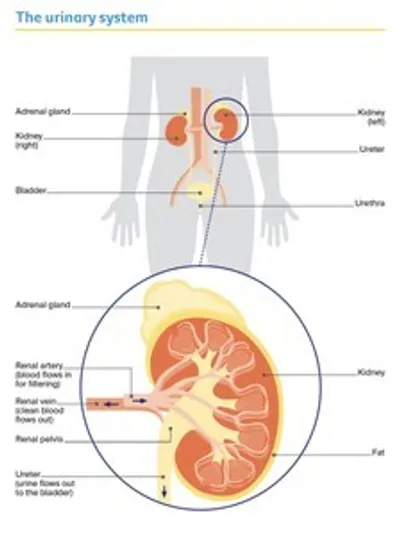

The kidneys

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist.

They are found deep inside your abdomen (belly), positioned near the middle of your back, on either side of the spine.

The kidneys are part of the body’s urinary system, which also includes the:

- ureters – tubes that take urine from the kidneys to the bladder

- bladder – a hollow sac that stores urine (wee) until you need to urinate

- urethra – a tube that takes urine from the bladder to outside the body.

An adrenal gland sits above each kidney. The adrenal glands produce a number of hormones. Although these glands are not part of the urinary system, kidney cancer can sometimes spread to them.

What the kidneys do

Filter blood – The main role of the kidneys is to filter and clean the blood. Blood flows through the renal artery into each kidney, where it is filtered through tiny networks of tubes called nephrons. The clean blood then flows out through the renal vein to the rest of the body.

Make urine – When the kidneys filter the blood, they remove excess water and waste products to make urine (wee or pee). The urine collects in an area of each kidney called the renal pelvis, and then flows through the ureters into the bladder.

Produce hormones – The kidneys also help your body control how much blood it needs. They do this by making hormones that regulate blood pressure and trigger the production of red blood cells.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about kidney cancer are below.

What is the main type of kidney cancer?

Kidney cancer is cancer that starts in the cells of the kidney. Most kidney cancers are renal cell carcinoma (RCC), sometimes called renal cell adenocarcinoma. RCCs start in the cells lining the tiny tubes found in the nephrons.

In the early stages of RCC, the tumour is in the kidney only. Usually one kidney is affected, but in rare cases there is a tumour in both kidneys.

As the cancer grows, it can spread to areas near the kidney, such as the surrounding fatty tissue, veins, adrenal glands, lymph nodes, ureters or the liver. It may also spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs, bones or brain.

Subtypes of renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

clear cell

- makes up about 80% of RCC cases

- cancer cells look empty or clear

papillary

- makes up about 10–15% of RCC cases

- cancer cells are arranged in finger-like fronds

chromophobe

- makes up about 5% of RCC cases

- cancer cells are large and pale

other types of RCC

- make up about 5–10% of RCC cases

- include renal medullary carcinoma, collecting duct carcinoma, MiT family translocation RCC, sarcomatoid RCC and other very rare types

Are there other types of kidney cancer?

RCC is the most common type of kidney cancer, but there are other less common types:

Urothelial carcinoma (or transitional cell carcinoma) – This can begin in the ureter or in the renal pelvis, where the kidney and ureter meet. It is also known as upper tract urothelial cancer.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Upper Tract Urothelial Cancer’

Wilms tumour (or nephroblastoma) – This type of kidney cancer is most common in younger children, but it is still rare.

Visit Children’s Cancer for more information.

Secondary cancer – Very rarely, cancer can spread from a primary cancer somewhere else in the body to the kidney. This is known as secondary cancer (metastasis). This secondary cancer is not kidney cancer and it behaves more like the primary cancer.

Download the Cancer Council booklet about the primary cancer

How common is kidney cancer?

Each year about 4700 Australians are diagnosed with kidney cancer. Men are twice as likely as women to be diagnosed with kidney cancer. It is the sixth most common cancer in men and the tenth most common cancer in women (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers). It is more common in people over 50, but it can occur at any age.

What are the symptoms?

Most people with kidney cancer have no symptoms and many are diagnosed with the disease when they see a doctor for an unrelated reason. If symptoms occur, they usually include:

- blood in the urine (haematuria) or a change in urine colour – it may look red, dark, rusty or brown

- pain in the lower back or side not caused by injury

- a lump in the side or abdomen (belly)

- constant tiredness

- unexplained weight loss

- fever (not caused by a cold or flu).

