The pancreas

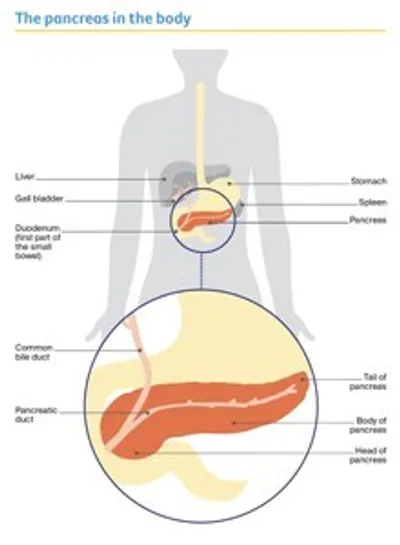

The pancreas is a long, flat gland that lies between your stomach and spine.

It is about 13–15 cm long and is divided into 3 main parts:

- the large, rounded end, called the head of the pancreas

- the middle part, known as the body

- the narrow end, called the tail, that sits up next to your spleen.

A tube called the pancreatic duct connects the pancreas to the first part of the small bowel (duodenum). Another tube, called the common bile duct, runs through the head and joins with the pancreatic duct to connect the liver and gall bladder to the duodenum.

What the pancreas does

The pancreas has 2 main jobs. It makes digestive juices (known as its exocrine function) and hormones (its endocrine function).

Exocrine function – The pancreas is part of the digestive system, which helps the body digest food and turn it into energy. Exocrine cells make pancreatic enzymes, which are digestive juices. The pancreatic duct carries these juices from the pancreas into the duodenum, where they help to break down food. Most of the pancreas is made up of exocrine tissue.

Endocrine function – The pancreas is also part of the endocrine system. This is a group of glands that makes the body’s hormones. Endocrine cells in the pancreas make hormones that control blood sugar levels, the amount of acid produced by the stomach, and how quickly food is absorbed. For example, the hormone insulin decreases the level of sugar in the blood, while the hormone glucagon increases it.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about pancreatic cancer are below.

What is pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is cancer that starts in any part of the pancreas. About 3 in 4 pancreatic cancers are found in the head of the pancreas.

Pancreatic cancer can spread to nearby lymph nodes and to the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum). Cancer cells may also travel through the bloodstream to other parts of the body, such as the liver.

What are the main types?

There are 2 main groups of pancreatic cancer:

Exocrine tumours – These make up more than 95% of pancreatic cancers. The most common type is called adenocarcinoma, and it starts in the exocrine cells lining the pancreatic duct. Less common types include adenosquamous carcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma.

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) – About 5% of cancers in the pancreas are pancreatic NETs. These start in the endocrine cells.

This information is about exocrine tumours of the pancreas, particularly pancreatic adenocarcinomas.

For more information about how pancreatic NETs are diagnosed and treated, see our Understanding Neuroendocrine Tumours fact sheet.

What are the symptoms?

Early-stage pancreatic cancer rarely causes obvious symptoms. Symptoms may not appear until the cancer is large enough to affect nearby organs or has spread.

The first symptom of pancreatic cancer is often jaundice. Signs of jaundice may include yellowish skin and eyes, dark urine, pale bowel motions and itchy skin. Jaundice is caused by the build-up of bilirubin, a dark yellow-brown substance found in bile. Bilirubin can build up if pancreatic cancer blocks the common bile duct. Other common symptoms of pancreatic cancer include:

- appetite loss

- nausea (with or without vomiting)

- unexplained weight loss

- pain in the upper abdomen, side or back, which may cause you to wake up at night

- changed bowel motions – including diarrhoea, severe constipation, or pale, oily, foul-smelling stools (poo) that are difficult to flush away in the toilet

- bloating and passing wind and burping more than usual

- newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes

- fatigue (feeling very tired).

"I went to the doctor because I was itchy and had constant diarrhoea. My GP initially thought it was gallstones and sent me for routine tests. After the CT scan I went into hospital for a laparoscopy and then had a biopsy, which confirmed I had cancer.” JAN

These symptoms can also occur in many other conditions and do not necessarily mean that you have cancer. If you are worried or have ongoing symptoms, speak with your general practitioner (GP).

What are the risk factors?

The causes of pancreatic cancer are not known, but research has shown that people with certain risk factors are more likely to develop pancreatic cancer. Factors that are known to increase the risk of getting pancreatic cancer include:

- smoking tobacco (smokers are about twice as likely to develop pancreatic cancer as nonsmokers)

- obesity

- ageing

- long-term diabetes (but diabetes can also be caused by the pancreatic cancer)

- long-term pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- certain types of cysts in the pancreatic duct known as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) – these should be assessed by an appropriate specialist

- stomach infections caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacteria (which can also cause stomach ulcers)

- family history and inherited conditions

- workplace exposure to certain pesticides, dyes or chemicals.

Having risk factors does not mean you will definitely get cancer, but talk to your doctor if you are concerned. Some people with pancreatic cancer have no known risk factors.

How common is pancreatic cancer?

About 4500 people are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in Australia each year. More than 80% of those diagnosed are over the age of 60.

Pancreatic cancer was estimated to be the 8th most common cancer in Australia in 2023 and it affects men and women at about the same rate.

What can I expect after diagnosis?

It’s common to have many questions and concerns about what a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer will mean for you. These pages have sections that explain the process of diagnosis, treatment options for removing the cancer and managing symptoms, and coping with physical changes that affect what you can eat.

If you are feeling overwhelmed or would just like to talk through your concerns, you can call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to speak to one of our experienced health professionals.

Where should I have treatment?

Treatment for pancreatic cancer is highly specialised. This is particularly the case for the surgery for early pancreatic cancer, such as the Whipple procedure.

