What is a tumour?

A tumour is an abnormal growth of cells. Cells are the body’s building blocks – they make up tissues and organs. The body constantly makes new cells to help us grow, replace worn-out tissue and heal injuries.

Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, so that each new cell replaces one lost. Sometimes, however, cells become abnormal and keep growing. In solid cancers, such as a brain tumour, the abnormal cells form a mass or lump called a tumour.

How are brain tumours classified?

Brain tumours are often classified as benign or malignant. What it means to have a benign or malignant brain tumour is usually different to what it may mean to have one in another part of the body.

Benign tumours

Many benign brain tumours grow slowly and are less likely to spread or grow back (if all of the tumour can be successfully removed). But a benign tumour may still affect how the brain works. This can be life-threatening and need urgent treatment. Sometimes a benign tumour can change over time and become malignant or more aggressive.

Malignant tumours

A malignant brain tumour may be called brain cancer. Some malignant brain tumours can grow relatively slowly, while others grow rapidly. They are considered life-threatening because they may grow larger, spread within the brain or to the spinal cord, or come back after initial treatment.

Primary cancer

A cancer that starts in the brain is called primary brain cancer. It may spread to other parts of the nervous system. Unlike other malignant tumours that have the potential to spread throughout the body, primary brain cancers usually do not spread outside the brain and spinal cord.

Secondary cancer

Sometimes cancer starts in another part of the body and then travels through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to the brain. This is known as a secondary cancer or metastasis. The cancers most likely to spread to the brain are melanoma, lung, breast, kidney and bowel. A metastasis keeps the name of the original cancer. For example, bowel cancer that has spread to the brain is still called metastatic bowel cancer, even though the person may be having symptoms because cancer is in the brain.

The brain and spinal cord

The brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system (CNS). This CNS controls how the mind and body works.

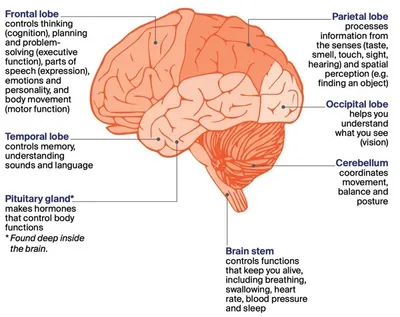

The brain – The brain receives and interprets information carried to it by nerves from the sensory organs that control taste, smell, touch, sight and hearing. It also sends messages through nerves to the muscles and organs. The brain controls arm and leg movement and sensations, memory and other thinking skills, personality and behaviour, and balance and coordination. The main parts of the brain are the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brain stem.

Spinal cord – The spinal cord extends from the brain stem to the lower back. It is made up of nerve tissue that connects the brain to all parts of the body through a network of nerves called the peripheral nervous system. The spinal cord lies in the spinal canal, protected by a series of bones (vertebrae) called the spinal column.

Meninges – These are thin layers of protective tissue (membranes) that cover both the brain and spinal cord.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – Found inside the skull and spinal column, CSF surrounds the brain and spinal cord and protects them from injury.

Pituitary gland – Found at the base of the brain, the pituitary gland is about the size of a pea. It makes chemical messengers (hormones) and releases them into the blood. These hormones control many body functions, including growth, fertility, metabolism and development.

The central nervous system

The parts of the brain and their functions

The largest part of the brain is the cerebrum. It is divided into two halves called hemispheres. Each hemisphere is divided into four main areas – the frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal lobes.

- Left cerebral hemisphere – controls right side of the body and speech (for most people)

- Right cerebral hemisphere – controls left side of the body

- Corpus callosum – a thick band of nerve fibres that connects the left and right hemispheres and transfers information between them

The other main parts of the brain are the cerebellum and the brain stem. The cerebellum is found at the back of the head. The brain stem connects the brain to the spinal cord. Each part of the brain controls different bodily functions.

- Frontal lobe – controls thinking (cognition), planning and problem-solving (executive function), parts of speech (expression), emotions and personality, and body movement (motor function)

- Temporal lobe – controls memory, understanding sounds and language

- Pituitary gland – makes hormones that control body functions * Found deep inside the brain

- Parietal lobe – processes information from the senses (taste, smell, touch, sight, hearing) and spatial

perception (e.g. finding an object) - Occipital lobe – helps you understand what you see (vision)

- Cerebellum – coordinates movement, balance and posture

- Brain stem – controls functions that keep you alive, including breathing, swallowing, heart rate, blood pressure and sleep

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about brain and spinal cord tumours are below.

What is a brain or spinal cord tumour?

A brain or spinal cord tumour starts when abnormal cells grow and form a mass or lump. The tumour may be benign or malignant, but both types can be serious and may need urgent treatment. Brain and spinal cord tumours are also called central nervous system or CNS tumours.

How common are they?

Every year an estimated 1900 malignant brain tumours are diagnosed in Australia. They are more common in men than women. Malignant brain tumours can affect people of any age. About 110 children (aged 0–14) are diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour each year.

Benign brain and spinal cord tumours are more common than malignant tumours. The risk of being diagnosed with a brain tumour increases with age.

What types of tumours are there?

The brain is made up of different types of tissues and cells, which can develop into different types of tumours. There are more than 40 main types of primary brain and spinal cord tumours. They can start in any part of the brain or spinal cord. Tumours are grouped together based on the type of cell they start in and how the cells are likely to behave (based on their genetic make-up). These groups include glioma and non-glioma tumours. Gliomas are the most common type of malignant brain tumour.

Common types of primary brain tumours

Glioma tumours

These tumours start in the glial (neuroglia) cells of the brain.

Astrocytoma – starts in glial cells called astrocytes; may be benign or malignant

Glioblastoma – type of malignant astrocytoma; may develop from a slow-growing astrocytoma; makes up more than half of all gliomas; common in both adults and children

Oligodendroglioma – starts in glial cells called oligodendrocytes; more common in younger adults; malignant, but may be slow or fast growing

Ependymoma – starts in glial cells called ependymal cells; more common in children than adults; may be benign or malignant.

