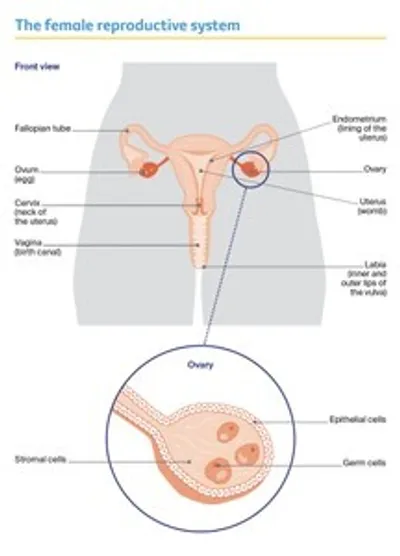

The ovaries

The ovaries are part of the female reproductive system, which also includes the fallopian tubes, uterus (womb), cervix (the neck of the uterus), vagina (birth canal) and vulva (external genitals).

Ovaries are made up of:

- epithelial cells – found on the outside

- germ (germinal) cells – inside, these mature into eggs

- stromal cells – forming connective tissue and making hormones.

What the ovaries do – The ovaries produce eggs. They also make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone, which control the release of eggs (ovulation) and the timing of periods (menstruation).

Shape and position in the body – The ovaries are 2 small, walnut shaped organs. They are found in the lower part of the abdomen (belly). There is one ovary on each side of the uterus, close to the end of each fallopian tube.

Ovulation and menstruation – During ovulation, from puberty through to menopause, one ovary – or occasionally both – releases an egg. The egg travels through the fallopian tube to the uterus. If a pregnancy does not occur, some of the lining of the uterus is shed and flows out of the body. This flow is called a period or menstruation.

Menopause – As you get older, the ovaries gradually make less oestrogen and progesterone. When levels of these hormones fall low enough, periods stop. This is known as menopause. After menopause, you can’t have a child naturally.

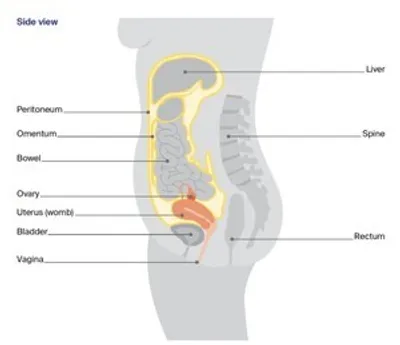

Organs and structures near the ovaries

Other organs and structures near the ovaries include the:

- bladder – stores urine (pee)

- bowel – helps the body break down food

- rectum – stores faeces (poo)

- peritoneum – lining of the abdomen

- omentum – a curtain of fatty tissue that hangs in front of the large bowel like an apron.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about ovarian cancer are below.

What is ovarian cancer?

Ovarian cancer starts when cells in one or both ovaries, the fallopian tubes or the peritoneum become abnormal, grow out of control and can form a lump called a tumour. Cancer of the fallopian tube was once thought to be rare, but research suggests that many ovarian cancers start in the fallopian tubes.

If ovarian cancer spreads from the ovaries, it is often to the organs in the abdomen and pelvis. It is common in some types of ovarian cancer for a large amount of fluid to build up in the abdomen (belly).

Sometimes an ovarian tumour is diagnosed as a borderline tumour (also known as a low malignant potential tumour). This tumour is not considered to be cancer but can still spread within the abdomen.

How common is it?

Each year, about 1785 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australia. This includes cancers of the fallopian tube. More than 8 out of 10 women diagnosed are over the age of 50, but ovarian cancer can occur at any age. It is the 9th most common cancer in females in Australia.

Ovarian cancer mostly affects women, but anyone with ovaries can get it. Transgender men and intersex people can also get ovarian cancer if they have ovaries. For information specific to you, speak to your doctor.

What are the different types of ovarian cancer?

There are many types of ovarian cancer. The 3 main types start in different cells found in the ovary.

Epithelial cell

- the most common type of ovarian cancer (about 9 out of 10 cases)

- starts on the surface layer (epithelium) of the ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum

- the most common subtypes include serous, endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous

- serous is the most common subtype; it’s divided into high grade and low grade

- mostly occurs over the age of 60

Stromal cell (or sex cord-stromal tumours)

- rare cancer (about 1 in 10 cases)

- starts in the cells that form the connective tissue in the ovaries and make the hormones oestrogen and progesterone

- may produce extra hormones, such as oestrogen

- usually occurs between the ages of 40 and 60

Germ cell

- rare type of ovarian cancer (less than 1 in 10 cases)

- starts in the egg-producing (germinal) cells found inside the ovary

- usually occurs under the age of 40

Non-cancerous ovarian tumour

Borderline tumour

- abnormal cells that form in the tissue covering the ovary

- doesn’t grow into the supportive tissue (stroma)

- grows slowly

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of ovarian cancer can be similar to other common conditions. This can make it difficult to diagnose early.

Symptoms are more likely to develop as the cancer grows and may include:

- pressure, pain or discomfort in the abdomen or pelvis

- a swollen or bloated abdomen

- appetite changes (e.g. not feeling like eating, feeling full quickly)

- changes in toilet habits (e.g. constipation, diarrhoea, passing urine more often, increased wind)

- indigestion and feeling sick (nausea)

- feeling very tired

- unexplained weight loss or weight gain

- changes to periods such as heavy or irregular bleeding, or vaginal bleeding after menopause

- pain when having sex.

If you have any of these symptoms and they are new for you, are severe or continue for more than 2–3 weeks, it is best to have a check-up. Keep a note of how often the symptoms occur and make an appointment to see your general practitioner (GP).

Ovarian Cancer Australia has produced a symptom diary. You can also use it to record your symptoms and help talk about your concerns with your doctor.

What are the risk factors?