There is strong evidence that outcomes are better when people have their treatment in a specialist centre that sees a lot of people with pancreatic cancer. These high-volume centres have multidisciplinary teams of health professionals experienced in treating pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer centres offer access to a wide range of treatment options – including treatments available only through clinical trials – but it may mean you need to travel away from home for treatment.

Sometimes the multidisciplinary team from a specialist centre will be able to advise your local specialist. You may find that you can visit the specialist centre to confirm the diagnosis and work out a treatment plan to have much of your treatment closer to your home.

To find a treatment centre that specialises in pancreatic cancer, talk to your GP.

If you live in a rural or regional area and have to travel a long way for appointments or treatment, you may be able to get financial assistance towards the cost of accommodation or travel. To check whether you are eligible or to apply for this assistance, speak to your GP or the hospital social worker, or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your GP will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist or surgeon. The specialist will arrange further tests. If pancreatic cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Health professionals you may see

- Pancreatic or HPB (hepato-pancreatobiliary) surgeon – operates on the liver, bile ducts, pancreas and surrounding organs

- Gastroenterologist – diagnoses and treats disorders of the digestive system; may diagnose pancreatic cancer, perform endoscopy, and insert stents to clear blocked bile ducts

- Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy (systemic treatment)

- Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

- Endocrinologist – diagnoses and treats hormonal disorders, including diabetes

- Radiologist – analyses x-rays and scans; an interventional radiologist may also perform a biopsy under ultrasound or CT, and deliver some treatments

- Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

- Nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

- Palliative care team – a team of specialist doctors, nurses and allied health workers who work closely with the GP and oncologist to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life

- Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

- Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

- Psychologist, counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

- Physiotherapist, exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve

fitness and wellbeing - Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

How is pancreatic cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor thinks you may have pancreatic cancer, you will need some tests to confirm the diagnosis.

These may include blood tests, CT, MRI and other imaging scans, endoscopic tests and tissue sampling (called a biopsy). You may also have tests to check for gene changes in the cancer. The tests you have will depend on the symptoms, type and stage of the cancer.

You will not have all the tests described below.

Blood tests

You are likely to have blood tests to check your general health and see how well your liver and kidneys are working. Some blood tests look for proteins produced by cancer cells. These proteins are known as tumour markers.

Tumour markers

Many people with pancreatic cancer have higher levels of particular tumour markers in their bloodstream. The markers that doctors will look for are CA 19-9 (carbohydrate antigen) and CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen). On their own, however, these tumour markers can’t be used to diagnose pancreatic cancer. This is because some people with pancreatic cancer have normal levels of these markers, and other conditions can also raise the levels of these markers in the bloodstream.

It is normal for the levels of these tumour markers to go up and down a little. Your doctor will look for sharp increases and overall patterns. Raised levels can tell your doctor more about the cancer and, after diagnosis, can also show how well the treatment is working.

Imaging scans

Imaging scans are tests that create pictures of the inside of the body. Different scans can provide different details about the cancer.

You will usually have at least one of the following scans during diagnosis and treatment.

CT scan

Most people suspected of having pancreatic cancer will have a CT (computerised tomography) scan. This scan uses x-ray beams to take many pictures of the inside of your body and then compiles them into one detailed, cross-sectional picture.

A CT scan is usually done at a hospital or a radiology clinic. Before the scan, a liquid dye (called contrast) will be injected into a vein to help make the pictures clearer. The dye travels through your bloodstream to the pancreas and nearby organs and helps show up any abnormal areas. This may cause you to feel hot all over, may give you a strange taste in your mouth and you could feel as if you need to pass urine (pee). These reactions are temporary and usually go away in a few minutes, but tell your treatment team if you feel unwell.

The CT scanner is large and round like a doughnut. You will need to lie still on an examination table while the scanner moves around you. The scan itself is painless and takes only a few minutes, but getting it set up can take 10–30 minutes.

Endoscopic tests

Endoscopic tests can show blockages or inflammation in the common bile duct, stomach and duodenum. For these tests, you will have an endoscopy, a procedure that is usually done as day surgery by a specialist doctor called a gastroenterologist. The doctor passes a long, flexible tube with a light and small camera on the end (endoscope) down your throat into your digestive tract. There are 2 main types of endoscopic tests:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) – An EUS uses an endoscope with an ultrasound probe (transducer) attached. The endoscope is passed through your mouth into the small bowel. The transducer makes soundwaves that create detailed pictures of the pancreas and ducts. This helps to locate small tumours and shows if the cancer has spread into nearby tissue. A biopsy of the cancer can be taken at the same time.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) – An ERCP is used to take an x-ray of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct. The doctor uses the endoscope to guide a tube into the bile duct and insert a small amount of dye. The x-ray images show blockages or narrowing that might be caused by cancer. ERCP may also be used to put a thin plastic or metal tube (stent) into the bile duct to keep it open.

During an endoscopic procedure, the doctor can also take a tissue or fluid sample (biopsy) to help with the diagnosis.

You will be asked not to eat or drink (fast) for 6 hours before an endoscopic test. The doctor will give you medicine to help you relax and feel as comfortable as possible. Because of this medicine, you shouldn’t drive or operate machinery until the next day.

Having an endoscopic test has some risks, including infection, bleeding and inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis). These complications are not common. Your doctor will explain the risks before asking you to agree (consent) to the procedure.

MRI and MRCP scans

In some cases, you may also have another type of scan such as an MRI or MRCP scan. An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional pictures of the pancreas and nearby organs. An MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) scan is a different type of MRI scan that produces more detailed images and can be used to check the common bile duct for a blockage (obstruction).

An MRI or MRCP takes about an hour and you will be able to go home when it is over. Before the scan, you may be asked not to eat or drink (fast) for a few hours. You may also be given an injection of dye (contrast) to highlight the organs in your body.

