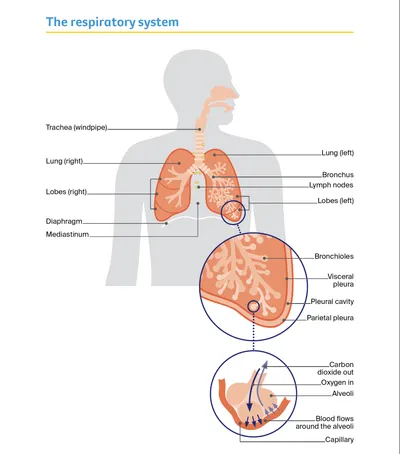

The lungs

The lungs are 2 sponge-like organs that are used for breathing.

They are part of the respiratory system, which also includes the nose, mouth, trachea (windpipe) and airways (tubes) to each lung. There are large airways known as bronchi (singular: bronchus) and small airways called bronchioles. The lungs sit in the chest and are protected by the rib cage.

Lobes – Each lung is made up of sections called lobes – the left lung has 2 lobes, and the right lung has 3 lobes.

Diaphragm – The lungs rest on the diaphragm, which is a wide, thin muscle that helps with breathing, and separates the chest from the abdomen (belly).

Mediastinum – The space between the lungs is called the mediastinum. A number of important structures lie in this space, including:

- the heart and large blood vessels

- the trachea – the tube that carries air into the lungs

- the oesophagus – the tube that carries food to the stomach

- lymph nodes – small, bean-shaped structures that collect and destroy bacteria and viruses.

Pleura – The lungs are covered by 2 thin layers of tissue called the pleura. The inner layer (visceral pleura) lines the lung surface, and the outer layer (parietal pleura) lines the chest wall, mediastinum and diaphragm. The layers are separated by a small amount of fluid that lets them smoothly slide over each other when you breathe. The pleural cavity is the potential space between the 2 layers; there is no space between the layers when the lungs are healthy.

How breathing works

When you breathe in (inhale), your diaphragm moves down and air goes down the trachea and into the bronchi and bronchioles. When the inhaled air reaches the tiny air sacs called alveoli, oxygen passes through the small blood vessels (capillaries) and into the blood. When you breathe out (exhale), your diaphragm relaxes and moves back up, and a waste gas called carbon dioxide is removed from the body and released into the air.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about lung cancer are below.

What is lung cancer?

Lung cancer begins when abnormal cells grow and multiply in an uncontrolled way in the lungs. Cancer that starts in the lungs is called primary lung cancer. It can spread throughout the lungs, and to the lymph nodes, pleura, brain, adrenal glands, liver and bones. When cancer spreads to the lungs from another part of the body (e.g. breast or bowel), this is known as secondary or metastatic lung cancer. This information is about primary lung cancer only.

What are the different types?

There are 2 main types of primary lung cancer: non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

NSCLCs (about 85% of lung cancers) may be classified as:

- adenocarcinoma – begins in mucus-producing cells; more often found in outer part of the lungs

- squamous cell carcinoma – begins in thin, flat cells; most often found in larger airways

- large cell undifferentiated carcinoma – the cancer cells are not clearly squamous or adenocarcinoma.

Other, rarer types of non-small cell lung cancer are adenosquamous carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, salivary gland carcinoma and carcinoid tumours.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

SCLCs (about 15% of lung cancers) tend to start in the middle of the lungs and usually spread faster than NSCLCs.

Pleural mesothelioma is a type of cancer that affects the covering of the lung (the pleura). It is different from lung cancer and is usually caused by exposure to asbestos. Other types of cancer, like cancers that start in the chest wall, and lung diseases such as silicosis may also affect the lungs and have similar symptoms but are not considered lung cancer.

What are the risk factors?

A risk factor is anything that increases a person’s chances of developing a certain condition, such as cancer. It is possible to avoid or reduce the impact of some risk factors. Some people develop lung cancer without having any risk factors. The following factors are known to increase the risk of lung cancer. This does not mean you will develop lung cancer, but if you are concerned, talk to your doctor.

Tobacco smoking factors

Most cases of lung cancer are caused by tobacco smoking. The earlier a person starts smoking, the longer they smoke and the more they smoke, the higher their risk of developing lung cancer.

People who have never smoked can also get lung cancer. About 15% of cases occur in men who have never smoked, and about 30% of cases occur in women who have never smoked.

Environmental or work-related factors

Second-hand smoke – Breathing in other people’s tobacco smoke (second-hand smoke) may cause lung cancer. Living with someone who smokes is estimated to increase the risk of lung cancer by up to 30% in people who don’t smoke.

Exposure to asbestos – People who are exposed to asbestos are more likely to develop lung cancer or pleural mesothelioma. Although the use of asbestos in building materials has been banned in Australia since 2004, asbestos may still be found in some older buildings and fences.

Exposure to other elements – People who have been exposed to radioactive gas (radon), such as uranium miners, have an increased risk of lung cancer. Outdoor and indoor air pollution (e.g. exposure to household air pollution from gas, oil, or wood-burning cooking or heating) is another risk factor. Contact with the processing of arsenic, cadmium, steel and nickel, and exposure to diesel engine exhaust and welding fumes while working may also be risk factors.

Working with materials containing crystalline silica (e.g. stone, sand, rock, bricks, tiles, concrete, artificial stone) can generate silica dust, which may cause a lung disease called silicosis when breathed in and is a risk factor for lung cancer. The use of engineered stone has been banned in Australia since July 2024.

Personal factors

Older age – Lung cancer is diagnosed mostly in people aged over 60 years, although it can occur in younger people.

Family history – You may be at a slightly higher risk if a family member has been diagnosed with lung cancer.

Other conditions – Having another lung disease – lung fibrosis, chronic bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, emphysema or COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) – or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may increase the risk of lung cancer.

How common is lung cancer?