Cancer can affect the amount of hormones produced by the kidneys. If this affects blood production, it can lead to a low red blood cell count (anaemia), a high red blood cell count (polycythaemia) or high levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcaemia). Sometimes, these problems can cause symptoms such as fatigue, dizziness, headaches, constipation, abdominal (belly) pain and depression.

The symptoms listed above can also occur with other illnesses, so they don’t necessarily mean you have kidney cancer – only testing can confirm a diagnosis. If you are concerned, make an appointment with your general practitioner (GP).

“Kidney cancer can be a silent cancer until it is quite advanced, so I do feel thankful that it was discovered incidentally, when it was small and easier to treat.” CHRIS

What are the risk factors?

The exact cause of kidney cancer is not known. Research shows that people with certain risk factors are more likely to develop kidney cancer. Having a risk factor does not mean you will develop kidney cancer, and some people develop kidney cancer without having any known risk factors. If you are concerned, talk to your doctor.

Risk factors for kidney cancer include:

- smoking – people who smoke have almost twice the risk of developing kidney cancer as those who don’t smoke. About 1 in 3 kidney cancers are thought to be related to smoking; the longer a person smokes and the more they smoke, the greater the risk

- obesity – too much body fat may cause changes to some hormones that can lead to kidney cancer

- high blood pressure – whatever the cause, high blood pressure increases the risk of kidney cancer

- kidney failure – people with end-stage kidney disease have a higher risk of developing kidney cancer

- family history – people with a parent, brother or sister (first-degree relative) with kidney cancer are at increased risk

- inherited conditions – about 2–3% of kidney cancers develop in people who have particular inherited syndromes, including von Hippel–Lindau disease, Birt-Hogg–Dubé syndrome, hereditary papillary RCC, hereditary leiomyomatosis RCC, tuberous sclerosis, and Lynch syndrome.

If you are worried about your family history or whether you have inherited a particular syndrome, talk to your doctor about having regular check-ups or ask for a referral to a family cancer clinic. To find out more, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your GP will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist such as a urologist. The specialist will arrange further tests. If kidney cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

GP – assists you with treatment decisions and works in partnership with your specialists in providing ongoing care

Urologist – diagnoses and treats diseases of the urinary system, and the male reproductive system; performs surgery

Nephrologist – diagnoses and treats conditions that cause kidney (renal) failure or impairment; may be consulted by your urologist when planning surgery

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiologist – analyses x-rays and scans; an interventional radiologist may also perform a biopsy under ultrasound or CT, and deliver some treatments

Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout your treatment

Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT, and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Physiotherapist, Exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve fitness and wellbeing

Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Palliative Care Specialist and Nurses – work closely with the GP and cancer team to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life

How is kidney cancer diagnosed?

Most kidney cancers are found by chance when a person has an ultrasound or another imaging scan for an unrelated reason.

If your doctor suspects kidney cancer, you may have some of the following tests, but you are unlikely to need them all.

Blood and urine tests

You will probably have urine and blood tests to check your general health and look for signs of a problem in the kidneys. These tests do not diagnose kidney cancer. They may include:

- a full blood count to check the levels of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets

- tests to check how well your kidneys are working

- blood chemistry tests to measure the levels of certain substances in the blood (e.g. high levels of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase could be a sign that kidney cancer has spread to the bones).

Imaging scans

Various imaging scans can create pictures of the inside of your body and provide different types of information. You will usually have at least one of the following imaging scans.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound uses soundwaves to create pictures of your internal organs. These might show if there is a tumour in your kidney. During an ultrasound, you will lie on a bench and uncover your abdomen (belly) or back. A cool gel will be spread on your skin, and a small handheld device called a transducer will be moved across the area. The transducer creates soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or tumour. A computer turns the soundwaves into a picture. An ultrasound scan is painless and usually takes 15–20 minutes.

CT scan

A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-ray beams and a computer to create a detailed picture of the inside of the body. If kidney cancer is suspected on an ultrasound, your doctor will usually recommend a CT scan. This will help find any tumours in the kidneys, and provide information about the size, shape and position of a tumour. The scan also helps check if a cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other organs and tissues.