Non-glioma tumours

These tumours start in other types of cells found in the brain.

Meningioma – starts in the membranes (meninges) covering the brain and spinal cord; most common primary brain tumour, usually benign and slow growing

Medulloblastoma – starts in the cerebellum; malignant tumour; more common in children; rare in adults

Pituitary tumour – starts in the pituitary gland; usually benign

Schwannoma – starts in Schwann cells, which surround nerves in the brain and spinal cord; usually benign; includes vestibular schwannomas (sometimes called acoustic neuromas)

What are the risk factors?

The cause of most brain and spinal cord tumours is unknown. As we get older the risk of developing many cancers, including brain cancer, increases. Other things known to increase a person’s risk include:

Family history – It’s rare for brain tumours to run in families, though some people inherit a gene change from their parent that increases their risk. For example, a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis can lead to mostly benign tumours of the brain and spinal cord. Having a parent, sibling or child with a primary brain tumour may sometimes mean an increase in risk.

Radiation therapy – People who have had radiation therapy to the head, particularly for childhood leukaemia, may have a slightly higher risk of brain tumours, such as meningioma, many years later.

Chemical exposure – A chemical called vinyl chloride, some pesticides, and working in rubber manufacturing and petroleum refining have been linked with brain tumours.

Overweight and obesity – A small number of meningioma brain tumours are thought to be linked to high body weight or obesity.

Mobile phones and microwave ovens

Research has not shown that mobile phone use causes brain cancer, but studies continue into any long-term effects. If you are worried, use a hands-free headset, limit time on your phone, or use messaging. There is no evidence that microwave ovens in good condition release electromagnetic radiation at levels that are harmful to people.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms you may experience depend on where the tumour is, its size and how slowly or quickly it is growing. Symptoms can develop suddenly (in days or weeks) or over time (months or years). Many symptoms are the same as other conditions, but see your doctor about any new, persistent or worsening symptoms.

Brain tumours can increase pressure inside the skull (intracranial pressure). Pressure can build up because the tumour is taking up too much space, is causing brain swelling or is blocking the flow of cerebrospinal fluid around the brain. This increased pressure can lead to symptoms such as:

- headaches – often worse when you wake up

- nausea and vomiting – often worse in the morning or after changing position (e.g. moving from sitting to standing)

- confusion and irritability

- blurred or double vision

- seizures (fits) – might cause some jerking or twitching of your hands, arms or legs, or affect the whole body

- weakness in parts of the body

- poor coordination

- drowsiness or loss of consciousness

- difficulty speaking or finding the right words.

Common tumour symptoms

The symptoms you experience will depend on where the tumour is in the brain or spinal cord.

Frontal lobe

- difficulty with planning or organising activities

- changes in behaviour, personality and social skills

- depression or mood swings

- weakness in part of the face, or on one side of the body

- difficulty walking

- loss of sense of smell

- problems with seeing or speaking

- trouble finding the right word

Temporal lobe

- forgetting events and conversations

- difficulty understanding what is said to you or recognising sounds

- trouble learning and remembering new information

- seizures with strange feelings, smells or Deja Vu

Pituitary gland

- headaches

- loss of vision (often side or peripheral vision)

- nausea or vomiting

- erection problems

- less interest in sex

- thyroid and other hormone changes

Parietal lobe

- problems with reading or writing

- loss of feeling in part of the body

- difficulty telling left from right

- difficulty locating objects around you

Occipital lobe

- loss of all or some vision

Meninges

- headaches

- vomiting

- weakness in the arms or legs

- personality changes or confusion

Cerebellum

- coordination and balance problems

- uncontrolled eye movement

- stiff neck

- dizziness

- difficulty speaking (staccato speech)

Spinal cord

- back and neck pain

- numbness or tingling in the arms or legs

- change to muscle tone in the arms or legs

- clumsiness or difficulty walking

- loss of bowel or bladder control (incontinence)

- change in the feeling in the genital or anal area or erection problems

Nerve and other tumours

Symptoms of tumours starting in the brain’s nerves (cranial nerves) depend on the affected nerve. The most common nerve tumours are vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas). They can cause hearing loss, dizziness and balance issues. Vestibular schwannomas are usually benign. Tumours of the pineal gland (deep within the brain) are very rare and usually classified as neuroendocrine tumours.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your general practitioner (GP) or another doctor will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out a tumour, you will usually be referred to a specialist, such as a neurosurgeon or neurologist. The specialist will examine you and arrange further tests.

If a tumour is diagnosed, the specialist will consider your treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Health professionals you may see

Neurosurgeon – diagnoses and surgically treats diseases and injuries of the brain and nervous system

Neurologist – diagnoses and treats diseases of the brain and nervous system, particularly those not requiring surgery; helps manage thinking and memory changes and seizures

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiation therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy and targeted therapy (systemic treatment)

Cancer care coordinator, patient navigator – coordinate your care, liaise with other members of the MDT and support you and your family throughout treatment; a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS) may also coordinate your care

Nurse – administers medicines and drug therapies; provides care, information and support

throughout treatment

Pathologist, neuropathologist – analyse blood and tissue from the brain and spinal cord

Rehabilitation specialist – recommends and oversees treatment to help you recover movement, mobility and speech after treatment and return to your usual activities

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Neuropsychologist – assesses people who have problems in thinking or behaviour caused by illness or injury (particularly to the brain) and manages their rehabilitation

Psychologist, psychiatrist – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Physiotherapist, occupational therapist – assist with physical and practical problems, including restoring movement and mobility after treatment, and recommending aids, devices and equipment

Speech pathologist, speech therapist – help with communication, swallowing and speech

after treatment

Exercise physiologist – prescribes safe and effective exercise to help people with medical conditions restore or improve their overall health, fitness, strength and energy levels

Palliative care specialists and nurses – work closely with the GP and cancer team to help

control symptoms and maintain quality of life

How are brain and spinal cord tumours diagnosed?

