What is cancer?

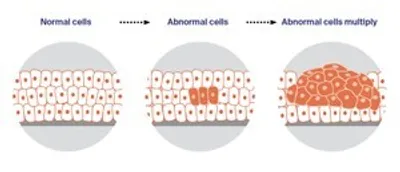

Cancer is a disease of the cells.

Cells are the body’s basic building blocks – they make up tissues and organs. The body constantly makes new cells to help us grow, replace worn-out tissue and heal injuries.

Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, so that each new cell replaces one lost. Sometimes, however, cells become abnormal and keep growing. These abnormal cells may turn into cancer.

In solid cancers, such as bowel cancer, the abnormal cells form a mass or lump called a tumour. In some cancers, such as leukaemia, the abnormal cells build up in the blood.

How cancer starts

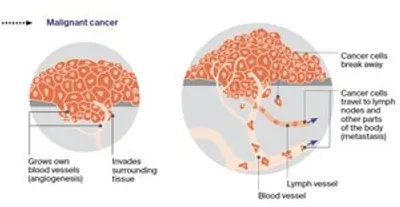

Not all tumours are cancer. Benign tumours tend to grow slowly and usually don’t move into other parts of the body or turn into cancer. Cancerous tumours, also known as malignant tumours, have the potential to spread. They may invade nearby tissue, destroying normal cells. The cancer cells can break away and travel through the bloodstream or lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

The cancer that first develops is called the primary cancer. It is considered localised cancer if it has not spread to other parts of the body. If the primary cancer cells grow and form another tumour at a new site, it is called a secondary cancer or metastasis. A metastasis keeps the name of the original cancer, unless this is unknown. For example, bowel cancer that has spread to the liver is called metastatic bowel cancer, even though the main symptoms may be coming from the liver.

How cancer spreads

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about cancer of unknown primary are below.

What is cancer of unknown primary?

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is when cancer cells are found in the body but the place the cancer began is not known. This means it is a secondary cancer that has spread to a new place from an unknown primary cancer somewhere else in the body.

With CUP, secondary cancers are commonly found in the liver, lung, abdomen, bones and lymph nodes, although they can grow in any part of the body.

Health professionals may also call CUP metastatic malignancy of unknown primary or occult primary cancer.

How do doctors know that it is a secondary cancer?

To diagnose secondary cancer, a specialist doctor called a pathologist looks at the cancer cells under a microscope. They can see that the cancer cells do not belong to the surrounding tissue, and this can be confirmed by further tests on the cells. With CUP, there are many different places in the body the cancer cells might have started.

How common is CUP?

Less than 5% of people diagnosed with cancer will have CUP. There are about 2650 new cases of CUP diagnosed each year in Australia. CUP is more common in people over the age of 60.

Why can’t the primary cancer be found?

For most people diagnosed with cancer, the primary cancer is easy to identify. Doctors conduct tests to find out where the cancer started to grow and to see if it has spread. Sometimes, however, cancer is found in one or more secondary sites and test results can’t show where the cancer began.

Reasons why your doctors cannot find the primary cancer include:

- the secondary cancer has grown quickly, but the primary cancer is still too small to be seen on scans or found on tests

- your immune system has destroyed the primary cancer, but not the secondary cancer

- the primary cancer can’t be seen on x-rays, imaging scans or endoscopies because it’s hidden by a secondary cancer that has grown close to or over it

- the cancer may be found in many parts of the body, but it isn’t clear from the scans or pathology tests which is the primary cancer.

Does it matter that the primary cancer can’t be found?

Finding the primary cancer can help doctors decide what treatment to recommend and give them a better idea of how the cancer is likely to respond to treatment. If the primary cancer can’t be found, tests on cells from the secondary cancer can often suggest what the primary cancer is most likely to be. This helps your doctor to plan treatment.

"I have found it complex to talk to people about my cancer … It seems incomprehensible to have a cancer that has spread but has no named starting point.” JANE

Can CUP be treated?

It can be frightening to be diagnosed with CUP, but there are treatments available. Your doctor will discuss the best options for you. The aim of treatment may be to:

- Slow the cancer’s growth or spread and prolong overall survival – In many cases, doctors may actively treat the cancer but not be able to cure it. In some cases, CUP presents in a pattern that is very like cancers from a known primary and can respond well to the same kind of treatment, even though the primary can’t be found.

- Relieve symptoms and maintain quality of life – CUP usually presents as advanced cancer, so treatment may focus on controlling symptoms and helping you plan the best possible future care for yourself. This is known as palliative treatment.

