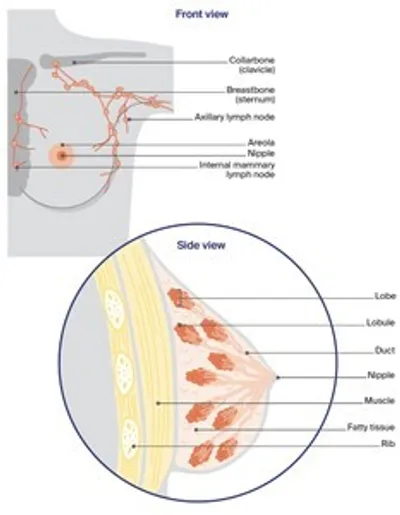

The breasts

The breasts sit on top of the upper ribs and a large chest muscle. They cover the area from the collarbone (clavicle) to the armpit (axilla) and across to the breastbone (sternum). Some breast tissue extends into the armpit and is called the axillary tail.

Female breasts are mostly made up of:

- lobes – each breast has 12–20 sections called lobes

- lobules – each lobe contains glands that can produce milk; these milk glands are called lobules or glandular tissue

- ducts – the lobes and lobules are connected by fine tubes called ducts; the ducts carry milk to the nipples when breastfeeding

- fatty/fibrous tissue – all breasts contain some fatty or fibrous tissue (including connective tissue called stroma), no matter their size.

Most younger women have dense or thicker breasts because they contain more lobules than fat. Male breasts have ducts and fatty/fibrous tissue. They usually contain no, or only a few, lobes and lobules.

The lymphatic system – The lymphatic system is an important part of the immune system, which protects against disease and infection. The lymphatic system drains excess fluid from body tissues into the blood. It is made up of a network of thin tubes called lymph vessels. These vessels connect to groups of small, bean-shaped lymph nodes (or glands).

There are lymph nodes throughout the body, including in the armpits, neck, abdomen, groin and chest (near the breastbone). The first place breast cancer cells usually spread to is the lymph nodes in the armpits (axillary lymph nodes) or to the lymph nodes near the breastbone (internal mammary lymph nodes).

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about breast cancer are below.

What is breast cancer?

Breast cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in the breast. It usually starts in the lining of the breast ducts or lobules, and can grow into cancerous (malignant) tumours. Most breast cancers are found when they are invasive. This means that the cancer has spread from the breast ducts or lobules into the surrounding breast tissue. Invasive breast cancer can be early, locally advanced or advanced (metastatic). Advanced breast cancer is when cancer cells have spread (metastasised) outside the breast and nearby lymph nodes to other parts of the body. About 5% of cancers are advanced when breast cancer is first diagnosed.

How common is breast cancer?

About 20,700 people are diagnosed with breast cancer in Australia every year.

Women – In Australia, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women (apart from common skin cancers), with 1 in 8 women diagnosed by age 85. Young women can get breast cancer, but it is more common over the age of 40, and the risk increases with age. In rare cases, pregnant or breastfeeding women can get breast cancer. See a doctor about any persistent lump noticed during pregnancy.

Men – About 220 men (most aged over 60) are diagnosed with breast cancer each year. It is treated in the same way as for women. For more information, visit Breast Cancer in Men, or Breast Cancer Network Australia.

Transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse – Any transgender woman taking medicines to boost female hormones and lower male hormones has a higher breast cancer risk (compared with a man). A transgender man who has had breasts removed in a nipple-sparing mastectomy can still get breast cancer, although the risk is low.

Does breast cancer run in families?

Most people with breast cancer do not have a strong family history, but a small number may have inherited a gene fault (also called a mutation) that increases their breast cancer risk.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 – These are the most common gene mutations linked to breast cancer. Women in families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 are at increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers. Men in families with BRCA2 may be at increased risk of breast and prostate cancers.

Other genes linked to breast cancer – These include ATM, BARD1, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53. More gene mutations linked to breast cancer are being found all the time. A genetic test called an extended gene panel test checks for the most common types of genes linked with breast cancer.

To find out if you have inherited a gene mutation, talk to your doctor or breast cancer nurse about visiting a family cancer clinic or genetic oncologist. Your specialist may also be able to order genetic tests. In particular, women diagnosed before 40 years, those with triple negative breast cancer diagnosed before 60 years, and men with breast cancer should ask for a referral. Genetic testing is covered by Medicare for some, but not all, people; ask your doctor about this.

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

Many factors can increase your risk of breast cancer, but they do not mean that you will develop it. You can also have none of the known risk factors and still get breast cancer. If you are worried, speak to your doctor. For more information, see Cancer Australia or Peter Mac.

Personal factors

- Being female is the biggest risk factor – 99% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed in women.

- Risk increases with age for both men and women.

- More than 3 in 4 breast cancer cases are in women over the age of 50. Free breast screening is available.

- Dense breast tissue (as seen on a mammogram) increases your risk.

- Breast implants do not increase breast cancer risk, but some implants are linked with a type of cancer called lymphoma. Visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration for more information.

Lifestyle factors

- Being overweight or gaining weight after menopause. Losing weight to a healthy range can lower this.

- Drinking alcohol – the more that you drink, the higher your risk. If you choose to drink, the Australian alcohol guidelines suggest you drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week, and no more than 4 standard drinks on any one day.

- Not getting enough exercise or not being physically active.

- Smoking tobacco.

Family history

- About 5–10% of breast cancers are due to an inherited breast cancer gene such as BRCA1 or BRCA2.

- Most people with breast cancer do not have a strong family history. However, having several close relatives (e.g. mother, sister, aunt) on the same side of the family who have had breast or ovarian cancer may increase your risk.

- Several close relatives on the same side of the family with prostate or pancreatic cancer may increase your risk.

Hormonal factors

- Long-term use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) containing both oestrogen and

progesterone. - Taking the oral contraceptive pill (the pill) for a long time may slightly increase the risk.

- You or your mother using diethylstilboestrol (DES) during pregnancy.

- Transgender women taking gender-affirming hormones for more than 5 years.

Medical history

- Having been previously diagnosed with breast cancer, LCIS or DCIS.