About 15,000 Australians are diagnosed with lung cancer each year. The average age at diagnosis is around 72 years. More men than women develop lung cancer, but since the early 1980s rates have been steadily decreasing among men and increasing among women.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptoms of lung cancer are:

- a new cough that lasts more than 3 weeks, or a cough you have had for a long time that gets worse

- breathlessness or wheezing

- pain in the chest or shoulder

- a chest infection that is recurring or lasts more than 3 weeks

- coughing or spitting up blood.

Lung cancer may also cause other and more general symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, hoarse voice, difficulty swallowing, abdominal (belly) pain, joint pain, neck or face swelling, sweats, and enlarged fingertips (finger clubbing).

Having any of these symptoms does not necessarily mean that you have lung cancer; they may be caused by other conditions or from other effects of smoking. Sometimes, there are no symptoms and the cancer is found during routine tests for other conditions. If you have symptoms, see your doctor without delay.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your general practitioner (GP) will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist called a respiratory physician. The specialist will arrange further tests. If lung cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

- GP – assists you with treatment decisions and works in partnership with your specialists in providing ongoing care

- Respiratory physician – diagnoses diseases of the lungs, including cancer, and recommends initial treatment options

- Thoracic surgeon – diagnoses and performs surgery for cancer and other diseases of the lungs and chest (thorax)

- Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

- Radiation therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy

- Radiologist, nuclear medicine specialist – analyse x-rays and scans; an interventional radiologist may also perform a biopsy under ultrasound or CT, and deliver some treatments; a nuclear medicine specialist coordinates the delivery of nuclear scans such as PET–CT

- Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (also known as systemic treatments)

- Cancer care coordinator or lung cancer nurse coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT, refers you to allied health professionals, provides education and information, and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

- Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

- Psychologist, counsellor – help you understand and manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

- Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

- Speech pathologist – helps with communication, speech and swallowing problems from the cancer, or after treatment

- Social worker – links you to support services and helps with emotional, practical and financial problems

- Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume your usual activities

- Physiotherapist, exercise physiologist – help to maintain and restore movement and mobility

before and after treatment, and improve fitness and wellbeing - Palliative care specialists and nurses – work closely with the GP and cancer team to help control symptoms and maintain your quality of life and keep you comfortable and well looked after at end of life

How is lung cancer diagnosed?

Your doctors will arrange several tests to make a diagnosis and work out whether the cancer is in the lung only or has spread beyond the lung.

The test results will help them recommend a treatment plan for you.

Initial tests

The first test is usually a chest x-ray, which is often followed by a CT scan. You may also have a breathing test to check how your lungs are working and blood tests to check your overall health.

Chest x-ray

A chest x-ray is painless and can show tumours 1 cm wide or larger. Small tumours may not show up or may be hidden by other organs.

CT scan

A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-ray beams to create detailed, cross-sectional pictures of the inside of your body. This scan can detect smaller tumours than those found by chest x-rays. It provides information about the tumour, the lymph nodes and other organs. CT scans are usually done at a hospital or radiology clinic. You may be asked to fast (not eat or drink) for several hours before having the scan.

Immediately before the scan, a liquid dye is injected into a vein. This dye is known as contrast, and it makes the pictures clearer. The contrast may make you feel hot all over and leave a bitter taste in your mouth, and you may have nausea (feel sick) or feel a sudden urge to pass urine (pee or wee). These sensations should go away quickly, but tell your doctor if you continue to feel unwell.

The CT scanner is a large, doughnut-shaped machine. You lie still on a table while the scanner moves around you. Getting ready for the scan can take 10–30 minutes, but the scan itself takes only a few minutes and is painless. A low-dose CT scan, which uses less radiation, has been shown to find lung cancer in people with no signs or symptoms.

In July 2025, the Australian Government is introducing a national lung cancer screening program (NLCSP) using low-dose CT scans. It is for people aged 50–70 years old who have smoked at least 20 cigarettes a day for 30 years (or the equivalent, e.g. 40 cigarettes a day for 15 years), and smokers who have quit in the last 10 years. Talk to your GP or call Cancer Council

13 11 20 for updates on this screening program.

Lung function test (spirometry)

This test checks how well the lungs are working. It measures how much air the lungs can hold and how quickly the lungs can be filled with air and then emptied.

For a lung function test, you will be asked to take a full breath in and then blow out into a machine called a spirometer. You may also have a lung function test before you have surgery or radiation therapy.

Blood tests

A sample of your blood will be tested to check the number of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets (full blood count), and to see how well your kidneys and liver are working.

Tests to confirm diagnosis

If a tumour is suspected after a chest x-ray or CT scan, you will need further tests to work out if it is lung cancer.

FDG PET–CT scan

This scan combines a PET (positron emission tomography) scan, with a CT scan in one machine.

As well as helping with the diagnosis, a PET scan can provide detailed information about any cancer that is found.

First, a small amount of safe radioactive glucose solution called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is injected into a vein, usually in your arm. You will be asked to sit or lie quietly for 30–90 minutes while the glucose solution travels around your body. Then you will lie on a table that moves through the scanning machine very slowly. The scan will take about 30 minutes.

Cancer cells take up more of the glucose solution than normal cells do, so they show up more brightly on the scan.

Sometimes a PET scan is done to work out if a biopsy is needed or to help guide the biopsy procedure. You will need to fast (not eat or drink) before having this scan.

Biopsy

The most common way to confirm a lung cancer diagnosis is by biopsy. This is when small sample of tissue is taken from the lung, lymph nodes, or both. The tissue sample is sent to a laboratory, where a specialist doctor called a pathologist looks at the sample under a microscope. There are various ways to take a biopsy.

A new test known as liquid biopsy involves taking a blood sample and examining it for cancer. Liquid biopsy is still being studied to see how accurate it is, and it is not a routine way to diagnose lung cancer. It could help when a tissue biopsy is not safe to perform.