- Remove as much of the cancer as possible – In a small number of cases, CUP is found as a small area of cancer that may be able to be removed with surgery or high-dose radiation.

Will I need lots of tests?

Most people with a new diagnosis of cancer need several tests to find out how far the cancer has spread throughout the body.

People with CUP may need extra tests to try to find where the cancer started. The tests may take time and be tiring, particularly if you are feeling unwell. Waiting for the results can be a stressful time. You may also feel frustrated if the tests don’t find the primary cancer.

Your doctors will only suggest tests that they think are needed. It is okay to ask your doctors to explain the tests and the difference the results will make to your care. You may also want to ask if there are any specialised tests available at another hospital or treatment centre that may help find the primary cancer.

At some point, your doctors may decide that more tests won’t help find the primary cancer and it would be better to focus on starting treatment. Even if you decide not to have more tests, your family and friends may want you to have more tests. It may help to explain why you want to stop testing and share this information with them. Your medical team can provide support with these discussions.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of CUP are different for everyone and are related to the area where the secondary cancer is found. Some people have few or no symptoms; others have a range of symptoms that may include:

- swollen lymph nodes in the neck, underarm, chest or groin

- a lump or thickening

- feeling very tired (fatigue)

- poor appetite and/or feeling sick (nausea)

- unexplained weight loss

- fevers and night sweats

- cough, shortness of breath or discomfort in the chest

- pain in the bones, back, head, abdomen or elsewhere

- swelling of the abdomen

- change in bladder habits, such as needing to pee more often

- change in bowel habits, such as constipation or diarrhoea

- yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice).

Not everyone with the symptoms listed above will have cancer, but see your general practitioner (GP) if you are concerned.

What are the risk factors?

A risk factor is anything that increases your chance of developing cancer. CUP can have many different risk factors. Without knowing where the cancer started, you can’t know all of the specific risk factors. However, examples of things that increase your general cancer risk (including CUP) are getting older, smoking, unhealthy eating habits, not being physically active, drinking too much alcohol, spending too much time in the sun, a family history of cancer, and being overweight. Some of these things you can change and others you can’t. These risk factors may play a role in some but not all cases of CUP.

Are there different types of CUP?

Even if tests can’t find where the cancer started, your doctor will try to work out what type of cell the cancer developed from. Knowing the type of cell helps doctors work out what sort of treatment is most likely to be helpful.

Most cancers are cancers of the epithelial cells, which are found in the lining of the skin and internal organs. These cancers are known as carcinomas. In most people with CUP, doctors can tell that they have some sort of carcinoma. There are different types of carcinoma depending on which type of epithelial cell is affected. Your doctor will explain the type of CUP you have.

What are the different types of cancer of unknown primary?

Adenocarcinoma

Which cells are affected? mucus-producing (glandular) cells, which form part of the lining of many organs and can also group together to form structures called glands.

Where might it have started? bowel; breast; liver; lung; oesophagus; ovary; pancreas; prostate; stomach; uterus.

How common is it? makes up about 50% of CUP cases.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Which cells are affected? squamous cells, which are thin, flat cells normally found on the surface of the skin or in the lining of some organs.

Where might it have started? anus; cervix; head and neck area; lung; oesophagus; skin; vagina.

How common is it? makes up about 15% of CUP cases.

Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

Which cells are affected? specialised neuroendocrine cells found throughout the body that sometimes produce hormones.

Where might it have started? bowel; oesophagus; pancreas; stomach. Less commonly may start elsewhere such as in the lungs or gynaecological or urinary systems.

How common is it? makes up about 5% of CUP cases.

Poorly Differentiated Carcinoma

Which cells are affected? tests show that the cancer cells are a carcinoma, but don’t show the specific type of epithelial cell affected.

Where might it have started? not enough detail to suggest where the primary site may have been.

How common is it? makes up about 30% of CUP cases.

Undifferentiated Neoplasm (tumour)

Which cells are affected? unknown – tests show that the cells are cancerous, but not whether they are a carcinoma or another form of cancer (such as a sarcoma or melanoma).

Where might it have started? not enough detail to suggest where the primary site may have been.