- Some non-cancerous conditions of excessive growth of breast cells (atypical ductal hyperplasia or ADH).

- Having radiation therapy to the chest area for Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Males with a rare genetic syndrome called Klinefelter syndrome. Those with this syndrome have 3 sex chromosomes (XXY) instead of the usual 2 (XY).

Reproductive factors

- Never having given birth to a child.

- Starting your first period (menstruating) before the age of 12.

- Being older than age 30 when you gave birth to your first child.

- Never having breastfed a child.

- Going through menopause after the age of 55.

What are the different types of breast conditions and breast cancers?

Non-invasive breast conditions

These are conditions where the abnormal cells have not invaded nearby tissues. Also called carcinoma in situ.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

- abnormal cells in the breast ducts

- may develop into invasive breast cancer

- treatment is similar to that for invasive breast cancer, but chemotherapy is not used

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)

- abnormal cells in the breast lobules

- does not develop into cancer but increases the risk of developing cancer, including in the other breast

- usually treated with surgery, and hormone therapy may be used

- more regular mammograms or other scans needed to check for any changes

Invasive breast cancers

Invasive means that the cancer cells have grown and spread beyond the breast ducts/lobules and into the surrounding tissue. The 2 main types of invasive breast cancer are named after the breast area that they start in.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC)

- starts in the breast ducts

- about 80% of breast cancers are IDC

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC)

- starts in the breast lobules

- about 10% of breast cancers are ILC

Less common breast cancers include inflammatory breast cancer, medullary carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, Paget disease of the nipple (or breast) and papillary carcinoma. Phyllodes tumour is a rare breast condition that may be benign or malignant.

If invasive breast cancer spreads beyond the breast tissue and the nearby lymph nodes, it is called advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

What are the symptoms?

Breast cancer sometimes has no symptoms, so regular checks are important for women aged 40 and over. Breast changes may not mean cancer, but see a doctor if you notice:

- a lump, lumpiness or thickening, especially in just one breast

- a change in the size or shape of the breast or swelling

- a change to the nipple – change in shape, crusting, sores or ulcers, redness, pain, a clear or bloody discharge, or a nipple that turns in (inverted nipple) when it used to stick out

- a change in the skin – dimpling or indentation, a rash or itchiness, scaly appearance, unusual redness or other colour changes

- swelling or discomfort in the armpit or near the collarbone

- ongoing, unusual breast pain not related to your period.

Which health professionals will I see?

You may be sent for tests after a screening mammogram, or your general practitioner (GP) may arrange tests to check your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out cancer, you will usually be referred to a specialist or breast clinic. If breast cancer is diagnosed, you will see a breast surgeon or a medical oncologist, who will talk to you about your treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care. You may not see all members of the MDT.

Health professionals you may see

GP – arranges initial tests to investigate symptoms; assists you with treatment decisions and works in partnership with your specialists in providing ongoing care when cancer is diagnosed

Breast physician – diagnoses breast cancer and other breast conditions, especially when initial test results are unclear; provides care and support during and after treatment

Radiologist – analyses mammograms, ultrasounds and other scans; performs fine needle and core biopsies to confirm diagnosis

Radiographer/sonographer – performs mammograms, breast ultrasound and other scans

Breast surgeon – diagnoses breast cancer, performs surgical (excisional) biopsies in some clinics; performs breast surgery; some breast surgeons also perform breast reconstruction;

oncoplastic breast surgeons specialise in using plastic surgery techniques to reconstruct breast tissue after surgery

Reconstructive (plastic) surgeon – performs breast reconstruction after mastectomy

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Breast care nurse – provides breast cancer care; also provides information and facilitates referrals during and after treatment

Chemotherapy nurse – administers drugs and provides care, information and support throughout treatment

Anaesthetist – assesses your health before the operation, administers anaesthetic and looks after you during and after surgery; plans your pain relief

Radiation therapist – plans and delivers radiation therapy

Physiotherapist, Exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve fitness and wellbeing

Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

Lymphoedema practitioner – educates people about lymphoedema prevention and management, and provides treatment if lymphoedema occurs; is often a physiotherapist or occupational therapist

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Psychologist, Counsellor – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Genetic counsellor – provides advice for people with a strong family history of breast cancer or for people with a genetic condition linked to cancer

Sexual health counsellor – helps you manage the sexual side effects of cancer and its treatments

How is breast cancer diagnosed?

If you notice any breast changes or a swelling in your armpit, your GP will ask about your medical history and any family history of breast cancer.

They will do a physical examination, checking both breasts and the lymph nodes in your armpit and above your collarbone. Your GP may also arrange some imaging tests, such as a diagnostic mammogram and/or an ultrasound and, if required, a biopsy. This is called a triple test.

Sometimes, a specialist will arrange these and additional tests, such as a breast MRI scan. You will also be referred for further tests if a screening mammogram has shown anything unusual.

Mammogram

A mammogram is a low-dose x-ray of the breast tissue. It can check any lump or other breast changes found during a physical examination. It can also show changes that are small or cannot be felt during a physical examination. If you have breast implants, it is important to let staff know before the mammogram.

Your breast is placed between 2 x-ray plates. The plates press together firmly to spread out the breast tissue so that clear pictures can be taken. You will feel some pressure, which can be uncomfortable, but the mammogram only takes 10–15 seconds. Both breasts will be checked.

Tomosynthesis – Also known as three-dimensional mammography, tomosynthesis takes x-rays of the breast from many angles and combines them into a three-dimensional (3D) image. This may be better for finding small breast cancers, particularly in dense breast tissue.

Contrast enhanced mammogram (CEM) – This combines tomosynthesis with a dye (contrast) that is injected into a vein in your arm. A CEM may be helpful for people with dense breast tissue.

A national screening program provides a free mammogram for all women aged over 40. For more information, call 13 20 50 or visit BreastScreen Australia.

Before a scan, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. Also tell them if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound uses soundwaves to create a picture of breast tissue. It does not use radiation. It is often the first test done in women under 30 years with breast changes, or if a screening mammogram has picked up breast changes, or if you or your GP can feel a lump.