CT-guided lung biopsy – First, you will be given a local anaesthetic. Then, using a CT scan for guidance, the doctor inserts a needle through the chest wall to remove a small sample of tumour from the outer part of the lungs. You will be monitored for a few hours afterwards. There is a small risk of damaging the lung, but this can be treated if it happens.

Bronchoscopy – The doctor will look inside the large airways (bronchi) using a bronchoscope, a flexible tube with a light and camera.

A bronchoscopy is usually performed under light sedation, so you will be awake but feel relaxed and drowsy. You’ll also be given a local anaesthetic (a mouth spray or gargle) so you don’t feel any pain during the procedure. The doctor will then pass the bronchoscope into your nose or mouth, down the trachea (windpipe) and into the bronchi.

Samples of cells can be collected from the bronchi using either a “washing” or “brushing” method where fluid is injected into the lung and then removed, or a brush-like instrument is used to remove cells.

"I think the doctors knew I had cancer based on the shadow on my CT scan. But they didn’t tell me right away. I had to wait 2 weeks until I had a bronchoscopy.” JAMES

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) – This is a type of bronchoscopy that allows the doctor to see deeper in the lung using an ultrasound probe. During this test, the doctor may also take cell samples from a tumour, from the outer parts of the lung, or from lymph nodes in the area between your lungs (mediastinum). Samples from the lymph nodes can help to confirm whether or not they are also affected by cancer.

You will have light sedation and local anaesthetic, or a general anaesthetic. The doctor will then put a bronchoscope (a thin tube with a small ultrasound probe on the end) into your mouth. The bronchoscope will be passed down your throat until it reaches the bronchus. The ultrasound probe uses soundwaves to create pictures that show the size and position of a tumour.

After a bronchoscopy, you may have a sore throat or cough up a small amount of blood. These side effects usually pass quickly but tell your medical team how you are feeling so they can monitor you.

Endoscopic ultrasound – Sometimes, an endoscopic ultrasound is used to check whether the lung cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in the mediastinum. In an endoscopic ultrasound, a probe is put into your mouth and down your oesophagus, and a cell sample is taken from the lymph nodes. You do not need any sedation or anaesthetic for EUS.

Mediastinoscopy – This type of biopsy may be done if larger samples from the lymph nodes found in the area between the lungs (mediastinum) are needed. You will have a general anaesthetic, then the surgeon will make a small cut (incision) in the front of your neck and pass a thin tube down the outside of the trachea. You can usually go home on the same day as having a mediastinoscopy, but sometimes you may need to stay overnight in hospital.

Thoracoscopy – If other tests are unable to provide a diagnosis, you may have a thoracoscopy. This uses a thoracoscope – a tube with a light and camera – to look at and take a tissue sample from the lungs or around the outer pleura.

It is usually done under general anaesthetic with a type of keyhole surgery called video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Sometimes a simpler procedure called a medical thoracoscopy can be done as a day procedure with light sedation.

Biopsy of neck lymph nodes – The doctor may take a sample of cells from the lymph nodes in the neck with a thin needle. This is often done by a radiologist using an ultrasound for guidance.

Other biopsies – If there is concern that the cancer may have spread to other organs, such as the liver, different types of biopsies may be done.

Other tests

In some circumstances, such as if you are not well enough for a biopsy, mucus or fluid from your lungs may be checked for abnormal cells.

Sputum cytology – In this test, a sample of mucus from your lungs (called sputum or phlegm) is examined to see if it contains cancer cells.

Sputum contains cells that line the airways, and is not the same as saliva. To collect a sample for this test, you will be asked to cough deeply and forcefully into a small container. You can do this at home in the morning before eating or drinking. The sample can be kept in your fridge until you take it to your doctor, who will send it to a laboratory to check under a microscope.

Pleural tap – Also known as pleurocentesis or thoracentesis, this procedure drains fluid from around the lungs. A pleural tap can help to ease breathlessness, and the fluid can be tested for

cancer cells.

It is mostly done with a local anaesthetic, with the doctor – often a radiologist – using ultrasound to guide the procedure.

Molecular tests

Biopsy samples may be tested for gene changes or specific proteins in the cancer cells (biomarkers). These tests are known as molecular tests and they help work out which immunotherapy and targeted therapy drugs may help treat the cancer.

Gene changes – Genes are found in every cell of the body and are inherited from both parents. If something triggers the genes to change (mutate), cancer may start growing.

A mutation that occurs after you are born (acquired mutation) is not the same thing as abnormal genes that can be inherited from your parents. Most gene changes linked to lung cancer are not inherited. Lung cancers with gene mutations may be treated with a type of drug therapy called targeted therapy.

Proteins – If certain proteins are found in the biopsy sample from an NSCLC, the cancer may respond to immunotherapy. The most common protein tested for is called programmed death ligand-1 (PD–L1) on the surface of the cancer cells.

Further tests

If the tests show that you have lung cancer, you will have further tests to see whether the cancer has spread beyond the lung to other parts of the body or the bones. You may also have a CT or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan of the brain.

If a PET–CT scan is not available or the results are unclear, you may have a CT scan of the abdomen (belly) and pelvis or a bone scan. For more information, talk to your doctor or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Staging lung cancer

The tests described above help show what type of lung cancer you have and how far it has spread. Called staging, this helps your doctors recommend the best treatment for you.

Both NSCLC and SCLC are staged using the TNM (tumour-nodes-metastasis) system, which considers the size of the tumour, whether it has affected lymph nodes and whether it has spread. This information may be combined to give the lung cancer an overall stage of 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 (often written in Roman numerals as I, II, III or IV).

Sometimes, SCLC is staged using a different system in which the cancer is classified as either limited stage or extensive stage.