How common is it? – makes up under 5% of CUP cases.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your GP will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist for further tests. The type of specialist you see will depend on your symptoms, the suspected location of the cancer and the types of tests you need. For example, you may see a gastroenterologist (digestive tract, bowel or stomach), gynaecologist (female reproductive system), urologist (urinary tract or kidneys; male reproductive system), respiratory physician or thoracic surgeon (chest and lung), neurosurgeon (brain and spinal cord), ear nose and throat surgeon, or haematologist (blood cells). Sometimes your main specialist will be a medical oncologist who treats all types of cancer.

If cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

GP – assists you with treatment decisions and works in partnership with your specialists in providing ongoing care

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Surgeon – surgically removes tumours and performs some biopsies; specialist cancer surgeons are called surgical oncologists

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiologist – analyses x-rays and scans; an interventional radiologist may also perform a biopsy under ultrasound or CT, and deliver some treatments

Pathologist – examines cells and tissue samples to determine the type and extent of the cancer

Nurse or nurse practitioner – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment; a nurse practitioner works in an advanced nursing role and may prescribe some medicines and tests

Palliative care specialists and nurses – work closely with the GP and cancer team to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life

Pharmacist – dispenses medicines and gives advice about dosage and side effects

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Physiotherapist, exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve fitness and wellbeing

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Psychologist, psychiatrist – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; may be a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

How is cancer of unknown primary diagnosed?

Before CUP is diagnosed, you will usually see your GP, who will ask about your symptoms and medical history, examine you, send you for tests and refer you to a specialist doctor.

The specialist will arrange extra tests to work out whether you have primary or secondary cancer. If the tests show that the cancer is secondary, more tests will be done to try to find the primary cancer. The tests you have depend on your health and symptoms, the location of the secondary cancer and the suspected location of the primary cancer.

If the tests find where the cancer started, the cancer is no longer an unknown primary. It will then be treated like the primary cancer type. For example, bowel cancer that has spread to the liver will be given the treatment for advanced bowel cancer.

Tests used to find where the cancer started

- blood and urine tests – samples of your blood and urine are sent to a laboratory to be checked for abnormal cells and chemicals called tumour markers

- biopsy – a tissue sample is taken from a tumour, enlarged lymph node or bone marrow and sent to a laboratory for examination; tests on the sample can suggest the primary site

- endoscopy – uses an instrument to look inside the body and take small tissue samples

- imaging tests – x-rays, ultrasounds and other scans create images of the inside of the body; PET–CT scans have been shown to help find the primary site in new cases of CUP

The diagnosis and treatment of CUP can be complex and you might need to travel to a specialist centre. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to ask about patient travel assistance that may be available to you.

Blood and urine tests

A full blood count is a test that checks the levels of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. Blood tests can also show how well the kidneys and liver are working. Urine and faeces (poo) may be tested to look for abnormal cells or bleeding coming from the bladder, kidneys or bowel.

Tumour markers

In some cases, blood, urine or tissue samples may be tested for tumour markers. These are proteins made by some cancer cells. High levels of tumour markers may suggest cancer. However, other conditions can also raise the levels of tumour markers, and some people with cancer have normal levels. Tumour marker levels can’t be used on their own to diagnose the primary cancer, but they may suggest certain types of cancer for your doctors to look for.

Biopsy

A biopsy is when doctors remove a sample of cells or tissue from an area of the body. A specialist doctor called a pathologist examines the sample under a microscope to look for signs of cancer and work out what type of cell is affected. This can point to where in the body the cancer may have started.

For a biopsy, you will usually have a local anaesthetic to numb the area. In some cases, you may need a general anaesthetic, which puts you to sleep.

Ways of taking biopsies

There are different ways of taking a biopsy and you may need more than one type. A biopsy is often done using an ultrasound or CT scan to guide the needle to the correct place. You might not have a biopsy if the cancer is too hard to reach or if you are too unwell for the procedure.

Common types of biopsies used to diagnose cancer include:

- fine needle aspiration – removes cells using a thin needle

- core biopsy – removes tissue using a hollow needle

- incision biopsy – cuts out part of a tumour

- excision biopsy – cuts out the whole tumour.

Tests on the biopsy sample

Using special stains (immunohistochemistry) – After the biopsy procedure, the sample will be sent to a laboratory, where a pathologist uses a series of stains on the sample. These stains may show changes in the cells or highlight markers (e.g. specific proteins) that are linked to certain types of cancer.

Looking at the molecular level – In some cases, you may be offered extra tests on the biopsy sample. These are called molecular or genomic tests, and they look for gene changes and other features in the cancer cells that may be causing them to multiply and grow. The results may suggest what the primary cancer is most likely to be and which targeted therapy drugs may work best to treat it.

