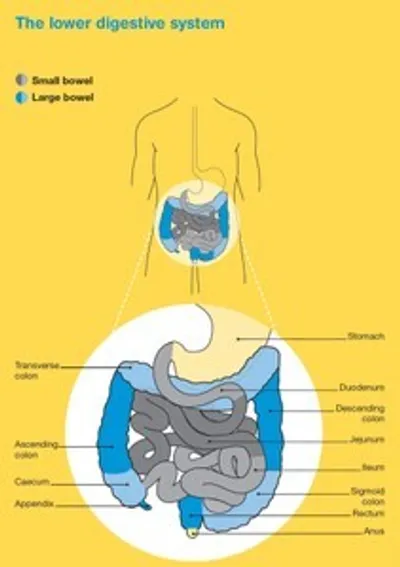

The small bowel

The small bowel (small intestine) is a long tube that absorbs nutrients from food and carries food between your stomach and large bowel (colon).

The small bowel has three parts:

- duodenum – the first section of the small bowel; receives broken-down food from the stomach

- jejunum – the middle section of the small bowel

- ileum – the final and longest section of the small bowel; transfers waste matter to the large bowel.

What is small bowel cancer?

Small bowel cancer (also called small intestine cancer) occurs when cells in the small bowel becomes abnormal and keep growing and form a mass or lump called a tumour. The type is defined by the particular cells that are affected.

Malignant (cancerous) tumours have the potential to spread to other parts of the body through the blood stream or lymph vessels and form another tumour at a new site. This new tumour is known as secondary cancer or metastasis.

Types of small bowel cancer

The most common types include:

Adenocarcinoma – These start in epithelial cells (which release mucus) that line the inside of the small bowel, often in the duodenum.

Sarcoma – These start in connective tissue (which support and connect all the organs and structures of the body). Gastro-intestinal stromal tumours (GIST) start in nerve cells anywhere in the small bowel. Leiomyosarcoma starts in muscle tissues in the wall of the small bowel, often in the ileum.

Neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumours (NETs) – These form in neuroendocrine cells inside the small bowel, often in the ileum. The neuroendocrine system is a network of glands and nerve cells that make hormones and release them into the bloodstream to help control normal body functions.

Lymphoma – These form in lymph tissue (part of the immune system which protects the body) in the small bowel, often in the jejunum. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma starts in lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell.

How common is small bowel cancer?

Small bowel cancer is rare. About 530 Australians are diagnosed each year (this is about 2 cases per 100,000 people). It is more likely to be diagnosed in men than women, and people aged over 60 years.

What are the symptoms and the risk factors?

Small bowel cancer can be difficult to diagnose, and symptoms may be vague and caused by other conditions.

Symptoms may include:

- abdominal (tummy) pain

- unexplained weight loss

- a lump in the abdomen

- blood in the stools or on the toilet paper

- changes in bowel habits, including diarrhoea or constipation

- feeling sick (nausea) or vomiting

- tiredness and weakness, caused by a low red blood cell count (anaemia)

- yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice).

Small bowel neuroendocrine tumours can develop slowly and may not cause symptoms. If you do have symptoms it will depend on where in the body the tumour is and whether the tumour cells are producing hormones.

Some neuroendocrine tumours that are more advanced produce excess hormones (such as serotonin) that can cause a group of symptoms known as carcinoid syndrome. Symptoms may include facial flushing, diarrhoea, wheezing and, rarely, carcinoid heart disease leading to shortness of breath.

More information is available from NeuroEndocrine Cancer Australia.

What are the risk factors?

The cause of small bowel cancer is not known in most cases. However, there are several risk factors:

Genetic factors – Some rare, inherited diseases can put people more at risk of small bowel cancer. These include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) and cystic fibrosis (CF). Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN 1) may increase the risk of small bowel neuroendocrine tumours.

Other factors – Some small bowel cancers may be linked to Crohn’s disease and coeliac disease. Eating large amounts of animal fat and protein, especially processed meat and red meat, might increase the risk of small bowel cancer.

How is small bowel cancer diagnosed?

If your doctor thinks that you may have small bowel cancer, they will perform a physical examination and carry out certain tests.

