The eye

The human eye is a sense organ that reacts to light and allows us to see.

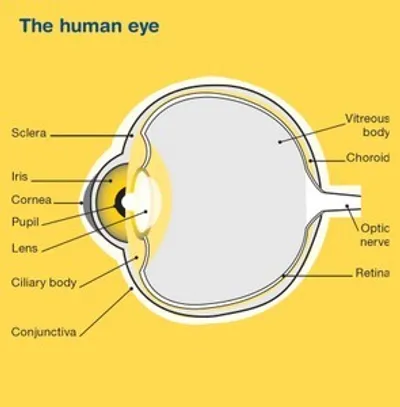

Your eye works in a similar way to a camera. When you look at an object, light passes through the cornea (the clear front layer of the eye) and enters the eyes through the pupil (the black centre of the eye). The iris (the coloured part of the eye) controls how much light the pupil lets in.

Light then passes through the lens (the clear inner part of the eye) which, together with the cornea, focuses light onto the retina. When light hits the retina (layer of tissue at the back of the eye) special cells called photoreceptors convert the light into electrical impulses that travel through the optic nerve to the brain. The brain then turns these signals into the images that you see.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about ocular melanoma are below.

What is ocular melanoma?

There are many different types of cancer that can affect the eye, but ocular melanoma is the most common. Melanoma is a type of cancer that develops in the cells of the body that produce melanin — the pigment that gives your skin its colour. Your eyes also have melanin-producing cells and can develop melanoma. Ocular melanoma is also known as uveal melanoma. The uvea is the middle layer of the eye beneath the white part and consists of the iris, ciliary body and choroid. Melanoma can occur any of these parts. It can also be named according to the part of the eye it started in.

Melanomas that develop on the skin usually occur on parts of the body that have been exposed to the sun. Some melanomas, however, can also start inside the eye or in a part of the body that has never been exposed to the sun.

Ocular melanoma is much rarer than skin melanoma and behaves very differently. Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, so that each new cell replaces one lost. Sometimes, however, cells become abnormal and keep growing. In cancers such as ocular melanoma, the abnormal cells form a mass called a tumour. Cancerous tumours, also known as malignant tumours, have the potential to spread to other parts of the body through the blood stream or lymph vessels and form another tumour at a new site. This is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

Most ocular melanomas develop in the part of the eye that you can’t see when looking in a mirror, so this makes ocular melanoma hard to diagnose. Ocular melanoma usually develops in any of the following three areas of the eye:

- the iris – the coloured part of the eye which helps regulate the amount of light entering the eye

- the ciliary body – the part of the eye that controls the shape of the lens and makes the fluid in the eye called aqueous humour, which provides nutrition and maintains pressure in the eye

- the choroid or posterior uvea – the vascular layer of the eye between the retina and the white outer layer (sclera).

These three areas are known as the uvea, hence the term uveal melanoma. Ocular (uveal) melanoma can occur in any of these areas, but it is more common in the choroid.

How common is ocular (uveal) melanoma?

Ocular (uveal) melanoma is rare. Each year, around 125–150 Australians are diagnosed with this type of cancer (about 5–6 cases per million people).1 It is more likely to be diagnosed in men than women, and can occur at any age, but the risk increases with age.

What are the risk factors?

The cause of ocular melanoma is not known in most cases. However, there are several risk factors including:

- having pale or fair skin. People whose skin burns easily are most at risk.

- having a light eye colour. People with blue or green eyes have a greater risk than people with darker eyes.

- family history of melanoma. A very small number of people who have melanoma have inherited a faulty gene.

- having a growth on or in the eye. People with an “eye freckle” may be at risk.

- age. The risk increases with age.

- certain skin conditions and pigmentation. Some people have a skin disorder (dysplastic naevus syndrome) which causes moles to grow abnormally, and this can increase your risk.

What are the symptoms?

Ocular melanoma can be difficult to diagnose as it forms in the part of the eye that isn’t visible to you or others. It doesn’t typically cause any signs and symptoms and is usually detected by an optometrist during a routine eye test.

Symptoms that some people may experience include:

- poor or blurred vision in one eye

- loss of peripheral vision

- brown or dark patches on the white of the eye

- a dark spot on the iris

- small specks, wavy lines or ‘floaters’ in your vision

- flashes in your vision

- a change in the shape of the pupil.

These symptoms can be caused by other eye conditions, but if you experience any of these symptoms you need to discuss them with your doctor.

How is ocular melanoma diagnosed?

If your doctor or optometrist thinks that you may have ocular melanoma, they will carry out certain tests.

If the results suggest that you may have ocular melanoma, your doctor will refer you to a specialist doctor called an ophthalmologist who specialises in treating eye disorders. The ophthalmologist will carry out more tests that may include those below.

Ophthalmoscopy (funduscopy)

Ophthalmoscopy (funduscopy) is a test that allows your doctor to look at the inside of your eye to check for abnormalities. You may be asked to look into a large microscope that sits on a table (a slit lamp examination). The doctor may put eye drops in your eye to widen (dilate) your pupil. This will allow the doctor to see inside your eye, so they may not have to perform a biopsy to determine if a tumour is present. The eye drops make your eyesight blurry for a few hours and you might find bright light uncomfortable, so take sunglasses to your appointment. You cannot drive until your eyesight returns to normal.