During the scan, you will lie on a treatment table that slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends. The noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you might be distressed, mention this beforehand to your doctor or nurse. You may be given medicine to help you relax, and you will usually be offered headphones or earplugs. Also let the doctor or nurse know if you have a pacemaker or any other metallic object in your body, as this can interfere with the scan.

MRIs for pancreatic cancer are not always covered by Medicare. If this test is recommended, check with your treatment team what you may have to pay.

PET–CT scan

Doctors sometimes use a PET (positron emission tomography) scan combined with a CT scan to help work out if the pancreatic cancer has spread or how it is responding to treatment.

It may take several hours to prepare for and complete a PET–CT scan. Before the scan you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive material, usually a glucose solution called fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Some cancer cells will show up brighter on the scan because they take up more of this solution than normal cells do.

PET–CT scans are specialised tests. They are not available in every hospital and may not be covered by Medicare, so talk to your medical team for more information.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Tissue sampling

If imaging scans show there is a tumour in the pancreas, your doctor may remove a sample of cells or tissue from the tumour (biopsy).

This is the main way to confirm if the tumour is cancer and to work out exactly what type of cancer it is. A specialist doctor called a pathologist will examine the sample under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. Sometimes, the results are not clear and a second biopsy is needed.

A biopsy can be taken in different ways, including:

With a needle – A sample of cells may be collected with a fine needle (fine needle biopsy), or a tissue sample may be collected with a larger needle (core biopsy). A fine needle or core biopsy can be done during an endoscopic procedure. Another method is to insert the needle through the skin of the abdomen, using an ultrasound or CT scan for guidance. You will be awake during the procedure, but you will be given a local anaesthetic so you do not feel any pain.

During keyhole surgery – Also called a laparoscopy or minimally invasive surgery, keyhole surgery is sometimes used to look inside the abdomen to see if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. It can also be done to take tissue samples before any further surgery.

Keyhole surgery is done under general anaesthetic, so you will be asked not to eat or drink (fast) for 6 hours beforehand. If you take blood-thinning medicines or have diabetes, let your doctor or nurse know before the surgery as they may need to adjust your medicines in the days leading up to the procedure.

The procedure uses an instrument called a laparoscope (a long tube with a light and camera on the end). The camera projects images onto a screen so the doctor can see inside your body. The doctor will guide the laparoscope through a small cut near your bellybutton. The doctor can then insert other instruments through other small cuts to take the biopsy.

You will have stitches where the cuts were made. You may feel sore while you heal, so you will be given pain medicine during and after the operation, and to take at home. There is a small risk of infection or damage to an organ with a laparoscopy. Your doctor will explain the risks before asking you to agree to the procedure.

During surgery to remove the tumour – If you are having a larger operation to remove the tumour, your surgeon may take the tissue sample at that time.

Molecular and genetic testing

Each cell in the human body has about 20,000 genes, which tell the cell what to do and when to grow and divide. Cancer starts because of changes to the genes (known as mutations).

Some people are born with a gene change that increases their risk of cancer (an inherited faulty gene), but most gene changes that cause cancer build up during a person’s lifetime (acquired gene changes).

In some circumstances, your doctors may recommend extra tests to look for acquired gene changes (molecular tests) or inherited gene changes (genetic tests).

Molecular testing

If you have pancreatic cancer, you may be offered extra tests on the biopsy sample known as molecular or genomic testing. This looks for gene changes and other features in the cancer cells that may help your doctors decide which treatments to recommend.

When this information was last reviewed (March 2024), molecular testing for pancreatic cancer is not covered by Medicare. These tests can be expensive, so check what costs are involved and how helpful it would be. If you are having molecular testing as part of a clinical trial, the costs may be covered.

Genetic testing

Your doctor may suspect you have developed pancreatic cancer because you have inherited a faulty gene (e.g. because other members of your family have also had pancreatic cancer). In this case, they may refer you to a family cancer clinic for genetic counselling and extra tests.

These tests are known as genetic or germline tests. The results may help your doctor work out what treatment to recommend and can also provide important information for your blood relatives.

Genetic counselling can help you understand what tests are available to you and what the results mean for you and your family.

Medicare may cover the costs of genetic tests or you may need to pay for them – check this with your treatment team.

Staging pancreatic cancer

The test results will show what type of pancreatic cancer it is, where in the pancreas it is, and whether it has spread. This is called staging, and it helps your doctors work out the best treatment options for your situation.

Pancreatic cancer is commonly staged using the TNM system, with each letter given a number that shows how advanced the cancer is:

- T stands for Tumour and refers to the size of the tumour or how close it is to major blood vessels. It will be given a score of T0–4. The higher the number, the more advanced the cancer is.

- N stands for Nodes and refers to whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes. N0 means the cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes; N1 means the cancer has spread to 1–3 nodes, N2 means the cancer has spread to 4 or more lymph nodes.

- M stands for Metastasis. M0 means the cancer has not spread to other parts of the body; M1 means it has.

The TNM scores are combined to work out the overall stage of the cancer, from stage 1 to stage 4.

If you need help to understand staging, ask someone in your treatment team to explain it in a way that makes sense to you. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Stages of pancreatic cancer

Stage 1 – Cancer is small and found only in the pancreas.

Stage 2 – Cancer is large but has not spread outside the pancreas; or it is small and has spread to a few nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 1–2 cancers are considered early pancreatic cancer. They may also be called resectable, which means surgery to remove the cancer may be an option if you are well enough. About 1 in 5 pancreatic cancers are stage 1–2 when first diagnosed.

Stage 3 – Cancer has grown into nearby major blood vessels or into a lot of nearby lymph nodes.

Some stage 3 cancers are borderline resectable cancers, which means surgery to remove the cancer may be an option if other treatment can shrink the cancer first. Other stage 3 cancers are called locally advanced, which means that surgery cannot remove the cancer, but treatments can relieve symptoms. About 30% of pancreatic cancers are stage 3 when first diagnosed.