Molecular testing for CUP is usually not covered by Medicare, which can make it expensive. Check what costs are involved and how helpful it would be. If you are having molecular testing as part of a clinical trial, the costs may be covered. Ask your cancer specialists for more information about these specialised tests.

Endoscopy

This procedure is used to look inside the body for any abnormal areas. It is done with an endoscope – a thin, flexible tube with a light and camera on the end. The endoscope is put into the body through a natural opening (such as the mouth) or a small cut made by the surgeon. The camera projects images onto a monitor so the doctor can see inside the body. If they see something suspicious, they can also take a tissue sample (biopsy) using the endoscope.

Common types of endoscopy

- bronchoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) – checks the lungs or respiratory tract (airways); tube inserted through the mouth or nose.

- colonoscopy – checks the colon (large bowel); tube inserted through the anus.

- colposcopy – checks the vagina and cervix; placed outside the vulva and vagina, held open by a speculum.

- cystoscopy – checks the bladder; tube inserted through the urethra.

- gastroscopy – checks the oesophagus, stomach and first part of the small bowel; tube inserted through the mouth.

- hysteroscopy – checks the uterus (womb); tube inserted through the vagina.

- laparoscopy – checks the abdominal cavity, liver, bowel, uterus and ovaries; tube inserted through small cuts in the abdomen.

- laryngoscopy – checks the larynx (voice box); tube inserted through the mouth.

- sigmoidoscopy – checks the lower part of the colon (large bowel); tube inserted through the anus.

- thoracoscopy – checks the lungs; tube inserted through a small cut in the chest.

Imaging tests

These scans create images of the inside of your body and provide different types of information. Your doctors will recommend the most useful scans for your situation. Ask your doctor or imaging centre what you will have to pay and whether Medicare covers the cost.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

X-ray

- How it works – uses low-energy beams of radiation to create images of parts of the body, such as bones and the chest

- How long does it take – 10-30 minutes

- What happens – you hold still in front of or on a machine while the images are taken; you might be injected with a dye (contrast) to improve the image

- Special notes – painless; the small dose of radiation will not make you give off radiation

Mammogram

- How it works – uses a low-dose x-ray to create an image of the inside of the breast

- How long does it take – 10-30 minutes

- What happens – your breast is placed between 2 x-ray plates, which press together firmly to spread the breast tissue

- Special notes – can be uncomfortable

Ultrasound

- How it works – uses soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or tumour; a computer turns the soundwaves into a picture of the inside of the body

- How long does it take – 10-20 minutes

- What happens – a cool gel is spread on your skin and a handheld device called a transducer sends out the soundwaves as it is moved across the area; some transducers are wands that can be inserted in a body cavity

- Special notes – usually painless, but can be uncomfortable

CT scan (computerised tomography scan)

- How it works – uses x-ray beams and a computer to create detailed pictures of the inside of the body; the scanner is large and round like a doughnut

- How long does it take – up to 30 minutes

- What happens – before the scan, you may be given a drink or injected with a dye (contrast) to make the pictures clearer; you lie still on a table that moves in and out of the scanner

- Special notes – painless; the dye may make you feel hot all over and leave a bitter taste in your mouth

PET–CT scan (positron emission tomography scan with CT scan)

- How it works – uses a low-dose radioactive solution to measure cell activity in different parts of the body; when combined with a CT scan it provides more detailed information about the cancer

- How long does it take – about 2 hours

- What happens – you are injected in the arm with a small amount of radioactive solution, wait 30–90 minutes for it to move through your body, and then have the scan; cancer cells take up more of the solution than normal cells do and light up on the scan

- Special notes – the solution leaves your body in urine after a few hours; you may be told to avoid children and pregnant women for a number of hours

Bone scan

- How it works – uses radioactive dye to show any abnormal bone growth

- How long does it take – several hours

- What happens – you are injected in the arm with a small amount of radioactive dye, wait 2–3 hours for it to move through your bloodstream to the bones, then your body is scanned; a larger amount of dye will usually show up in any areas of bone with cancer cells

- Special notes – the dye leaves your body in urine after a few hours; you may be told to avoid children and pregnant women for a number of hours

MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging scan)

- How it works – uses a magnet and radio waves to build up detailed pictures of an area of the body

- How long does it take – 30-90 minutes

- What happens – dye (contrast) may be injected into a vein to make the images clearer; you lie on a table that slides into a narrow metal cylinder that is open at both ends; the scan is noisy, so you will often be given earplugs or headphones

- Special notes – let the medical team know if you feel anxious, you may be given medicine to help you relax; people with some pacemakers or other metallic objects cannot have an MRI

Staging

Staging is a way to describe how far a cancer has spread. CUP cannot be given a stage because the primary cancer is not known and the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body when it is found. This is considered advanced cancer.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider test results; the type of CUP you have; where the cancer is located and how far it has spread through the body; how fast the cancer is growing; how well you respond to treatment; the impact the cancer has had on your health; and factors such as your age, fitness and medical history.