If the results suggest that you may have small bowel cancer, your doctor will refer you to a specialist who will carry out more tests. These may include:

Blood, urine and iFOBT tests

Blood tests – including a full blood count to measure your white blood cells, red blood cells, platelets, and liver function tests to measure chemicals that are found or made in your liver. You may also have a chromogranin A (CgA) blood test to help diagnose a carcinoid or other neuroendocrine tumour.

Urine test – to examine if there are any cancer ‘waste’ products excreted into the urine.

Immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) – to examine a stool sample for traces of blood.

Endoscopy and capsule endoscopy

Endoscopy – a procedure where a flexible tube with a camera on the end (endoscope) is inserted under sedation down the throat into the stomach to view your gut.

Capsule endoscopy – a procedure where you swallow a small capsule that contains a tiny camera that takes pictures of your digestive tract that are then transmitted to a recorder you wear around your waist. The camera is passed out in your stools about 24 hours later.

CT (computerised tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans

Special machines are used to scan and create pictures of the inside of your body. Before the scan you may have an injection of dye (called contrast) into one of your veins, which makes the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will need to lie still on an examination table.

For a CT scan the table moves in and out of the scanner which is large and round like a doughnut; the scan itself takes about 10 minutes.

For an MRI scan the table slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends; the scan takes a little longer, about 30–90 minutes to perform. Both scans are painless.

PET (positron emission tomography) scan

Before the scan you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) solution. Many cancer cells will show up brighter on the scan. You will be asked to sit quietly for 30–90 minutes to allow the glucose to move around your body, and the scan itself will take around 30 minutes to perform. Sometimes a Dotatate-PET scan will be needed to find and diagnose neuroendocrine tumours. In this test you will be injected with a small amount of a radioactive drug call Dotatate rather than a radioactive glucose.

Biopsy

A biopsy is the removal of some tissue from the affected area for examination under a microscope. In the small bowel, a biopsy can be done during an endoscopy or if it can’t be reached a surgical biopsy is done under general anaesthesia. The surgeon will cut through the skin and use a tiny instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) to view the affected area and use another instrument to take a tissue sample.

Barium x-ray

Also called upper GI series with small bowel follow-through, you will be given a chalky barium liquid to drink which coats the inside of the bowel and can show any signs of cancer when an x-ray is taken. X-rays may be taken over a few hours as the barium travels to the end of the small bowel.

Finding a specialist

Rare Cancers Australia have a directory of health professionals and cancer services across Australia.

Visit The Australia and New Zealand Sarcoma Association (ANZSA) for a directory of specialists in sarcoma care and treatment.

Visit NeuroEndocrine Cancer Australia for a directory of specialists in NET care and treatment.

Treatment for small bowel cancer

You will be cared for by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of health professionals during your treatment for small bowel cancer.

These may include a surgeon, radiation oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of radiation therapy), medical oncologist (to prescribe and coordinate a course of drug therapies which includes chemotherapy and immunotherapy), gastroenterologist (to treat disorders of the digestive system), nurse and allied health professionals such as a dietitian, social worker, psychologist or counsellor, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Discussion with your doctor will help you decide on the best treatment for your cancer depending on:

- the type of cancer you have

- where it is in your body

- whether or not the cancer has spread (stage of disease)

- your age, fitness and general health

- your preferences.

The main treatments for small bowel cancer include surgery and chemotherapy. Often medications are used that block cancer cells from secreting hormones and chemicals. These treatments can be given alone or in combination.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for small bowel cancer (adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and neuroendocrine tumours), especially for people with early-stage disease who are in good health. It is not usually recommended for lymphomas in the small bowel – these are commonly treated with radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

The way the surgery is done depends on the location and stage of the tumour. Your doctor will advise which approach is most suitable for you.

Open surgery – This involves one long cut down the middle of your abdomen (tummy).

Keyhole surgery – This involves several small cuts in the abdomen. A thin tube with a light and camera (laparoscope) is passed through one of the cuts and long, thin instruments are inserted through other small cuts to remove the cancer.

Surgical procedures

Resection – Surgical removal of part of the small bowel that contains cancer; surrounding lymph nodes and nearby organs (stomach, large bowel, gall bladder) may also be removed during the procedure.

- Right Hemicolectomy – removes the right side of the large bowel and the end of the ileum.