Stage 4 – The cancer has spread to more distant parts of the body, such as the liver, lungs or lining of the abdomen. There may or may not be cancer in the lymph nodes.

This is called metastatic cancer. Surgery cannot remove the cancer, but treatments can relieve symptoms. About half of all pancreatic cancers are stage 4 when first diagnosed.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- test results

- the type, stage and location of the cancer

- how the cancer responds to initial treatment

- your medical history

- your age and general health.

As symptoms can be vague or go unnoticed, most pancreatic cancers are not found until they are advanced, which usually means treatment cannot remove all the cancer. If the cancer is diagnosed at an early stage and can be surgically removed, the prognosis may be better.

Discussing your prognosis and thinking about the future can be challenging and stressful. It is important to know that although the statistics for pancreatic cancer can be frightening, they are an average and may not apply to your situation. Talk to your doctor about how to interpret any statistics that you come across.

When pancreatic cancer is advanced, treatment will usually aim to control the cancer for as long as possible, relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. This is known as palliative treatment.

Treatment to remove the cancer

This section gives an overview of treatments used for many stage 1–2 (early) pancreatic cancers and some stage 3 pancreatic cancers.

The treatment options described in this section will be suitable for only about 1 in 5 people with pancreatic cancer, as most people are diagnosed at a later stage. Surgery to remove the cancer, in combination with chemotherapy and possibly radiation therapy, is generally the most effective treatment for early-stage pancreatic cancer. It is important that the surgery is done by a surgeon who is part of a multidisciplinary team in a specialist pancreatic cancer treatment centre.

Surgery to remove the cancer

Surgery to remove the tumour (resection) is the most common treatment for people with early-stage cancer who are in good health. It may also be considered for some stage 3 cancers, usually with chemotherapy (and sometimes radiation therapy) to shrink the tumour first. These stage 3 cancers are known as borderline resectable cancers, which means that surgery alone may or may not be able to remove all of the tumours.

The aim of resection is to remove all the tumour from the pancreas, as well as a margin of healthy tissue. The type of surgery you have will depend on the size and location of the tumour, your general health and your preferences. Your surgeon will talk to you about the most appropriate surgery for you, as well as the risks and any possible complications. Types of surgery include:

Whipple procedure – This treats tumours in the head of the pancreas. Also known as pancreaticoduodenectomy, it is the most common surgery for pancreatic tumours.

Distal pancreatectomy – The surgeon removes only the tail of the pancreas, or the tail and a portion of the body of the pancreas. The spleen is usually removed as well. The spleen helps the body fight infections, so if it is removed you are at higher risk of some types of bacterial infection. Your doctor may recommend vaccinations before and after a distal pancreatectomy.

Total pancreatectomy – When cancer is large or there are many tumours, the entire pancreas and spleen may be removed, along with the gall bladder, common bile duct, part of the stomach and small bowel, and nearby lymph nodes.

If the cancer has spread

During surgery to remove the cancer, the surgeon may find that the cancer has spread around one or more of the major blood vessels in the area or into the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum). This may occur even if you had several scans and tests beforehand.

If this happens, the surgeon will not be able to remove the cancer. However, they may be able to perform procedures (such as a bypass) to relieve some of the symptoms caused by the cancer.

How the surgery is done

Surgery for pancreatic cancer is carried out in hospital under a general anaesthetic. It is difficult surgery and should only be performed by surgeons with a lot of experience in doing this operation. There are 3 main approaches:

- Open surgery – This involves one larger cut in the abdomen so the surgeon can remove the cancer.

- Laparoscopic surgery – This involves several small cuts in the abdomen (belly). It is sometimes called laparoscopic or minimally invasive surgery. The surgeon inserts a long, thin instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) into one of the cuts and uses images from the camera for guidance. The surgeon inserts tools into the other cuts to remove the cancer.

- Robotic-assisted surgery – This is a type of keyhole surgery. The surgeon sits at a control panel to see a 3-dimensional image and moves robotic arms that hold the instruments.

Open surgery is usually the best approach for pancreatic cancer, but keyhole or robotic-assisted surgery may be an option in some circumstances. Talk to your surgeon about what options are available to you. Ask about the risks and benefits of each approach, and check if there are any extra costs.

Having a Whipple procedure

The Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) is a major, complex operation. It has to be done by a specialised pancreatic surgeon or a hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeon.

A Whipple procedure is a long operation. It usually lasts 5–8 hours.

As your surgeon will explain, this surgery is complex and there is a chance of serious problems, such as major bleeding or leaking where the remaining organs have been reconnected.

The surgeon removes the part of the pancreas with the cancer (usually the head); the first part of the small bowel (duodenum); part of the stomach; the gall bladder; and part of the common bile duct.

Then the surgeon reconnects the remaining part of the pancreas, common bile duct and stomach (or duodenum) to different sections of the small bowel to keep the digestive tract working.

Once these organs are reconnected, food, pancreatic juices and bile can continue to flow into the small bowel for the next stage of digestion. Many people need to change their diet after a Whipple procedure.

Most people stay in hospital for 1–2 weeks after surgery, and full recovery takes at least 8–12 weeks. Your team will encourage you to move around and start gentle exercise as soon as you are ready.

What to expect after surgery

While you are recovering after surgery, your health care team will check your progress and help you with the following:

Pain control – You will have some pain and discomfort for several days after surgery. You will be given pain medicines to manage this. If you are in pain when you return home, talk to your doctors about a prescription for pain medicine.

Surgical drain – You may have a thin tube placed in the abdomen to drain fluid into a small bag or bottle. The fluid can then be checked for potential problems. The tube is usually removed after a few days but may be left in for longer. Surgical drains are never permanent.