CT scans are usually done at a hospital or radiology clinic. You may be asked to fast (not eat or drink) for several hours before the scan to make the pictures clearer and easier to read.

Before the scan, a dye may be injected into a vein in your arm. This dye, known as contrast, helps make the pictures clearer. It travels through your bloodstream to the kidneys, ureters, bladder and other organs. The dye might make you feel flushed and hot for a few minutes and you could feel like you need to pass urine. These effects won’t last long.

During the scan, you will need to lie still on a table that moves in and out of the scanner, which is large and round like a doughnut. This painless test takes about 30–40 minutes.

MRI scan

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed, cross-sectional pictures of the inside of your body. Most people with kidney cancer won’t need an MRI, but it might be used to check whether cancer has spread from the kidney to the renal vein or spinal cord.

Let your medical team know if you have a pacemaker or any other metallic object in your body. If you do, you may not be able to have an MRI scan, although some newer devices are safe to go into the scanner. Before the MRI, you may be injected with a dye to help make the pictures clearer. An MRI without dye may be used instead of a CT scan if you have pre-existing kidney problems and cannot have the dye.

During the scan, you will lie on an examination table that slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends. Lying within the noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you may become distressed, mention this beforehand to your medical team. You may be given a mild sedative to help you relax, and you will usually be offered headphones or earplugs. The MRI scan takes between 30 and 90 minutes.

Radioisotope bone scan

Also called a nuclear medicine bone scan or simply a bone scan, this scan can show if kidney cancer has spread to your bones. These are very rare and used only if you have bone pain or if blood tests show high levels of alkaline phosphatase. If cancer is found in the bones, the scan can also be used to check how the cancer is responding to treatment.

Before the scan, a tiny amount of a radioactive substance is injected into a vein. The substance collects in areas of abnormal bone growth. You will need to wait for a few hours while it moves through your bloodstream to your bones. Your body will be scanned with a machine that detects radiation. A larger amount of the substance will usually show up in any areas of bone with cancer cells.

Radioisotope bone scans generally do not cause any side effects. After the scan, you need to drink plenty of fluids to help remove the radioactive substance from your body through your urine. After your scan, you should avoid contact with young children and pregnant women for the rest of the day. Your treatment team will discuss these precautions with you.

PET scan

A PET (positron emission tomography) scan is a specialised imaging test. A small amount of radioactive solution is used to help cancer cells show up brighter on the scan. Kidney cancer does not always show up well on a standard PET scan, however, newer radioactive solutions to use with PET are being developed.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to contrast during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or other kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Looking inside your bladder, ureters or kidneys

If you have blood in your urine, your doctor might use a thin tube with a light and camera to look inside your bladder (cystoscopy), ureters (ureteroscopy) or kidneys (pyeloscopy).

You will have an anaesthetic before these procedures. This will usually be a local anaesthetic for a cystoscopy and a general anaesthetic before a ureteroscopy or pyeloscopy.

For a few days after these tests you may see some blood in your urine and feel mild discomfort when urinating. These procedures help rule out urothelial carcinoma, which can start in the bladder, a ureter or part of the kidney. They may not be needed if imaging scans have found a kidney tumour.

Tissue biopsy

A biopsy is when doctors remove a sample of cells or tissue from an area of the body. It is a common way to diagnose cancer, but it is not always needed for kidney cancer before treatment. For many people with kidney cancer, the main treatment is surgery. In this case, the tissue removed during surgery is tested to confirm that it is cancer.

A biopsy may be done before treatment when:

- it is uncertain if the tumour is cancerous or benign

- non-surgical treatment approaches (such as ablative therapy, active surveillance or radiation therapy) are recommended – a biopsy will help work out what other treatment is needed

- it appears that the cancer has spread beyond the kidney and a biopsy could help guide the choice of drug therapies.

If a biopsy is done, it will be a core needle biopsy. You will have a local anaesthetic to numb the area, and then an interventional radiologist will put a hollow needle through the skin. They will use an ultrasound or CT scan to guide the needle to the kidney and remove a sample of tissue. The procedure usually takes about 30 minutes but you may need to rest for a few hours before you can go home. You may also have some discomfort or notice some blood in your urine.

The tissue sample will be sent to a laboratory, and a specialist doctor called a pathologist will look at the sample under a microscope to check for any cell changes.