A gel will be spread on your breast, and then a small device (transducer) is moved over the breast and armpit. This sends soundwaves that echo when they meet something dense, like a tumour. A computer creates a picture from these echoes. The scan takes 15–20 minutes and is painless.

Breast MRI scan

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan uses a large magnet and radio waves to take pictures of the breast tissue. It does not use radiation. It is mainly used for people at high risk of breast cancer or who have very dense breast tissue or breast implants. It may also be used if other imaging test results are unclear or to help plan surgery.

Before a breast MRI scan, you will usually have an injection of a dye (called contrast) to help show any abnormal breast tissue. You will lie face down on a table, which will slide into a large, cylinder-shaped machine. The scan can take up to 40 minutes. It is painless but loud, so you will wear earplugs. Some people feel claustrophobic. If you are concerned, talk to your doctor. You may be offered a mild sedative.

Before a scan, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. Also tell them if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Biopsy

If breast cancer is suspected, a small sample of cells or tissue is taken from the lump or area of concern. A specialist doctor called a pathologist then checks the sample under a microscope for any cancer cells.

There are different ways of taking a biopsy and you may need more than one type. The biopsy may be done in a specialist’s rooms, at a radiology practice, in hospital or at a breast clinic. After any type of biopsy, your breast may feel sore and be bruised for a few days.

- Fine needle aspiration (FNA) – A thin needle is inserted into an abnormal lymph node or other tissue, often with an ultrasound to help guide the needle into place. Tiny pieces of tissue can then be sucked out through the needle. A local anaesthetic may be used to numb the area.

- Core biopsy – Several pieces of tissue are removed with a needle. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the area, and a mammogram, ultrasound or MRI scan is used to guide the needle into the right area.

- Vacuum-assisted core biopsy – A needle attached to a suction-type instrument is inserted into the breast through a small cut in the skin. A larger amount of tissue is removed with a vacuum biopsy, making it more accurate in some cases. The needle is usually guided into place with a mammogram, ultrasound or MRI. A local anaesthetic is used, but you may feel some discomfort. Stitches are not usually needed.

- Surgical (excision) biopsy – If a needle biopsy is not possible, or the diagnosis remains unclear, you may have a surgical biopsy to remove all or part of a lump. A wire or small surgical clip may be inserted to act as a guide during the surgery. The tissue is then removed under general anaesthetic. This is usually done as day surgery.

Further tests

If the tests show that you have breast cancer, you may have further tests to check whether the cancer has spread to other parts of your body. You will have a blood test to check your general health, and in some cases, it will test for specific tumour markers. You may also have some of the following types of scans.

Bone scan – A bone scan is used to see if the breast cancer has spread to your bones. A small amount of radioactive solution is injected into a vein, usually in your arm. This solution is attracted to abnormal areas of the bone. After a few hours, the bones are viewed with a scanning machine. The scan is painless and the solution is not harmful.

CT scan – A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-ray beams to take pictures of the inside of the body. Before the scan, dye (contrast) will be injected into a vein in your arm. This dye helps to make the pictures clearer. For the scan, you lie flat on a table while the scanner takes pictures. The scan takes about 30 minutes and is painless.

PET scan – In a PET (positron emission tomography) scan, a small amount of low-level radioactive solution is injected into a vein in the arm or hand. Any cancerous areas take up more of the radioactive solution and may show up brighter in the scan.

Before a scan, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or had a reaction to dyes during previous scans. Also tell them if you have diabetes or kidney disease or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Tests on breast tissue

If tests on the biopsy sample confirm you have breast cancer, extra tests on the biopsy sample will be done to understand more about the breast cancer and help plan treatment. The results will be included in the pathology report.

Hormone receptor status – ER+ and/or PR+ (70-80% of all breast cancers)

The hormones oestrogen and progesterone are produced naturally in the body. A receptor is a protein on the surface of the cell. Normal breast cells have oestrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR). Breast cancers that have these receptors are known as ER positive (ER+) or PR positive (PR+). This means that oestrogen or progesterone enters the cell, where it may stimulate cancer cells to grow.

ER+ and PR+ cancers are usually treated with hormone therapy drugs (also known as endocrine therapy) that block the receptor, or drugs that reduce the amount of hormones that the body makes (aromatase inhibitors).

If the cancer has low levels of oestrogen receptors, hormone therapy drugs are sometimes used. These drugs are not used for cancers with no oestrogen receptors.

HER2 status – HER2+ (15-20% of all breast cancers)

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein that is found on the surface of some cells and controls how cells grow and divide. HER2 levels are worked out with an initial test of the protein, and then can be confirmed with an in-situ hybridisation (ISH) test, which is done before giving targeted therapy.

Tumours with high levels of these receptors are called HER2 positive (HER2+). Tumours with low levels are called HER2 negative (HER2– or HER2 low).

It is often recommended that people with HER2+ breast cancer have chemotherapy and targeted therapy before they have surgery (neoadjuvant treatment). Depending on how the cancer responds to the neoadjuvant treatment and surgery, you may also have chemotherapy or targeted therapy after surgery (adjuvant treatment),

Triple negative breast cancer – ER–, PR– and HER2– (10-20% of all breast cancers)

Some breast cancers do not have oestrogen (ER–), progesterone (PR–) or HER2 (HER2–) receptors. These are called triple negative breast cancers.

Triple negative breast cancers do not respond to hormone therapy or to the targeted therapy drugs used for HER2+ cancers in early breast cancers.

These types of cancer usually respond well to chemotherapy, so this may be used before and/or after surgery (neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatment).

Some other types of targeted therapy may be used for triple negative breast cancer. Recently, various types of immunotherapy have been shown to work well for some triple negative cancers. These may be used before surgery for larger cancers or for cancers that also affect lymph nodes.

What are gene expression profile tests?

Gene expression profile tests may be done on the biopsy sample. These tests look at which genes are active in the cancer cells. The results provide information about the risk of cancer returning.

These tests may also be called genomic tests or molecular assays. They are different to genetic tests, which are used to look for inherited gene faults.

The gene expression profile tests available in Australia are Oncotype DX, EndoPredict, PAM50, and MammaPrint.