Drips and tubes – While in hospital, you will have a drip to replace your body’s fluids. At first, you may not be able to eat or drink (nil by mouth). You’ll then be on a liquid diet before slowly returning to normal food. A temporary feeding tube may be put into the small bowel during the operation. This tube provides extra nutrition until you can eat and drink normally again. The hospital dietitian can help you manage changes to eating.

Enzyme supplements – Many people will need to take tablets known as pancreatic enzymes after surgery. These are taken with each meal to help digest fat and protein.

Insulin therapy – Because the pancreas produces insulin, people who have had all or some of their pancreas removed may develop diabetes after surgery and need regular insulin injections (up to 4 times per day). A specialist doctor called an endocrinologist will help you develop a plan for managing diabetes.

Moving around – Your health care team will probably encourage you to walk the day after surgery. They will also provide advice about when you can get back to your usual activity levels.

Length of hospital stay – Most people go home within 2 weeks, but if there are problems, you may need to stay in hospital longer. You may need rehabilitation which is a program to help you recover and regain physical strength, and adapt to changes, after surgery. This may be as an inpatient in a rehabilitation centre or through a home-based rehabilitation program.

What if the cancer returns?

If the surgery successfully removes all of the cancer, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread.

Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Between appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

Unfortunately, pancreatic cancer is difficult to treat and it may come back after treatment. This is known as a recurrence. Most of the time, surgery is not an option if you have a recurrence. Your doctors may recommend other types of treatment with the aim of reducing symptoms and improving quality of life. The next section describes some of these treatments. You may also be able to get new treatments by joining a clinical trial.

Treatment to manage cancer and symptoms

Pancreatic cancer usually has no symptoms in its early stages, so many people are diagnosed when the cancer is advanced.

If the cancer involves nearby organs or blood vessels (locally advanced – some stage 3 cancers) or has spread to other parts of the body (metastasised – all stage 4 cancers), surgery to remove the cancer may not be possible. Instead, treatments will focus on shrinking or slowing the growth of the cancer and relieving symptoms without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment.

Some people think that palliative treatment is only offered at the end of life. However, it can help at any stage of pancreatic cancer. It does not mean giving up hope – rather, it is about managing symptoms and living as fully and comfortably as possible. Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care. Many studies have shown that when palliative care is delivered early it can improve people’s quality of life.

Palliative treatments may include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, either on their own or in combination. These treatments may be used to help manage the cancer and relieve some common symptoms of advanced pancreatic cancer, such as:

- jaundice caused by narrowing of the common bile duct

- ongoing vomiting and weight loss caused by a blockage in the stomach or small bowel

- pain in the abdomen (belly) and middle back.

Many people with advanced pancreatic cancer have digestive problems. For example, a blockage in the pancreatic duct can stop the flow of the digestive enzymes required to break down food. This can be treated with pancreatic enzyme supplements.

Surgery to relieve symptoms

If the tumour is pressing on the common bile duct, it can cause a blockage and prevent bile from passing into the bowel. Bile builds up in the blood, causing symptoms of jaundice, such as yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes; itchy skin; reduced appetite, poor digestion and weight loss; dark urine; and pale stools. If cancer blocks the duodenum (first part of the small bowel), food cannot pass into the bowel and builds up in your stomach, causing nausea and vomiting.

Blockages of the common bile duct or duodenum are known as obstructions. Surgical options for managing these may include:

- stenting – inserting a small tube into the bile duct or duodenum (this is the most common method)

- bypass surgery – connecting the small bowel to the bile duct or gall bladder to redirect the bile around the blockage, and connecting a part of the bowel to the stomach to bypass the duodenum so the stomach can empty properly

- gastroenterostomy – connecting the stomach to the jejunum (middle section of the small bowel)

- venting gastrostomy – connecting the stomach to an opening in the abdomen so waste can be collected in a small bag outside the body.

Sometimes the surgeon may have planned to remove a pancreatic tumour but discovers during the surgery that the cancer has spread. If the tumour cannot be removed, the surgeon may perform one of the operations listed above to relieve symptoms.

Inserting a stent

If the cancer cannot be removed and is pressing on the common bile duct or duodenum, you may need a stent. A stent is a small tube made of either plastic or metal. It holds the bile duct or duodenum open, letting the bile or food flow into the bowel again.

A bile duct stent is also known as a biliary stent. It is usually inserted using an endoscope passed through the mouth, stomach and duodenum until it reaches the bile duct. You may have this procedure as an outpatient or stay in hospital for 1–2 days.

Sometimes the stent needs to be inserted directly through the skin and liver into the bile duct. This is called a PTC (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram).

A duodenum stent is also known as a duodenal stent. It is usually inserted via the mouth using an endoscope.

Symptoms caused by the blockage usually go away over 2–3 weeks. Your appetite is likely to improve and you may gain some weight.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. It is used for pancreatic cancer at various stages. If the cancer is at a stage where it can be removed with surgery, chemotherapy is often used before or after the surgery.

When surgery cannot remove the cancer, chemotherapy can be used as a palliative treatment to slow the growth of the cancer and relieve symptoms. For some stage 3 cancers, chemotherapy may be combined with radiation therapy. This is called chemoradiation.

The chemotherapy drugs are usually given as a liquid through a drip inserted into a vein in the arm (intravenous infusion) or as tablets that you swallow. To avoid damaging the veins in your arm, it may also be given through a tube implanted into a vein (called a port, catheter, central line or PICC line). This will stay in place until all your chemotherapy treatment is over.

You will usually receive treatment as an outpatient (not admitted to hospital). Typically, you will have several courses of treatment, with rest periods of a few weeks in between. Your medical oncologist will assess how the treatment is working based on your symptoms and wellbeing, as well as scans and blood tests. Tell your team about any prescription, over-the-counter or natural medicines you are taking, as these may affect how the chemotherapy works in your body.