In some cases, a kidney tumour will turn out to be benign (not cancer). Small benign kidney growths, including oncocytoma and angiomyolipoma, may not need treatment. If they do, it may be similar to the treatment for early kidney cancer.

Grading kidney cancer

By examining a sample of kidney tissue, doctors can see how similar the cancer cells look to normal cells and estimate how fast the cancer is likely to grow. This is called grading.

Grading helps the doctors decide what follow-up treatment you might need and whether to consider a clinical trial.

In Australia, both the Fuhrman system and the newer International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) system may be used to grade kidney cancer.

Both systems grade kidney cancer from 1 to 4, with grade 1 the lowest and grade 4 the highest. As the grade increases, the cancer cells look less similar to normal cells. Higher-grade cancers tend to be more aggressive than lower-grade cancers.

Staging kidney cancer

The stage of a cancer describes how large it is, where it is, and whether it has spread beyond the kidney. Knowing the stage of the kidney cancer helps doctors plan the best treatment for you.

The stage can be given before surgery (clinical staging), but may be revised after surgery (pathologic staging).

If you have kidney cancer, your doctor will use the results of the tests completed to assign a stage of 1 to 4:

- stages 1–2 are considered early kidney cancer

- stages 3–4 are considered advanced kidney cancer.

How kidney cancer is staged

The most common staging system for kidney cancer is the TNM system, which stands for tumour–nodes–metastasis. This system gives numbers to the size of the tumour (T1–4), whether or not lymph nodes are affected (N0 or N1), and whether the cancer has spread or metastasised (M0 or M1). Based on the TNM numbers, the doctor then works out the cancer’s overall stage (1–4).

|

stage 1 - early |

The cancer is found in the kidney only and measures less than 7 cm. |

|

stage 2 - early |

The cancer is larger than 7 cm, but has not spread outside the kidney. |

|

stage 3 - locally advanced |

The cancer is any size and has spread to the major kidney veins, into the fat around the kidney, or to nearby lymph nodes. |

|

stage 4 - advanced (metastatic) |

The cancer has spread to surrounding tissue outside the kidney, to the adrenal gland or to more distant parts of the body (such as the distant lymph nodes, the liver, lungs, bone or brain). |

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease. Your doctor can give you an idea about common issues that affect people with kidney cancer.

The stage of the cancer is the main factor in working out prognosis. In most cases, the earlier that kidney cancer is diagnosed, the better the chance of successful treatment. If the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, it is very unlikely that all of the cancer can be removed, but treatment can often keep it under control for some time.

People who can have surgery to remove kidney cancer tend to have better outcomes. Other factors such as your age, general fitness and medical history also affect prognosis.

Treatment for early kidney cancer

Early kidney cancer (stage 1 or 2) is localised. That means the cancer is found in the kidney only.

The main treatment for early kidney cancer is surgery.

Less often, thermal ablation, cryotherapy and stereotactic body radiation therapy are used. Sometimes the best approach for early kidney cancer is to watch the cancer over time.

Preparing for treatment

Talk with your doctors about whether you need to do anything to prepare for treatment and help your recovery.

They may suggest that you exercise, eat a healthy diet or drink less alcohol. You may also find it helpful to talk to a counsellor about how you are feeling.

If you smoke, you will be encouraged to stop. Research shows that quitting smoking before surgery reduces the chance of complications. To work out a plan for quitting, talk to your doctor or call the Quitline on 13 7848.

Preparing for treatment in this way – called prehabilitation – may improve your strength, help you cope with treatment side effects and improve the results of treatment.

Active surveillance

Your doctor may suggest monitoring the cancer closely rather than starting treatment. This approach is known as active surveillance. The aim is to maintain kidney function and avoid unnecessary treatment, while looking for changes that mean treatment should start.

Active surveillance may be suggested if the tumour is less than 4 cm in size. It might also be an option if you are not well enough for surgery and the tumours are small, or if you are older.

Active surveillance involves having regular ultrasounds or CT scans. If these imaging tests suggest that the tumour has grown, you may be offered active treatment (usually surgery). Ask your doctor how often you need check-ups.

Choosing active surveillance avoids treatment side effects, but you might feel anxious about having a cancer diagnosis without active treatment. Talk to your doctors about ways to manage any worries. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for early kidney cancer.

Depending on the type of kidney cancer, the grade and stage of the cancer, and your general health, you might have surgery to remove part or all of a kidney.