The causes of ovarian cancer are largely unknown, but things that can increase the risk of developing ovarian cancer include:

- age – ovarian cancer is most common over the age of 50 after periods have stopped. The risk increases with age

- genetic factors – up to 1 in 5 serous ovarian cancers (the most common subtype) are linked to an inherited faulty gene, and a smaller proportion of other types of ovarian cancer are also related to genetic faults

- family history – having close blood relatives (e.g. mother, sister) diagnosed with ovarian, uterine, breast, bowel or uterine cancers, or having Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry can increase risk

- endometriosis – this is a condition caused by tissue from the lining of the uterus growing outside the uterus

- reproductive history – women who have not had children, who have had assisted reproduction (e.g. in-vitro fertilisation or IVF), or who have had children after the age of 35 may be slightly more at risk

- lifestyle factors – some types of ovarian cancer have been linked to smoking or carrying extra weight

- hormonal factors – for example, early puberty or late menopause. Some studies have suggested that menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) – formerly called hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – may slightly increase the risk of ovarian cancer if taken for 5 years or more, but the risk is very low.

Some factors may reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer. These include having children before the age of 35; breastfeeding; using the combined oral contraceptive pill for several years; and having your fallopian tubes tied (tubal ligation) or removed.

Does ovarian cancer run in families?

Ovarian cancer most often occurs for unknown reasons but some cases are due to an inherited faulty gene. Having an inherited faulty gene does not mean you will develop ovarian cancer, and you can inherit a faulty gene without a history of cancer in your family.

About 15% of women with ovarian cancer have an inherited fault in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes or other similar genes. The BRCA gene faults can also increase the risk of developing breast cancer and fallopian tube cancer.

Less commonly, a group of gene faults known as Lynch syndrome is associated with ovarian cancer and can also increase the risk of developing cancer of the bowel or uterus.

As other genetic conditions are discovered, they may be included in genetic tests for cancer risk.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your GP will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist called a gynaecological oncologist. The specialist will arrange further tests.

If ovarian cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Health professionals you may see

Gynaecological oncologist – diagnoses and performs surgery for cancers of the female reproductive system (ovarian, cervical, uterine, vulvar and vaginal cancers) and oversees your care

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy and targeted therapy (systemic treatment)

Fertility specialist – diagnoses, treats and manages infertility; may be an obstetrician, gynaecologist or reproductive endocrinologist

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Radiation therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy

Radiologist – analyses and interprets diagnostic scans, such as x-rays and CT and PET–CT scans

Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical

nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

Women’s health physiotherapist – assists with physical problems associated with gynaecological cancers, such as bladder and bowel issues, sexual issues and pelvic pain

Exercise physiologist – prescribes exercise to help people with medical conditions improve their overall health, fitness, strength and energy levels

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Psychologist, counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Lymphoedema practitioner – educates people about lymphoedema prevention and management, and provides treatment if lymphoedema occurs; often a physiotherapist or

occupational therapist

Cancer genetics specialist, genetic counsellor – provide advice about genetic causes of ovarian cancer; arrange genetic tests if required and interpret the results for you and your family

How is ovarian cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor suspects you have ovarian cancer, they will usually start with a pelvic examination, and then order some tests and scans.

The only way to confirm ovarian cancer is through a biopsy, in which a sample of tissue is taken to be examined under a microscope. The biopsy is usually done during surgery. At the same time, samples of fluid in the abdomen may also be taken and examined.

Many masses found on the ovaries will not be cancer. The diagnosis of ovarian cancer can only be made after tissue or fluid has been sampled and the cells checked by a specialist called a pathologist.

Pelvic examination

In a pelvic examination, the doctor will press gently on the outside of your abdomen (belly) to feel for any masses or lumps. To check your uterus and ovaries, the doctor will place 2 gloved fingers into your vagina while pressing on your abdomen with their other hand.

You may also have a vaginal examination using an instrument called a speculum that gently separates the walls of the vagina.

A pelvic examination should not be painful but it can sometimes be uncomfortable. You can ask for a staff member, family member or friend to be present during the examination.

The doctor may also perform a digital rectal examination, placing a gloved finger into the rectum through the anus. This lets the doctor feel the tissue behind the uterus where cancer cells may grow.

Blood tests

You may have blood tests to check for proteins produced by cancer cells. These proteins are called tumour markers. The most common tumour marker for ovarian cancer is CA125. The level of CA125 may be higher in some cases of ovarian cancer. It can also rise for reasons other than cancer, including ovulation, menstruation, irritable bowel syndrome, some infections such as pneumonia or appendicitis, liver or kidney disease, endometriosis or fibroids.

The CA125 blood test is not used to screen for ovarian cancer if you do not have any symptoms. It can be used:

At diagnosis – A CA125 test is more accurate in diagnosing ovarian cancer if you have been through menopause. If you have early-stage ovarian cancer, CA125 levels are often normal. This is why doctors will often combine CA125 tests with an ultrasound.

During treatment – For ovarian cancer that produces CA125, the blood test may be one way to check how well treatment is working. Falling CA125 levels may mean the treatment is working, and rising CA125 levels may mean the treatment is not working well.

After treatment – CA125 blood tests are sometimes included in follow-up tests.

There is currently no effective screening test for ovarian cancer. The cervical screening test (which replaced the Pap test in 2017) looks for human papillomavirus (HPV). This virus causes

most cases of cervical cancer but it does not cause ovarian cancer. Neither the cervical screening test nor the Pap test can help find ovarian cancer.

Imaging scans

Your doctor may recommend you have some imaging scans to look for a pelvic mass or lump, and to see how big it is. You will need further tests to diagnose any mass as cancer.

Pelvic ultrasound

A pelvic ultrasound uses soundwaves to create a picture of your uterus and ovaries. The soundwaves echo when they meet something dense, such as an organ or tumour. A computer creates a picture from the echoes. A technician called a sonographer does the scan. A pelvic

ultrasound appointment usually takes 15–30 minutes.

A pelvic ultrasound can be done in 2 ways:

Abdominal ultrasound – To get clear pictures of the uterus and ovaries, the bladder needs to be full, so you will be asked to drink water before the appointment. You will lie on an examination table while the sonographer moves a small handheld device called a transducer over your abdomen.

Transvaginal ultrasound – The sonographer inserts a small transducer wand into your vagina. The wand will be covered with a disposable plastic cover and gel to make it easier to insert. You

may find a transvaginal ultrasound uncomfortable, but it should not be painful. If you feel embarrassed or concerned about having this procedure, you can ask for a female sonographer or to have someone in the room with you (e.g. your partner, a friend or a relative).