- Whipple procedure – removes the pancreas, the duodenum, the gall bladder and bile duct. Also called pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Bypass – Surgical connection to allow digested food in the small bowel to go around the cancer if it is blocking the bowel and cannot be removed.

If part of the bowel is removed during surgery, the surgeon will usually join it back together. This join is called an anastomosis. If this isn’t possible, you may need a stoma where the end of the intestine is brought through an opening (the stoma) made in your abdomen to allow faeces to be removed from the body and collected in a bag. This procedure is called an ileostomy if made from the small bowel. The stoma may be temporary (where the operation is reversed later) or permanent if it is not able to be rejoined.

Living with a stoma

If there is a chance you could need a stoma, the surgeon will refer you to a stomal therapy nurse before surgery. Stomal therapy nurses are registered nurses with special training in stoma care. They can answer questions about your surgery and recovery, and give you information about adjusting to life with a stoma. For more details, visit the Australian Association of Stomal Therapy Nurses or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (sometimes just called “chemo”) is the use of drugs to kill or slow the growth of cancer cells. You may have one chemotherapy drug, or a combination of drugs. This is because different drugs can destroy or shrink cancer cells in different ways.

Your treatment will depend on your situation and the type of cancer you have. Chemotherapy is often used to treat lymphomas in the small bowel. Your medical oncologist will discuss your options with you.

Chemotherapy is given through a drip into a vein (intravenously) or as a tablet that is swallowed. It is commonly given in treatment cycles which may be daily, weekly or monthly. For example, one cycle may last three weeks where you have the drug over a few hours, followed by a rest period before starting another cycle. The length of the cycle and number of cycles depends on the chemotherapy drugs being given.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy or biological therapy uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. It uses materials made either by the body or in a laboratory to improve immune system function. There are different types of immunotherapy available so talk to your doctor about what might be appropriate for you.

External beam radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also known as radiotherapy) uses high energy rays to destroy cancer cells, where the radiation comes from a machine outside the body. It may be used for small bowel cancer:

- before or after surgery, to destroy any remaining cancer cells and stop the cancer coming back

- if the cancer can’t be removed with surgery

- if the cancer comes back in a limited way, such as only in your abdominal lymph glands.

Radiation therapy can shrink the cancer down to a smaller size. This may help to relieve symptoms such as pain or blood loss.

A course of radiation therapy needs to be carefully planned. During your first consultation session you will meet with a radiation oncologist who will arrange a planning session. At the planning session (known as CT planning or simulation) you will need to lie still on an examination table and have a CT scan in the same position you will be placed in for treatment.

The information from the planning session will be used by your specialist to work out the treatment area and how to deliver the right dose of radiation. Radiation therapists will then deliver the course of radiation therapy as set out in the treatment plan.

Radiation therapy does not hurt and is usually given in small doses over a period of time to minimise side effects.

Clinical trials

Your doctor or nurse may suggest you take part in a clinical trial. Doctors run clinical trials to test new or modified treatments and ways of diagnosing disease to see if they are better than current methods. For example, if you join a randomised trial for a new treatment, you will be chosen at random to receive either the best existing treatment or the modified new treatment. Over the years, trials have improved treatments and led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with cancer.

You may find it helpful to talk to your specialist, clinical trials nurse or GP, or to get a second opinion. If you decide to take part in a clinical trial, you can withdraw at any time.

For more information, visit Australian Cancer Trials or the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG).

For information on sarcoma clinical trials contact the Australia and New Zealand Sarcoma Association (ANZSA).

For information on NET clinical trials contact NeuroEndocrine Cancer Australia.

For information on lymphoma clinical trials contact the Australian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG).

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Clinical Trials and Research’

Complementary therapies

Complementary therapies tend to focus on the whole person, not just the cancer, and are designed to be used alongside conventional medical treatments (such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy). They can increase your sense of control, decrease stress and anxiety, and improve your mood.

Some Australian cancer centres have developed “integrative oncology” services where evidence-based complementary therapies are combined with conventional treatments to create patient-centred cancer care that aims to improve both wellbeing and clinical outcomes.