Staging NSCLC

In the TNM system, each letter is given a number (and sometimes another letter) to show how advanced the cancer is. For example, T1 means the tumour is 1 cm or smaller, while T4 means the tumour is more than 7 cm, or has spread into nearby organs, or there are 2 or more separate tumours in the same lung.

|

stage 1 - early |

The cancer is no bigger than 4 cm and hasn’t spread outside the lung or to any lymph nodes. |

|

stages 2-3 - locally advanced |

The cancer can be any size and may have spread to nearby lymph nodes, other parts of the lung, the airway, or surrounding areas outside the lung. |

|

stage 4 - advanced |

The cancer can be any size. It may have spread to lymph nodes and either to the other lung, to fluid in the pleura around the lungs or the heart, or to another part of the body such as the liver, bones or brain. |

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict exactly how the disease will respond to treatment. Instead, your doctor can give you a general idea of the outlook for people with the same type and stage of lung cancer.

To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- your test results

- the type and stage of lung cancer

- the rate and extent of tumour growth

- other factors such as your age, fitness and overall health, and whether you smoke or vape.

Discussing your prognosis and thinking about the future can be challenging and stressful. It is important to know that although some statistics for lung cancer can be frightening, they are an average and may not apply to your situation. Talk to your doctor about how to interpret any statistics that you come across, as well as the best and worst possible outcomes. This information can help you make treatment decisions.

As in most types of cancer, the outcomes of lung cancer treatment tend to be better when the cancer is found and treated early. Newer drug treatments such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy have given promising results in many people with advanced lung cancer and are bringing hope for a longer, healthier life to those who have lung cancer that has spread.

For certain circumstances, these therapies are now being used for earlier stage lung cancer.

Treatment for lung cancer

Treatment for lung cancer will depend on the type of lung cancer you have, the stage of the cancer, how well you can breathe (your lung function) and your general health.

All treatments chosen for you will be expected to be safe and effective.

Understanding the aim of treatment

For early or locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (stages 1–3 NSCLC) or limited-stage small cell lung cancer (stages 1–3 SCLC), treatment may be given with the aim of making the cancer go away. This is called curative treatment.

Because lung cancer causes vague symptoms or even no symptoms in the early stages, most people are diagnosed when the cancer is advanced (stage 4 NSCLC, stage 4 SCLC or extensive disease). This means the cancer has spread outside the lung to other parts of the body.

When cancer is advanced, the aim of treatment is often to maintain quality of life by controlling the cancer, slowing down its spread and managing any symptoms. This is called palliative treatment.

Sometimes palliative treatment can significantly shrink or control the cancer, helping people to live as fully and as comfortably as possible for many months or years.

NSCLC and SCLC are treated in different ways.

Treatment options by cancer type and stage

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

|

early (stage 1 or 2) |

Usually treated with surgery, and for stage 1, a type of high-dose targeted radiation therapy called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Stage 2 is sometimes treated with chemotherapy or immunotherapy before or after the surgery. |

|

locally advanced (stage 3) |

Can be treated with surgery and chemotherapy, or with radiation therapy and chemotherapy (without surgery). Immunotherapy may also be used. With some gene mutations, targeted therapy is starting to be used. Treatment will depend on where the cancer is in the lung, the number and location of lymph nodes with cancer and whether a surgeon can safely remove all of the visible cancer. |

|

advanced (stage 4) |

Depending on the symptoms, palliative drug treatment (targeted therapy, chemotherapy or immunotherapy), palliative radiation therapy, SBRT, or a combination of treatments may be used. This depends on the cancer cell type, how much the cancer has spread, the symptoms and the molecular test results. |

Staging SCLC

Sometimes, SCLC is staged using a 2-stage system in which the cancer is classified as either limited disease or extensive disease.

|

limited disease (stage 1–3) |

Usually treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy (called chemoradiation). Sometimes, surgery may be used for stage 1 disease. |

|

extensive disease (stage 4) |

Mainly treated with palliative chemotherapy, with or without immunotherapy. Palliative radiation therapy may also be given to the primary cancer in the lung and to other parts of the body where the cancer has spread to help control symptoms such as pain. |

Surgery

People with early NSCLC (stage 1 or 2) will generally be offered surgery to remove the tumour. How much of the lung is removed depends on several factors:

- the location and size of the cancer

- your general wellbeing and fitness

- how your lungs are working (lung function).

Surgery is not suitable for most people with advanced lung cancer.

If there is fluid in the pleural cavity (called pleural effusion) that keeps returning, you may have surgery (pleurodesis) to control this, or need to insert a catheter.

Preparing for treatment

Stop smoking – If you smoke or vape, you will be advised to stop before you start treatment for lung cancer.

Stopping smoking can improve how treatments work and reduce the impact of side effects such as breathlessness. Research shows that stopping smoking before surgery also reduces the chance of complications and can help you recover faster.

To work out a plan for stopping, talk to your doctor, your nurse specialist, or call Quitline on

13 7848 (13 QUIT).

Eat well and exercise – Your health care team may also suggest that you eat healthy foods and exercise before starting lung cancer treatment.

Preparing for treatment in this way is called prehabilitation. It can help you to cope with cancer treatment, recover more quickly and improve your quality of life.

A dietitian, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist can support you to make lifestyle changes. Ask your doctor for a referral.

Types of lung surgery

Surgery for lung cancer may remove all or part of a lung.

Lobectomy – This is the most common type of surgery for lung cancer. In a lobectomy, one of the lobes of the lung (about 30–50% of the lung) is removed.

Pneumonectomy – If the cancer is in more than one lobe of a lung, or near where the airways enter the lung, a pneumonectomy may be done. In this operation, a whole lung is removed. It’s possible to still breathe normally with one lung.

Segmentectomy – For some early-stage lung cancers that are on the edge of the lung, a segmentectomy may be used. In this operation, a small part of the lobe is removed. In cases where a patient is very unwell, however, a wedge resection may be considered. A wedge resection removes only a tiny piece of the lobe.