"I found chemo a bit daunting – walking into the room with the chairs lined up. But the nurses talked through it with me so I knew what to expect.” CHERYL

Side effects of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can affect healthy cells in the body, which may cause side effects. Some people have few side effects, while others have many. The side effects will depend on the drugs used and the dose. Your medical oncologist and chemotherapy nurses will explain the possible side effects to you, the best ways to manage them and who to contact if you need support.

Side effects of chemotherapy may include feeling very tired (fatigue); feeling sick (nausea); vomiting; mouth ulcers and skin rashes; hair loss; diarrhoea or constipation; flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache and muscle soreness; and poor appetite.

Chemotherapy can also affect the number of cells in your blood. Fewer white blood cells can mean you are more likely to catch infections. Fewer red blood cells (anaemia) can leave you weak and breathless.

Most chemotherapy side effects are temporary and can be managed, so discuss how you are feeling with your treatment team. If you are having chemotherapy as a palliative treatment, your treatment team will help you weigh up the benefits of improving your cancer symptoms against any side effects the chemotherapy is causing.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or injure them so they cannot multiply. The radiation is usually in the form of focused x-ray beams targeted at the cancer. Treatment is painless and carefully planned to do as little harm as possible to healthy body tissue near the cancer.

Chemoradiation – For stage 3 cancers that cannot be removed with surgery (locally advanced cancers), radiation therapy may be given with chemotherapy to slow the growth of the cancer. This is called chemoradiation. For cancers that are at a stage where they can be removed by surgery, chemoradiation may also be used before or after the surgery.

In chemoradiation, the radiation therapy is delivered over several treatments (called fractions). Each fraction delivers a small dose of radiation that adds up to the total treatment dose. Your doctor will let you know your treatment schedule. Many people have treatment as an outpatient once a day, Monday to Friday, for up to 6 weeks.

Each radiation therapy session takes 10–15 minutes. You will lie on a table under a machine called a linear accelerator that delivers radiation to the affected parts of your body. The machine does not touch you, but it may rotate around you to deliver radiation to the area with cancer from different angles. This allows the radiation to target the cancer more precisely and limits the radiation given to surrounding tissues.

Radiation therapy on its own – Radiation therapy may also be used on its own over shorter periods to relieve symptoms. For example, if a tumour is pressing on a nerve or another organ and causing pain or bleeding, a few doses of radiation therapy may shrink the tumour enough to relieve the symptoms.

SBRT – Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is an emerging treatment for pancreatic cancer. It delivers a higher dose of radiation per treatment session over fewer treatment sessions than usual radiation therapy. SBRT is not standard practice for pancreatic cancer but may be a treatment option as part of a clinical trial at some cancer centres.

Linear accelerator (LINAC)

This is a general illustration of a LINAC. The machine used for your treatment may look different. A LINAC is large and is often kept in a separate room. An imaging device, such as a CT scan machine, is usually attached to the LINAC. This helps position you accurately on the couch so the radiation targets the correct area of your body.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, which are mainly related to the area treated. For pancreatic cancer, the treatment is targeted at the abdomen.

Side effects of radiation therapy to the abdomen may include:

- tiredness

- nausea and vomiting

- diarrhoea

- poor appetite

- reflux (when stomach acid flows up into the oesophagus)

- skin irritation.

Most side effects start to improve a few weeks after treatment, but some can last longer or appear later. Late side effects are uncommon, but may include damage to the liver, kidneys, stomach or small bowel. Talk to your radiation oncologist or radiation oncology nurse about ways to manage these side effects.

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy

Other cancer drug treatments include targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Targeted therapy targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading, while immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

A targeted therapy drug called olaparib has been shown to provide some benefit for people with metastatic pancreatic cancer who have the BRCA gene changes. This is only a small number of people with pancreatic cancer. Olaparib is approved for use in Australia but the cost is not yet covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for pancreatic cancer (as at January 2024). Your doctors will be able to provide the latest information about its availability.

So far, other targeted therapy and immunotherapy drugs have had disappointing results for pancreatic cancer, but research is continuing. Talk to your doctor about whether a clinical trial is an option for you.

Managing pain in pancreatic cancer

If pain becomes an issue, you may need a combination of treatments to achieve good pain control. Options for relieving pain may include:

- strong pain medicines such as opioids

- nerve blocks – when anaesthetic or alcohol is injected into nerves

- anticonvulsant medicines to help control nerve pain

- chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy to shrink cancer pressing on nerves

- complementary therapies such as acupuncture, massage and relaxation techniques.

Tell your treatment team if you have any pain, as it is easier to control when treated early. Don’t wait until the pain is severe. Your team can also refer you to a pain specialist or palliative care specialist if needed.

How palliative care can help

The treatment options described in this section are generally part of palliative treatment. Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals work together to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, spiritual and social needs. Specialist palliative care services see people with more complex needs and can also advise other health professionals.

Contacting a specialist palliative care service soon after diagnosis gives them the opportunity to get to know you, your family and your circumstances. You can ask your treating doctor for a referral.

How palliative care works

Palliative care is an important part of care for many people with pancreatic cancer. Palliative care may be helpful at any time after diagnosis and is often delivered alongside active cancer treatment to help maintain your quality of life.

When to start – Palliative care is useful at all stages of advanced cancer. Contacting a palliative care team after a diagnosis of advanced pancreatic cancer can help you work out when is best to start palliative treatment.

Symptom relief – Palliative treatment can help you manage symptoms related to the cancer or its treatment, such as fatigue, pain or nausea.

Who provides care – The palliative care team is made up of people with different skills to help you with a range of issues. Care may be led by a GP, nurse practitioner or community nurse, or a specialist palliative care team.

Support services – The palliative care team will help you work out how to live in the most fulfilling way you can. They can refer you to organisations and services that can assist with practical, financial and emotional needs.

