The bones

A typical healthy person has over 200 bones, which:

- support and protect internal organs

- are attached to muscles to allow movement

- contain bone marrow, which makes and stores new blood cells

- store nutrients, such as calcium.

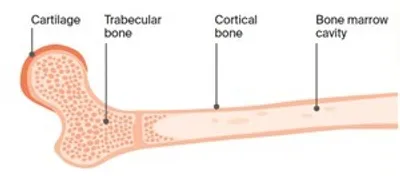

Bone structure

Bones are made up of different parts, including a hard outer layer (known as cortical bone) and an inner core (known as trabecular bone). The bone marrow is found in this inner core. Cartilage is the tough material at the end of each bone that allows one bone to move against another at a joint.

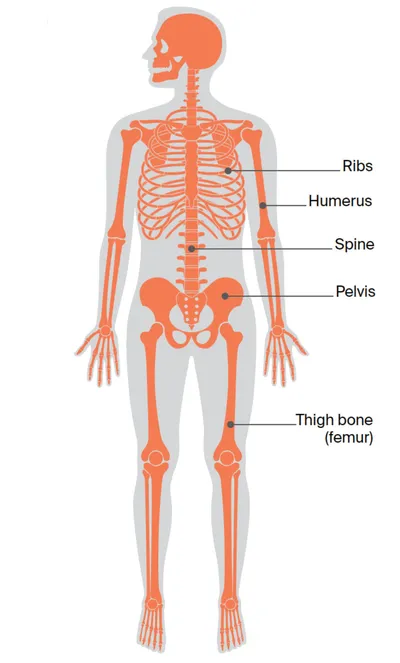

Bones of the body

Bones commonly affected by primary bone cancer include the spine, ribs, pelvis and upper bones of the arms (humerus) and legs (femur).

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about primary bone cancer are below.

What is bone cancer?

Bone cancer can start as either a primary or secondary cancer. The 2 types are different and this information is only about primary bone cancer.

Primary bone cancer – This means that the cancer starts in a bone. It may develop on the surface, in the outer layer or from the centre of the bone. As a tumour grows, cancer cells multiply and destroy the bone. If left untreated, primary bone cancer can spread to other parts of the body.

Secondary (metastatic) bone cancer – This means that the cancer started in another part of the body (e.g. breast, lung) and has spread to the bone.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Secondary Bone Cancer’

How common is bone cancer?

Primary bone cancer is rare. About 270 Australians are diagnosed with primary bone cancer each year.

It affects people of all ages, but most often occurs in people aged 10–25 and over 50.

Types of primary bone cancer

There are more than 30 types of primary bone cancer. The most common types are:

Osteosarcoma (about 35% of bone cancers)

- starts in cells that grow bone tissue

- often affects the arms, legs or pelvis, but may occur in any bone

- occurs most often in teenagers with growing bones, and older people in their 70s and 80s

- most are high-grade tumours.

Chondrosarcoma (about 30% of bone cancers)

- starts in cells that grow cartilage

- often affects the bones in the upper arms and legs, pelvis, ribs or shoulder blades

- most often occurs in adults aged over 40

- slow growing; rare types can spread to other parts of the body

- most are low-grade tumours.

Ewing sarcoma (about 15% of bone cancers)

- affects cells in the bone or soft tissue that multiply rapidly

- often affects the pelvis, legs, ribs, spine or upper arms

- most common in children and young adults

- are high-grade tumours.

Cancer that affects the soft tissues around the bones is known as soft tissue sarcoma, and may be treated differently.

What are the risk factors?

The causes of most bone cancers are unknown, but factors that may increase the risk include:

Previous radiation exposure including radiation therapy (radiotherapy) – Radiation therapy to treat cancer increases the risk of developing bone cancer. The risk is higher when high doses of radiation therapy have been given in childhood. Most people who have radiation therapy will not develop bone cancer.

Chemotherapy for another cancer – Some drugs may increase the risk of osteosarcoma.

Genetic factors – Some inherited conditions, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, increase the risk of bone cancer. People with a strong family history of certain types of cancer are also at risk. Ask for a referral to a family cancer clinic for more information. Some people develop bone cancer because of gene changes that happen during their lifetime, rather than inheriting a faulty gene.

Other bone conditions – Some people who have benign bone conditions, such as Paget’s disease of the bone, are at higher risk.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom is pain in the affected bone or joint that doesn’t improve with mild pain medicines such as paracetamol. You might have this pain most of the time, and it may be worse at night or during activity.

Other symptoms can include:

- swelling over the affected part of the bone

- stiffness or tenderness in the bone

- problems moving around (e.g. walking with a limp)

- loss of feeling in the affected arm or leg (limb)

- bone that breaks for no reason.