Removing lymph nodes

During surgery, the lymph nodes near the cancer will also be removed to check whether the cancer has spread. Knowing if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes helps the doctors decide whether you need further treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

How the surgery is done

There are 2 main ways to perform surgery for lung cancer, and both require a general anaesthetic. Each type of surgery has advantages in particular situations – talk to your surgeon about the best option for you.

VATS – Lung cancer surgery can often be done using a keyhole approach. This is known as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). The surgeon will make a few small cuts (incisions) in the chest wall. A tiny video camera and operating instruments are passed through the cuts, and the surgeon performs the operation from outside the chest. A keyhole approach usually means a shorter hospital stay, faster recovery and fewer side effects.

Thoracotomy – If a long cut is made between the ribs in the side of the chest, the operation is called a thoracotomy. This may also be called open surgery. You will need to stay in hospital for 3–7 days.

Sometimes the surgeon may need to change from a VATs approach to a thoracotomy during the surgery.

Many hospitals in Australia have programs to reduce the stress of surgery and improve your recovery. Called enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or fast-track surgical (FTS) programs, they provide information about what to expect each day after surgery.

What to expect after surgery

Exercises for breathlessness – A pulmonary rehabilitation program can help improve breathlessness and reduce the risk of a chest infection. A physiotherapist will show you how to do exercises. To continue rehabilitation after you leave hospital, talk to your surgeon or visit Lung Foundation Australia to find a program near you.

Pain – You may have some pain after surgery but this can be controlled. Ask for pain relief as needed. Managing the pain will allow you to do breathing exercises and help you to recover. Pain will improve when tubes are removed from the chest.

Recovery time – You will probably go home after 3–7 days. It may take 4–8 weeks after VATS or 6–12 weeks after thoracotomy to get back to your usual activities. Walking can help clear your lungs and speed up recovery.

Tubes and drips – Several tubes will be in place after surgery. They will be removed as you recover. A drip in a vein in your arm (intravenous drip) can provide fluid and medicines. Tubes in your chest drain fluid and help your lungs expand; and a tube in your bladder may check how much urine you pass.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses radiation to target and kill cancer cells. This reduces the risk of the cancer growing or spreading. It uses advanced technology to focus the radiation on the cancer and avoid the normal parts of the body. You may be given radiation therapy on its own, or after surgery or chemotherapy, or at the same time as chemotherapy (called chemoradiation). When you have it depends on the stage of the cancer.

Radiation therapy may be recommended to treat the primary tumour in the lung:

- if you are unable to have surgery for stage 1 lung cancer

- if you chose not to have surgery

- where a surgery is not able to be safely done to treat locally advanced (stage 3) NSCLC, or to treat limited-disease SCLC

- after surgery, if there is a risk of microscopic cancer cells left behind.

You may be offered radiation therapy as palliative treatment, to control the primary tumour in the lung or areas where the tumour has spread to, with the aim of relieving pain, breathlessness or other symptoms.

For lung cancer, radiation is usually delivered in the form of x-ray beams from a machine outside the body called a linear accelerator. This is known as external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and can be done as standard EBRT or stereotactic radiation therapy.

Standard EBRT – This is usually given once a day, Monday to Friday; each daily treatment lasts for a few minutes. How many treatments you need will depend on the aim of the treatment. To control symptoms, it’s usually 1–2 weeks. Longer-term control is usually for 3–6 weeks.

Stereotactic radiation therapy – Also called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) or stereotactic ablative body radiation (SABR), this can be given as a single dose or a number of doses. It targets a localised tumour with a very high dose of radiation. SBRT cannot be used safely if tumours are close to other organs, such as the windpipe.

How radiation is done

External beam radiation uses a machine that gives high-dose radiation beams from different angles to precisely target the tumour.

Planning radiation therapy

Before treatment starts, you will have a planning session at the radiation therapy centre to work out the dose and position of the beams. During this session, you will have a CT scan to determine the area to be treated, and small marks will be put on your skin so the radiation therapists ensure your body is in the same position for every treatment. You may have a 4-dimensional CT scan to record any movement of the cancer as you breathe. You may also be shown some breathing exercises to help your breathing stay as regular as possible.

Having radiation therapy

Each treatment day, a radiation therapist will help you lie in the position decided at the planning session. You will have an x-ray to check that the correct area is being treated. When the treatment is being delivered, you will be alone in the room, but the radiation therapists will be able to hear you and talk to you from the monitoring area as there are speakers and a microphone in the room. The radiation treatment itself takes only a few minutes, but a session may last about 20 minutes, depending on how complex the set-up process is.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy itself is painless, but it can affect some tissues and organs of the body. You may experience some side effects during or after radiation therapy, depending on the dose, the number of treatments and the part of the chest treated. Most side effects are temporary and improve a few weeks after treatment.

Fatigue – Feeling tired is common after radiation therapy. You may need more rest or sleep, but gentle exercise and being physically active, if you are able to, is encouraged.

Discomfort when swallowing and heartburn – If the cancer is in the centre of the chest and near the oesophagus, you may find swallowing uncomfortable, and develop heartburn. You may need to eat softer food and avoid hot drinks until you feel better. You may also be prescribed medicine by your radiation oncologist to control the pain until these side effects resolve.

Skin changes – Skin may become red and inflamed if the tumour is very close to the skin, but this is rare. Applying a moisturising cream and sun protection daily can help protect your skin.

Lung inflammation (pneumonitis) – Radiation therapy may cause inflammation of the lungs, called radiation pneumonitis. This may happen 2–12 months after the radiation has finished and usually doesn’t need any treatment. Occasionally, it can cause shortness of breath and/or a cough which may require treatment with steroids. Tell your radiation oncology team about any side effects you are concerned about, as most can be managed.