Although most cases of CUP can’t be cured, treatment can keep some cancers under control for months or years. Whatever the prognosis, palliative treatment can relieve symptoms such as pain to improve quality of life. It can be used at any stage of advanced cancer.

Discussing your prognosis and thinking about the future can be challenging and stressful. It is important to know that although the statistics for CUP can be frightening, they are an average and may not apply to your situation. Talk to your doctor about how to interpret any statistics that you come across.

Treatment for cancer of unknown primary

When tests have been unable to find the primary cancer, you will be given a diagnosis of CUP.

This is often a difficult time and it can be hard to accept that the primary site cannot be found. On the other hand, you may feel relieved that the tests are over and that the focus can now be on treating the cancer.

Your treatment plan

The treatment recommended by your doctors will depend on:

- where the secondary cancer is in the body and how far it has spread

- where they think the cancer started

- how quickly the cancer seems to be growing

- how you are feeling (your symptoms)

- your general health, age and treatment preferences

- what treatments are currently available and whether there are any newer treatments available on clinical trials

- the aim of treatment (whether to remove as much of the cancer as possible, slow the cancer’s growth or relieve symptoms).

The most common treatment for CUP is chemotherapy, and many people also have radiation therapy and surgery. Some cancers may respond to hormone therapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy. Your doctor may suggest a combination of treatments.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth. Medical oncologists and some specialists prescribe chemotherapy to shrink a cancer and relieve symptoms. It can be used with radiation therapy or surgery to try to kill a collection of cancer cells in the body.

How chemotherapy is given – Generally, chemotherapy is given through a drip inserted into a vein (intravenously), but some types are taken by mouth as tablets. As different cancer cells respond to different chemotherapy drugs, you may have a combination of drugs. It is common in CUP to receive 2 chemotherapy drugs.

Chemotherapy is commonly given as a period of treatment followed by a break. This is called a cycle. The length of the cycle depends on the drugs used. Usually, you will have chemotherapy during day visits to a hospital or treatment centre. Sometimes a short stay in hospital is needed.

Number of sessions – The total number of treatment cycles you have depends on your situation. With CUP, after 2 or 3 cycles you will usually have imaging scans to test how the cancer is responding to the drugs. The results will let you weigh up the benefits of continuing the treatment against the effects on your quality of life. It may also mean a change in treatment if the chemotherapy is not shrinking the cancer.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Most chemotherapy drugs cause side effects. These are usually temporary, and can be prevented or reduced. The most common side effects include feeling sick (nausea), vomiting, mouth sores, tiredness, loss of appetite, diarrhoea or constipation, and some thinning or loss of hair from your body and head.

Chemotherapy weakens the body’s immune system, making it harder to fight infections. You will have regular blood tests to check your immune system. If your temperature rises to 38°C or above, contact your medical team or go to the nearest hospital emergency department immediately.

The side effects of some chemotherapy drugs can be longer lasting or permanent (e.g. damage to the heart or nerves). Ask your doctor to explain the potential risks and benefits of the chemotherapy recommended for you.

Hormone therapy

Hormones are substances that occur naturally in the body. Some cancers depend on hormones to grow (e.g. oestrogen may help breast cancer grow). Hormone therapy aims to lower the amount of hormones in the body in order to slow or stop the cancer’s growth. The treatment may be given as tablets you swallow or injections. If tests show that the CUP may have started as a cancer that is hormone dependent, your doctor might suggest hormone therapy. It is sometimes used with other treatments.

Side effects of hormone therapy

The side effects of hormone therapy will vary depending on the hormones you are given. Common side effects include tiredness, nausea, appetite changes, weight gain, mood changes, pain in the joints, thinning of the bones (osteoporosis), hot flushes and erection problems.

It is important to tell your treatment team about any side effects you have from drug therapies. Side effects can be better managed when reported early. You may be given medicine to prevent or reduce side effects. Sometimes, your doctor may delay treatment or reduce the dose to lessen side effects.