The doctor will ask about your symptoms and medical history, and do a physical examination. If they suspect you may have a brain or spinal cord tumour, you will be referred for tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

Physical examination

Your doctor will assess your nervous system to check how different parts of your brain and body are working, including your speech, hearing, vision and movement. This is called a neurological examination and may include:

- checking your reflexes (e.g. knee jerks)

- testing the strength in your arm and leg muscles

- walking, to show your balance and coordination

- testing sensations (e.g. if you can feel light touch or pinpricks)

- thinking exercises, such as simple arithmetic or memory tests.

The doctor may also test your eye and pupil movements, and look into your eyes using an instrument called an ophthalmoscope. This allows the doctor to see parts of the eye and its function – including your optic nerve, which sends information from the eyes to the brain. Swelling of the optic nerve can be an early sign of raised pressure inside the skull.

Blood tests

You are likely to have blood tests to check your overall health. Most brain and spinal cord tumours cannot be found or monitored by a blood test. However, blood or special urine tests can be used to check whether the tumour is producing unusual levels of hormones, for example, if the pituitary gland is affected.

MRI scan

Your doctor will usually recommend an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to check for brain tumours and to help plan treatment. An MRI scan uses a powerful magnet and a computer to build up detailed pictures of your body. Let your doctor or nurse know if you have a pacemaker or any metallic object in your body (e.g. surgical clips after heart or bowel surgery). The magnet can interfere with some pacemakers, but newer pacemakers are often MRI-compatible.

For an MRI, you may be injected with a dye (known as contrast) that highlights any abnormalities in your brain. You will then lie on an examination table inside a large metal tube that is open at both ends.

The test is painless, but the noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you may get upset, talk to your medical team before you go for the scan. You may be given medicine to help you relax or be able to bring someone into the room for support. You will have headphones or earplugs and you can press a distress button if you are worried at any time. An MRI takes 30–45 minutes.

The pictures from an MRI scan are generally more detailed than pictures from a CT scan.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dyes or contrast during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

CT scan

Many people may have a CT (computerised tomography) scan, or it may be used if you are unable to have an MRI. This scan uses x-rays and a computer to create detailed pictures of the inside of the body.

Sometimes a dye (known as contrast) is injected into a vein before the scan to help make the pictures clearer. The contrast may make you feel hot all over and leave a bitter taste in your mouth. You may also feel like you are going to pee. These sensations usually only last a couple of minutes.

The CT scanner is a large, open doughnut-shaped machine. You will lie on a table that moves in and out of the scanner. It may take about 30 minutes to prepare for the scan, but the actual test takes only about 10 minutes and is painless.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dyes or contrast during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Further tests

You may have some of the tests listed below to find out more information about the tumour and help your doctor plan treatment.

MRS scan – An MRS (magnetic resonance spectroscopy) scan is a specialised type of MRI. It is sometimes done at the same time as a standard MRI, but is more often used to check if a tumour has grown back after treatment. An MRS scan looks for changes in the chemicals in the brain.

MR tractography – An MR (magnetic resonance) tractography scan helps show the message pathways (tracts) within the brain, e.g. the visual pathway from the eye. It may be used to help plan treatment for gliomas.

MR perfusion scan – This type of scan shows the amount of blood flowing to various parts of the brain. It can also be used to help identify more features of the tumour, or may be used after treatment.

SPET or SPECT scan – A SPET or SPECT (single photon emission computerised tomography) scan shows blood flow in the brain. You will be injected with a small amount of radioactive fluid and then your brain will be scanned with a special camera. Areas with higher blood flow, such as a tumour, will show up brighter on the scan.

PET scan – For a PET (positron emission tomography) scan, you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive solution. Cancer cells absorb the solution at a faster rate than normal cells and show up brighter on the scan.

Lumbar puncture – Also called a spinal tap, a lumbar puncture uses a needle to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal column. The fluid is checked for cancer cells in a laboratory.

Biopsy – If scans show an abnormality that looks like a tumour, some tissue may be removed and tested. During a biopsy, the neurosurgeon makes a small opening in the skull and inserts a needle to take a small sample. Or they may take a biopsy through your nose. A biopsy may also be taken during surgery, while the neurosurgeon removes as much of the tumour as possible. A specialist doctor called a pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope for signs of cancer and to work out the specific type of tumour.

Molecular testing – A pathologist will run special tests on the biopsy sample to look for specific changes in the genes of the tumour cells (called molecular markers). These gene changes may happen during a person’s life (acquired) or be passed through families (inherited). The test results can help identify the features of the tumour so your doctors can recommend the most appropriate treatment. Ask your doctor about genetic testing.

Grading tumours

The tumour will be given a grade based on how the cells look compared to normal cells. The grade suggests how quickly the cancer may grow. The grading system most commonly used for brain tumours is from the World Health Organization. Brain and spinal cord tumours are usually given a grade from 1 to 4, with 1 being the lowest grade and least aggressive, and 4 the highest grade and most aggressive.

Unlike cancers in other parts of the body that are given a stage to show how far they have spread, primary brain and spinal cord tumours are not staged, because most don’t spread to other parts of the body.

Grades of brain and spinal cord tumours

|

grade 1 |

These tumours are low grade, slow growing and benign. |

|

grade 2 |

These tumours are low grade and usually grow slowly. They are more likely to come back after treatment and can develop into a higher-grade tumour. |

|

grades 3 and 4 |

These tumours are high grade, faster growing and malignant. They can spread to other parts of the brain and tend to come back after treatment. |

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your individual prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

Several factors may affect your prognosis, including:

- the tumour type, location, grade and genetic make-up

- your age, general health and family history

- whether the tumour has damaged the surrounding healthy brain tissue

- how well the tumour responds to treatment.