These symptoms do not necessarily mean you have primary bone cancer. If your symptoms last longer than 2 weeks, you should see your doctor.

How is primary bone cancer diagnosed?

If you have symptoms, your doctor will ask about your medical history and do a physical examination.

It is likely that you will have some of the following tests:

- x-rays – can show bone damage or whether new bone is growing

- blood tests – help check your overall health

- CT and/or MRI scans – create pictures to highlight any bone abnormality

- specialised scans – highlight any cancerous areas in the body with a small amount of radioactive solution that is injected before a scan to, e.g. PET, thallium or technetium scans

- bone biopsy – collects some cells and tissues from the outer part of the affected bone. The biopsy may be done in one of two ways. In a core biopsy, a local anaesthetic is used to numb the area, then a sample is taken using a needle. A CT or ultrasound scan is used to guide the needle into place. For an open biopsy, you have a general anaesthetic, then the surgeon makes a cut in the skin to remove a piece of bone. The sample is tested for cancer cells and checked for gene changes

- bone marrow biopsy – a thin needle is used to remove a sample of marrow from the hip bone.

Selecting the bone site to biopsy

A bone biopsy is a specialised test. It is best to have the biopsy at the specialist treatment centre where you would be treated if it is cancer. The specialists will usually work together to decide the best site to place the needle. The site to biopsy must be carefully chosen so it doesn’t cause problems if further surgery is needed. This also helps ensure the sample is useful and reduces the risk of the cancer spreading.

Staging

The test results will help show where the cancer is and if it has spread. This is called staging. Knowing the stage helps your doctors plan your treatment.

Grades of primary bone cancer

Grading describes how quickly a cancer might grow. In general, the lower the grade, the better the outlook.

Low grade – The cancer cells look like normal cells. They usually grow slowly and are less likely to spread.

High grade – The cancer cells look very abnormal. They grow quickly and are more likely to spread.

Stages of primary bone cancer

Many cancers are staged using a system that divides them into 4 stages, but bone cancer is different. It is usually divided into localised or advanced. Ask your doctor to explain the stage of cancer to you.

Localised – The cancer contains low-grade cells and is found in the bone in which it started. It can be removed by surgery (resectable) or not removed completely (non-resectable).

Advanced (metastatic) – The cancer is any grade and has spread to other parts of the body (e.g. the lungs).

Treatment for primary bone cancer

The treatment of bone cancer is complex and requires specialist care.

Research shows that having treatment at a specialist treatment centre means better recovery and longer survival. Treatment will depend on:

- the type of primary bone cancer

- the location and size of the tumour

- whether or not the cancer has spread

- your age, fitness and general health.

Primary bone cancer is usually treated by surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or a combination of those. The aim is to control the cancer and maintain the use of the affected area of the body. Many people who are treated for bone cancer go into complete remission (when there is no evidence of active cancer).

Specialist sarcoma treatment centres

You can find specialised sarcoma treatment centres at certain hospitals and cancer centres in major cities throughout Australia.

These specialist centres have multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) who regularly manage this cancer. The team will include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, radiologists and clinical nurse consultants. It will also include allied health professionals such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and social workers. Some centres also have oncologists with experience in treating children and young people with bone cancer.

To find a specialised sarcoma team in your state or territory, visit the Australia and New Zealand Sarcoma Association. You might have to travel for treatment.

Preparing for treatment

Ask about fertility – Treatment may affect your ability to conceive a child (fertility). Before treatment starts, you may be able to store sperm, eggs, embryos or ovarian tissue.

Avoiding fractures – If your doctor thinks you may be at risk of a bone fracture, they may recommend you wear a splint to support the bone or use crutches.

Checking heart and kidneys – Your doctor may recommend you have some tests to check how well your heart and kidneys are working, as some types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy may affect these organs.

Surgery

The type of operation you have will depend on where the cancer is in the body.

Limb-sparing surgery

Surgery to remove the cancer but save (salvage) the arm or leg (limb) can be done in most people. You will have a general anaesthetic, and the surgeon will remove the affected part of the bone. The surgeon will also take out some surrounding normal-looking bone and muscle with a layer of surrounding normal tissue. This is called a wide local excision, and it reduces the chance of the cancer coming back. A pathologist checks the tissue to see whether the edges are clear of cancer cells.

The bone that is removed is usually replaced with a metal implant or a bone graft. A graft uses healthy bone from another part of your body or from a “bone bank”. A bone bank is a facility that collects tissue for research and surgery. In some cases, the removed bone is treated with radiation therapy to destroy the cancer cells, then used to reconstruct the limb.

After surgery, you will be given medicine to manage pain and reduce the chance of getting an infection in the bone or metal implant. There are likely to be some changes in the way the limb looks, feels or works.

A physiotherapist can show you exercises to help you regain strength and improve how the limb works.

