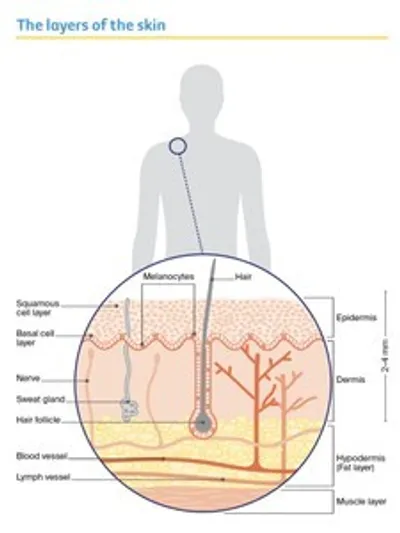

The skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body.

It acts as a barrier to protect the body from injury, control body temperature and prevent loss of body fluids. The 2 main layers of the skin are the epidermis and dermis.

Epidermis

This is the top, outer layer of the skin. It has 3 main types of cells:

Squamous cells – These flat squamous cells are packed tightly together to make up the top layer of skin. They form the thickest layer of the epidermis.

Basal cells – These block-like basal cells make up the lower layer of the epidermis. The body makes new basal cells all the time. As they age, they move up into the epidermis and flatten out to form squamous cells.

Both basal and squamous cells are keratinocyte cells, which is why non-melanoma skin cancers are sometimes called keratinocyte cancers.

Melanocytes – These cells sit between the basal cells and produce a dark pigment called melanin that gives skin its colour. When skin is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, melanocytes make melanin to try to protect the skin from getting burnt. Melanocytes are also found in non-cancerous spots on the skin called moles or naevi.

Dermis

This layer of the skin sits below the epidermis. The dermis is made up of fibrous tissue and contains the roots of hairs (follicles), sweat glands, blood vessels, lymph vessels and nerves.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about skin cancer are below.

What is skin cancer?

Skin cancer is the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in the skin. The 3 main types are:

- basal cell carcinoma (BCC) – about 2 out of 3 skin cancers

- squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) – about 1 in 3 skin cancers

- melanoma – about 1 in 100 skin cancers.

BCC and SCC – These are also called non-melanoma skin cancer or keratinocyte cancer. They are far more common than melanoma and make up about 99% of skin cancers.

Melanoma – This starts in the melanocytes and makes up 1–2% of all skin cancers. It is the most serious form of skin cancer because it is more likely to spread to other parts of the body,

especially if not found and treated early.

This information is only about non-melanoma (keratinocyte) skin cancers.

Rare types of skin cancer – These include Merkel cell carcinoma and angiosarcoma. They are treated differently from BCC and SCC. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

What are the different types of Non-melanoma (keratinocyte) skin cancer?

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

The most common signs – a pink, pearl-like, flat or raised lump; shiny, pale/bright/dark pink scaly area.

What it may feel like – can be itchy, inflamed, ulcerate, weep, ooze, scab or bleed; may “heal” then inflame/bleed/itch again.

Where it is most often found – sun-exposed areas, such as head, face, neck, shoulders, arms and legs, but may be anywhere.

How it usually grows – slowly over months or years; very rarely spreads to other parts of the body; may grow deeper, invade nerves and tissue, making treatment more difficult.

The risk factors – having had a BCC increases the risk of developing another BCC.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

The most common signs – a thick scaly lesion; a fast-growing pink lump; a red, scaly or crusted spot.

What it may feel like – can become inflamed and often feel tender to the touch; may occasionally bleed.

Where it is most often found – sun-exposed areas, such as head, neck, hands, forearms and lower legs, but can start anywhere.

How it usually grows – quickly over weeks or months; called invasive SCC if it invades past skin’s top layer; untreated, may spread to other parts of the body (metastatic SCC).

The risk factors – SCCs on head, neck, lips and ears, and in people immunosuppressed, are more likely to spread.

Refer to page 9 of our 'Understanding Skin Cancer' book for images.

What about other skin spots?

Some spots that appear on the skin are not cancerous. We have given examples of the most common ones here, but these skin spots can vary in how they look. If you are concerned about any mark or growth on your skin, see a general practitioner (GP) or a dermatologist to have it checked.