Family and carers – If you agree, the palliative care team will involve your family and carers in decisions about your care. They can also provide them with practical and emotional support.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Palliative Care’

Download our booklet ‘Living with Advanced Cancer’

Listen to our podcast series ‘The Thing About Advanced Cancer’

Managing your diet and nutrition

Pancreatic cancer and its treatment can affect your ability to eat, digest and absorb essential nutrients.

This section explains some common diet and nutrition problems, and how to manage them.

During and after treatment, it’s important to make sure you are eating and drinking enough to maintain your weight and avoid malnutrition or dehydration. Different foods can affect people differently, so you will need to experiment to work out which foods cause problems for you. Most people will also have to take a special tablet to help with digestion.

Coping with the changes

Changes to the way you eat may make you feel anxious, particularly when you know eating well is important. Some people find it difficult to cope emotionally with the changes to how and what they can eat. Finding ways to enjoy your meals can help to improve your quality of life. It may help to talk about how you feel with your family and friends. You can also call Cancer Council 13 11 20 – our experienced health professionals may be able to arrange for you to speak with a Cancer Connect volunteer who has had a similar cancer experience.

Some people find that complementary therapies such as relaxation, meditation and acupuncture help them cope with diet and nutrition problems. Always tell your cancer care team if you are using or would like to try any complementary therapies.

Download our booklet ‘Emotions and Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Seeing a dietitian

If you have ongoing problems with food and eating, talk to a dietitian. Dietitians are experts in nutrition who can give you specialist advice on how to cope with nutrition-related problems and eating difficulties throughout different phases of the disease. A dietitian can prepare eating plans for you and give you advice about nutritional supplements.

Dietitians work in all public and most private hospitals. There may be a dietitian connected to your cancer treatment centre – check with your specialist or cancer care coordinator. Dietitians Australia can also help you find an accredited practising dietitian who works in your area and specialises in cancer.

If your GP refers you to a dietitian, you may be eligible for a Medicare rebate to help cover the cost. If you have private health insurance, you may be able to claim part of the cost.

Nutritional supplements

If you can’t eat a balanced diet or are losing too much weight, your doctor or dietitian may suggest nutritional supplements such as Sustagen, Ensure, Fortisip or Resource. These provide energy, protein and other nutrients that can help you maintain your strength.

A dietitian can recommend the right nutritional supplement for you and let you know where to buy it and how much to use. Nutritional supplements should be taken in addition to the foods you are able to eat, and are best used as snacks between meals.

Supplements are available as:

- ready-made drinks, bars, puddings and custards

- powders to mix with milk or water, or to sprinkle on food.

Enzyme replacement therapy

The pancreas produces digestive enzymes to help break down food. When you have pancreatic cancer, or have had pancreatic surgery, your body may not be able to make enough of these digestive enzymes. This will affect your ability to digest food, particularly fat and protein, and to absorb vital nutrients.

This is often called pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI). Signs of PEI include abdominal pain; bloating and excessive wind; diarrhoea or pale, oily stools that are frothy, loose and difficult to flush; and weight loss.

To help prevent these symptoms, your doctor will prescribe pancreatic enzymes (e.g. CREON). This therapy may be called pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy or PERT. Sometimes, acid-suppressing medicines are also used. The PERT dose will be adjusted depending on your symptoms and diet. It may take time to get this balance right. A dietitian can help you and your doctor work out the correct dose of PERT.

Taking enzyme supplements

- Take enzyme capsules with water and the first mouthful of food to ensure adequate mixing. With larger meals or meals that take longer to consume (more than 15–20 minutes), you may also need to take them halfway through the meal.

- Always take enzymes when having food or drink that contains fat or protein. Slightly higher doses may be needed with high-fat meals (e.g. fried foods, pizza). You don’t need to take enzymes for simple carbohydrates that digest easily (e.g. fruit, fruit juice, black tea, coffee).

- Take enzyme supplements as prescribed. Do not change the dose without first talking to your doctor or dietitian.

Tips for maintaining your weight

During and after treatment for pancreatic cancer, changes to what you can eat, how you feel about eating and how your body absorbs food can lead to unplanned weight loss. This can cause a loss of strength, increase fatigue and affect how you cope with treatment. The tips below may help.

Have regular meals – Eat small meals frequently (e.g. every 2–3 hours), and have a regular eating pattern rather than waiting until you’re hungry. Keep ready-to-eat food on hand for when you are too tired to cook (e.g. tinned fruit, yoghurt, frozen meals).

Choose nourishing food and drink – Ensure that meals and snacks are nourishing and include protein such as meat, chicken, fish, dairy products, legumes (e.g. lentils, chickpeas), eggs, tofu, nuts and nut butters. Choose nourishing drinks (e.g. milk, smoothies). A dietitian may also suggest nutritional supplement drinks.

Load up your food – There are different ways to add extra kilojoules to your food:

- Add milk powder to cereals, sauces, mashed vegetables, soup, drinks, egg dishes and desserts.

- Add cheese to sauces, soup, baked beans, vegetables, casseroles, salads and egg dishes.

- Add sugar, honey or golden syrup to cereals, porridge or drinks.

- Use a powdered nutritional supplement recommended by your dietitian

Adjust to taste changes – You may find your sense of taste changes after treatment. If food tastes bland, add extra flavouring such as herbs, lemon, lime, ginger, garlic, honey, chilli, pepper, Worcestershire sauce, soy sauce or pickles. Eating moist fruits such as berries or sucking boiled lollies can help if you have a bitter or metallic taste in your mouth.

Avoid strong food smells – If food smells bother you, ask family or friends to do the cooking. You may also prefer cold food or food at room temperature without a strong smell.

Talk to a dietitian – A dietitian can help if you are finding it hard to work out the right foods to help gain weight. You should also check with a dietitian before cutting out particular foods.