Drug therapies

Sometimes called systemic therapies, drug therapies can travel throughout the body to treat cancer cells wherever they may be. This can be helpful for cancer that has spread (metastatic cancer). The main types of drug therapies used to treat lung cancer are chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

Having drug therapies

Some drug therapies are given through a vein (intravenously). You will probably have drug therapies as an outpatient, which means you go to a treatment centre, but not stay overnight. Some types of targeted therapy come as tablets and can be taken by mouth (orally) at home.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth. Chemotherapy can be used at different times:

- before surgery to try to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove (neoadjuvant chemotherapy)

- before, or in combination with, radiation therapy to make radiation therapy more effective (chemoradiation); or in combination with immunotherapy

- after surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer returning (adjuvant chemotherapy)

- when cancer is advanced – to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life (palliative chemotherapy).

Chemotherapy given to treat lung cancer is usually one, two or three drugs together or one by itself. Drugs are commonly given as a period of treatment followed by a break to allow your body to recover. This is called a cycle. The number of cycles will depend on the type of lung cancer and any side effects you have.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy works on cells that are dividing rapidly. Cancer cells divide rapidly, as do some healthy cells such as the cells in your blood, mouth, digestive system and hair follicles. Side effects occur when these normal cells are damaged. As the body constantly makes new cells, most side effects are temporary. Some side effects are listed below.

Anaemia – A low red blood cell count is called anaemia. This can make you feel tired, breathless or dizzy. Your treatment team will monitor your red blood cell levels and suggest treatment if necessary

Risk of infections – Chemotherapy drugs can lower the number of white blood cells that fight infections caused by bacteria. This means if you get an infection caused by a virus, such as a cold, flu or COVID-19, the risk of getting a bacterial infection is further increased. Talk to your doctor about being vaccinated against flu and COVID-19. Keeping your hands and mouth clean and social distancing can also help prevent the risk of infection. If you feel unwell or have a temperature above 38°C, call your doctor immediately or go to the hospital emergency department.

Mouth ulcers – Some chemotherapy drugs cause mouth sores, ulcers and thickened saliva, making swallowing difficult. Your treatment team will explain how to prevent these issues and take care of your mouth.

Hair loss – You may lose hair from your head, chest and other areas, depending on the chemotherapy drugs you receive. The hair will grow back after treatment is completed, but the colour and texture may change.

Nausea, vomiting or constipation – You will usually be prescribed anti-nausea medicine with your chemotherapy drugs, but some people still feel sick (nauseous) or vomit. Constipation is also a common side effect of some types of anti-nausea medicines. Let your treatment team know if you have these side effects, as they may be able to give you extra medicines.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Chemotherapy’

Download our fact sheet ‘Mouth Health and Cancer Treatment’

Listen to our podcast episode ‘Appetite Loss and Nausea’

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of drug treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Immunotherapy drugs, also known as immune checkpoint inhibitors, block proteins, such as PD-L1, that stop immune cells from recognising and destroying the cancer cells. Once the proteins are blocked, the immune cells can potentially recognise and attack the lung cancer.

Several checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for most types of advanced NSCLC and for SCLC when it is used together with chemotherapy. Several other checkpoint inhibitors are being tested in clinical trials for lung cancer, including using a combination of these drugs.

Checkpoint inhibitors do not work for all types of lung cancer, but some people have had good results. Ask your oncologist about molecular testing and whether immunotherapy may be right for you.

Immunotherapy may be used alone, or with chemotherapy as a palliative treatment, or after chemoradiation.

Immunotherapy is now being used for some people with stage 2 NSCLC, either before or after surgery. Tell your medical team if you have an autoimmune disease as this might mean this treatment is not suitable.

Side effects of immunotherapy

Immunotherapy can cause an inflammatory response in various parts of the body, which leads to different side effects depending on which part of the body becomes inflamed.

Common side effects include fatigue, rash, diarrhoea and joint pain. Most people have mild side effects that can be treated easily and usually improve.

Let your treatment team know if you have new or worsening side effects. If left untreated, some side effects can become serious and may even be life-threatening. For a detailed list of side effects, visit eviQ.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Immunotherapy’

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of drug treatment that attacks specific features of cancer cells, known as molecular targets, to stop the cancer growing and spreading. The molecular targets are usually particular protein changes that are found in or on the surface of the cancer cells as a result of abnormal genes.

Targeted therapies are currently mostly available for people with NSCLC whose tumours have specific gene changes when the cancer is advanced or has come back after initial surgery or radiation therapy. These drugs will only work if the cancer contains the particular gene targeted and, even then, they do not work for everyone. Ask your oncologist about molecular testing and whether targeted therapy is an option for you.

For some abnormal genes, targeted therapy can be given as tablets or capsules.

This area of cancer treatment is changing rapidly, and it is likely that new gene changes and targeted therapy drugs will continue to be discovered. Talk to your medical oncologist about any clinical trials that may be suitable for you.

Cancer cells often become resistant to targeted therapy drugs over time. If the first-line treatment stops working, your oncologist may suggest trying another targeted therapy drug or another systemic treatment. This is known as second-line treatment.

Side effects of targeted therapy

Although targeted therapy drugs may cause less harm to healthy cells than chemotherapy, they can still have side effects. These side effects vary depending on the type of targeted therapy drugs used. Common side effects include a rash, fatigue, diarrhoea, nausea, body aches or swelling. Vomiting is a rare side effect.

In rare cases, targeted therapy may also cause pneumonitis (inflammation of the lung tissue), which can lead to breathing problems. It is important to report any new or worsening side effects to your treatment team. If left untreated, some side effects can become serious and may even be life-threatening. For a detailed list of side effects, visit eviQ.

Palliative and supportive care

If the cancer is advanced when it is first diagnosed or comes back after treatment (recurrence), your doctor will discuss palliative treatment for any symptoms caused by the cancer. This is also known as supportive care. They may refer you to a palliative care specialist.

Palliative treatment aims to manage symptoms without trying to cure the disease. It can be used at any stage of advanced lung cancer to improve quality of life and does not mean giving up hope. In fact, palliative treatment can help some people with advanced lung cancer to live well and with few symptoms for many months or years.