Partial nephrectomy

This removes the cancer and a small part of the surrounding tissue, leaving some healthy tissue in the affected kidney. This operation may be recommended for tumours smaller than 7 cm that are in the kidney only. It may also be used for people who have existing kidney disease, cancer in both kidneys, or only one working kidney.

A partial nephrectomy is a more complex operation than a radical nephrectomy. Whether it is possible depends on where the tumour is in the kidney, as well as the expertise of the surgeon and hospital.

Radical nephrectomy

The whole affected kidney, a small part of the ureter and the surrounding fatty tissue are removed. The adrenal gland and nearby lymph nodes might also be removed. This is the most common operation for large tumours.

Sometimes the kidney cancer may have spread into the renal vein and even into the vena cava, the large vein that takes blood to the heart. Even if the cancer has spread to the vena cava, it is sometimes possible to remove all the cancer in one operation.

The remaining kidney – If a whole kidney or part of a kidney is removed, the remaining kidney usually does the work of both kidneys. Your doctor will talk to you about how to keep the remaining kidney healthy, which may include taking steps to reduce your risk of high blood pressure, heart problems and diabetes.

How the surgery is done

If you have surgery for kidney cancer, it will be carried out in hospital. A nephrectomy is a major operation and you will be given drugs (general anaesthetic) to put you to sleep and temporarily block any pain or discomfort during the surgery.

One of the following methods will be used to remove part or all of the kidney (partial or radical nephrectomy). The method recommended for you will depend on the size and location of the tumour and your general health. Your surgeon will talk to you about the risks of the procedure.

Open surgery – This is usually done with a long cut (incision) at the side of your abdomen where the affected kidney is located. In some cases, the incision is made in the front of the abdomen or in another area of the body where the cancer has spread. If you are having a radical nephrectomy, the surgeon will clamp off and divide the major blood vessels and tubes to the affected kidney before removing it.

Keyhole surgery – This is also called minimally invasive surgery or laparoscopic surgery. The surgeon will make a few small cuts in the skin, then insert a tiny instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) into one of the cuts. The surgeon inserts tools into the other cuts to remove the cancerous tissue or kidney, using images from the camera as a guide.

Robot-assisted surgery – This is a type of keyhole surgery performed with help from a robotic system. The surgeon sits at a control panel to see a three-dimensional picture and moves robotic arms that hold the instruments. Robotic surgery has meant that more partial nephrectomies can be performed with keyhole surgery, reducing complications and improving recovery time.

Making decisions about surgery

Talk to your surgeon about the types of surgery suitable for you. Ask about the advantages and disadvantages of each method. There may be extra costs involved for some procedures and they are not all available at every hospital.

Compared to open surgery, both keyhole (laparoscopic) surgery and robot-assisted surgery usually mean a shorter hospital stay, less pain and a faster recovery time. But in some cases, open surgery may be a better option.

What to expect after surgery

After a nephrectomy, you will usually be in hospital for 2–7 days, but it can take 6–12 weeks to fully recover. Your recovery time will depend on the type of surgery you had, your age and general health. Once you are home, you will need to take some precautions.

Drips and tubes – While in hospital, you will be given fluids and medicines through a tube inserted into a vein (intravenous drip). You will also have other temporary tubes to drain waste fluids away from the operation site.

For a few days, you will most likely have a thin flexible tube inserted in your bladder that is attached to a bag to collect urine. This is called a urinary catheter. Knowing how much urine you are passing helps hospital staff monitor how the remaining kidney is working. When the catheter is removed, you will be able to urinate normally again.

Pain relief – You will have some pain and discomfort for several days after kidney surgery. This will be managed with pain medicines. You may be given tablets or injections, or you may have patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), which delivers a measured dose of pain medicine through a drip when you press a button. If you still have pain, let your doctor or nurse know so they can change your medicine as needed.

Blood clots – You will usually have to wear compression stockings to help the blood in your legs circulate and prevent blood clots developing. Depending on your risk of clotting, you may be given daily injections of a blood-thinning medicine.

Moving around – Your health care team will probably encourage you to walk the day after the

surgery. A physiotherapist may show you exercises to do while you are recovering and explain how to move safely. Doing breathing or coughing exercises can help you avoid developing a chest infection.