The transvaginal ultrasound is often the preferred method of ultrasound because it provides a clearer picture of both the ovaries and uterus.

CT scan

A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-rays to create a detailed picture of the inside of the body. A CT scan can be used to check your abdomen, chest and pelvic area, look for signs the cancer has spread, and assist in guiding the needle if doing a biopsy.

The CT scanner is a large, doughnut-shaped machine. You will lie on a table that moves in and out of the scanner. CT scans are usually done at a hospital or radiology clinic.

You will be asked to fast (not eat or drink) before the scan. You may need to have an injection of a special dye, called contrast, which makes your organs appear white in the pictures so anything unusual can be seen more clearly.

A CT scan is noisy but painless. The contrast will be injected into a vein. It may make you feel hot all over, have a sudden urge to pass urine, and leave a bitter taste in your mouth. These sensations usually pass quickly, but tell the person carrying out the scan if they don’t.

The scan takes about 10–20 minutes, but it may take extra time to prepare. You usually go home as soon as the CT scan is over.

MRI scan

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to build up detailed pictures of the inside of your body. While not used often to diagnose ovarian cancer, an MRI may help if it is difficult to tell from the ultrasound whether an ovarian tumour is likely to be cancerous. A contrast may also be used with an MRI.

If you have a pacemaker, let the medical team know before having an MRI. The magnet can interfere with some pacemakers.

During the scan, you will lie on a bench inside a large metal tube that is open at both ends. The noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you may become distressed, mention it beforehand to your medical team. The MRI scan may take between 30 and 90 minutes.

PET–CT scan

A PET (positron emission tomography) scan combined with a CT scan is a specialised imaging test. It provides more information about the cancer than a CT scan on its own.

Only some people will have a PET–CT scan. Medicare covers the cost only for ovarian cancer that has returned, so these scans are not often used to look for ovarian cancer in the first instance. If you are having chemotherapy before surgery, you may have this scan beforehand.

To prepare for a PET–CT scan, you will be asked to fast (not eat or drink) for a period of time. Before the scan, you will be injected with a glucose solution containing a small amount of radioactive material. Cancer cells show up brighter on the scan because they take up more glucose than normal cells do.

You will be asked to sit for 30–90 minutes as the glucose spreads through your body, then you will have the scan. The scan itself will take about 30 minutes. Any radiation will leave your body within a few hours.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to contrast during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Taking a biopsy

The only way to confirm a diagnosis of ovarian cancer is to remove a sample of tissue from the tumour, or to drain fluid from the abdomen or chest if fluid is present. This is sent to a specialist called a pathologist who checks it under a microscope for cancer cells.

Depending on the characteristics of the cancer, your treatment team will recommend the best way to collect the sample, such as:

- surgical biopsy – samples are taken during surgery to remove the mass

- image-guided biopsy – involves removing tissue using a fine needle. The doctor will use a CT scan to guide the needle through skin which has been numbed by a local anaesthetic, into the mass

- fluid sample – fluid, called ascites, is collected in a similar way as an image-guided biopsy, using a fine needle that is guided through the skin during a CT scan. This is a cytology test.

Molecular tests on the sample

If ovarian cancer is found, the biopsy sample or the tissue removed during surgery will usually have more tests. Called molecular tests, these look for gene changes (mutations) and other features in the cancer cells that may help predict the cancer’s response to targeted therapy.

These gene changes are similar to those passed through families, however, for some people with ovarian cancer, the fault is only in the cancer cells. Molecular testing is recommended in most cases if you have high-grade ovarian cancer.

These tests may include HRD testing. HRD stands for homologous recombination deficiency, which is a characteristic of some cancer cells that makes it harder for them to fix or repair damaged DNA.

Testing your samples for HRD can help work out if targeted therapy can be part of your treatment. Medicare subsidies are available for some testing. Your doctor or family cancer clinic will be able to provide more information.

Your treatment team will use the results of molecular testing to help them work out what treatment may work best for you, and what treatment may not be as effective.

Staging ovarian cancer

Once ovarian cancer is diagnosed, it will be staged. This process helps your health care team recommend the best treatment for you.

The staging system most commonly used for ovarian cancer is the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system. Stages 1–2 are early ovarian cancer, while 3–4 are advanced. About 7 out of 10 cases of epithelial ovarian cancer are diagnosed at stage 3 or 4.

Stages of ovarian cancer

The 4 stages of ovarian cancer in the FIGO system may be divided into sub-stages, such as A, B, C, which indicate increasing amounts of tumour.

Stage 1 - Cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes only.

Stage 2 - Cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and has spread to other organs in the pelvis (uterus, bladder or bowel).

Stage 3 - Cancer is in one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes and has spread outside the pelvis to the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum) or nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 4 - The cancer has spread outside the abdomen to distant organs

Grading ovarian cancer

Some types of ovarian cancer will be given a grade. This is a score that describes how the cancer cells look compared with normal cells under a microscope. The grade suggests how quickly the cancer may grow. 24 Understanding Ovarian Cancer Epithelial ovarian cancer is simply divided into low grade and high grade and a number is not given. The most common type of epithelial ovarian cancer is high-grade serous cancer. Sometimes, numbers between 1 and 3 are assigned to other types of ovarian cancers

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

For your prognosis, your doctor will consider test results; the ovarian cancer type, its stage and grade; genetic factors; likelihood of response to treatment; and factors such as your age, fitness and overall health.

Epithelial cancer – If epithelial ovarian cancer is diagnosed and treated when the cancer is only in the ovary (stage 1), it has a good prognosis. Many cases of more advanced cancer may respond well to the initial treatment, but the cancer can often come back (recur) and further treatment is needed.

Stromal cell and germ cell tumours – These can usually be treated successfully, although there may be a small risk that the cancer will come back and need further treatment.

Borderline tumour – This can often be treated successfully with surgery alone.

Discussing your prognosis can be challenging and stressful. It may help to talk with family and friends. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Treatment for ovarian cancer

The treatment for ovarian cancer depends on the type of ovarian cancer you have, the stage of the cancer, whether you wish to have children, whether you have a gene fault, your general health and fitness, and your doctors’ recommendations.