Both low-grade and high-grade tumours can affect how the brain works and be life-threatening, but the prognosis may be better if the tumour is low grade, or if the surgeon is able to safely remove the entire tumour.

Some brain or spinal cord tumours, particularly gliomas, can keep growing or come back. They may also change (transform) into a higher-grade tumour. In this case, treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be used to control the growth of the tumour for as long as possible, relieve symptoms and maintain quality of life.

My wife Robyn was diagnosed with grade 4 brain cancer when she had just turned 50. After getting a diagnosis like that, you just go into shock for a couple of days, then you start thinking about how things will change, you evaluate your life and what you need to do to help.

Treatment

Treatments offered for a brain or spinal cord tumour will depend on:

- the type, size, grade, location and genetic make-up of the tumour

- your age, medical history and general state of health

- the symptoms you have

- the aim of treatment – whether to remove as much of the tumour as possible; to slow the tumour’s growth; or to relieve symptoms by shrinking the tumour and reducing swelling.

The tumour type may not be known for certain until after a biopsy or surgery. Treatment is planned by what the surgeon thinks the tumour may be from scans. For a benign tumour, surgery may be the only treatment. For a malignant tumour, treatment may include surgery, radiation therapy, and drug therapies such as chemotherapy or targeted therapy. Medicines, such as steroids or anticonvulsants, may reduce symptoms or manage seizures. You may have a new or modified treatment, such as immunotherapy, on a clinical trial.

Surgery

Brain or spinal cord surgery is called neurosurgery. Surgery may:

- remove the whole tumour (total resection)

- remove part of the tumour (partial resection or debulking)

- help diagnose a brain tumour (biopsy).

All of the tumour will be removed if it can be done safely, but this will depend on the type and location of the tumour. Removing part of the tumour may be considered when the tumour covers a wider area or is near major blood vessels or other important parts of the brain or spinal cord. This may help reduce the pressure on your brain, which will improve some of the symptoms.

When surgery is not possible

Sometimes a tumour is considered unsafe to remove because it is too close to certain parts of the brain, and surgery would cause blindness, loss of speech, paralysis or other serious complications. Sometimes these may be called inoperable or unresectable tumours. A needle

biopsy is still often possible and can help to guide treatment options. Your doctor will talk to you about what treatments you can have and ways to manage symptoms.

What to expect before surgery

The different scans used to diagnose a brain tumour (such as MRI or CT scans) are often done again to plan surgery. Some people may have a functional MRI (fMRI) to help the surgeon avoid damaging the most important areas of the brain. You will be asked to complete brain exercises during the MRI scan to show the exact areas of the brain that are used as you speak or move. These parts of the brain can also be found during surgery with brain mapping.

Tell your doctor about any blood-thinning or other medicines, and any supplements that you take. Some medicines interfere with the anaesthetic used during the operation, so you may need to stop taking them for a while. If you smoke or vape, it is important to stop before surgery, as smoking or vaping can increase the risk of complications.

Having surgery to the brain can sound frightening and it is natural to feel anxious beforehand. Talk to your treatment team about your concerns or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for support.

Types of surgery

Different types of surgery are used for brain and spinal cord tumours.

Removing a brain tumour (craniotomy) – This is the most common type of brain tumour surgery. A craniotomy removes all or part of the tumour (total or partial resection) and may be done while you are asleep under general anaesthetic.

The surgeon cuts an area of bone (called the bone flap) from your skull to access the brain and remove the tumour. The bone is then put back and a small plate is screwed on to hold the piece of skull in place.

If you have a high-grade glioma, you may drink a solution before surgery to make the tumour glow under a special blue light. This helps the surgeon remove as much of the tumour as possible, while avoiding normal brain tissue.

Brain mapping – An electrode is placed on the outside layer of the brain to stimulate and pinpoint important areas of the brain. Brain mapping may be done during surgery, or as part of an awake craniotomy.

Awake craniotomy – This operation may be recommended if the tumour is near parts of the brain that control speech or movement. You are usually put to sleep (general anaesthetic) and are later woken up but relaxed (conscious) for part of the operation. The surgeon asks you to speak or move parts of your body to identify and avoid damaging those parts of the brain.

You may be worried that an awake craniotomy will be painful, but the brain itself does not feel pain and local anaesthetic is used to numb surrounding tissues.

Removing a pituitary tumour (endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery) – The most common surgery for pituitary gland tumours (and other tumours located near the base of the brain) is called endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. To remove the tumour, the surgeon inserts a long, thin tube with a light and camera (called an endoscope) through the nose and into the skull at the base of the brain. An ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon may also assist with this type of surgery. You will be given a general anaesthetic for this operation.

Removing a spinal cord tumour (laminectomy) – The most common surgery for spinal cord tumours is a laminectomy. The surgeon makes an opening through the skin, muscle and a vertebra in the spinal column to remove the tumour. You usually have a general anaesthetic for this type of surgery.

Some spinal cord tumours may also need surgery to the spinal cord itself. Your surgeon will talk to you about this particular surgery, as it may have a risk of nerve or spinal cord injury.

Computer-assisted surgery

It is now usual for a craniotomy to be done using a computer system to guide the surgeon. This is known as stereotactic surgery.

The computer uses the results of planning scans to create three-dimensional images of the brain and tumour. During the operation, this allows the surgeon to see the scan images at particular places in the head and position the surgical instruments more precisely.

Stereotactic surgery is safer, more accurate and requires a smaller cut in the skull than non-computer assisted surgery.

What to expect after surgery

You will be closely monitored for the first 12–24 hours after the operation. For the first day or two, you will be in the intensive care or high dependency unit. You may stay in hospital for only 2 or up to 10 days. How long you stay in hospital will depend on whether you have any problems or side effects after the surgery.