The test results will help the doctor work out if chemotherapy will be helpful after surgery. It can take 14 days for the results to come back, so it’s important to order these tests as soon as possible. It may be helpful for your surgeon to order these tests before you see your oncologist.

Ask your doctor if a gene expression profile test is an option for you. The standard pathology tests done on all breast cancers may be all that is needed for your treatment plan. Gene expression profile tests may not be covered by Medicare; check what you may have to pay.

Staging breast cancer

The tests described above show the size of the breast cancer and if it has spread to other parts of the body. This is called staging. It helps you and your health care team decide what treatment is best.

The most common staging system used for breast cancer is the TNM system. Letters and numbers describe how big the tumour is (T), if cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), or if it has spread to the bones or other organs, which is known as having metastasised (M).

The staging system also describes other details about the breast tumour such as oestrogen and progesterone receptor status, HER2 status and the grade of the cancer. Staging is usually done after surgery so the treatment team have full information about the cancer and whether it has spread to lymph nodes. The cancer may be classified as:

- Early breast cancer (stage 1 or 2) – The cancer is contained in the breast and may or may not have spread to lymph nodes in the armpit.

- Locally advanced breast cancer (stage 3) – The cancer is larger than 5 cm, has spread to tissues around the breast such as the skin or muscle or ribs, or has spread to a large number of lymph nodes.

- Metastatic breast cancer (stage 4) – The cancer has spread to other parts of the body from the breast. Also called secondary or advanced breast cancer, it is different from locally advanced breast cancer.

Grading breast cancer

The grade describes how active the cancer cells are and how fast the cancer is likely to be growing.

grade 1 (low grade) – Cancer cells look a little different from normal cells. They are usually growing slowly.

grade 2 (intermediate grade) – Cancer cells do not look like normal cells. They are growing faster than grade 1 cancer cells.

grade 3 (high grade) – Cancer cells look very different from normal cells. They are usually growing fast.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider the stage and grade of the cancer, as well as features such as the cancer’s hormone receptor and HER2 status.

The survival rates for people with breast cancer have increased significantly over time due to more people taking part in breast screening, better tests and scans, and improved medicines and treatments. Doctors often use 5-year survival rates as a way to discuss prognosis. This is because research studies often follow people for 5 years; it does not mean you will survive for only 5 years. It also does not mean that the cancer cannot come back after 5 years.

Compared with other cancers, breast cancer has one of the highest 5-year survival rates when diagnosed early.

Treatment for breast cancer

Treatment for early or locally advanced breast cancer varies from person to person.

The treatment that is best for you will depend on your test results, where the cancer is in the breast, the stage and grade of the cancer, and whether the cancer is hormone receptor and/or HER2 positive or triple negative. Your doctor will also consider your age and general health, and your preferences.

Treatment for early and locally advanced breast cancer usually includes surgery. Before surgery, however, you may have other types of treatment to shrink the cancer. This is called neoadjuvant treatment.

Treatment before surgery

While surgery is often the main treatment for both early and locally advanced breast cancer, you may have other treatments before surgery.

Called neoadjuvant treatment, it may be discussed at an MDT. Chemotherapy is often used before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy or NAC). Or, you may have hormone therapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy, or a combination of these treatments.

Neoadjuvant treatment can help to reduce the size of the cancer before surgery and improve your chance of having a good outcome. It may also mean you can have less complex surgery.

For locally advanced breast cancer, for example, neoadjuvant treatment may mean you can choose to have breast-conserving surgery rather than a mastectomy.

In some cases – particularly for people with HER2+ or triple negative cancers – neoadjuvant treatment can kill all cancer cells. Called a complete pathological response, it improves the chance of a good outcome.

Ask your doctor if neoadjuvant treatment is an option for you. People with early breast cancer may find the Neoadjuvant Patient Decision Aid helpful.

After surgery, you may have radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy. This is called adjuvant treatment. It helps to destroy any cancer cells that remain after surgery.

Surgery

The type of surgery your doctor suggests will depend on the type and stage of the cancer, where it is in the breast, the size of your breast, and what you prefer. In most cases, you will have one or more lymph nodes removed from the armpit (called axillary surgery). Some people also choose to have a new breast shape made during the operation (breast reconstruction).

The 2 different types of surgery used for breast cancer are:

- breast-conserving surgery – when only part of the breast is removed

- mastectomy – when the whole breast is removed.

Depending on your situation, you may have a choice between the 2 types of surgery. Research has shown that for most early breast cancers, having breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy works just as well as a mastectomy.

The operations have different benefits, risks and side effects. Talk to your doctor about the best option for you.

Breast-conserving surgery

Removing only part of the breast is called breast-conserving surgery. It is also known as a lumpectomy or wide local excision.

The surgeon removes the tumour and some of the healthy tissue around it, so that you can keep as much of your breast as possible. The operation will leave a scar, and it may change the size and shape of the breast and the position of the nipple.

Pathology tests on breast tissue

A pathologist looks at the removed tissue under a microscope to check for an area of healthy cells around the cancer (called a clear margin).

The pathologist will also give information about:

- the size and grade of the cancer

- whether the cells are hormone receptor positive and/or HER2+ or triple negative

- whether the cancer has spread to any lymph nodes.

If your removed tissue shows multiple cancers, each cancer will be tested separately. The pathology report will help your doctors work out what other treatment may be best for you. If there are cancer cells found close at the edge of the tissue (which is called an involved or positive margin), there is a higher risk of the cancer returning.

You may need to have further surgery to remove more tissue (called a re-excision or wider excision). Your doctor may also suggest that you have a mastectomy.

Mastectomy

Surgery to remove the whole breast is called a mastectomy. One breast may be removed (single or unilateral mastectomy) or both breasts (double or bilateral mastectomy). A mastectomy may be recommended if:

- there is cancer in more than one area of the breast

- the cancer is large compared with the size of the breast

- it is difficult to get a clear margin around the tumour

- you have inflammatory breast cancer

- you have had radiation therapy to the same breast before and so cannot have it again

- the cancer has come back or you have a new cancer in the same breast

- you have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.