Ovarian cancer is most often treated with surgery and chemotherapy, either on their own, or in combination. Whether you have surgery or chemotherapy first will depend on several factors. Targeted therapy drugs may be offered if there are certain gene changes in the tumour and/or if you have advanced cancer that could not be completely removed with surgery.

Treatment options by type of ovarian cancer

|

epithelial – stage 1 |

usually treated with surgery alone; may be offered chemotherapy after surgery if there is a high risk of the cancer coming back |

|

epithelial – stages 2, 3 and 4 |

usually treated with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy; new targeted therapy drugs are being offered to people with a fault in BRCA or related genes; rarely, radiation therapy is offered |

|

stromal cell |

usually treated with surgery, sometimes followed by chemotherapy or targeted therapy |

|

germ cell |

usually treated with surgery or chemotherapy or both |

|

borderline tumour |

usually treated with surgery only |

Surgery

Surgery is often the initial treatment for ovarian cancer. This surgery can be complex. It is recommended that a gynaecological oncologist who is at a hospital that does a lot of these operations (a high-volume centre) does the surgery. The Australian Society of Gynaecologic Oncologists has a list of specialists by state and territory.

Surgery allows your gynaecological oncologist to confirm the diagnosis of ovarian cancer and also work out if the cancer has spread.

The gynaecological oncologist will talk to you about the most suitable type of surgery, as well as the risks and side effects. These may include infertility. If the option to have children is important to you, talk to your doctor before surgery and ask for a referral to a fertility specialist.

How the surgery is done

You will be given a general anaesthetic and will have either a laparoscopy (with 3–4 small cuts in your abdomen) or a laparotomy (with a vertical cut from around your bellybutton to your pubic line). A laparoscopy may be used to see if a suspicious mass is cancerous; if the cancer is advanced, you will usually have a laparotomy.

Having a surgical biopsy

You may have a biopsy during surgery if you cannot have an image-guided biopsy, or to remove and check a suspicious tumour. The tissue samples will be sent to a pathologist, who will check them for signs of cancer. The results will help decide if you need debulking surgery.

Debulking

If cancer is found, the surgeon will remove as much visible cancer as possible. This is called debulking or cytoreductive surgery. You may also have chemotherapy before or after surgery.

Debulking usually means removing the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus and cervix. Depending on how far the cancer has spread, other organs or tissue may also be removed during the same operation.

Omentectomy – The omentum is a sheet of fatty tissue that hangs down in front of the large bowel like an apron. If the cancer has spread to the omentum, it will need to be removed. The omentum may also be removed even if there is no visible sign cancer has spread, because it may contain cancer cells that cannot be seen during surgery.

Lymphadenectomy – Cancer cells can spread from your ovaries to nearby lymph nodes. Your doctor may suggest removing some nodes in a lymphadenectomy (also called lymph node dissection).

Colectomy – If cancer has spread to the bowel, some of the bowel may need to be removed. Rarely, a new opening called a stoma might be created (colostomy or ileostomy).

Removal of other organs – Ovarian cancer can spread to many organs in the abdomen. In some cases, parts of the liver, diaphragm, bladder and spleen may be removed if it is safe to do so.

"I felt great relief after the surgery, as once the tumour had been removed, the pain that I had in my lower abdomen and hip was gone.” ANN

Types of surgery

If ovarian cancer is found, all or some of the reproductive organs will be removed. The type of surgery you have will depend on how certain the gynaecological oncologist is that cancer is present and where the cancer has spread.

Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

In most cases, surgery for ovarian cancer means removing the uterus and cervix, along with both fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Removing the uterus will mean you cannot get pregnant and carry a child.

Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

If cancer is found early and it is in one ovary, you may have only one ovary and fallopian tube removed.

This may be offered to some younger women with early-stage cancer who still wish to have children.

What to expect after surgery

When you wake up after the operation, you will be in a recovery room near the operating theatre or in the intensive care unit. Once you are fully conscious, you will be taken back to your bed on the hospital ward. The surgeon will visit you as soon as possible to explain the results of the operation.

Tubes and drips – You are likely to have several tubes in place, which will be removed as you recover. These could include:

- a drip inserted into a vein in your arm (intravenous drip) which will give you fluid, medicines and pain relief

- a small plastic tube (catheter) inserted into your bladder to collect urine in a bag

- a tube inserted down your nose into your stomach (nasogastric tube) to drain stomach fluid and prevent vomiting

- tubes inserted into your abdomen to drain fluid from the site of the operation.

Pain – As with all major surgery, you will have some discomfort or pain, but this can be controlled. For the first 1–2 days, you may be given pain medicine through a:

- drip into a vein (intravenous drip)

- local anaesthetic injection into the abdominal wall (a transverse abdominis plane or TAP block) or into the spine (an epidural)

- patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system – you press a button to give yourself a measured dose of pain relief.

Let your doctor or nurse know if you are in pain so they can adjust your medicines to make you as comfortable as possible. Pain that is treated early is better managed. After you go home, you can continue taking pain medicines as needed.

Blood clot prevention – You will be encouraged to move around and be active as soon as you can. It is common to be given a daily injection of blood-thinning medicine to reduce the risk of blood clots. Depending on your risk of clotting, you may be taught to give this injection to

yourself so you can continue it for a few weeks at home. You may also be advised to wear compression stockings for 3–4 weeks to help the blood in your legs to circulate and to avoid clots.

Wound care – You can expect some light vaginal bleeding after the surgery, which should stop within 2 weeks. Your treatment team will talk to you about how you can keep the wound clean to prevent infection once you go home.

If you had part of the bowel removed and have a stoma, a stomal therapy nurse will explain how to manage it.

Length of stay – Your stay in hospital will generally be 1–4 days. How long you stay will depend on the type of surgery you had and how quickly you recover. If you had laparoscopic surgery, you will be able to go home on the first or second day after the operation.

Taking care of yourself at home after surgery

Your recovery time will depend on the type of surgery you had, your general health, and your support at home. If you don’t have support from family, friends or neighbours, ask your nurse or the hospital social worker if it’s possible to get help at home. In most cases, you will feel better within 1–2 weeks and should be able to fully return to your usual activities after 4–8 weeks. Ask your treatment team for more information about your particular circumstances.