Targeted therapy

This is a type of drug therapy that attacks specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Many targeted therapy drugs are given by mouth as tablets, but some are given by injection.

Only a small number of CUP tumours will be suitable for targeted therapy. Your doctors will need to test the cancer to see if the cells have a particular cell change that is helping the cancer grow.

Side effects of targeted therapy

Targeted therapy drugs minimise harm to healthy cells, but they can still have side effects. These side effects vary greatly depending on the drug used and how your body responds. Common side effects of targeted therapy include skin rashes, fever, tiredness, joint aches, nausea, diarrhoea, bleeding and bruising, and high blood pressure.

It is important to tell your treatment team about any side effects you have from drug therapies. Side effects can be better managed when reported early. You may be given medicine to prevent or reduce side effects. Sometimes, your doctor may delay treatment or reduce the dose to lessen side effects.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Sometimes the results of specialised tests on a CUP tumour may suggest that immunotherapy could help to treat the cancer.

More evidence is needed to tell whether immunotherapy works for CUP, so it isn’t funded on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) yet. However, immunotherapy may be accessed if tests strongly suggest you have one of the other cancer types that are funded on the PBS. Immunotherapy may also sometimes be accessed through clinical trials.

It is important to tell your treatment team about any side effects you have from drug therapies. Side effects can be better managed when reported early. You may be given medicine to prevent or reduce side effects. Sometimes, your doctor may delay treatment or reduce the dose to lessen side effects.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. The radiation is usually in the form of x-ray beams.

Most people with CUP have radiation therapy to relieve symptoms, such as pain, bleeding, difficulty swallowing, bowel blockages, shortness of breath, and tumours pressing on blood vessels or nerves or within bones.

Having radiation therapy – People with CUP are most likely to have external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), which is given from a machine outside the body. To help plan treatment, you will usually have a CT scan of the treatment area. To ensure that the same area is treated each time, the radiation therapist will make a few small dots (tattoos) on your skin that may be temporary or permanent. Radiation treatments are painless, although it can be uncomfortable lying on a hard treatment table.

Number of sessions – The total number of treatments and when you have them will depend on your situation. You might need only a single treatment, or you may need them every weekday for several weeks.

Chemoradiation – If squamous cell carcinoma spreads to the lymph nodes (e.g. in the neck or groin area), you may be offered a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. This treatment is known as chemoradiation. It may be given for up to 7 weeks.

Side effects of radiation therapy

The side effects will depend on the area of the body being treated and the dose of radiation. The most common side effect is fatigue. Nausea or altered sense of taste can sometimes occur. Your skin may become dry and itchy in the area treated, look red or sunburnt and feel sore.

Side effects tend to develop as you go through radiation therapy, and most improve or go away in the weeks after you finish treatment. Talk to your doctor or nurse about ways to manage any side effects you have.

Surgery

Surgery removes cancer from the body. It is mostly used if cancer is found at an early stage. If CUP has already spread to a number of places in the body, surgery may not be the best treatment. If surgery is used, it may remove only some of the cancer. Surgery is often followed by radiation therapy or chemotherapy to kill or shrink any cancer cells left in the body.

If the cancer is found only in the lymph nodes in the neck, underarm or groin, it may be possible to remove all of it with an operation. This is called a lymph node dissection or lymphadenectomy. Sometimes surgery can help with symptoms – for example, to relieve pain caused by the tumour pressing on a nerve or organ.

Side effects of surgery

After surgery, you may have some side effects. These will depend on the type of operation you have. Your surgeon will talk to you about the risks and complications of your procedure. These may include infection, bleeding and blood clots. You may experience pain after surgery, but this is often temporary. Talk to your doctor or nurse about pain relief.

If lymph nodes have been removed, you may develop lymphoedema. This is swelling caused by a build-up of lymph fluid in part of the body, usually in an arm or leg. For more details, speak to your nurse, visit the Australasian Lymphology Association or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Palliative treatment

Most people with CUP receive palliative treatment. This is treatment that aims to slow the spread of cancer and relieve symptoms without trying to cure the disease.

Cancer treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or other medicines are often given palliatively. It is possible that palliative treatment may make you feel better and also help you live longer.

You might think that palliative treatment is only for people at the end of their life, but it may help at any stage of advanced cancer. It is about living for as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

What is palliative care?

Palliative care supports the needs of people with a life-limiting illness in a holistic way.