Checks and observations – Nurses will regularly check your breathing, blood pressure, pulse, temperature, pupil size, and arm and leg strength and function. You will also be asked questions to assess your level of consciousness. These are called neurological observations, and help to check how your brain and body are recovering from surgery.

Spinal cord checks – If you have had an operation on your spinal cord, the nurses will regularly check the movement and sensation in your arms and legs. You may need to lie flat in bed for 2–5 days to allow the wound to heal. A physiotherapist will help you learn how to roll over and how to get out of bed safely, to avoid damaging the wound.

Pressure stockings – You will need to wear pressure stockings on your legs to prevent blood clots forming while you are recovering from surgery. Tell your doctor or nurse if you have pain or swelling in your legs or suddenly have difficulty breathing.

Bandages and bruising – The wound is covered with a dressing, which varies from a small adhesive pad to bandaging covering your head. Some or all of your head may be shaved. After some surgery, your face and eyes may be swollen or bruised. It’s not usually painful and should ease in about a week. You may have dissolvable sutures (stitches) that don’t need to be removed, they simply fall out. Or you may have sutures or staples that need to be taken out once the wound has healed. You will have a scar, and your hair won’t grow in the scar – but it’s usually behind the hairline and once the rest of your hair grows back it isn’t easily seen.

Having a shunt – Rarely, there may be a build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, called

hydrocephalus. It may be caused by the tumour or it can happen after surgery. To drain the extra fluid, you may have a temporary or permanent shunt (a long thin tube placed into your brain). For a temporary shunt (called an external ventricular drain), the tube drains fluid into a bag on the outside of the body. For a permanent shunt, the tube is inserted completely inside your body. It drains into your abdomen and the fluid is absorbed into your bloodstream.

Headaches and nausea – You may have a headache or nausea after the operation. Both can be treated with medicines.

Side effects of surgery

Infection – Although the risk is small, you may develop an infection at the wound site. This can usually be treated with antibiotics. A small number of people may need surgery to have the wound cleaned out and possibly the bone flap removed. Another surgery will usually be done later on to replace the missing area, for safety and to look natural.

Bleeding – This is a rare but serious side effect. You’ll have a CT or MRI scan the day after surgery to check for any bleeding or swelling.

Swelling – Surgery can cause swelling in the brain, which increases the pressure inside the skull (intracranial pressure). Your medical team will monitor the swelling and try to reduce it with medicines.

Other side effects – You may continue to feel confused and dizzy, have speech problems, weakness in parts of the body and seizures. You and your family or carers may be surprised that you may feel worse than before the surgery and worry that you are not recovering well. These side effects are normal and often improve with time.

Rehabilitation after surgery

Some people recover and can gradually return to their usual activities. For others, there are longer-term changes to speech, movement, behaviour and thinking. A range of therapies can help recovery or show you ways to manage any longer-term changes. These therapies are known as rehabilitation. At first, you may have some rehabilitation therapies in the hospital or a rehabilitation facility. Once you return home, you can continue rehabilitation therapies as an outpatient. You may also be given equipment to use at home. You will have other changes, such as not being able to drive for a while.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage tumour cells in the area being treated. The radiation is usually in the form of x-ray beams.

For gliomas, radiation therapy is usually given after surgery, and sometimes with chemotherapy (chemoradiation). Before you start radiation therapy, a radiation therapist will take measurements of your body and do a CT or MRI scan to work out the precise area to be treated. Treatment is carefully planned to do as little harm as possible to the healthy brain tissue near the tumour. Radiation therapy itself is painless, though you may experience some side effects. Your treatment team will discuss these with you before you begin treatment.

For high-grade glioblastomas, radiation therapy is usually combined with chemotherapy. This is called chemoradiation. The chemotherapy drugs make the cancer cells more sensitive to radiation therapy

If you are having radiation therapy for a brain tumour, you will wear a special plastic mask over your face. If you are having radiation therapy for a spinal cord tumour, some small marks may be tattooed on your skin to show the treatment area.

How often you have radiation therapy (the treatment course) will depend on the size and type of tumour. Usually it is given once a day, from Monday to Friday, for several weeks (often 3 or 6 weeks, but this varies person to person). During treatment, you will lie on a table under a machine called a linear accelerator (LINAC). Most machines use daily imaging scans to check you are in the correct position for treatment. Each treatment will last for about 10–15 minutes.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS)

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is a specialised type of radiation therapy, not a type of surgery, and no cuts are made in the skull.

A specialised radiation machine is used to give very precisely targeted radiation to the tumour. Machine types include LINAC, Gamma Knife and CyberKnife. They deliver a high dose of radiation to the tumour while the surrounding healthy brain tissue receives very little.

SRS is not suitable for all types of brain tumours. It may be offered when neurosurgery is not possible, or as an alternative. It is mostly used for cancers that have spread to the brain from another part of the body. Some meningiomas, pituitary tumours, schwannomas, and occasionally gliomas that have come back, may be treated this way.

Often, only 2 or 3 doses of SRS are needed (though you may have 1–5 doses as treatment is personalised). A treatment session may last 15–45 minutes, depending on the type of radiosurgery given. You will need to wear a special mask or frame during the treatment. You will usually be able to go home after the session ends.

Stereotactic radiation therapy (SRT)

A stereotactic radiosurgery machine may also be used to deliver a longer course of radiation, particularly for benign brain tumours. This is called stereotactic radiation therapy or SRT. The treatment is given as multiple small daily doses.

Wearing an immobilisation mask

You’ll need to wear an immobilisation mask during radiation therapy to the brain. It helps keep your head still so that the radiation is targeted at the same area during each session. The mask is made to fit you and fixed to the table when the radiation treatment is given.

The mask is made of a tight-fitting plastic mesh that you can see and breathe through. It may feel strange and confined but you usually only wear it for about 10 or 20 minutes at a time. For some people, especially those with claustrophobia, the thought of wearing the mask can feel overwhelming. The team may suggest that you try relaxation or breathing exercises or a psychologist can give you strategies to try. You may also be offered medicine to help you relax.