Rest up – When you get home from hospital, take things easy and do only what is comfortable. You may like to try meditation or some relaxation techniques to reduce anxiety or tension.

Lifting – Avoid heavy lifting (more than 3–4 kg) or heavy work (e.g. gardening) for at least 6–8 weeks. This will depend on the method and kind of surgery you’ve had.

Work – Depending on the type of work you do, you will probably need time off work. Ask your treatment team how long this might be.

Driving – You will need to avoid driving after the surgery until pain in no way limits your ability to move freely. Discuss this issue with your doctor. Check with your car insurer for any exclusions regarding major surgery and driving.

Exercise – Your treatment team will probably encourage you to walk on the day of the surgery. Research suggests that exercise helps manage some treatment side effects and speed up a return to usual activities. Speak to your doctor about suitable exercise and ask for a referral to a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist. To avoid infection, it’s best to avoid swimming for 5–6 weeks after surgery.

Bowel problems – You may experience constipation after having a hysterectomy and taking

strong pain medicines. You will probably be offered stool softeners while you’re taking pain

medicines and until your bowel movements return to normal.

Eat well – To help your body recover from surgery, eat a well-balanced diet that includes a variety of foods. Include proteins such as lean meat, fish, eggs, milk, yoghurt, nuts and legumes/beans.

Sex – Sexual intercourse should be avoided for up to 8 weeks after a hysterectomy. Ask your

doctor or nurse when you can have sex again, and explore ways you and your partner can be intimate.

Will I need further treatment after surgery?

All tissue and fluids removed during surgery are checked for cancer cells by a pathologist. The results will help confirm the type of ovarian cancer you have, if it has spread (metastasised), and its stage.

Your doctor should have all the test results within 2 weeks of surgery. Further treatment will depend on the type, stage and grade of the cancer.

If the cancer is advanced, it’s more likely to come back, so surgery will usually be followed by chemotherapy, and occasionally by targeted therapy. Radiation therapy is recommended only in particular cases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the treatment of cancer with anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to normal, healthy cells.

When you have chemotherapy depends on the stage of the cancer. It may be used at different times:

Before surgery – For stage 3 or 4 ovarian cancer, chemotherapy is sometimes given before surgery. This is known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The aim is to shrink the tumours to make them easier to remove.

After 3–4 cycles of chemotherapy, you will have a CT scan to check how the tumour has responded to the chemotherapy. Your doctor or multidisciplinary team will then decide whether to recommend an operation. If you have surgery, you will have another 2–3 cycles of chemotherapy afterwards. If you do not have surgery, you will continue with a further 3 cycles of chemotherapy.

After surgery – Chemotherapy is usually given 2–4 weeks after the surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) as there may be some cancer cells still in the body. For ovarian cancer, the drugs are usually given in repeating cycles spread over 4–5 months, but this can vary depending on the stage of the cancer and your general health. Your treatment team will talk to you about your specific schedule. Some people may have chemotherapy and a targeted therapy drug.

Main treatment – Chemotherapy may be recommended as the main treatment if you are not well enough for a major operation or when the cancer cannot be surgically removed.

Having chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is usually given as a combination of 2 or more drugs, or sometimes as a single drug.

In most cases, the drugs are injected into a vein (intravenously). To reduce the need for repeated needles, you may receive chemotherapy through a small medical appliance or tube inserted beneath your skin. This may be called a port-a-cath or a peripherally inserted central

catheter (PICC), or it may have another name.

You will usually have chemotherapy as an outpatient (also called a day patient), but some people need to stay in hospital overnight.

Chemotherapy is commonly given as a period of treatment followed by a break. This is called a cycle. The break between the cycles lets your normal cells recover and your body regain its strength.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Occasionally, chemotherapy is given directly into the abdominal cavity (the space between organs in the abdomen and the walls of the abdomen). This is known as intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

In this method, the drugs are delivered through a tube (catheter) that is put in place during surgery and removed once the course of chemotherapy is over.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is used only in specialised units in Australia. It may be offered for stage 3 cancer with less than 1 cm of tumour remaining after surgery. Some studies have shown it may be more effective than giving chemotherapy through an intravenous drip.

There are other studies looking at giving heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) at the time of surgery.

Ask your medical oncologist for more information about this type of chemotherapy, its benefits and risks, and if it is suitable for you.

Blood tests during chemotherapy

You will have blood tests before each chemotherapy cycle, to check that your body’s healthy cells have had time to recover. If your blood count has not recovered, which can be common, there may be a delay before your next treatment.

If you had raised CA125 levels when you were diagnosed, you may also have blood tests during treatment to check what is happening to these levels. The blood tests will check if:

- CA125 levels fall during treatment – this can mean the chemotherapy is destroying the cancer cells

- CA125 levels stay the same or rise during treatment – this may mean the cancer is not responding to chemotherapy.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Chemotherapy’

Side effects of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can affect healthy cells in the body, which may cause side effects. Not everyone will have side effects, and they will vary according to the drugs you are given. Your treatment team will talk to you about what to expect and how to manage any side effects.

Fatigue – This is very common during and after cancer treatment, but can also be caused by other factors. Your red blood cell level may drop (anaemia), which can cause you to feel tired and short of breath.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Fatigue and Cancer’

Nausea and vomiting – Some types of chemotherapy drugs may make you feel sick (nauseous) or vomit. You will probably be given anti-nausea medicines with each chemotherapy session to help prevent or reduce nausea and vomiting. Whether or not you feel sick is not a sign of how well the treatment is working.

Changed bowel habits – Some chemotherapy drugs, pain medicines and anti-nausea drugs can cause constipation or diarrhoea. Ensure you tell your doctor or nurse if your bowel habits have changed.

Joint and muscle pain – This may occur after your treatment session. It may feel like you have the flu, but the symptoms should disappear within a few days. Ask your doctor if taking a mild pain medicine such as paracetamol may help.

Risk of infections – Chemotherapy reduces your white blood cell level, making it harder for your body to fight infections. Colds, flu and viruses may be easier to catch and harder to shake off, and scratches or cuts may get infected more easily. You may also be more likely to catch a serious infection and need to be admitted to hospital. Contact your doctor or go to the nearest hospital immediately if you have one or more symptoms of an infection, such as:

- temperature of 38°C or above

- chills or shivering

- burning or stinging feeling when urinating

- a severe cough or sore throat

- severe abdominal pain, constipation or diarrhoea

- any sudden decline in your health.