Colour fundus photography

Colour fundus photography takes photographs of the back of your eye (fundus) and can help show what the tumour looks like before and after treatment. The doctor will put eye drops in your eye to widen (dilate) your pupil and then use a special camera to take pictures of the fundus.

Ultrasound scan

An ultrasound scan uses soundwaves to create pictures of the inside of your eye and surrounding areas. For this scan a gel will be spread over your closed eyelid and a small device called a transducer is moved over the area. The transducer sends out soundwaves that echo when they come across something dense, like an organ or tumour. The ultrasound images are then projected onto a computer screen. An ultrasound is painless, takes only a few minutes and accurately shows the size of the tumour.

Transillumination

If you need surgery, transillumination may be done first to show exactly where the melanoma is. The lights in the room are turned down and the doctor shines a very bright light into your eye to look for abnormal areas.

CT (computerised tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans

Special machines are used to scan and create pictures of the inside of your body and are used to find tumours or to check for any spread of disease. Before the scan you may have an injection of dye (called contrast) into one of your veins, which makes the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table. For a CT scan the table moves in and out of the scanner which is large and round like a doughnut; the scan itself takes about 10 minutes. For an MRI scan the table slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends; the scan takes a little longer, about 30–90 minutes to perform and the machine is noisy so you will be given earplugs to wear. Both scans are painless.

Biopsy

Most of the time, the ophthalmologist can make a diagnosis from what they can see when they examine your eye, from photographs and ultrasound pictures. However, sometimes a biopsy is performed. In a biopsy, some tissue is removed from the affected area so it can be examined more closely under a microscope.

Finding a specialist

Rare Cancers Australia have a directory of health professionals and cancer services across Australia.

How is ocular melanoma treated?

You will be cared for by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of health professionals during your treatment for ocular melanoma.

The team may include an ophthalmologist, radiation oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of radiation therapy), medical oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of systemic therapy which includes immunotherapy), nurses and allied health professionals such as a psychologist or counsellor, a social worker, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Discussion with your doctor will help you decide on the best treatment for your cancer depending on:

- the site of the cancer you have (choroid, ciliary body or iris)

- size of the cancer

- how close the cancer is to other parts of the eye

- whether or not the cancer has spread

- your age, fitness and general health

- your preferences.

The main factors in deciding on what treatment you will have are the location and size of the tumour and wanting to save the sight of your eye. Preserving how your eye looks is also important. Treatments may include surgery, radiation therapy, laser treatment (transpupillary thermotherapy), photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy. These can be given alone or in combination.

Surgery

Surgery for ocular melanoma may involve removing just the tumour, removing part of the eye, or removing the entire eye (enucleation) if it has been severely damaged by the tumour. These operations are done while you are under a general anaesthetic and you will have to stay in hospital for one or two days.

Surgical procedures for ocular melanoma

Iridectomy - Removal of part of the iris (coloured part of the eye)

Iridocyclectomy - Removal of part of the iris and the ciliary body

Endoresection or transscleral resection - Removal of only the tumour in the ciliary body or choroid

Enucleation - Removal of the entire eye. This is performed for larger melanomas or if the vision in the eye has already been lost. An artificial eye matching your eye size and colour will usually be inserted after surgery to replace the eye

Orbital exenteration - Removal of the eye and some surrounding tissue

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses high energy rays to destroy cancer cells. It may be used for ocular melanoma:

- after surgery, to destroy any remaining cancer cells and stop the cancer coming back

- if the cancer can’t be removed with surgery

- instead of removing the eye (enucleation)

- if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. palliative radiation to control symptoms).

For ocular melanoma it is given the following ways:

Plaque radiation therapy (plaque brachytherapy) – small seeds of radioactive material are placed in a small disc (called a plaque) and attached to the wall of the eye over the tumour during an operation. Radiation is then delivered to the tumour. The plaque is left in place until the right amount of radiation has been given. This is usually about four to five days and you will have to stay in hospital during this time. After this, you will have another short operation to remove the plaque.

Proton beam radiation therapy – proton beams are aimed directly at the tumour and may cause less damage to the other tissues they pass through. Treatment is given in high doses over several days. This treatment is currently not available in Australia but check with your radiation oncologist.

Stereotactic radiation therapy – multiple small beams of radiation are used to precisely target the tumour in high doses. You usually need five sessions given over ten days.

A course of stereotactic radiation therapy needs to be carefully planned. During your first appointment you will meet with a radiation oncologist. At this planning session you will lie on an examination table and have a CT scan in the same position you will be placed in for treatment. Specific equipment, such as a frame to immobilise your head and a light to focus your gaze on, will be used to ensure your eye does not move during treatment. The information from this session will be used by your specialist to work out the treatment area, the type of radiation and how to deliver the right dose. Radiation therapists will then deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan.