Tell the radiation therapist if wearing the mask makes you feel anxious. With support, many people get used to wearing it.

Proton therapy

This uses protons rather than x-ray beams. Protons are tiny parts of atoms with a positive charge. Proton therapy is used for some types of brain and spinal cord tumours, and tumours near sensitive areas.

A proton therapy machine has been installed in South Australia. It is hoped it will start treating patients soon. Currently, there is funding in special cases to allow Australians to travel overseas for proton therapy.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy side effects generally occur in the treatment area. They are usually temporary, but some may last for a few months or years, or be permanent. The side effects vary depending on whether the tumour is in the brain or spinal cord. They may include:

- nausea – can occur several hours after treatment

- headaches – can occur throughout the course of treatment

- tiredness or fatigue – worse at the end of the treatment; can continue to build after treatment, but usually improves over a month or so

- dry, itchy, red, sore or flaky skin – may occur in the treatment area; it is usually mild and happens at the end of the treatment course and lasts 1–2 weeks before going away

- hair loss – may occur in a patch in the area of the head receiving treatment; usually temporary but in some cases permanent; if hair grows back, the texture or colour may be different

- dulled hearing – may occur if fluid builds up in the middle ear and is usually temporary but may be permanent.

Radiation therapy side effects specific for spinal cord tumours may include sore or dry throat and swallowing problems (if the neck area is treated) or diarrhoea (if the lower spine is treated). Both are temporary. Talk to your radiation oncology team about how to manage any side effects.

A small number of adults who have had radiation therapy to the brain have side effects that appear months or years after treatment. These are called late effects, and can include symptoms such as poor memory, confusion and headaches.

High-dose radiation to the pituitary gland can cause it to produce too little of some hormones. This can affect body temperature, growth, sleep, weight and appetite. The hormone levels in your pituitary gland will be monitored during and after treatment.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to healthy cells.

You may have chemotherapy after surgery or radiation therapy. Chemotherapy may also be given at the same time as radiation therapy (chemoradiation). For a brain tumour, you usually have chemotherapy as capsules or tablets that you swallow, but you may also have it as a liquid through a drip inserted into your vein (intravenously).

A structure known as the blood–brain barrier helps protect the brain from substances in the blood, such as germs or chemicals. Only certain types of chemotherapy drugs can get through this barrier.

Temozolomide is the most commonly prescribed chemotherapy drug to treat grade 4 glioma brain tumours. It is given as a capsule you take at home. You will be instructed to take it for a set number of days, which is then followed by a rest period. This is called a cycle.

You are likely to have up to 6 cycles of temozolomide, though it may continue for longer.

Your doctor may suggest a different dosage or another chemotherapy drug that is more suitable for your situation. Other drugs include lomustine and PCV (procarbazine, lomustine and vincristine).

Side effects of chemotherapy

There are many possible side effects of chemotherapy, depending on the type of drugs you are given. Talk to your doctor about ways to reduce or manage any side effects you have. Side effects are mostly mild with temozolomide and may include:

- nausea or vomiting

- tiredness, fatigue and lack of energy

- increased risk of infection

- mouth sores and ulcers

- diarrhoea or constipation

- loss of appetite

- skin rash

- liver damage

- breathlessness due to low levels of red blood cells (anaemia)

- low levels of platelets (thrombocytopenia), increasing the risk of abnormal bleeding

- reduction in the production of blood cells in the bone marrow; you will usually have regular blood tests to monitor your blood levels

- damage to ovaries or testicles, which can make you unable to have children naturally (infertile).

In some cases your hair may become thinner or patchy, but it is rare to lose all your hair with chemotherapy for brain and spinal cord tumours.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a drug therapy that targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing or spreading. These drugs circulate through the body, but work in a more focused way than chemotherapy and often have fewer side effects.

A range of new targeted therapy drugs are being developed to match the molecular profile of each person’s cancer cells. For brain tumours, researchers are studying how to target genes such as BRAF, NTRK and IDH. These advances will help make personalised treatments possible.

Immunotherapy and brain tumours

Immunotherapy is not currently a standard treatment option for primary brain tumours. This is in part because of the way the brain’s immune system works. New immunotherapy drugs are being tested in clinical trials. These include treatments to help the immune system better recognise cancer cells (e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab), vaccines against cancer cells (e.g. PEP-CMV, DCVax), viruses to infect cancer cells (e.g. PVSRIPO, G47Δ), and treatments that change the patient’s own immune cells (e.g. CAR-T cell therapy).

Immunotherapy may be used to treat certain types of cancer that have spread to the brain (metastasised).

Treatments to control symptoms

Steroids

Steroids (also known as corticosteroids) are made naturally in the body, but they can also be made and used as drugs. Brain tumours and their treatments can both lead to swelling in the brain. Steroids may help to reduce this swelling. They can be given before, during and after surgery and radiation therapy. The most commonly used steroid for people with brain tumours is dexamethasone. It is usually given as a tablet but may be given in a vein (intravenously) if needed.

Side effects of steroids

The side effects you may experience with steroids depend on the dose and length of treatment:

Short-term use – You may experience increased appetite and weight gain; trouble sleeping; restlessness; mood swings; anxiety; and, in rare cases, more serious changes to thinking and behaviour. In people who have diabetes, steroids can quickly lead to high or unstable blood sugar levels. These short-term side effects can be managed. Eating before taking steroids can reduce the chance of them irritating your stomach.

Longer-term use – If steroids are taken for several months, they can cause puffy skin (fluid retention or oedema) in the feet, hands or face; high blood pressure; weight gain; unstable blood sugar levels; diabetes; muscle weakness; and loss of bone density (osteoporosis). You are more likely to get infections. Your doctor may change your dose to manage your side effects. Most side effects go away after treatment ends.