Sunspot (actinic or solar keratosis)

- flat, scaly spot that feels rough; often the colour of your skin or red

- usually appears on skin that is most exposed to the sun, such as the head, neck, hands, forearms and legs

- a sign of too much sun exposure and a marker of sun damage; a risk factor for skin cancer

- may on rare occasions develop into SCC skin cancer

- more common in people over 40, but anyone of any age can develop them

Age spot (seborrhoeic keratosis)

- raised area on the skin that feels rough; may look and feel a bit like a wart

- may be itchy or bleed if scratched

- may range in colour from light to very dark brown

- found anywhere on the body apart from the palms of the hands and soles of the feet

- may look similar to a skin cancer or sunspot

- very common but harmless

Mole (naevus)

- brown, black or the same colour as your skin; usually round or oval

- a normal skin growth that develops when melanocytes grow in groups

- some people have lots of moles – this can run in families

- too much sun exposure, especially as a child, may increase the number of moles

- very common

- a risk factor for melanoma; people with lot of moles may have a higher risk of developing melanoma

Irregular mole (dysplastic naevus)

- a larger mole with an irregular shape and uneven colour

- just as with moles, people with lots of irregular moles may have a higher risk of developing melanoma

Refer to pages 10 and 11 of our 'Understanding Skin Cancer' book for images.

"I have lots of age spots and moles. I find it hard, but I try to keep track of what they look like, and any changes. But I make sure to get a skin check by a doctor every year too. Last check they found an SCC, but luckily it was treated early.” GWEN

What causes skin cancer?

Over 95% of skin cancers are caused by exposure to UV radiation. When unprotected skin is exposed to UV radiation, how the cells look and behave can change.

Across Australia, the UV levels can do damage to unprotected skin most of the year, not just in warmer months. Even when the UV levels are moderate they can still do damage. UV radiation can’t be seen or felt. It isn’t related to the temperature or whether it’s sunny or cloudy. UV radiation can cause sunburn; premature skin ageing; and damage to skin cells, which can lead to skin cancer.

You can’t always see sun damage that’s happened to the skin – and it can happen long before you get sunburnt or develop a tan. The damage also adds up over time and can’t be reversed.

You can check the UV levels in your local area on the SunSmart app.

See information on how to properly protect your skin from the sun and prevent skin cancer.

How common is skin cancer?

Australia has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in the world. About 2 out of 3 Australians will be diagnosed with some form of skin cancer before the age of 70.

Non-melanoma (keratinocyte) skin cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in Australia. Over 1 million treatments are given each year in Australia for non-melanoma skin cancers. BCC can develop in young people, but it is more common in people over 40. SCC occurs mostly in people over 50.

Who is at risk?

Anyone of any age can develop skin cancer but it becomes more common as you get older. Many factors can increase your risk of skin cancer, including having:

- pale or freckled skin, especially if it burns easily and doesn’t tan

- red or fair hair and light-coloured eyes (blue or green)

- unprotected exposure to UV radiation, particularly a pattern of short, intense periods of sun exposure and sunburn, such as on weekends and holidays

- actively having tanned, sunbaked or used solariums

- worked outdoors or spent a lot of time outside (e.g. gardening or golfing)

- been exposed to arsenic

- a weakened immune system – this may be from having leukaemia or lymphoma or using medicines that suppress the immune system (e.g. for rheumatoid arthritis, another autoimmune disease or for an organ transplant)

- lots of moles, or lots of moles with an irregular shape and uneven colour

- a previous skin cancer or a family history of skin cancer

- certain skin conditions such as sunspots, because they show that you have had a lot of skin damage from exposure to the sun

- smoked cigarettes, as smoking has been linked to a possible increase in skin cancer risk.

People with brown, black, olive or very dark skin colour often have more protection against UV radiation because their skin produces more melanin than fair skin does. However, they can still develop skin cancer.

How do I check my skin?

In a room with good light, undress completely and use a full-length mirror to check your whole body. To check areas that are difficult to see, use a handheld mirror or ask someone to help you.

If there any changes to your skin, if you notice something new, or you are worried about a spot you see, make an appointment with your doctor straightaway. You will have a better outcome if the skin cancer is found and treated early. For more information on checking your skin, visit SunSmart.

