bowel issues such as diarrhoea, skin problems, loss of fertility, early menopause.

Chemotherapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, bowel issues such as diarrhoea, hair loss, mouth sores, skin and nail problems, increased chance of infections, loss of fertility, early menopause.

After treatment for gall bladder cancer (especially surgery), you may need to adjust to changes in the digestion of food or bowel function, in particular diarrhoea. These changes may be temporary or ongoing and may require specialised help. If your gall bladder has been removed, you can still break down fats in your small intestine. The bile simply flows directly from your liver to your duodenum, rather than passing through your gall bladder first. If you experience problems, talk to your GP, specialist doctor, specialist nurse or dietitian.

Life after treatment

Once your treatment has finished, you will have regular check-ups to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back.

Ongoing surveillance for gall bladder cancer involves a schedule of ongoing scans, and physical examinations. Let your doctor know immediately of any health problems between visits.

Some cancer centres work with patients to develop a “survivorship care plan” which includes a summary of your treatment, sets out a schedule for follow-up care, lists any symptoms and long-term side effects to watch out for, identifies any medical or emotional problems that may develop and suggests ways to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Maintaining a healthy body weight, eating well and being active are all important.

If you don’t have a care plan ask your specialist for one and make sure a copy is given to your GP and other health care providers.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people gall bladder cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. If this happens, treatment will depend on where the cancer has returned to in your body and may include a mix of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment. Palliative care treatment can be provided in the home, in a hospital, in a palliative care unit or hospice, or in a residential aged care facility.

When cancer is no longer responding to active treatment, it can be difficult to think about how and where you want to be cared for towards the end of life. But it’s essential to talk about what you want with your family and health professionals, so they know what is important to you. Your palliative care team can support you in having these conversations.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people are able to get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council

13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.