You may prefer to have a mastectomy instead of breast-conserving surgery – even if you have a very small cancer. You will not usually have radiation therapy after a mastectomy, although it may be offered in some situations.

The nipple is often removed in a mastectomy. In some cases, however, the surgeon may perform a skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy. This means that more of the normal skin (with or without the nipple) is kept. If you have decided to have a reconstruction, and can have a skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, the reconstruction is sometimes done at the same time.

If you don’t have a reconstruction, you have the option of wearing a soft breast form with a specially designed bra while your surgical wound heals. Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) provides a free bra and temporary soft form. Speak to your breast care nurse for more details. Cancer Council SA can also provide a soft temporary prosthesis, call 13 11 20 for more information. After the wound has healed and the area is comfortable, you have the option to be fitted for a permanent breast prosthesis.

What about the other breast?

If you need a mastectomy because of cancer in one breast, you may think it’s safer to have the other breast removed as well. For most people, the risk of getting cancer in the other breast is low.

If you have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene or another rare breast cancer gene mutation, this does increase the risk of developing another breast cancer, so you may choose to have a double mastectomy (bilateral mastectomy) to remove both breasts.

Whether to have a double mastectomy is a complex decision. It is best to talk with your treatment team about the risks and benefits before making a final decision.

Breast reconstruction

Breast reconstruction is surgery to make a new breast shape (also called a breast mound). There are different ways to construct a breast shape. It can be done using:

- implants

- a flap of your own skin, fat or muscle (an autologous reconstruction)

- a breast implant and your own tissue.

A breast reconstruction can be done at the same time as a mastectomy (immediate reconstruction); or you may prefer to wait for several months or years before having a reconstruction (delayed reconstruction). If you are not having an immediate reconstruction but might consider it in the future, discuss this with your surgeon before surgery. This will help them to plan the mastectomy.

Some people decide not to have a reconstruction and prefer to “go flat”, while others choose to wear a breast prosthesis.

Removing lymph nodes

Cancer cells that spread from the breast usually first spread to the axillary lymph nodes, which are in and around the armpit. Removing some or all of these lymph nodes helps your doctor to check for any cancer spread. The operation to remove lymph nodes is called axillary surgery. It is usually done during breast surgery but may be done in a separate operation. There are 2 main types of axillary surgery.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) – When breast cancer spreads outside the breast, it first goes to a particular lymph node or nodes in the armpit or near the breastbone (sternum). These are called the sentinel nodes. A sentinel node biopsy finds and removes them so they can be tested for cancer cells.

If there are no cancer cells in the sentinel nodes, no more lymph nodes are removed. If there is more than a small amount of disease in the sentinel nodes, you may have axillary lymph node dissection or radiation therapy.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) – If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, then most or all of the axillary lymph nodes (usually 10–25) may be removed to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back (recurrence) in the armpit. The nodes are tested and the results guide what other treatment may be needed. ALND is also called axillary lymph node clearance (AC). Radiation therapy may be used instead of ALND.

Side effects – You may have arm or shoulder stiffness, weakness and pain; numbness in the arm, shoulder, armpit and parts of the chest; fluid collecting near the surgical scar (seroma); lymphoedema; and cording. Side effects are usually worse after ALND than after an SLNB because more lymph nodes are removed in an ALND.

Finding the sentinel nodes

To work out which lymph nodes are sentinel nodes, one or a combination of these procedures is used:

1) Lymphatic mapping

A small amount of a harmless radioactive solution is injected into the skin over the breast cancer tumour.

A CT scan is then taken to show which lymph nodes the radioactive solution flows to first. These are most likely to be the sentinel nodes.

Lymphatic mapping is done either the day before or on the day of the surgery.

2) Dye injection (not always used)

If dye is being used, it will be injected into the breast. The dye, which may be blue or green, moves into the lymphatic vessels and stains the sentinel nodes first. This is done under general anaesthetic during the surgery.

Because of the dye, you may notice blue-green urine (wee) and bowel movements (poo) when you go to the toilet the next day. You may also have a blue patch on the breast for weeks or longer. Your skin may look a bit grey but will fade once the dye washes out in your urine.

3) Handheld probe

As well as looking at where the dye travels to first (if used), the surgeon uses a small handheld device called a probe during the surgery to detect the radioactive solution injected during the lymphatic mapping.

This helps to check that the sentinel nodes have been located and the surgeon can then remove them for testing.

What to expect after surgery

If you have any questions about your recovery and how best to look after yourself when you get home, ask the doctors and nurses caring for you. If you are referred to a breast care nurse, they can give you information about what to expect after surgery and provide support.

Your hospital stay will depend on the surgery you have and how well you recover.

- breast-conserving surgery – you usually go home the same day, or may stay overnight

- mastectomy – you usually stay in hospital for 1-2 nights

- reconstruction after mastectomy – you usually stay in hospital for several days.

Managing dressings and tubes – A dressing will cover the wound to keep it clean. This may be changed while you are in hospital but is usually removed after about a week. You may have one or more drainage tubes to drain fluid from the surgical site into a bottle. These can stay in place for up to one week, or occasionally 2 weeks. Nurses will show you how to look after the wound and drainage tubes at home, or a community nurse, GP or your surgeon may help you. If you notice redness or discharge around the surgical area or develop a fever over 38°C, let your treatment team know immediately.

Recovery time – The time it takes to recover from surgery will depend on the type of surgery you have had and your health. You may feel better after a few days, or it may take several weeks or longer if you have had a mastectomy with a reconstruction.

Avoid heavy lifting – Do not do vigorous physical activity or heavy lifting in the initial weeks after surgery. Your treatment team will let you know when you can resume normal activities. You may be given some gentle exercises to reduce the risk of shoulder stiffness.

Shower carefully – Keep the wound clean, and gently pat it dry after showering. Avoid baths.

Manage pain – While in hospital, you will have pain relief through a drip (intravenous or IV), an injection or as tablets. You will also be given pain medicine when you go home. You are likely to need stronger pain relief after an ALND or a mastectomy than after breast-conserving surgery.