The main goal is to help you maintain your quality of life by dealing with your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs. Palliative care also provides support to families and carers.

Specialist palliative care services don’t prescribe cancer treatments, but help people with CUP manage symptoms related to the cancer. They can also help you work out how to live in the most fulfilling way you can. You can ask your doctor for a referral.

Managing symptoms and side effects

Symptoms and side effects vary from person to person – you may have none, a few or many.

This section describes the most common symptoms and side effects experienced during treatment for CUP. You may have others not mentioned here. Talk to your treatment team about ways to manage any symptoms and side effects you have.

Pain

Many people with cancer worry that they will be in pain. Not everyone will have pain, and those who do may find the pain comes and goes. Pain is affected by the location of the cancer and its size. Ways to relieve pain include:

- pain medicines, such as paracetamol, ibuprofen and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids (e.g. oxycodone, morphine)

- medicines that are normally used for other conditions, such as antidepressants and anticonvulsants (known as adjuvant analgesics)

- procedures to block pain signals (e.g. nerve blocks or spinal injections)

- therapies, such as massage, meditation, relaxation, hypnotherapy, exercise and physical therapy

- psychological therapies that can change the way you think about and respond to pain

- cancer treatments used palliatively.

Often a combination of methods is needed and it may take time to find the right pain relief. If one method doesn’t work, you can try something else. Be sure to tell your doctor and pharmacist of all medicines you take.

Using cancer treatments to control pain

Chemotherapy, radiation therapy and surgery are common cancer treatments. They can sometimes be used palliatively to reduce pain by helping to remove its cause.

Radiation therapy – This treatment can be used to relieve many types of pain. The most common form of radiation therapy for pain is external beam radiation therapy. If cancer has

spread to many places in the bone and is causing pain, you may have another form of radiation therapy.

Cancer drug therapies – In some cases, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy

and immunotherapy can shrink a tumour that is pressing on nerves or organs and causing pain.

Surgery – Some people have an operation to remove part or all of a tumour. Surgery can also be used to treat a serious condition such as a bowel blockage (obstruction) that is causing pain, or to reduce the size of a cancer and improve how well chemotherapy and radiation therapy work.

Pain management experts – Your GP or oncologist may be able to suggest effective medicine, but if you are still uncomfortable, ask to see a palliative care specialist. Good pain control is one of the major ways a specialist palliative care team can help. How and where the pain is

felt, and how it affects your life, may change. Regular check-ups with pain management experts can help keep the pain under control.

Fatigue

For many people, feeling tired and lacking energy (fatigue) can be the most difficult symptom to manage. It can be very frustrating if other people don’t understand how you’re feeling.

Fatigue can be caused by a range of things, such as:

- the cancer itself or cancer treatments

- low levels of red blood cells (anaemia) or high levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcaemia)

- drugs such as pain medicines, antidepressants and sedatives

- infection

- loss of weight and muscle tone

- anxiety or depression

- lack of sleep

- poorly managed pain.

Tips for managing fatigue

- Pace yourself. Spread your activities throughout the day and take rest periods in between.

- Try to do gentle exercise. Research shows this reduces tiredness and preserves muscle strength. Even walking to the letterbox or getting up for meals can help.

- Speak to an occupational therapist about ways to conserve energy.

- Have a short nap (no more than 30 minutes) during the day. This can refresh you without making it hard to sleep well at night.

- Talk to your doctor if you often feel anxious or sad, or if you are having trouble sleeping at night.

Download our fact sheet ‘Fatigue and Cancer’

Nausea

Feeling sick in the stomach (nauseated) is an unpleasant symptom that may be caused by the cancer itself. Nausea can also be a side effect of some types of chemotherapy, but anti-nausea medicines can often prevent or manage this.

Other causes of nausea include:

- treatment with radiation therapy

- stress or anxiety

- too much or too little of a mineral in the blood (e.g. calcium)

- drugs used to control other symptoms (e.g. morphine for pain)

- the kidneys not working properly

- a bowel blockage (obstruction) or constipation

- increased pressure around the brain as a result of cancer in the brain or cancer affecting the flow of fluid around the brain and spinal cord.

Tips for easing nausea

- Eat small meals as often as you can.

- Eat cold foods, such as sandwiches, stewed fruit, salads or jelly.

- Have food or drink that contains ginger, such as ginger ale, ginger tea or ginger cake.

- Talk to your doctor or nurse about anti-nausea drugs or treatments that can help relieve constipation.