Anticonvulsants

You may be given anticonvulsants to help control seizures which can also affect your mood and energy. An experienced counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist can help you manage any mood swings or behavioural changes. If you or your family are worried about side effects, talk to a doctor, nurse or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Palliative treatment

Palliative treatment helps to improve quality of life by managing the symptoms when a brain tumour is no longer curable. As well as slowing the spread of cancer, palliative treatment can relieve pain and help with other symptoms. Treatment may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or other medicines.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs. You can have palliative care services in the home as well as in a hospital or in residential care.

Living with a brain or spinal cord tumour

A brain or spinal cord tumour and its treatment can change how the mind and body work. You or your family members may notice changes in how you speak and your personality, memory and other thinking skills, movement, balance or coordination.

It’s common to feel very tired. An occupational therapist can help you to manage the effects of this fatigue and give you strategies to cope.

Other types of changes you experience will depend on the part of the brain affected by the tumour and what treatment you have had. If you or your family feel like you are behaving differently, talk to your doctor, nurse or cancer care coordinator.

The changes may be difficult to handle, and they could affect how you feel about yourself and your relationships. Talking to a counsellor or someone who has had a similar experience may help. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to see what support is available.

Financial support for people with disabilities

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) provides Australians aged under 65 who have a permanent and significant disability with funding for support and services. The NDIS may be able to help a person whose everyday activities have been impacted by a brain tumour. For more information, talk with your rehabilitation team.

If your GP refers you to a rehabilitation specialist as part of a Chronic Disease GP Management Plan or Team Care Arrangement, you may be eligible for a Medicare rebate for up to five visits each year.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is treatment designed to help people recover from or adjust to injury or disease. After treatment for a brain or spinal cord tumour, most people will have a rehabilitation assessment to identify what they need help with and ways to manage changes. A range of health professionals offer various therapies to help restore your previous abilities or help you adjust to changes or long-term effects.

Types of rehabilitation

A range of therapies can support you in your recovery. These may be available at your cancer treatment centre, community therapy service or through a rehabilitation specialist at a rehabilitation hospital.

You may also be referred to allied health professionals (e.g. physiotherapist, occupational therapist). Ask to see a therapist experienced in working with people after treatment for brain or spinal cord tumours.

Physiotherapy

Your physical abilities may be affected. Physiotherapy can help you learn how to move more easily, develop muscle strength and improve balance.

Moving and strengthening your muscles can reduce tiredness or weakness related to treatment. If you can’t move easily, you may be able to learn techniques, such as using a walking stick, to help you stay as independent as possible.

A neurophysiotherapist specialises in treating physical changes caused by damage to the central nervous system.

Cognitive rehabilitation

Your memory, language skills, concentration, planning and problem-solving skills (executive function) may be affected.

A neuropsychologist, speech pathologist or occupational therapist can help improve these cognitive skills. They may use memory strategies, speech therapy, technology such as

calendars and reminder alerts, and word puzzles.

Exercise

A physiotherapist or an exercise physiologist can give you advice on how to increase physical activity and exercise safely to improve circulation and mobility, reduce swelling, and increase both your heart and lung fitness. They will also help you find ways to return to activities you previously enjoyed.

To find a physiotherapist, visit the Australian Physiotherapy Association and to find an accredited exercise physiologist, visit Exercise and Sports Science Australia.

Speech therapy

Your ability to talk may be affected, which is often called aphasia. A speech pathologist could help to restore speech.

Speech pathologists also work with people who have difficulty swallowing food and drink

(called dysphagia).

To find a certified practising speech pathologist, visit Speech Pathology Australia.

Help with vision impairment

You may lose some or all of your sight as a result of a brain tumour, depending on what part of the brain is affected.

Vision Australia can teach you tips and strategies to live independently.

Occupational therapy

If you are finding it harder to do everyday personal activities (e.g. showering, dressing, preparing a meal) or more complex activities (e.g. work and driving), an occupational therapist may be able to help. They can offer a range of strategies and aids to help you manage fatigue, physical and cognitive changes so you can improve or maintain your independence.

To find an occupational therapist working in private practice, visit Occupational Therapy Australia.

Managing seizures

A brain tumour or its treatment can sometimes cause seizures (fits or convulsions). A seizure is a disruption to the normal patterns of electrical impulses in the brain. There are 2 main groups of seizures:

Generalised seizures – These occur when all of the brain is affected, and typically involve the whole body. The most common type is called a tonic-clonic seizure (previously known as a grand mal seizure).

A seizure often starts with a loss of consciousness. The person’s muscles may stiffen, their limbs may jerk rhythmically, and their breathing may be shallow for up to 2 minutes. They may bite their tongue, and lose bladder and bowel control.

Focal seizures – Also called partial seizures, these occur when only one area (lobe) of the brain is affected. Focal seizures affect one part of the body, such as an arm or leg.

Symptoms of focal seizures depend on the area of the brain involved. They may include twitching; jerking; tingling or numbness; not being able to speak; and changes in vision or hearing, strange tastes or smells, or a feeling of deja vu. Focal seizures may also cause a brief loss of consciousness, changes in mood, and memory loss just before, during and after the seizure.

Ways to prevent seizures

Seizures can often be prevented with anticonvulsant medicines (also called anti-epileptic or anti-seizure medicines). Feeling overstimulated or very tired can also increase your risk of having a seizure. Try to get 6–8 hours sleep each night. Drinking less alcohol may also help.

How to help someone having a seizure

- Remain calm and stay with the person while they are having a seizure. Refer to their Seizure Management Plan (see last tip in this list), if they have one.

- Do not hold them down or put anything in their mouth.

- Protect the person from injury (e.g. move hazards, lower them to the floor if possible, loosen their clothing, cushion their head and shoulders).

- Call Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance if it is the first seizure the person has had; if the person is injured; if there was food or fluid in the person’s mouth; if the seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes; or if you are unsure of what to do.

- Time how long the seizure lasts so you can tell the paramedics.