Follow your appetite – It’s okay to focus on eating foods that you enjoy. Gaining or maintaining weight is more important at the moment than avoiding extra fat and sugar.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting can occur because of the cancer or its treatment. For some people, just the thought of treatment or eating or the smell of food can make them feel unwell. There is a range of anti-nausea medicines (antiemetics) that you can take regularly to control symptoms. If the one you are prescribed doesn’t work, let your doctor or nurse know so you can try another medicine.

Also advise your treatment team if vomiting lasts for more than a day or if you can’t keep any fluids down, as you may become dehydrated. Signs of dehydration include a dry mouth, dark urine, dizziness and confusion.

If you have persistent vomiting, the duodenum (the first part of the small bowel) may be blocked, so see your doctor as soon as possible. You may need surgery to clear the blockage.

Coping with nausea

- Eat and drink slowly. Chew food well.

- Some anti-nausea medicines need to be taken half an hour before meals – ask your doctor about this.

- Try to eat a little bit at regular intervals – not eating or skipping meals can make nausea worse.

- Suck on boiled lollies. Try peppermint-flavoured or lemon-flavoured lollies.

- Avoid strong odours and cooking smells.

- Snack on bland foods such as dry crackers or toast.

- Drink ginger beer, ginger ale or ginger tea, or suck on candied ginger.

Steps to recovery after vomiting

- Take small sips

Don’t try to force down food. Sip small amounts of liquid as often as possible. Try flat dry ginger ale, cold flat lemonade, weak cordial, or cold apple or orange juice. - Introduce nourishing fluids

If the vomiting has stopped but you still feel sick, slowly introduce more nourishing fluids. Start with cold or iced drinks. Prepare milk or fruit drinks with some water so they are not too strong. You can also try diluted fluids such as clear broth or weak tea. - Start solid food

Next, try to eat small amounts of solid foods, such as plain dry biscuits, toast or bread with honey or jam, or smooth congee (rice porridge). Stewed fruits and yoghurt are also good. Aim to eat small amounts of food often, rather than 3 large meals a day. - Return to a normal diet

As soon as you can, increase your food intake until you are eating a normal, balanced diet. Limit rich foods, such as fatty meats or full-cream dairy products. Your doctor or dietitian may suggest adding extra nourishment (such as nutritional supplements) on your good days to make up for the days you can’t eat properly.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is when your bowel motions become loose, watery and frequent. You may also get abdominal cramping, wind and pain.

Pancreatic cancer treatments, other medicines, infections, reactions to certain foods, and anxiety can all cause diarrhoea.

If the tips listed below don’t work for you, talk to your doctor about trying anti-diarrhoea medicine.

You should also let your doctor know if your stools are pale in colour, oily, very smelly, float and are difficult to flush, or you notice an oily film floating in the toilet. This may be a sign that you do not have enough pancreatic enzymes. You may need to start pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) or adjust your dose.

Managing diarrhoea

- Drink plenty of liquids (e.g. water, fruit juice, weak cordial) to replace lost fluids.

- Try lactose-reduced milk or soy milk if you develop a temporary intolerance to the sugar (lactose) in milk. This can sometimes occur when you have diarrhoea. Small amounts of hard cheese and yoghurt are usually okay.

- Avoid alcohol and limit caffeine and spicy foods as these can all make diarrhoea worse.

- Always let your treatment team know if you notice any changes to your bowel habits.

Diabetes

Insulin is a hormone that controls the amount of sugar in the blood. Diabetes, or high blood sugar levels, can occur if your pancreas is not making enough insulin. This is why some people develop diabetes shortly before pancreatic cancer is diagnosed (when the cancer is affecting how much insulin the pancreas can make) or soon after surgery (when some or all of the pancreas has been removed).

The way diabetes is managed varies from person to person but often includes both dietary changes and insulin injections. Sometimes medicines are given as tablets that you swallow.

Your GP can help you manage the condition, but you may be referred to an endocrinologist, a specialist in hormone disorders. You may also be referred to a dietitian for help with your diet and to a diabetes specialist nurse, who can help to coordinate your care and provide support.

Coping with diabetes

- Eat small meals and snacks regularly to help control blood sugar levels.

- Talk to your endocrinologist or GP about medicines to help control the diabetes.

- If you are taking diabetes medicine, include high-fibre carbohydrate foods at every meal to avoid low blood sugar levels. Wholegrain breads and cereals, vegetables and fruit are all

suitable foods. - Talk to your doctors and dietitian for more information about diabetes.

- Visit the National Diabetes Services Scheme or call them on 1800 637 700. They can provide advice on managing diabetes.

Living with pancreatic cancer

Life after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer can present many challenges.

It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes. Establish a new daily routine that suits you and the symptoms you’re coping with. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

For some people, the cancer goes away with treatment. Other people will have ongoing treatment to manage symptoms. You are likely to feel a range of emotions about having pancreatic cancer. Talk to your treatment team if you are finding it hard to manage your emotions. Cancer Council 13 11 20 can also provide you with some strategies for coping with the emotional and practical aspects of living with pancreatic cancer.

When the cancer is advanced

If you are told that you have advanced pancreatic cancer, it may bring up different emotions and reactions. You may not know what to say or think; you may feel sadness, anger, disbelief or fear. There is no right or wrong way to react. Give yourself time to take in what is happening and accept that some days will be easier than others.

Many people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer think about what will happen to them if or when the disease progresses. You may question how much more time you have to live and begin going over your life and what it has meant for you. These thoughts are natural in this situation.

You might find it helpful to talk to your GP and the palliative care doctors and nurses about what you are going through. They can explain what to expect and how any symptoms will be managed.

In addition to doctors and nurses, the specialist palliative care team may include a social worker, counsellor or spiritual care practitioner (pastoral carer), and you can talk to them about how you are feeling.

If you are not already in contact with a palliative care service, talk to your cancer specialist about a referral.

For information and insights that can help you navigate through the challenges of living with advanced cancer, listen to Cancer Council’s podcast series ‘The Thing About Advanced

Cancer’.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them

on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.