Ways that symptoms may be relieved include:

- having palliative drug therapies (chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy), radiation therapy and surgery to slow the spread of cancer and control symptoms such as pain or breathlessness

- draining any fluid to help prevent it building up again.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs and those of your family or carer.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Palliative Care’

Download our booklet ‘Living with Advanced Cancer’

Listen to our podcast series ‘The Thing About Advanced Cancer’

Managing symptoms

For many people, lung cancer is diagnosed at an advanced stage. In these cases, the main goal of treatment is to manage symptoms for as long as possible.

This section describes procedures and strategies for managing the most common symptoms of lung cancer. Keep in mind that you won’t necessarily experience every symptom listed here.

Breathlessness

Many people with lung cancer have difficulty breathing before or after diagnosis. This shortness of breath is also called breathlessness or dyspnoea. It can occur for several reasons, including:

- the cancer itself and lungs not working as well

- drop in fitness level due to less physical activity

- build-up of fluid (pleural effusion) in the pleural cavity, the space between the 2 layers of thin tissue covering the lung

- lung tissue changes after radiation therapy (radiation pneumonitis)

- other respiratory conditions, such as COPD.

If the cancer is blocking a main airway, a laser, stent (a metal or plastic tube) or radiation therapy may help open the airway and make breathing easier. You may also be referred to a pulmonary rehabilitation program to learn how to manage breathlessness. This program will include exercise, breathing techniques, ways to clear the airways, and tips for conserving energy. Some people also use supplemental oxygen at home.

If you smoke or vape, your doctor will recommend you quit and suggest ideas for how to do this.

Having a pleural tap

For some people, fluid may build up in the pleural cavity, the space between the 2 layers of thin tissue covering the lung. The build-up of fluid is called pleural effusion. This can put pressure on the lung, making it hard to breathe. Having a pleural tap can relieve this symptom. This procedure is also known as pleurocentesis or thoracentesis.

To drain the fluid, your doctor or radiologist numbs the area with a local anaesthetic and inserts a hollow needle between your ribs into the pleural cavity. It then takes about 30–60 minutes to drain the fluid. You usually don’t have to stay overnight in hospital after a pleural tap. A sample of the fluid is sent to a laboratory for testing.

Ways to control fluid around the lungs

If breathlessness is caused by pleural effusion, you may need to have surgery.

Types of procedures include:

- pleural tap to drain the fluid

- pleurodesis to stop fluid building up again

- an indwelling pleural catheter.

Pleurodesis – Pleurodesis is a way to close the pleural cavity. Your doctors might recommend this procedure if the fluid builds up again after you have had a pleural tap. It may be done by a thoracic surgeon or respiratory physician in one of two ways, depending on how well you are and what you would prefer.

VATS pleurodesis – This method uses a keyhole approach called video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). You will be given a general anaesthetic, then the surgeon will make one or more small cuts in the chest and pass a tiny video camera and operating instruments through.

After all fluid has been drained, the surgeon then injects some sterile talcum powder into the pleural cavity. This causes inflammation that helps stick the 2 layers of the pleura together and prevents fluid from building up again. You will stay in hospital for a few days.

Bedside talc slurry pleurodesis – If you are unable to have a general anaesthetic, a pleurodesis can be done under local anaesthetic. A small cut is made in the chest, then a tube is inserted into the pleural cavity. Fluid can be drained through the tube into a bottle.

Next, sterile talcum powder mixed with salt water (a “slurry”) is injected through the tube into the pleural cavity. Nurses will help you move into various positions every 10 minutes to get the talc slurry to spread throughout the pleural cavity. The process takes about an hour.

A talc slurry pleurodesis usually requires a stay in hospital of 2–3 days. After the procedure, some people feel a burning pain in the chest for 1–2 days, but this can be eased with medicines.

Indwelling pleural catheter – An indwelling pleural catheter is a small soft tube used to drain fluid from around the lungs. It may be offered if fluid keeps building up in the pleural cavity making it hard to breathe, or if you are unable or do not want to have a pleurodesis. The catheter can be in place permanently, or until it is no longer needed.

You will be given a local anaesthetic, then the doctor makes 2 small cuts in the chest wall and inserts the catheter into the pleural cavity. One end of the tube is inside the chest, and the other is coiled and fixed outside your skin with a small dressing.

The fluid can be drained at home. When fluid builds up and needs to be drained (usually once or twice a week), the catheter is connected to a small bottle. A community nurse can drain the fluid for you or they can teach you, a family member or friend how to drain the catheter.

Improving breathlessness at home

It can be distressing to feel short of breath, but several simple strategies can help provide some relief from breathlessness at home.

Treat other conditions – Let your doctor know if you feel breathless. Conditions such as anaemia, a lung infection or COPD may also make you feel short of breath, and these can often be treated.

Sleep more upright – Use a recliner chair or prop yourself up in bed to help you sleep in a more upright position. An occupational therapist may be able to recommend a special pillow for sleeping.

Check if equipment could help – Ask your health care team about equipment to manage breathlessness, such as:

- nebulisers

- incentive spirometers

- oxygen concentrator to use at home

- portable oxygen cylinders for outings.

Relax on a pillow – While seated at a table, rest your head and upper chest on a pillow. Bend from your hips and keep your back straight. This helps to relax your breathing muscles.

Ask about medicines – Talk to your doctor about medicines, such as a low dose of morphine, to ease breathlessness. It is important to keep any chest pain well controlled because pain may prevent you from breathing deeply.

Modify your movement – Do gentle exercise to help you avoid losing strength and muscle. An exercise physiologist, physiotherapist or occupational therapist from your treatment centre can explain how to adjust your activities to improve breathlessness.

Create a breeze – Use a portable or handheld fan to direct a cool stream of air across your face

if you feel short of breath when you are not active. Sitting by an open window can also help.