Hair loss – Depending on the chemotherapy drug you receive, you will probably lose your head and body hair. Some treatment centres offer cold caps for your head, which may reduce the amount of hair loss.

The hair will grow back after treatment ends, but the colour and texture may be different for a while. If you choose to wear a wig until your hair grows back, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to find out about wig services in your area. If you have private health insurance, check whether they’ll cover the cost of a wig because of hair loss related to chemotherapy.

Download our fact sheet ‘Hair Loss’

Numbness or tingling in your hands and feet – This is known as peripheral neuropathy, and it can be a side effect of certain chemotherapy drugs. Let your doctor know if this happens, as your dose of chemotherapy may need to be adjusted.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Peripheral Neuropathy and Cancer’

"I kept a notebook to record my chemotherapy symptoms and any questions I had to ask my oncologist at each appointment.” ANN

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy drugs can target specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. These drugs are used to treat advanced ovarian cancer or ovarian cancer that has come back (recurred). Whether you are offered targeted therapy drugs will depend on the following:

- the type of ovarian cancer you have

- other treatments you’ve already had and if they’ve worked

- whether you have a particular gene change that may respond to targeted therapy drugs.

Types of targeted therapy drugs

Olaparib and niraparib – These targeted therapy drugs are used to treat people with high-grade epithelial cancer who have changes in the BRCA genes or other genes related to ovarian cancer. You may be offered olaparib or niraparib after initial chemotherapy. This is known as maintenance treatment. Or you may have olaparib or niraparib if the cancer has come back (recurred). Olaparib is taken as a tablet twice a day and niraparib is taken as a tablet once a day for as long as they appear to be helping control the cancer.

Bevacizumab – This targeted therapy drug is sometimes used to treat advanced epithelial tumours. It is given with chemotherapy every 3 weeks as a drip into a vein (intravenous infusion). Treatment will continue for about 12 months if used as part of the initial treatment, or for as long as it’s working if it is used for cancer that has come back.

Other targeted therapy drugs may be available in clinical trials. Talk with your doctor about what new drugs are available and whether you are a suitable candidate.

Side effects of targeted therapy

Although targeted therapy drugs limit damage to healthy cells, they can still have side effects. These vary for each person depending on the drug you are given and how your body responds.

It is important to tell your doctor about any new or worsening side effects. If left untreated, some can become life-threatening. Your doctor will monitor you throughout your treatment.

The most common side effects of olaparib and niraparib include nausea, fatigue, diarrhoea and low blood cell counts. More serious side effects include bone marrow problems.

The most common side effects of bevacizumab include bleeding, skin rash, high blood pressure and kidney problems. In very rare cases, small tears (perforations) may develop in the bowel or stomach wall.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of drug treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

In Australia, immunotherapy drugs are currently available as treatment options for some types of cancer, such as melanoma and lung cancer.

At present, immunotherapy has not been proven to help treat ovarian cancer. International

clinical trials are continuing to test immunotherapy drugs for treating ovarian cancer.

You can ask your treatment team for the latest updates.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. The radiation is usually delivered in the form of x-ray beams.

Radiation therapy is occasionally used to treat ovarian cancer that has spread to the pelvis or to other parts of the body. It may be used after chemotherapy or surgery to help reduce the symptoms of advanced cancer, or on its own as a palliative treatment.

For each radiation therapy session, you will lie on a treatment table under a large machine that delivers radiation to the affected parts of the body. You will not feel anything during the treatment, which will take only a few minutes each time. You may be in the room for a total of 10–20 minutes for each appointment.

How many radiation therapy sessions you have will depend on several factors, including the type and size of the cancer and where it is located. You may have a few treatments, or daily treatments for several weeks.

Side effects of radiation therapy

The side effects of radiation therapy vary. Most are temporary and disappear a few weeks or months after treatment. Radiation therapy for ovarian cancer is usually given over the lower abdominal/pelvic area, which can irritate the bowel and bladder. It can also cause infertility.

Common side effects include feeling tired, diarrhoea, needing to pass urine more often, a burning feeling when passing urine (cystitis), and, less often, a slight reddening of the skin around the treatment site.

More rarely, you may have some nausea or vomiting. If this occurs, you will be prescribed medicine to control it.

Radiation therapy can also have long-term side effects that may occur months or years after therapy. These can include scarring of the bladder, vagina and bowel, as well as a very small increase in the risk of cancers in the decades after therapy.

Palliative treatment

Palliative treatment helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease. It is best thought of as supportive care.

Many people think that palliative treatment is only for people at the end of their life, but it can help people at any stage of advanced ovarian cancer, even if they are still having active treatment for the cancer. It is about living for as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

Palliative treatment can slow the spread of cancer, relieve pain and help manage other symptoms. Treatment may include palliative forms of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. If fluid builds up and causes uncomfortable swelling or breathlessness, you may have a procedure to drain the extra fluid from your abdomen or lungs.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Managing side effects

Treatment can cause physical and emotional changes.

Some people experience many side effects, while others have few. Most side effects are temporary, but some may be permanent. It is important to tell your treatment team about any new or ongoing side effects you have, as they will often be able to help you manage them.

This section offers tips for coping with some common side effects.

Fatigue

It is common to feel very tired and lack energy during or after treatment. Fatigue for people with cancer is different from tiredness as it doesn’t always go away with rest or sleep. Most people who have chemotherapy will start treatment before they have had time to fully recover from their operation. Fatigue may continue for a while after chemotherapy has finished, but it is likely to gradually improve over time. In some cases, it may take 1–2 years to feel well again.

Tips for managing fatigue

- Plan your day. Set small, manageable goals and rest before you get too tired.

- Ask for and accept offers of help with tasks such as cleaning and shopping.

- Eat healthy, well-balanced meals to keep energy levels up.

- Do some light exercise. This has been shown to boost energy levels and make you feel less tired.

- Talk to your doctor about what type of exercise would be suitable for you.