- Try to reduce stress by using meditation or relaxation techniques. Listen to our podcast ‘Finding Calm During Cancer‘

- Avoid strong odours and cooking smells.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Loss of appetite

Not feeling like eating is a common problem faced by people with CUP. This may be caused by the cancer itself or side effects of treatment. You may not enjoy the way food tastes or smells, or you may be worried about the diagnosis and treatment. You might also not want to eat much if you are feeling sick (nauseated) or have a sore mouth or oral thrush infection. These problems can often be managed, so let your treatment team know.

You may go through periods of having no appetite. These may last a few days or weeks, or be ongoing. During these periods, it may help to have liquid meal substitutes. These are high-kilojoule drinks containing some of the major nutrients needed by your body. Drinking these may help keep your energy levels up during periods when your appetite is poor.

Tips for when you don’t feel like eating

- Have small meals and snacks frequently throughout the day.

- Use small dishes so food isn’t “lost” on the plate (e.g. serve soup in a cup).

- Use lemon juice, fresh herbs, ginger, garlic or honey to add more interesting flavours to food.

- Sip fluids throughout the day. Add ice-cream, yoghurt or fruit to drinks to increase the kilojoules.

- Choose full-fat foods over low-fat, light or diet versions.

- If you have a sore mouth, eat soft food, such as scrambled eggs or stewed fruit.

- Ask your dietitian or doctor to recommend the right nutritional supplement for you to help slow weight loss and maintain your muscle strength.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Breathlessness

Some people with CUP experience shortness of breath. Causes include:

- fluid surrounding the lungs (pleural effusion)

- an infection in the lungs

- a blood clot in the lungs (pulmonary embolism)

- pressure from the cancer itself or from a swollen abdomen

- anaemia (low levels of red blood cells).

Treatment will depend on the cause. You may need fluid drained from the chest (pleural tap) or medicine for an infection or other lung problem. A low-dose opioid medicine is sometimes prescribed.

Feeling short of breath may make you feel anxious, which can make the breathlessness worse. Your doctor or a psychologist can help you find ways to manage any anxiety.

Tips to help your breathing

- Use a battery-operated handheld fan or open a window to increase airflow near your face.

- Sit up straight to ease your breathing or lean forward on a table with an arm crossed over a pillow. Try sleeping in a more upright position.

- Try relaxation or breathing techniques to see if they help. A physiotherapist or psychologist can teach you these techniques. You can also try listening to recorded meditation or relaxation exercises.

- Ask someone else to breathe in time with you so you can focus on slowing your breath to their pace.

Listen to our podcast episode ‘Managing Breathlessness when Cancer Is Advanced’

Seeking support

Living with a CUP diagnosis

When you are first diagnosed with CUP, and throughout the different stages of treatment, you may experience a range of emotions.

You may also find that some people are supportive, but others don’t know what to say to you. This can be difficult and leave you feeling confused and upset.

Many people with CUP find it hard to believe that the primary cancer can’t be located. The “unknown” aspect of the disease can make them feel scared and lonely, as well as frustrated when they are looking for information and support.

For many people with CUP, the cancer cannot be cured. Talking to your health care team can help you understand your situation and plan for your future care. Palliative treatments may stop the cancer growing and allow you to continue doing the things you enjoy for months or even several years.

It may help to talk about your feelings. Your partner and your family members and friends can be good sources of support, or you might prefer to talk to members of your treatment or palliative care team; a social worker, psychologist or counsellor; or your spiritual adviser.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who are living with advanced cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living with CUP.

How you might feel

Being diagnosed with CUP can be stressful. It is natural to have a wide variety of emotions, including anxiety, anger, fear, sadness and resentment. These feelings may become stronger over time as you adjust to the side effects of treatment.

Everyone has their own ways of coping. There is no right or wrong way. It is important to give yourself time to deal with the emotions that a cancer diagnosis can cause.

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have cancer.

If you think you may be depressed or feel that your emotions are affecting your day-to-day life, talk to your GP. Counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.

Practical support

A cancer diagnosis can affect every aspect of your life and may create practical and financial issues. There are many sources of support to help you, your family and carers navigate the cancer experience. These include benefits and programs to ease the financial impact; home care services; aids and appliances; support groups; and counselling services.

Availability of services may vary depending on where you live, and some services will be free but others might have a cost. For more information, talk to the social worker or nurse at your hospital or treatment centre, or get in touch with Cancer Council 13 11 20.