- After the jerking stops, roll the person onto their side to keep their airway clear. This is particularly important if the person has vomited, is unconscious or has food or fluid in their mouth.

- Watch the person until they have recovered, or the ambulance arrives.

- If the seizure occurs while the person is in a wheelchair or car, support their head and leave them safely strapped in their seat until the seizure is over. Afterwards, remove the person from their seat, if possible. Roll them onto their side if there is food, fluid or vomit in their mouth.

- Explain to the person what has occurred. In many cases, people are confused after a seizure.

- Allow the person to rest afterwards as most seizures are exhausting.

- For detailed information and an online tool for creating a Seizure Management Plan, visit Epilepsy Action Australia or call them on 1300 37 45 37.

Anticonvulsant medicines

Different types of anticonvulsant drugs are used to prevent seizures. You may need to have blood tests while you are taking anticonvulsants. This is to check whether the dose is working and how your liver is coping with the medicine.

Side effects of anticonvulsant drugs vary, but they may include tiredness, gum problems, shakes (tremors), nausea, vomiting, weight changes, depression, irritability and aggression.

If you are allergic to the medicine, you may get a rash. Tell your treatment team if you have any skin changes or other side effects. Your doctor can adjust the dose or try another anticonvulsant. Do not stop taking the medicine or change the dose without your doctor’s advice.

If you take anticonvulsants, you may need to avoid some foods. Check with your doctor before taking any herbal medicine, as it can change how some anticonvulsants work. Ask your doctor or pharmacist about potential interactions and foods to avoid.

Driving

Tumours, seizures, brain surgery and medicines (such as anticonvulsants and some pain medicines) can affect the skills needed to drive safely.

These skills include:

- good vision and perception

- ability to concentrate and plan

- processing speed and reaction time

- ability to remember directions

- good hand–eye coordination

- planning and problem-solving.

When you are diagnosed with any type of brain tumour, it is very important to ask your doctor how your condition or treatment will affect your ability to drive.

Your doctor will usually advise you not to drive for a while. You probably need to wait for some time before you drive again after surgery and possibly after radiation therapy.

There are also some set exclusion periods your doctor will follow after certain treatments or events such as seizures. If you have had seizures, legally you will need to be seizure-free for a period of time before you are allowed to drive. If you stop taking your anticonvulsant medicines, you will also need to be seizure-free for a period of time until you are allowed to drive.

Before you start driving again, always check with your doctor. Laws in Australia require drivers to let their driver licensing authority know about any permanent or long-term illness or injury that is likely to affect their ability to drive.

Your doctor can tell you if you should report your condition or if there are any temporary restrictions. The licensing authority may ask for information from your doctor to decide if you are medically fit to drive.

How to return to driving

- Have a driving assessment to check your ability to return to driving. This may include doing an off-road assessment or having an electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess seizure risk.

- See an occupational therapist driving assessor, a neurologist or rehabilitation specialist to work out the type of problems you may experience while driving (e.g. a slow reaction time). The focus of the assessment is not to suspend or cancel your licence: it is to work out if it is possible for you to safely return to driving.

- An occupational therapist may be able to teach you driving techniques to help with weaknesses or show you how to make changes to your car (such as extra mirrors). You may also be able to drive with restrictions, such as only in daylight, only in automatic cars or only short distances from home.

- Some people feel upset or frustrated if they have licence restrictions or can no longer drive. You may feel that you have lost your independence or worry about the impact on your family. It may help to talk to a counsellor or someone who has been through a similar experience. Depending on your situation and your health, it may be possible to return to driving later on.

- Follow any licence restrictions. If your doctor says you are not safe to drive, you must not drive unless they change that medical decision. If you ignore the restrictions, your licence may be suspended or cancelled. You may be fined if you drive while your licence has been suspended or cancelled. If you have an accident while driving, you could be charged with a criminal offence and your insurance policy will no longer be valid.

- For more information, talk to your doctor or visit Austroads.

Working

It can be hard to predict how well you will recover from treatment for a brain tumour, and if or when you will be able to return to work. This may also depend on the type of work you do.

Some people find it hard to concentrate or make decisions after they have treatment for a brain tumour. At least at first, it may not be safe to operate heavy machinery or take on a lot of responsibility. Your doctors and an occupational therapist can tell you whether it’s okay to return to work.

Talk to your employer about adjusting your duties or hours until you have recovered. In some cases, it won’t be possible to return to your former role. It may help to talk to a social worker, occupational therapist or psychologist, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 or join a brain tumour support group to try and come to terms with these changes.

Life after treatment

Some people continue to have regular treatment, but for those who finish their treatment, the cancer experience doesn’t usually end there.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry about the cancer coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the tumour hasn’t come back or spread. During these check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination and you may have blood tests or MRI scans. How often you see your doctor will depend on the type of tumour and treatments you had. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any new or changing symptoms or health problems.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, you may feel anxious. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

What if the tumour returns?

For some people, a brain or spinal cord tumour can come back or keep growing despite treatment. If the tumour returns, this is called a recurrence. Your treatment options will depend on your situation and the treatments you’ve already had, but may include surgery, radiation therapy combined with drug therapies including chemotherapy, or another systemic therapy.

Targeted therapy drugs attack specific features of cancer cells. Bevacizumab is a targeted therapy drug that can be used to treat advanced brain cancer. Bevacizumab is most helpful when the tumour is causing swelling in the brain. Your doctor will talk to you about the benefits and possible risks. Other targeted therapy drugs and immunotherapy may be available on clinical trials. Talk with your doctor about the latest developments and whether you are a suitable candidate.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that you used to enjoy, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication, even for a short time, may help. You may be eligible for Medicare rebated sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA also operates a free counselling program. Call 13 11 20 for more information.

Visit Beyond Blue or call them on1300 22 4636 for help with depression and anxiety.

For 24-hour support, visit Lifeline or phone 13 11 14.