Infertility

Having surgery or radiation therapy for ovarian cancer may mean you will be unable to conceive a child. This is known as infertility. If you have stage 1 ovarian cancer and have not yet reached menopause, it may be possible to leave the uterus and one ovary in place (unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Talk to your doctor or a fertility specialist about what options are available to you.

Being told that your reproductive organs will be removed or will no longer work and that you won’t be able to have children can be devastating. Even if your family is complete or you do not want children, you may still feel a sense of loss and grief.

Speaking to a counsellor or gynaecological oncology nurse about your feelings can be helpful.

Menopause

If you were still having periods (menstruating) before surgery, having your ovaries removed will mean your periods will stop. This is called menopause. When menopause occurs naturally, it is a gradual process that usually starts between the ages of 45 and 55, but menopause after surgery is sudden.

Symptoms of menopause can include hot flushes, dry or itchy skin, mood swings, trouble sleeping (insomnia), tiredness and vaginal dryness. These symptoms are usually more intense after surgery than during a natural menopause, because the body hasn’t had time to get used to the gradual decrease in hormone levels. If symptoms are causing problems for you, speak to your treatment team or doctor.

Managing the symptoms of menopause

Check your cholesterol levels – Cholesterol levels can change after menopause, which can lead to heart disease. You can manage cholesterol levels with regular exercise and a balanced diet. Ask your doctor about cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Use a vaginal moisturiser – This will help with vaginal discomfort and dryness. You can buy a vaginal moisturiser over the counter from chemists.

Learn meditation and relaxation techniques – These may help reduce stress and lessen symptoms.

Ask about menopause hormone therapy (MHT) – Previously called hormone replacement therapy (HRT), there are benefits and risks to managing menopause with MHT. Ask your oncologist if MHT is safe for you to use after treatment for ovarian cancer.

Have your bone density checked – Menopause can increase your risk of developing thinning of the bones (osteoporosis). Talk to your doctor about having a bone density test or taking medicines to prevent your bones becoming weak. Regular exercise will help keep your bones strong. For more information, visit Healthy Bones Australia or call them on 1800 242 141.

Impact on sexuality and intimacy

How ovarian cancer affects your sexuality depends on many factors, such as treatment and side effects, your self-confidence, and whether you have a partner. It is natural to experience changes in your desire to have sex.

It is important that your sexuality is respected and you feel comfortable when discussing how cancer treatment will affect you. Whatever your gender identity or sexual orientation, your medical team should be able to discuss your needs and support you through treatment.

Physical changes – Treatment can cause dryness and scarring of the vagina, and internal scar tissue. These side effects can make sexual penetration painful, and you may have to find different ways to orgasm. Removal of the uterus, cervix and ovaries can change how you experience sexual pleasure. The experience of having cancer may mean you lose interest in intimacy and sex (low libido).

Emotional changes – For most people, sex is more than arousal, intercourse and orgasms. It involves feelings of intimacy and acceptance, as well as being able to give and receive love. Although sexual intercourse may not always be possible, closeness and sharing can still be part of your relationship.

Changes to your body can affect the way you feel about yourself (your self-esteem) and make you feel self-conscious. You may feel less confident about who you are and what you can do. Give yourself time to get used to any changes. You may benefit from talking to a professional such as a psychologist or sexual therapist. Your doctor will be able to help with a referral.

Tips for managing sexual changes

- Enjoy physical touch with your partner without having sexual intercourse to maintain intimacy.

- Try touching, hugging, massaging, holding hands and having a bath together.

- Let your partner know if you don’t feel like having sex, or if you find penetration uncomfortable.

- Talk to your doctor about ways to manage side effects that change your sex life. These may include using vaginal dilators, lubricants and moisturisers.

- If you find that vaginal dryness is a problem, take more time before and during sex to help the vagina relax and become well aroused.

- Lubricant helps with vaginal dryness. A water-based or silicone-based gel with no added perfumes or colouring is best.

- Try different positions during sex to work out which position is the most comfortable for you.

- Spend more time on foreplay and try different ways to become aroused.

- If you can’t enjoy penetrative sex, explore other ways, such as oral and manual stimulation.

- Talk about how you’re feeling with your sexual partner or doctor, or ask your treatment team for a referral to a sexual therapist or psychologist.

- Do some regular physical activity to boost your energy and mood.

- Talk to your GP about managing any depression as it may be affecting your libido and desire for intimacy.

- For ideas on how to talk to your treatment team about sexual changes, see .

Bowel changes

After surgery or during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, some people notice changes in how their bowel works. You may have diarrhoea, constipation or stomach cramps. Pain medicines may also make you feel constipated. Diarrhoea and constipation can occur for some time, but are usually temporary.

Sometimes tissues in the pelvis stick together after surgery. This is called a pelvic adhesion, and it can be painful and cause ongoing bowel problems such as constipation. In rare cases, it may need further surgery.

To help manage bowel changes, ask your doctor, nurse or dietitian for advice about eating and drinking, and see the tips below.

Tips for managing bowel changes

- Drink plenty of liquids to replace fluids lost through diarrhoea or to help soften faeces (poo) if you are constipated. Avoid alcohol, caffeinated drinks and very hot or very cold liquids.

- Avoid fried, spicy or greasy foods, which can cause pain and make diarrhoea and constipation worse.

- If you have diarrhoea, rest as much as possible. Diarrhoea can make you feel very tired.

- Ask your pharmacist or doctor about suitable medicines to relieve symptoms of diarrhoea or constipation.

- Eat small, frequent meals instead of 3 big ones.

- Drink peppermint or chamomile tea to reduce stomach or wind pain.

- If you are constipated, consider taking laxatives and do some gentle exercise, such as walking.

Treating a blockage in the bowel

When food can’t pass through the bowel it can become blocked. This is known as a bowel obstruction. Causes may include surgery or radiation therapy, or the cancer coming back. Symptoms may include feeling sick, vomiting, or a swollen and painful stomach. Bowel obstruction can be serious. How it is treated will depend on its cause, where it is in the bowel, and your general health. Options may include:

Resting the bowel – A bowel obstruction can sometimes be treated by resting the bowel, which means not eating or drinking and having fluid through an intravenous drip until the blockage clears.