Radiation therapy does not hurt and is usually given over a period of time to minimise side effects. If you need plaque brachytherapy the ophthalmologist will plan this treatment with you.

Other treatments

Other types of treatment for ocular melanoma are:

Laser treatment (transpupillary thermotherapy) or photodynamic therapy

This treatment uses an infrared laser to heat and destroy cancer cells. It is sometimes combined with photodynamic therapy which uses a laser combined with a light-sensitive drug to destroy cancer cells. The drug is injected into your vein and makes the cells in your body more sensitive to light. The treatment is painless, but you will be sensitive to light for several days after treatment.

Immunotherapy

If the ocular melanoma has spread (metastasised) to other parts of the body, immunotherapy may be considered. This treatment has been very helpful in treating metastatic skin melanoma and uses drugs to stimulate your own immune system to recognise and attack cancer cells.

Clinical trials

Your doctor or nurse may suggest you take part in a clinical trial. Doctors run clinical trials to test new or modified treatments and ways of diagnosing disease to see if they are better than current methods. For example, if you join a randomised trial for a new treatment, you will be chosen at random to receive either the best existing treatment or the modified new treatment. Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

You may find it helpful to talk to your specialist, clinical trials nurse or GP, or to get a second opinion. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time.

For more information, visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Clinical Trials and Research’

Complementary therapies

Complementary therapies are designed to be used alongside conventional medical treatments (such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) and can increase your sense of control, decrease stress and anxiety, and improve your mood.

Some Australian cancer centres have developed “integrative oncology” services where evidence-based complementary therapies are combined with conventional treatments to create patient-centred cancer care that aims to improve both wellbeing and clinical outcomes.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Some complementary therapies and their clinically proven benefits are listed below:

acupuncture – reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; improves quality of life

aromatherapy – improves sleep and quality of life

art therapy, music therapy – reduce anxiety and stress; manage fatigue; aid expression of feelings

counselling, support groups – help reduce distress, anxiety and depression; improve quality of life

hypnotherapy – reduces pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting

massage – improves quality of life; reduces anxiety, depression, pain and nausea

meditation, relaxation, mindfulness – reduce stress and anxiety; improve coping and quality of life

qi gong – reduces anxiety and fatigue; improves quality of life

spiritual practices – help reduce stress; instil peace; improve ability to manage challenges

tai chi – reduces anxiety and stress; improves strength, flexibility and quality of life

yoga – reduces anxiety and stress; improves general wellbeing and quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Alternative therapies are therapies used instead of conventional medical treatments. These are unlikely to be scientifically tested and may prevent successful treatment of the cancer. Cancer Council does not recommend the use of alternative therapies as a cancer treatment.

Nutrition and exercise

If you have been diagnosed with ocular melanoma, both the cancer and treatment will place extra demands on your body. Research suggests that eating well and exercising can benefit people during and after cancer treatment.

Eating well and being physically active can help you cope with some of the common side effects of cancer treatment, speed up recovery and improve quality of life by giving you more energy, keeping your muscles strong, helping you maintain a healthy weight and boosting your mood.

You can discuss individual nutrition and exercise plans with health professionals such as dietitians, exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Exercise for People Living with Cancer’

Side effects of treatment

All treatments can have side effects. The type of side effects that you may have will depend on the type of treatment you have. Some people have very few side effects and others have more. Your specialist team will discuss all possible side effects, both short and long-term (including those that have a late effect and may not start immediately), with you before your treatment begins.

Common side effects

Surgery - Loss of vision, damage to nearby tissue, pain, bleeding, blood clots, infection after surgery, change in appearance.

Radiation therapy - Blurry vision, dry eye, cataracts, glaucoma, loss of vision, eye discomfort, fatigue.

Laser therapy - Loss of vision, eye discomfort, bleeding inside the eye.

Immunotherapy - Infection, fatigue, skin reactions, headaches, inflammation of the heart, inflammation of the colon, inflammation of the liver, kidney problems.

Life after treatment

Once your treatment has finished, you will have regular check-ups to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back.

Ongoing surveillance for ocular melanoma involves a schedule of tests and scans, eye tests and physical examinations. Let your doctor know of any health problems between visits.

Some cancer centres work with patients to develop a “survivorship care plan” which includes a summary of your treatment, sets out a schedule for follow-up care, lists any symptoms and long-term side effects to watch out for, identifies any medical or emotional problems that may develop and suggests ways to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Maintaining a healthy body weight, eating well and being active are all important. If you don’t have a care plan, ask your specialist for one and make sure a copy is given to your GP and other health care providers.

If the cancer comes back

For some people ocular melanoma does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. If the cancer does come back, treatment will depend on where the cancer has returned in your body and may include a mix of surgery, radiation therapy, laser and immunotherapy. Enrolling in a clinical trial may also be recommended for you. In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment. Palliative care can be provided in the home, in a hospital, in a palliative care unit or hospice, or in a residential aged care facility.

When cancer is no longer responding to active treatment, it can be difficult to think about how and where you want to be cared for towards the end of life. But it’s essential to talk about what you want with your family and health professionals, so they know what is important to you. Your palliative care team can support you in having these conversations.