It will be some weeks before you can lift heavy things, reach your arms overhead or drive. Ask your doctor how long you should wait before attempting any of these activities or returning to work.

Returning home – When you get home, you will need to take things easy and only do what is comfortable. Let your family and friends know that you need to rest a lot and might need some help around the house.

To help your body recover from surgery, try to eat a balanced diet (including proteins including lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, milk, yoghurt, nuts, seeds, and legumes such as beans).

Check-ups – You will need to visit your surgeon for a check-up a few weeks after you’ve returned home. You will usually leave the hospital with the details of your appointment. If you haven’t been given an appointment time, check with your surgeon’s rooms.

Other treatments

If surgery is not the best approach, other treatments may be recommended to destroy or control early kidney cancer.

Thermal ablation

This procedure uses heat to destroy small tumours. The heat may come from radio waves (radiofrequency ablation or RFA) or microwaves (microwave ablation or MWA). The heat kills the cancer cells and forms internal scar tissue. The doctor inserts a fine needle into the tumour through the skin, using a CT scan as a guide. The needle delivers either radio waves or microwaves into the tumour.

Thermal ablation is usually done under general anaesthetic in the x-ray department or the operating theatre. The procedure itself takes about 15 minutes and you can usually go home after a few hours. Side effects, including pain or fever, can be managed with medicines.

Cryotherapy

Also known as cryosurgery, cryotherapy kills cancer cells by freezing them. Under a general or spinal anaesthetic, a cut is made in the abdomen and multiple probes are inserted into the tumour. The probes get very cold, which freezes and kills the cancer cells. Cryotherapy takes about 60 minutes. You may have some bleeding and discomfort afterwards.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

This specialised form of radiation therapy is also called stereotactic ablative body radiation therapy (SABR). It is a way of giving a highly focused dose of radiation therapy to an early kidney cancer when surgery is not possible. If you have SBRT, you will lie on a treatment table under a machine that directs radiation beams from outside the body to the kidney. SBRT is painless and is usually delivered over 1–3 days.

Treatment for advanced kidney cancer

When kidney cancer has invaded the major kidney veins or spread to nearby lymph nodes (stage 3 or locally advanced), you may still be able to have surgery to remove the tumour.

If kidney cancer has spread outside the kidney to other parts of the body (stage 4 or metastatic), treatment usually aims to slow the spread of the cancer and to manage any symptoms.

A combination of different treatments may be recommended. Which combination is suitable for you will depend on several things, including how soon after diagnosis you start drug therapies, as well as your blood counts, blood calcium levels and general health.

Active surveillance

In some cases, kidney cancer grows so slowly that it won’t cause any problems for a long time. Because of this, especially if the advanced kidney cancer has been found unexpectedly, your doctor may suggest looking at the cancer regularly, usually with CT scans. This approach is known as active surveillance.

If the cancer starts to grow quickly or cause symptoms, your doctor may recommend active treatment.

Speaking to a counsellor about your feelings and individual situation can be helpful. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to talk to a health professional about your concerns.

Having drug therapies

Drugs can reach cancer cells throughout the body. This is called systemic treatment.

Controlling kidney cancer – Targeted therapy and immunotherapy are the main types of drug therapies used to control advanced kidney cancer. Chemotherapy is rarely used for kidney cancer these days. The types of drugs and combinations used are rapidly changing as clinical trials show better responses and improved survival with newer drugs.

Accessing new drugs – Talk with your doctor about the latest developments and whether you are a suitable candidate for any new drug treatments. You may also be able to get other drugs through clinical trials.

Cost of drugs – The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidises the cost of some targeted therapy or immunotherapy drugs as long as certain criteria are met. Medicines or treatments that are not on the PBS are usually very expensive unless given as part of a clinical trial.

Reporting side effects – Your doctors will explain the possible side effects of the different drugs. It is important to tell your treatment team about any side effects you have from drug therapies. Side effects can be better managed when they are reported early. If left untreated, some can become life-threatening.

Managing side effects of drug therapies

Your doctor may be able to prescribe medicine to prevent or reduce side effects of targeted

therapy and immunotherapy drugs. In some cases, your doctor may delay treatment or reduce the dose to lessen side effects.

Listen to our podcast episode ‘New Cancer Treatments – Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy’

Targeted therapy

This is a type of drug treatment that attacks specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Targeted therapy drugs are used as the first treatment for advanced kidney cancer (first-line treatment), often in combination with immunotherapy drugs.