Some complementary therapies and their clinically proven benefits are listed below:

- acupuncture – reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; improves quality of life

- aromatherapy – improves sleep and quality of life

- art therapy, music therapy – reduce anxiety and stress; manage fatigue; aid expression of feelings

- counselling, support groups – help reduce distress, anxiety and depression; improve quality of life

- hypnotherapy – reduces pain, anxiety, nausea and vomiting

- massage – improves quality of life; reduces anxiety, depression, pain and nausea

- meditation, relaxation, mindfulness – reduce stress and anxiety; improve coping and quality of life

- qi gong – reduces anxiety and fatigue; improves quality of life

- spiritual practices – help reduce stress; instil peace; improve ability to manage challenges

- tai chi – reduces anxiety and stress; improves strength, flexibility and quality of life

- yoga – reduces anxiety and stress; improves general wellbeing and quality of life.

Let your doctor know about any therapies you are using or thinking about trying, as some may not be safe or evidence-based.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Complementary Therapies’

Alternative therapies are therapies used instead of conventional medical treatments. These are unlikely to be scientifically tested and may prevent successful treatment of the cancer. Cancer Council does not recommend the use of alternative therapies as a cancer treatment.

Nutrition and exercise

If you have been diagnosed with small bowel cancer, both the cancer and treatment will place extra demands on your body. Research suggests that eating well and exercising can benefit people during and after cancer treatment.

Eating well and being physically active can help you cope with some of the common side effects of cancer treatment, speed up recovery and improve quality of life by giving you more energy, keeping your muscles strong, helping you maintain a healthy weight and boosting your mood.

You can discuss individual nutrition and exercise plans with health professionals such as dietitians, exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Exercise for People Living with Cancer’

Side effects of treatment

All treatments can have side effects. The type of side effects that you may have will depend on the type of treatment and where in your body the cancer is. Some people have very few side effects and others have more. Your specialist team will discuss all possible side effects, both short and long-term (including those that have a late effect and may not start immediately), with you before your treatment begins.

One issue that is important to discuss before you undergo treatment is fertility, particularly if you want to have children in the future.

Download our booklet ‘Fertility and Cancer’

Common side effects may include:

Surgery – Bleeding, damage to nearby tissue and organs (including nerves), pain, infection after surgery, blood clots, weak muscles (atrophy), lymphoedema.

Radiation therapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, bowel issues such as diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and excess wind, bladder issues, skin problems, lymphoedema, loss of fertility.

Chemotherapy – Fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, bowel issues such as constipation or diarrhoea, hair loss, mouth sores, skin and nail problems, increased chance of infections, loss of fertility.

After treatment for small bowel cancer (especially surgery), you may need to adjust to changes in the digestion and absorption of food, or bowel function. These changes may be temporary or ongoing, and may require specialised help. If you experience problems, talk to your GP, specialist doctor, specialist nurse or dietitian.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

Once your treatment has finished, you will have regular check-ups to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. Ongoing surveillance for small bowel cancer involves a schedule of ongoing scans and physical examinations. How often you will need to see your doctor will depend on the level of monitoring needed for the type and stage of your cancer. Let your doctor know immediately of any health problems between visits.

Some cancer centres work with patients to develop a “survivorship care plan” which usually includes a summary of your treatment, sets out a clear schedule for follow-up care, lists any symptoms to watch out for and possible long-term side effects, identifies any medical or psychosocial problems that may develop and suggests ways to adopt a healthy lifestyle going forward. Maintaining a healthy body weight, eating well and being physically active are all important.

If you don’t have a care plan, ask your specialist for a written summary of your cancer and treatment and make sure a copy is given to your GP and other health care providers.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people small bowel cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. This is why it’s important to have regular check-ups.

If the cancer does come back, treatment will depend on where the cancer has returned to in your body and may include a mix of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

In some cases of advanced cancer, treatment will focus on managing any symptoms, such as pain, and improving your quality of life without trying to cure the disease. This is called palliative treatment. Palliative care can be provided in the home, in a hospital, in a palliative care unit or hospice, or in a residential aged care facility. Services vary, because palliative care is different in each state and territory.

When cancer is no longer responding to active treatment, it can be difficult to think about how and where you want to be cared for towards the end of life. However, it’s essential to talk about what you want with your family and health professionals, so they know what is important to you. Your palliative care team can support you in having these conversations.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, as counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people are able to get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Ask your doctor if you are eligible. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council

13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call 13 11 14.