How do I spot a skin cancer?

Most skin cancers are self-detected. If you know what changes to watch for, you’ll be more likely to find a skin cancer early.

Skin cancers don’t all look the same, but there are some signs to look out for, including:

- a spot that looks and feels different from other spots on your skin

- a spot that has changed size, shape, colour or texture

- a spot that is tender or sore to touch

- a sore that doesn’t heal within a few weeks

- a sore that is itchy or bleeds.

Getting to know your skin will help you notice any new or changing spots. Make a time to regularly check your skin. You could try having a calendar reminder for the first day of the month, or you may want to do a check at the change of each season.

There is no set guideline on how often to check for skin cancer, but if you have had a skin cancer or are at greater risk of developing skin cancer, your doctor can tell you how often to check your skin.

Can smartphone apps help to detect skin cancer?

Some smartphone apps let you photograph your skin at regular intervals and compare the photos to check for changes. These apps may be a way to record any spot you are worried about or remind you to check your skin. However, research shows that apps cannot reliably detect skin cancer. If you notice a spot that worries you, make an appointment with your doctor straightaway.

Which health professionals will I see?

You may see one or more of the following doctors:

GP – Many GPs diagnose and treat people with BCC and SCC skin cancers. They may perform surgery, cryotherapy or prescribe topical treatments. Some GPs have extra training related to skin cancer. Before choosing a GP, you can ask what experience or qualifications they have with skin cancer. You may see a GP at a general practice, medical centre or skin cancer clinic. Skin cancer clinics are run by GPs with an interest in skin cancer. A GP may refer you to a dermatologist, surgeon or radiation or medical oncologist for larger areas or cancers that are hard to remove. If there’s a waiting list and spot of concern, your GP can ask for an earlier appointment.

Dermatologist – A doctor who diagnoses, treats and manages skin conditions and skin cancer. They perform surgery, cryotherapy and prescribe topical treatments.

Radiation or medical oncologist – A radiation oncologist prescribes and oversees a course of radiation therapy, which may be used to treat some skin cancers. A medical oncologist prescribes cancer drug therapies, which may be used for a small number of (usually) advanced skin cancers.

Surgeon – Some skin cancers are treated by surgeons:

- Surgical oncologists specialise in treating cancer with surgery; they manage complex skin cancers, including those that have spread to the lymph nodes.

- Reconstructive (plastic) surgeons are trained in surgical oncology and in complex reconstructive techniques for more difficult to treat areas (e.g. the nose, lips, eyelids and ears).

How is skin cancer diagnosed?

Tests you may have

Physical examination

If you notice any changes to your skin, your doctor will look carefully at your skin and examine any spots you think are unusual. The doctor will use a handheld magnifying instrument called a dermatoscope to examine the spots more closely. They will also usually do a total body skin check to look at all your other moles and spots.

Skin biopsy

If the doctor feels they can diagnose the skin cancer by examining the spot, you may not need any further tests before having treatment. However, it’s not always possible to tell the difference between a skin cancer and a non-cancerous skin spot just by looking at it. If there is any doubt, the doctor may need to take a tissue sample (biopsy) to confirm the diagnosis.

A biopsy is a quick and simple procedure that is usually done in the doctor’s room. You will be given a local anaesthetic to numb the area, then the doctor will either:

- completely cut out the spot and a small amount of healthy tissue around it to be tested (excision biopsy)

- take a small piece of tissue from the spot to be tested (shave or punch biopsy).

Stitches may be used to close a larger wound. After a biopsy, your doctor will give you instructions on how to look after the wound. The biopsy skin tissue is sent to a laboratory where a pathologist examines it under a microscope. Your doctor will get the results in 1–2 weeks.

If all the cancer and a margin of healthy tissue are removed during the biopsy, this may be the only treatment you need. If the doctor has only taken a small piece from a larger spot, and this is found to be cancer, you will need to go back to have the rest of the cancerous spot removed.

Staging

The stage of a cancer describes its size and whether it has spread. BCCs rarely need staging because they don’t often spread or have other high-risk features. Only a very small number of SCCs require staging. When staging is needed, it may be because of where the SCC is, its size or because it has spread.