Prevent blood clots – While in bed, you should try to do some deep breathing exercises, and move your legs around to help prevent blood clots in the deep veins of your legs (deep vein thrombosis or DVT). As soon as you are able, you will be asked to get up and walk around. You may wear elastic (compression) stockings or use other devices to help prevent clots. Your doctor

might prescribe medicine that reduces the risk of blood clots forming.

Apply moisturiser – Gently massage the area with moisturiser once any stitches or adhesive strips are removed and the wound has completely healed. About 6 weeks after surgery, your surgeon may suggest that you use silicone gels and sheets to reduce scarring.

Avoid cuts – Your treatment team may advise you to wait until the wound has completely healed if you want to shave or wax your armpits.

What your breast looks like after surgery

How your breast will look after surgery depends on the type of surgery that you have, as well as the size of your breast and your body shape. It can take up to a few weeks for any bruising and swelling of the surgery area to go away.

After breast-conserving surgery – The size and position of the scar will depend on how much tissue was removed. The scar will usually be less than 10 cm and near where the cancer was or around the areola or near the breast fold. But this can vary depending on your breast size and how much breast tissue needs to be removed. It can also change if you need to have further surgery to remove more tissue. If a larger area needs to be removed, surgical techniques known as oncoplastic surgery can reshape the breast after breast-conserving surgery.

After a mastectomy – The scar will be across the skin of the chest. If you have surgery to remove the lymph nodes, the scar will also be in the armpit. At first the scar will be firm, slightly raised and red. Over the next few months, it will flatten and fade.

Impact on self-esteem

Scars or changes to how your breast looks can affect how you feel about yourself (self-image and self-esteem). If you have had a mastectomy (or part of your breast removed), it’s common to feel a sense of loss. It may also affect your sense of identity.

Seeking support – Talking to someone who has had breast cancer surgery can be helpful. Cancer Council’s Cancer Connect program may be able to link you to others who’ve had a similar experience. Speaking with a counsellor or psychologist for emotional support and coping strategies can also help. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for details.

Side effects of surgery

Some common side effects are discussed below. Talk to your treatment team about the best ways to deal with them.

Fatigue – Cancer treatment and the emotional impact of the diagnosis can be tiring. Fatigue is common and may continue for weeks or months. Research shows that exercise during and after cancer treatment is safe and can help improve fatigue. You can also ask your GP if you are eligible for some Medicare-funded sessions with and exercise physiologist or physiotherapist.

Download our fact sheet ‘Fatigue and Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Exercise for People Living with Cancer’

Shoulder stiffness – Arm and shoulder pain, weakness, stiffness and reduced movement are common after surgery and after radiation therapy. Ask your treatment team when you can start exercising your arm. A physiotherapist or exercise physiologist can show you exercises to reduce shoulder stiffness or pain. This may help prevent lymphoedema.

Download our poster ‘Arm & shoulder exercises after surgery’

Numbness and tingling – Surgery can bruise or injure nerves. You may feel numbness and tingling in the armpit, upper arm or chest area. You may also notice a loss of feeling in your breast or nipple. These changes often improve within a few weeks but may take longer. Sometimes the numbness or tingling may not go away completely. A physiotherapist or occupational therapist can give you exercises that may help.

Seroma – Fluid may collect in or around the surgical scar and cause a balloon-like swelling. This is most common after a mastectomy. A seroma can also develop in the armpit after an ALND. The build-up of fluid can be uncomfortable but is not harmful. Some breast care nurses, your specialist or GP, or a radiologist can drain the fluid using a fine needle and a syringe. This procedure is not painful, but it may need to be repeated over a few appointments.

Lymphoedema – Fluid building up in the tissue of the arm or breast may cause swelling after any lymph node surgery. It is common to have some swelling of your arm or breast after surgery, but this usually settles in the weeks afterwards. If this swelling builds up over weeks or months, this usually means you have lymphoedema. It can happen any time, even years after surgery (or radiation therapy) to the lymph nodes.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Lymphoedema’

Post-mastectomy pain – It is rare to have prolonged pain after a mastectomy but you may find the scar uncomfortable for some time. If pain or discomfort is ongoing, let your treatment team know.

Cording – Also known as axillary web syndrome, cording is caused by hardened lymph vessels. It feels like a tight cord running from your armpit down the inner arm, sometimes to the palm of your hand.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy uses a controlled dose of radiation to kill cancer cells or damage them so they cannot grow, multiply or spread. The radiation is usually in the form of x-ray beams. It does not cause you to become radioactive during the period of treatment.

Radiation therapy may be recommended:

- after breast-conserving surgery – usually a part of standard treatment

- after a mastectomy – you may have radiation to the chest wall and lymph nodes above the collarbone, and sometimes lymph nodes next to the breastbone

- if the sentinel node has cancer cells – you may have radiation to the armpit instead of ALND

- after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and before surgery

- after adjuvant chemotherapy.

You will usually start radiation therapy within 8 weeks of surgery. If you’re having chemotherapy after surgery, radiation therapy will begin about 3–4 weeks after chemotherapy has finished.

Planning radiation therapy

Treatment is carefully planned to cause the most harm to the cancer cells and to limit damage to the surrounding healthy tissues. Planning involves several steps, which may occur over a few visits.

You will have a planning session at the radiation therapy centre. During this appointment, you will have a planning CT scan of the area to be treated. Sometimes marks are put on your skin so the radiation therapists can ensure you are lined up correctly each time you are treated. These marks are usually small dots (tattoos), and they may be temporary or permanent. Talk to your radiation therapists if you are worried about these tattoos. Invisible tattoos are available in some centres. If you have had breast-conserving surgery, the surgeon can sometimes place tiny markers (called fiducial markers) in your breast tissue to show where the cancer used to be. This helps the radiation oncology team to deliver the radiation therapy more precisely.

You may be asked to try a deep inspiration breath hold (DIBH) technique. This involves taking and holding a deep breath for 20–30 seconds during treatment. DIBH helps to inflate the lungs and move the heart away from the radiation field, reducing the risk of heart damage.

Having radiation therapy

You will probably have radiation therapy daily from Monday to Friday for 1–6 weeks. Most people have radiation therapy as an outpatient and go to the treatment centre each day.