These drugs are usually taken daily as tablets. They may be taken for many months and sometimes even years. There are different drugs available and your medical oncologist will discuss which combination of drugs is best for your situation.

Cancer cells often stop responding to targeted therapy drugs over time. If the first-line treatment stops working, your oncologist may suggest trying another targeted therapy or an immunotherapy drug.

Side effects of targeted therapy

The side effects of targeted therapy will vary depending on the drug used. Common side effects include fatigue, skin rash, mouth sores, nausea, diarrhoea, joint pain and high blood pressure.

Immunotherapy

There have been many advances in treating advanced kidney cancer with immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors. These use the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

Checkpoint inhibitors may be used at different stages of advanced kidney cancer:

- as the first-line treatment for advanced kidney cancer, either on their own or in combination with targeted therapy drugs

- as a second-line treatment when targeted therapy has stopped working

- as long-term treatment to try to control the cancer’s growth (maintenance treatment).

The drugs are usually given into a vein through a drip (intravenously) and the treatment is repeated every 2–6 weeks. How many infusions you have depends on how you respond to the drug and whether you have any side effects. You may keep having the drugs for many months and sometimes even years.

The drugs used for kidney cancer are rapidly changing as clinical trials test newer drugs. Your medical oncologist will discuss which combination of drugs is best for your situation.

Side effects of immunotherapy

The side effects of immunotherapy can vary – not everyone will react in the same way. Immunotherapy can cause inflammation in any of the organs of the body. This can cause side effects such as fatigue, skin rash, joint pain and diarrhoea.

The inflammation can lead to more serious side effects in some people, but this will be monitored closely and managed quickly.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. Conventional external beam radiation therapy may be used if you are not able to have surgery. It may also be used in advanced kidney cancer to shrink a tumour and relieve symptoms such as pain and bleeding (palliative treatment).

Some people may have stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to treat tumours that have spread. This may be offered when the cancer has spread to only a few places outside the kidney.

If you have radiation therapy, you will lie on a treatment table under a machine called a linear accelerator. The machine directs radiation beams from outside the body to the kidney. The treatment is painless and takes only a few minutes.

The total number of treatment sessions depends on your situation. Each session usually lasts for 10–20 minutes. You will be able to go home once the session is over, and in most cases you can drive afterwards.

Side effects – You might have some temporary side effects, such as fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, diarrhoea, tiredness and skin irritation. The radiation oncologist can talk to you about possible side effects and ways to manage them.

Surgery

Surgery to remove kidney cancer that has spread is known as cytoreductive surgery. Generally, surgery is not recommended if you are unwell or if the cancer has spread to many places in the body.

Two types of cytoreductive surgery may be possible in some situations:

- nephrectomy – to remove the primary cancer in the kidney. This may be offered when the kidney cancer is causing symptoms or when there is very little cancer spread outside the kidney. It can also be used in some people who have responded well to systemic treatment

- metastasectomy – to remove some or all of the tumours that have spread. This may be offered when the cancer has spread to only a few places outside the kidney.

Palliative treatment

In some cases of advanced kidney cancer, the medical team may talk to you about palliative treatment. This is treatment that aims to slow the spread of cancer and relieve symptoms without trying to cure the disease. You might think that palliative treatment is only for people at the end of their life, but it may help at any stage of advanced cancer. It is about living for as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

Treatments given palliatively for advanced kidney cancer may include radiation therapy, arterial embolisation (a procedure that can reduce blood in the urine by blocking the blood supply to the tumour), targeted therapy or immunotherapy.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, practical, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The team also provides support to families and carers.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had kidney cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment for early kidney cancer, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. During these check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination and you may have ultrasounds, CT scans or blood tests. Your doctor will talk to you about the follow-up schedule, which will depend on the risk of the cancer coming back.

If you have advanced kidney cancer, you will have appointments with your treatment team on an ongoing basis.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people find that they think more about the cancer and may feel anxious. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people, kidney cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. It is important to have regular check-ups, so that if cancer does come back, it can be found early. If the cancer recurs in the kidney (after a partial nephrectomy), you may be offered more surgery. If the cancer has spread beyond the kidney, your doctor may suggest targeted therapy, immunotherapy or radiation therapy, or occasionally, surgery.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.