Usually a biopsy is the only information a doctor needs to stage skin cancer. The doctor may also feel the lymph nodes near the skin cancer to check for swelling. This may be a sign that the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes. Rarely, some people will have imaging scans to help with staging. For more information about staging, speak to your doctor.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. Your treating doctor is the best person to talk to about your prognosis. Most BCCs and SCCs are successfully treated, especially when found early.

Being told that you have cancer can come as a shock and you may feel many different emotions. If you have any concerns or want to talk to someone, see your doctor or call Cancer Council

13 11 20.

Treatment for skin cancer

Non-melanoma skin cancer is treated in different ways.

The treatment recommended by your doctors will depend on:

- the type, size and location of the cancer

- your general health

- any medicines you are taking (these may increase the risk of bleeding after surgery or delay healing)

- whether the cancer has spread to other parts of your body.

If an excision biopsy removed all the cancer, you may not need any further treatment.

Treatment of sunspots and superficial skin cancer

Many of the treatments described in this section are used for sunspots as well as skin cancers. Some sunspots may need treatment if they are causing symptoms or to prevent them becoming cancers.

Skin cancer that affects cells only on the surface of the skin’s top layer is called superficial. Treatment options for superficial BCC and SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease) include curettage and electrodesiccation (also known as cautery), freezing, topical creams and photodynamic therapy.

Surgery is not always used for superficial BCC and SCC in situ. It may be used if the diagnosis is uncertain or if the area of abnormal tissue does not respond to non-surgical treatments.

Curettage and electrodesiccation

Curettage and electrodesiccation (cautery) is used to treat some BCCs, small SCCs and areas of SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease).

The doctor will give you a local anaesthetic and then scoop out the cancer using a small, sharp, spoon-shaped instrument called a curette. Low-level heat will be applied to stop the bleeding and destroy any remaining cancer. The wound should heal within a few weeks, leaving a small, flat, round, white scar. Some people may have cryotherapy after curettage to destroy any remaining cancer cells.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy, or cryosurgery (freezing), is a procedure that uses extreme cold (liquid nitrogen) to remove sunspots, some small superficial BCCs and SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease).

The GP or dermatologist sprays liquid nitrogen onto the sunspot or skin cancer and a small area of skin around it. You may feel a burning or stinging sensation, which lasts a few minutes. The liquid nitrogen freezes and kills the abnormal skin cells and creates a wound. In some cases, the procedure may need to be repeated.

The treated area will be sore and red. A blister may form soon after. A few days later, a crust will form on the wound. The dead tissue will start to fall off 1–6 weeks later, depending on the area treated. New, healthy skin cells will grow and a scar may develop. The healed skin may look paler than the surrounding skin.

Topical treatments

Some skin spots and superficial skin cancers can be treated with creams or gels that you apply to the skin. These are called topical treatments. They may contain immunotherapy or chemotherapy drugs, and are prescribed by a doctor. Only use these treatments on the specific spots or areas that your doctor has asked you to treat. Don’t use leftover cream on spots that have not been assessed by your doctor.

Immunotherapy cream

A cream called imiquimod is a type of immunotherapy that causes the body’s immune system to destroy cancer cells. Imiquimod is used to treat sunspots and superficial BCCs. Your doctor will explain how to apply the cream and how often. For superficial BCCs, the cream is commonly applied directly to the affected area at night, usually 5 days a week for 6 weeks. Within days of starting imiquimod, the treated skin may become red, sore or tender. It may peel and scab over before it gets better.

Some people experience pain or itching in the affected area, fever, achy joints, headache and a rash. If you notice any of these more serious side effects, stop using the cream and see your doctor immediately.

Chemotherapy cream

A cream called 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a type of chemotherapy drug used to treat sunspots and sometimes SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease). 5-FU works best on the face and scalp. Your doctor will explain how to apply the cream and how often. Many people use it once or twice a day for 2–4 weeks. It may need to be used for longer for some skin cancers.

While using the cream, your skin will be more sensitive to UV radiation and you will need to stay out of the sun. The treated skin may become red, blister, peel and crack, and feel uncomfortable. These effects will usually settle within a few weeks of finishing treatment.