Taking medicines – Your doctor may prescribe an anti-inflammatory medicine to reduce the swelling around the obstruction.

Inserting a stent – Surgery may help clear some bowel obstructions. If only one area is blocked, you may have a small tube (stent) put in to help keep the bowel open and relieve symptoms. The stent may be inserted through the rectum using a flexible tube called an endoscope.

Creating a stoma – If the bowel is blocked in more than one spot, you may have a stoma. This is a surgically created opening in the abdomen that allows waste matter to leave the body. A stoma may be a colostomy (made from the colon in the large bowel) or an ileostomy (made from the ileum in the small bowel). A small bag called a stoma bag or appliance is worn on the outside of the body to collect the waste. The stoma may be reversed when the blockage is cleared, or it may be permanent.

For more information on caring for a stoma, visit the Australian Association of Stomal Therapy Nurses or the Australian Council of Stoma Associations.

Fluid build-up

Sometimes ovarian cancer can cause fluid to build up in different parts of the body.

Ascites – This is when fluid collects in the abdomen. It causes swelling and pressure, which can be uncomfortable and make you feel breathless.

If you have ascites, your doctor may inject a local anaesthetic into the abdomen and then insert a needle to take a sample of the fluid. This is called a paracentesis or ascitic tap. The fluid sample is sent to a laboratory to be examined under a microscope for cancer cells.

Sometimes, to make you feel more comfortable, the doctor will remove all the remaining fluid from your abdomen. If there is a lot of fluid, it may take a few hours for the fluid to drain into a drainage bag, and then the tube will be removed from your abdomen.

Pleural effusion – If the cancer has spread to the lungs, fluid builds up in the area between the lung and the chest wall (pleural space). It can cause pain and breathlessness. The fluid can be drained using a procedure called a thoracentesis or pleural tap. Your doctor will inject a local anaesthetic into the chest area, and then insert a needle into the pleural space to drain the fluid.

Lymphoedema

If you have lymph nodes removed from the pelvis as part of surgery (a lymphadenectomy), you may find that one or both legs become swollen. This is known as lymphoedema. It can happen if lymph fluid doesn’t circulate properly and builds up in the legs. Radiation therapy in the pelvic area may also cause lymphoedema.

Lymphoedema can make movement and some types of activities difficult. The swelling may appear at the time of treatment or months or years later. It is important to seek help with lymphoedema symptoms as soon as possible because early diagnosis and treatment lead to better outcomes.

Tips for managing lymphoedema

Manage and reduce the swelling of lymphoedema with gentle exercise, compression stockings and a type of massage called manual lymphatic drainage.

Keep your skin clean and apply moisturiser every day.

Protect your skin from cuts, scratches, bites and burns to reduce the risk of infection.

- See a trained lymphoedema practitioner for a treatment plan and ongoing care. Visit the Australasian Lymphology Association website for more information.

- Visit the SA Health website for information on the Lymphoedema Compression Garments Subsidy Scheme.

- Talk to your GP about how a Chronic Disease Management Plan can help you manage the condition.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had ovarian cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After your treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. These are known as follow-up appointments and are times for you to discuss any concerns you may have.

In most cases, follow-up appointments will be with your gynaecological oncologist and sometimes the medical oncologist. They will usually perform a physical examination, which may include an internal examination, and arrange blood tests before each visit.

Scans such as CT or PET–CT may be arranged if you develop symptoms, your blood test detects a rise in the tumour marker or your doctor wants more information.

There is no set follow-up schedule for ovarian cancer, but it’s common to see a specialist every 3 months for the first few years, and then every 4–6 months for up to 5 years. Some people prefer not to follow a schedule but to see their specialist if they experience symptoms. Talk with your doctor about the right follow-up plan for you.

Your check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems, and the cancer has not come back. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

Having CA125 blood tests

Your specialist will also talk to you about the advantages and disadvantages of having regular blood tests for the tumour marker CA125. This test is optional.

There is research to suggest that waiting until new symptoms develop before starting treatment is just as effective as starting treatment earlier because of a rise in CA125. Not having treatment until you have new symptoms may mean that your quality of life is better for longer because side effects of further treatment are delayed.

For germ cell or stromal tumours, you may have blood tests for tumour markers other than CA125.

What if ovarian cancer returns?

If ovarian cancer is advanced at diagnosis, it often does come back after treatment and a period of improvement (remission). This is known as a recurrence and it is why regular follow-up appointments are important. In some cases, there may be a number of recurrences, with long gaps in between when cancer treatment is not needed. Early-stage ovarian cancer is less likely to come back than advanced ovarian cancer.

The most common treatment for epithelial ovarian cancer that has come back is more chemotherapy or targeted therapy. The drugs used will depend on what drugs you had initially, the length of remission, and the aim of the treatment, as well as your general health and any side effects from previous treatments. The drugs used the first time may be given again if you have a good response to them and the cancer stays away for 6 months or more.

New drugs are constantly being developed and tested. Genetic tests and targeted therapy are offering new treatment options for people with ovarian cancer. Talk with your doctor about the latest developments in the treatment of ovarian cancer, and whether a clinical trial may be right for you.

Living with ovarian cancer

One of the challenges of a cancer diagnosis is dealing with uncertainty. When first diagnosed, many people want to know what’s going to happen and when it will be over. But living with uncertainty is part of having cancer, especially if the cancer is advanced.

There will be some questions that will have no answers. Learning as much as you can about the cancer and its treatment may make you feel more in control.

Tips for living with ovarian cancer

- Talk with other people who have had ovarian cancer. You may find it reassuring to hear about their experiences.

- Explore different ways to relax, such as meditation or yoga.

- Talk to a psychologist or counsellor about how you are feeling – they may be able to teach you some strategies to help you manage your fears.

- Keep a diary to track how you’re feeling.

- Set yourself some achievable goals.

- Practise letting your thoughts come and go without getting caught up in them.

- Try to exercise regularly. Research shows that exercise can help people cope with the side effects of treatment.

- Focus on making healthy choices in areas of your life that you can control, such as eating well and getting regular exercise.

Listen to our podcast episode ‘Living Well with Advanced Cancer’

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication, even for a short time, may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA offers a free counselling service, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on

1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.