Surgery to remove the limb (amputation)

For about 1 in 10 people, the only way to remove the cancer completely is to remove the limb (amputation). This procedure is less common now because techniques used for limb-sparing surgery have improved. However, amputation may be needed in certain situations.

After surgery, you will be given medicine to manage the pain and taught how to care for the stump that remains (residual limb). After the area has healed, you may be fitted for an artificial limb (prosthesis).

If you have an arm removed, an occupational therapist will teach you how to eat and dress yourself using one arm. If you receive a prosthetic arm, the occupational therapist will teach you exercises and techniques to control and use the prosthesis.

If you have a leg removed and receive a prosthesis, a physiotherapist will show you exercises and techniques to improve how you walk and move with your new limb. Some people choose to use a wheelchair instead of a prosthetic leg.

Surgery in other parts of the body

Pelvis – When possible, the cancer is removed along with some healthy tissue around it (wide local excision). Some people may need to have a bone graft or a metal implant to rebuild the bone.

Jaw or cheek bone (mandible or maxilla) – The surgeon will remove the affected bone. Bone from other parts of the body may be used to replace the affected bone. As the face is a delicate area, it may be difficult to remove the cancer with surgery, and some people may need to have chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Spine or skull – If surgery isn’t possible, a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be used. If you need one of these treatments, your doctor will explain what will happen.

Chemotherapy

This treatment uses drugs to destroy or slow the growth of cancer cells, while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells. It may be given for high-grade osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma:

- before surgery, to shrink the size of the tumour and make it easier to remove

- after surgery or radiation therapy, to kill any cancer cells possibly left behind

- as palliative treatment, to help stop the growth of an advanced cancer or control the symptoms.

Chemotherapy drugs are often injected into a vein. This may be as a day patient, or during a hospital stay. You will need scans (MRI, CT or PET–CT) during treatment to see how well the cancer is responding to the chemotherapy.

Side effects – These depend on the drugs that are given and where the cancer is in your body. Common side effects include fatigue (tiredness), nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, hair loss, constipation, diarrhoea, numbness or tingling in the hands and feet, effects on hearing and increased risk of infection. Talk to your treatment team about ways to manage side effects. If your red blood cell count drops too low, you may need a transfusion to build them up again.

Radiation therapy

This treatment uses targeted radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is usually in the form of x-ray beams. Radiation therapy may be used for Ewing sarcoma:

- after surgery or chemotherapy, to kill any cancer cells possibly left behind

- as an alternative treatment to surgery if a wide local excision is not possible

- as palliative treatment, to help stop the growth of an advanced cancer or control the symptoms.

Radiation therapy is usually given every weekday, with a rest over the weekend, for several weeks. Your specialist will provide details about your specific treatment plan.

Side effects – These will depend on the area being treated and the strength of the dose you have. Common side effects include fatigue (tiredness), skin redness or soreness, and hair loss in the treatment area. Ask your treatment team for advice about dealing with any side effects.

Should I join a clinical trial?

Over the years, clinical trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

Talk with your doctor about the latest clinical trials and whether you’re a suitable candidate. For more information, visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Download our booklet Understanding Clinical Trials and Research’

Coping with primary bone cancer

Being diagnosed with a rare cancer can be distressing.

The physical changes after treatment for bone cancer can affect how you feel about yourself (self-esteem) and make you feel self-conscious. It will take time to get used to the differences in how you look and what you can do.

Limb-sparing surgery is a major operation that can leave a scar and make the skin feel tight. If you have an amputation or a lot of bone is removed, you may feel grief and loss. Many people find it helps to talk to a counsellor, psychologist, friend or family member. Ask your treating team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to find out about support services in your area.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment, you will need regular check-ups for several years to confirm that the cancer hasn’t come back and to help you manage any treatment side effects.

How often you will need to see your doctor will vary depending on the type of bone cancer. Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Let your doctor know immediately of any health concerns between appointments.

If the cancer comes back

For some people, bone cancer does come back (recur) after treatment. The risk that bone cancer will recur is greater within the first 3 years after treatment has finished. Treatment options may include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

In some cases of advanced primary bone cancer, treatment will focus on managing your symptoms and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. Palliative treatment can relieve pain and help to manage other symptoms.

Question checklist

This checklist may be helpful when thinking about questions to ask your doctor.

- What type of bone cancer do I have?

- What treatment do you recommend and why?

- How can I find a specialist treatment centre?

- What is the prognosis?

- If I have surgery, what are the side effects?

- Do I need an amputation?

- If I have to travel for treatment, is there any government funding available to help with the cost?

- Are there any clinical trials I could join?

- If the cancer has spread outside the bone, what treatment options are available for me?

- How often will I need check-ups after treatment?

- If the cancer comes back, how will I know?