Radiation cream

As at December 2023, there are no guidelines or recommendations on the use of topical radiation creams such as Rhenium-188. Information on its effectiveness and side effects is needed before it may be considered a standard treatment.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses a cream that kills cancer cells when a special light is applied. It is used to treat sunspots, superficial BCCs and SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease). This treatment may have a high cost.

After gently scraping the area to remove any dry skin or crusting, the doctor applies a cream to the skin. After 3 hours, light is used to activate the cream, either using an LED light or by indirect sun exposure (daylight PDT). An LED light is usually used on the area for about 8 minutes. The area is then covered with a bandage. For skin cancers, LED PDT is usually repeated 1–2 weeks later. Daylight PDT works in a similar way – your doctor will give you instructions for how long to expose only the area with the cream to sunlight.

Side effects can include redness and swelling, which usually ease after a few days. PDT commonly causes a burning, stinging or tender feeling in the treatment area, particularly on the face. Your doctor may treat these side effects with a cold water spray or pack, or give you a local anaesthetic to help ease any discomfort.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses radiation to kill or damage cancer cells so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. It is used as the main treatment for BCCs or SCCs that are not suitable to be removed surgically, for large areas, or for people not fit enough for surgery. Sometimes radiation therapy is also used after surgery to reduce the chance of the cancer coming back or spreading.

Radiation therapy to treat skin cancer is given from outside the body (externally). It may use low-energy x-rays from a superficial x-ray machine or high-energy x-rays from a machine called a linear accelerator or LINAC. Different techniques and types of radiation may be used.

You will have a separate planning session so the radiation therapy team can work out the best position for your body during treatment. Your treatment will usually start a couple of weeks after a planning session. During each treatment session, you will lie on a table under the radiation machine. Once you are in the correct position, the machine will rotate around you to deliver radiation to the area with the cancer. The process can take 10–20 minutes, but the treatment itself takes only a few minutes.

The number of treatments vary and may take 2–7 weeks to complete. Your treatment team will consider things such as the type and position of the skin cancer and your preferences and circumstances to tailor the best treatment course. Some people have 5 sessions a week for several weeks, while others may have a much shorter course of treatment.

Skin in the treatment area may become red, dry or moist, and sore 7–10 days after treatment starts, depending on how long you have treatment. This soreness may get worse after treatment has finished but it usually improves within 6 weeks. The treatment team will suggest creams or coverings to make you more comfortable.

Hard to treat and advanced skin cancer

A very small number of SCCs and even fewer BCCs spread to lymph nodes or other areas of the body. To work out if the skin cancer has spread, your doctor will feel nearby lymph nodes and may recommend a biopsy, imaging scans or other tests. You may be referred to a cancer specialist called a medical oncologist. Your doctor or medical oncologist will explain your treatment options, which may include surgery, radiation therapy or drug therapies such as immunotherapy, targeted therapy or chemotherapy. Drug therapies such as immunotherapy may be used before or after surgery for some cancers, or used instead of surgery or radiation therapy for some people.

Life after treatment

Will I get more skin cancers?

People who’ve had skin cancer have a higher risk of getting more skin cancers. You will need regular checks with your doctor to see if the cancer has come back and to look for any new skin cancers. People who are immunosuppressed may need to be checked more often.

It’s very important to be sun smart and avoid more skin damage. As well as check-ups with your doctor, check your own skin regularly, and see your doctor if you notice a change.

Sun protection and UV

After a skin cancer diagnosis, you need to take special care to protect your skin from the sun’s UV radiation. UV radiation is not the same as sunshine – UV levels can be high on a cloudy day or at the snowfields.

Using a sunscreen daily when the UV level is forecast to be 3 or above has been shown to reduce the risk of skin cancer.

The UV index shows the intensity of the sun’s UV radiation. It can help you work out when to use sun protection. An index of 3 or above means that UV levels are high enough to damage unprotected skin and you need to use more than one type of sun protection. This includes protective clothing, a hat, sunscreen, sunglasses and seeking shade.

The recommended daily sun protection times are the times of day the UV levels are expected to be 3 or higher. The daily sun protection times will vary according to where you live and the time of year.