Each radiation therapy session will be in a treatment room. Setting up the machine can take 10–30 minutes, but the actual treatment takes only 1–5 minutes. You will lie on a table under the machine and your breast will be exposed. The radiation therapist will leave the room and then switch on the machine, but you can talk to them through an intercom.

Radiation therapy is not painful, but you will need to lie still while it is given. Most people will be lying on their back with their arms up. If DIBH is recommended for you, the radiation beam will only be turned on when you are in the DIBH position.

If you are having radiation therapy at a private centre, Medicare will cover some of the cost, but your private health insurance may not, so you may have to pay some of the cost yourself (out-of-pocket costs). If you are worried about the cost, speak to your treatment team about having treatment in a public hospital.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may cause the following side effects:

Skin problems – You may have some redness around the treated area. The skin may become dry and itchy, blister, or become moist and weepy. It usually returns to normal 4–6 weeks after radiation therapy ends. Sometimes skin can become very irritated or peel (radiation dermatitis). You may need dressings, or special creams or gels, to help the area heal.

Tiredness – You may start to feel tired 1–2 weeks after radiation therapy begins. Fatigue usually gets better a few weeks after treatment finishes.

Aches – You may feel minor aches or shooting pain in the breast area during or after radiation therapy. It should ease over time.

Swelling – Some people have swelling or fluid build-up in the breast (breast oedema or lymphoedema) that can last for up to a year or longer. Radiation therapy to the armpit increases the risk of swelling in the arm (lymphoedema).

Hair loss – Radiation therapy to the breast won’t make you lose the hair on your head, but you will usually lose hair from the treated armpit.

Other side effects – Late effects can develop months or years after radiation therapy. Part of the lung behind the treatment area may become inflamed, causing a dry cough or shortness of breath. There is a slight risk of heart problems, but this usually happens only if you have treatment to your left breast or if you smoke. Hardening of tissues (fibrosis) may happen months or years after treatment. In rare cases, radiation therapy may cause a second cancer.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth. It may be used before or after surgery. It is often used for breast cancers that are not sensitive to hormone therapy, are HER2+ or triple negative, or for inflammatory breast cancers. Chemotherapy is sometimes used for hormone receptor positive breast cancers.

Having chemotherapy

Different types of chemotherapy drugs are used. The choice of drugs will depend on the type of cancer, how far it has spread and what other treatments you are having. Usually, you will have a combination of drugs. Common drugs include carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, doxorubicin, epirubicin and paclitaxel. Your treatment team may also refer to the drugs by their brand names, or letters like AC or TC. Your medical oncologist will talk to you about the most suitable types of chemotherapy drugs, as well as their risks and side effects. For more information, visit eviQ.

Generally, chemotherapy is given through a vein (intravenously). You will usually be treated as an outpatient, but occasionally you may have to stay in hospital overnight. Chemotherapy is usually given once every 1–3 weeks for 3–6 months.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy damages cells as they divide. This makes the drugs effective against cancer cells, which divide rapidly. However, some normal cells – such as hair follicles, blood cells and cells inside the mouth or bowel – also divide rapidly. Side effects happen when chemotherapy damages these normal cells. Unlike cancer cells, normal cells can recover, so most side effects are temporary.

Nausea – You may feel sick for a few hours or days after each treatment. Not everyone feels sick, and you’ll be given medicine to help prevent it. Some medicines may cause constipation; talk to your doctor about this.

Diarrhoea – You may have loose, watery stools and feel like you urgently need to go to the toilet. You may be given medicine to manage diarrhoea.

Hair loss – You may lose the hair from your head and other areas of the body (e.g. eyebrows, underarms and pubic area). Cold caps may prevent hair loss on your head in some cases.

Swelling (oedema) – Some medicines used with chemotherapy drugs can cause excess fluid (fluid retention) to build up in the body. This can affect the arms and the trunk, but it usually gets better when treatment ends.

Changes to fertility – Chemotherapy can cause infertility in females and males. If you may want to have children in the future, it’s essential that you talk to your cancer specialists about your options and ask for a referral to a fertility specialist before treatment starts.

Heart problems – The risk is small but chemotherapy can sometimes damage the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy). Your heart health will be checked before, during and after treatment. If you are at risk of heart damage, you may be offered other types of drugs.

Peripheral neuropathy – You might develop tingling in your hands or feet. This is called peripheral neuropathy.

Other side effects – These include an increased infection risk, fatigue, mouth ulcers, constipation, and memory changes.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy, also called endocrine therapy or hormone-blocking therapy, slows or stops the effect of oestrogen. It is used to treat breast cancer that is hormone receptor positive. Hormone therapy is often used to lower the risk of the cancer coming back. It may also be used to reduce the risk of certain conditions, including LCIS and some DCIS, developing into invasive breast cancer.

There are different types of hormone therapy. The type used will depend on your age, type of breast cancer and if you have reached menopause.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen can be used at any age, whether you have been through menopause or not. You need to take a daily tablet for 5–10 years.

Side effects – In females, tamoxifen can cause menopausal symptoms, although it doesn’t bring on menopause. It may also cause changes in thinking and memory, and vaginal discharge. There is a very small risk of developing cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer), particularly if you have gone through menopause. Always let your treatment team know if you have any unusual vaginal bleeding. In males, side effects can include low sex drive (libido) and erection problems.

Tamoxifen increases the risk of blood clots. See a doctor immediately if you have swelling, soreness or warmth in an arm or leg, or a sudden shortness of breath or chest pain.

You are unlikely to have all of these side effects, and they usually improve with time. Your doctor and breast care nurse can help you to manage side effects. Tell your doctor if you take an antidepressant. Some types of antidepressant drugs may affect how well tamoxifen works.

Aromatase inhibitors

After menopause, the ovaries stop making oestrogen. However, both females and males make small amounts of oestrogen in body fat and the adrenal glands. Taking aromatase inhibitors will help reduce how much oestrogen is made in the body. This is important because oestrogen can cause some cancers to grow.