Find ways to relax – Listen to a relaxation recording or learn other ways to relax. This can help you to control anxiety and breathe more easily. Some people find breathing exercises, acupuncture and meditation helpful.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Pain

Pain can be a symptom of lung cancer and a side effect of treatment. If pain is not controlled, it can affect your quality of life and how you cope with treatments.

There are different ways to control pain. Aside from pain medicines, various procedures can manage any build-up of fluid that is causing pain. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy can reduce pain by shrinking a lung tumour. Surgery may help treat pain from bones: for example, if the cancer has spread to the spine and is pressing on nerves (nerve compression).

Managing pain

- Tell your doctor when you are in pain so they can help you manage it. A palliative care or pain specialist may be able to help with hard- to-manage pain.

- Keep track of your pain in a diary – note what the pain feels like, how intense it is, where it comes from and travels to, how long it lasts and if it goes away with a specific medicine or another therapy such as a heat pack.

- Allow a few days for your body to adjust to the dose of pain medicine and for drowsiness to improve.

- Take pain medicine regularly as prescribed, even when you are not in pain. It’s better to stay

on top of the pain. - Use a laxative regularly to prevent or relieve constipation caused by pain medicines.

- Learn relaxation or meditation techniques to help you cope with pain.

Poor appetite and weight loss

Some people stop feeling interested in eating and lose weight before lung cancer is diagnosed. These symptoms may be caused by the disease itself, or by feeling sick, having difficulty swallowing, being breathless, or feeling down.

Weight loss can affect how your body responds to cancer treatment, your risk of infection, and how quickly you recover. This can happen to anyone, no matter what size. Eating well will help you cope better with treatment and side effects, and improve your quality of life.

Eating when you have little appetite

- Choose high-kilojoule and high-protein foods (e.g. add cheese or cream to meals, use full-cream milk).

- Try eating smaller portions more often (e.g. 5–6 smaller meals per day).

- Avoid drinking fluids at mealtimes, which can fill you up too quickly.

- Eat moist food, such as scrambled eggs, because it is easier to swallow.

- Eat salads or cold foods if hot food smells make you feel sick. Avoid fatty or sugary foods if these make you feel nauseous.

- Add ice-cream or fruit to a drink to increase kilojoules.

- Eat more of your favourite foods – follow your cravings.

- See a dietitian for more tips on what to eat and drink – they can suggest small changes to your diet or what protein drinks or nutritional supplements to use that can help you stay well nourished. To find a dietitian, visit Dietitians Australia.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Fatigue

It is common to feel very tired during or after treatment, and you may not have the energy for day-to-day activities. Cancer-related fatigue is different from tiredness, as it may not go away with rest or sleep. You may also lose interest in things that you usually enjoy doing or have trouble concentrating on one thing for very long.

Let your treatment team know if you are struggling with fatigue. Sometimes fatigue can be caused by a low red blood cell count (anaemia), or be a side effect of drug therapies or a sign of depression, all of which can be treated. There are also many hospital and other programs available to help you manage fatigue.

Managing fatigue

- Set small, manageable goals for the day, and rest before you get too tired.

- Plan breaks throughout the day when you are completely still for a while. An eye pillow can help at these times.

- Accept offers of help from family and friends.

- Ask your doctor about what sort of exercise would be suitable. An exercise physiologist or

physiotherapist can help with safe and appropriate exercise plans. - Get a referral to an occupational therapist for help with relaxation techniques, breathing

exercises and ways to conserve your energy. - Consider acupuncture – some people find it helps with cancer-related fatigue.

- Say no to things you really don’t feel like doing.

Difficulty sleeping

Getting a good night’s sleep is important for maintaining your energy levels, reducing fatigue and improving your mood. Pain, breathlessness, anxiety, depression and some medicines can make it hard to sleep. If you already had sleep problems before the lung cancer diagnosis, these could become worse.

Talk to your doctor about what might help improve your ability to sleep. Your medicines may need adjusting, or sleep medicines may be an option. Talking to a counsellor may help if you are feeling anxious or depressed. Some strategies that people with cancer have found helpful are listed below.

Getting a better night’s sleep

- Try to do some gentle physical activity every day. Exercising may help you to sleep better. An exercise physiologist or physiotherapist can tailor an exercise program for you. See our information about ‘Exercise and Cancer‘

- Avoid alcohol, caffeine, nicotine and spicy food.

- Avoid watching television or looking at a computer, smartphone or tablet before bed, as the blue light may tell your body it’s time to wake up.

- Follow a regular routine before bed and ensure the room is dark, quiet and a comfortable temperature.

- Try soothing music, a recording of rain sounds, or a relaxation recording.

Living with lung cancer

Life after a diagnosis of lung cancer can present many challenges.

It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes. Establish a daily routine that suits you and the symptoms you’re coping with and talk to your health care team about any concerns. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust. They might benefit from reading the information on these pages.

For some people, the cancer goes away with treatment. Other people will have ongoing treatment to manage symptoms. You are likely to feel a range of emotions about having lung cancer. Talk to your treatment team if you are finding it hard to manage your emotions. Cancer Council 13 11 20 can also provide you with some strategies for coping with the emotional and practical aspects of living with lung cancer.

Follow-up appointments

Whether treatment ends or is ongoing, you will have regular appointments to manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. During these check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination and you may have chest x-rays, CT scans and blood tests. You will also be able to discuss how you’re feeling and mention any concerns you may have.

Check-ups after treatment usually happen every 3–6 months for the first couple of years and every 6–12 months for the following 3 years. When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people feel anxious (“scananxiety”). Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people, lung cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. Lung cancer is more likely to recur in the first 5 years after diagnosis. If the cancer returns, your doctor will discuss treatment options with you. These will depend on the type of lung cancer, where the cancer has recurred, and the stage and grade.

Whichever treatment you are given or choose to have, support from palliative care specialists and nurses can help you manage symptoms. Talk to your doctor about how to get this support.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Palliative Care’

Listen to our podcast series ‘The Thing About Advanced Cancer’

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.