Some medicines and health conditions may make the skin more sensitive to UV radiation, causing it to burn or be damaged by the sun more quickly or easily. Ask your doctor if this applies to you and if there are any extra things you should do to protect your skin. You may need to use sun protection all the time, whatever the UV level is.

Vitamin D

UV radiation from the sun causes skin cancer, but it is also the best source of vitamin D. People need vitamin D for a variety of reasons, including to have healthy bones.

Most people get enough vitamin D throughout the day – even when using sun protection. When the UV index is 3 or above, you only need a few minutes outside on most days of the week to get enough vitamin D, but this will also depend on your skin colour, where you live and the time of year.

The body can absorb only a set amount of vitamin D at a time. Getting more sun won’t always increase your vitamin D levels, but it will increase your skin cancer risk. People who have had cancer should be extra careful about sun exposure. Talk to your doctor about the best way to get vitamin D while reducing your risk of skin cancer. They may suggest you stay out of the sun as much as possible and take a vitamin D tablet instead.

How to protect your skin from the sun

Most skin cancers are caused by exposure to the sun’s UV radiation. When UV levels are 3 or above, use all or as many of the following ways to protect your skin as possible. After a diagnosis of skin cancer, it is especially important to check your skin regularly and follow SunSmart behaviour.

Slip on clothing – Wear clothing that covers your shoulders, neck, arms, legs and body. Choose

closely woven fabric or fabric with a high ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) rating, and darker fabrics where possible.

Slop on sunscreen – Use an SPF 50 or higher broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen. These are higher protection and also TGA approved. Apply 20 minutes before going outdoors and reapply every 2 hours, or after swimming, sweating or any activity where it will rub off. For an adult, use 1 teaspoon for each arm, each leg, front of body, back of body, and the face, neck and ears – 7 teaspoons of sunscreen in total for all of your body.

Slap on a hat – Wear a hat that shades your face, neck and ears, such as a legionnaire, broadbrimmed or bucket hat. Check that the hat meets the Australian Standard. Choose fabric with a close weave that doesn’t let light through. Baseball caps and sun visors don’t offer full protection.

Seek shade – Use shade from trees, umbrellas, buildings or any type of canopy. UV radiation is reflective and bounces off surfaces, such as concrete, water, sand and snow, so shade should never be the only form of sun protection you use. If you can see the sky through the shade, even if the direct sun is blocked, the shade will not completely protect you from UV radiation.

Slide on sunglasses – Protect your eyes with sunglasses that meet the Australian Standard. Wraparound styles are best. Sunglasses should be worn all year round to protect both the eyes and the delicate skin around the eyes.

Don’t use solariums – Do not use solariums. Also known as tanning beds or sun lamps, solariums give off artificial UV radiation and are banned for commercial use in Australia.

Check daily sun protection times – Each day, use the free SunSmart app to check the recommended sun protection times in your local area. You can also find sun protection times at the Bureau of Meteorology or the BOM Weather app or in the weather section of daily newspapers.

Changes to your appearance

Skin cancer treatments such as surgery, curettage and electrodesiccation, and cryotherapy often leave a scar. In most cases, your doctor will do everything they can to make the scar less noticeable. Most scars will fade with time. Skin treated with radiation therapy may change in colour, and appear lighter or darker depending on your skin tone. Talk to your radiation therapy team about the best options for skincare.

Talk to your doctor or nurse about treatments that can help improve the appearance of scars, such as silicone gels and tapes and non-perfumed creams (e.g. sorbolene). Steroid injections to flatten out lumpy scars may also be an option for some people.

You may worry about how any scars look, especially on your face. Cosmetics can help cover scarring. Your hairstyle or clothing might also cover the scar. You may want to talk to a counsellor, friend or family member about how you feel after changes to your appearance.

Download our booklet ‘Emotions and Cancer’

Look Good Feel Better

Look Good Feel Better is a national program that helps people manage the appearance-related effects of cancer treatment. Workshops are run for men, women and teenagers. For information about services in your area, visit Look Good Feel Better or call 1800 650 960.

"I had skin cancer removed and a skin graft. I have a large ‘indent’ from the removal of the cancer and a large scar at the donor site. I didn’t expect the amount of pain and appearance changes.” DAVID