Aromatase inhibitors (e.g. anastrozole, exemestane and letrozole) are mostly used if you have been through menopause, have had your ovaries removed, or are male. They may be used if you have not been through menopause but have a high risk of the cancer returning. You may also be given a drug to stop the production of oestrogen (e.g. goserelin). This can be started before or after chemotherapy but must be continued while you take the aromatase inhibitor.

Side effects – Aromatase inhibitors can cause menopausal symptoms such as vaginal dryness and low mood. These drugs may also cause itchiness, joint pain, and weakening of the bones (osteoporosis). Your bone health will be monitored during treatment and you may be prescribed a drug to protect your bones. Consider seeing a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist for an exercise plan. If you have arthritis, aromatase inhibitors may worsen joint stiffness and pain. Exercise or medicines from your doctor may help. Your doctor may also suggest changing to one of the other types of aromatase inhibitor.

Ovarian suppression

If you have not been through menopause, drugs or surgery can stop the ovaries from producing oestrogen. This is called ovarian suppression. It may also be recommended as an additional treatment for people taking tamoxifen or for premenopausal women taking an aromatase inhibitor instead of tamoxifen.

Temporary ovarian suppression – The drug goserelin stops oestrogen being made. It is given as an injection into the abdomen (belly) once a month for 2–5 years to bring on temporary menopause. Side effects are similar to those of permanent menopause. The drug may also help protect the ovaries during chemotherapy, so it is often given to women who want to preserve their fertility.

Permanent ovarian treatment – Ovarian ablation is rarely needed, but this procedure permanently stops the ovaries from producing oestrogen. It usually involves surgery to remove the ovaries (oophorectomy). Sometimes radiation therapy is used.

Ovarian ablation will bring on permanent menopause. This means you will no longer be able to fall pregnant naturally.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy drugs attack specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Different types of targeted therapy drugs are used for different types of breast cancer.

HER2-targeted agents

For early or locally advanced HER2+ breast cancer, the most common targeted therapy drug used is trastuzumab. Your treatment team may refer to trastuzumab by a brand name (e.g. Herzuma, Kanjinti or Ogivri). It is also known as Herceptin, although this version is now rarely used in Australia.

Trastuzumab works by attaching itself to HER2+ breast cancer cells, destroying the cells or reducing their ability to divide and grow. It also encourages the body’s own immune cells to help find and destroy cancer cells. Usually used in combination with chemotherapy drugs for early breast cancer, trastuzumab can increase the effect of the chemotherapy.

Trastuzumab can be given through a drip into a vein (infusion) or as an injection under the skin. The first infusion takes about 90 minutes (called the loading dose). The following infusions each take 30–60 minutes. You will usually have a dose every 3 weeks, for up to 12 months. The first 4–6 doses are given while you are having chemotherapy treatment.

Side effects – Side effects are usually caused by the chemotherapy drugs, and often ease once chemotherapy finishes and you are having trastuzumab only. Side effects from trastuzumab are uncommon, but can include headache, fever and diarrhoea. In some cases, trastuzumab can affect how the heart works, so you will have tests to check your heart function before and during treatment.

Several new drugs have been developed to treat HER2+ breast cancer with or after trastuzumab. These include: pertuzumab, which is given before surgery (neoadjuvant); and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), which is given after surgery (adjuvant). Your doctor will let you know if these drugs are appropriate for you.

CDK inhibitors

Abemaciclib is a type of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor. It is used with hormone therapy. Abemaciclib may be used after surgery and chemotherapy for larger, high-risk ER+, HER2– breast cancers, for cancers involving several lymph nodes, or cancers at high risk of returning. Another drug (ribociclib) may soon become more widely available.

Side effects – Nausea or diarrhoea may occur, but this can be managed. Your blood count may be affected, so regular blood tests are needed.

PARP inhibitors

There are several new drugs for people who have inherited a BRCA mutation, or whose cancer has developed BRCA mutations. These are called poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and include the drug olaparib. Ask your doctor if this may be suitable for you.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. A drug called pembrolizumab may be used for people with certain types of triple negative breast cancer. Pembrolizumab is used together with a chemotherapy drug. Pembrolizumab is given through a vein (intravenously), and treatments usually take about 30 minutes.

Side effects – These may be caused by the immunotherapy, the chemotherapy or both. Common side effects include a rash, fatigue, diarrhoea (which can be severe), breathlessness, joint pains, diabetes, nerve problems, muscle weakness and dry eyes. It can cause inflammation in other organs, including the thyroid, pituitary gland, liver, kidneys and pancreas. It can also affect the adrenal gland, which can lead to low levels of certain hormones (e.g. cortisol). If you notice these or any other side effects, it’s important to let your treatment team know – some side effects can be life-threatening if left untreated.

Most side effects, however, can be managed if they are reported early. Sometimes, immunotherapy may need to be stopped or interrupted. Side effects from immunotherapy can occur for up to 12 months after the last dose was given. Pregnancy should be avoided during this time.

Treatment for advanced breast cancer

Advanced breast cancer is different from locally advanced breast cancer.

Locally advanced breast cancer is cancer (larger than 5 cm) that has spread to tissue around the breast or to a large number of lymph nodes. Advanced breast cancer is cancer that has spread to more distant body parts. It is also called metastatic or secondary breast cancer.

Breast cancer can spread to many different parts of the body, but it is most likely to spread to the bones, liver, lungs or brain.

The treatment for advanced breast cancer varies from person to person. It will depend on the type of breast cancer and where in the body the cancer has spread.

The treatment for advanced breast cancer aims to control the spread of the cancer and relieve any symptoms you may develop. You may have one or more of the following treatments:

In some cases, radiation therapy may be used to reduce the size of the cancer and to relieve pain.

Surgery is not often used for advanced breast cancer, but it may be used to treat cancer in the bones, lungs, brain or liver.

While it’s not possible to cure advanced breast cancer at this time, these treatments may improve quality of life for many months and sometimes years.

For more information related to advanced breast cancer, see our other resources:

- Living with Advanced Cancer

- Understanding Cancer Pain

- Understanding Secondary Bone Cancer

- Understanding Secondary Liver Cancer

- The Thing About Advanced Cancer podcast series.

Breast Cancer Network Australia has more detailed information about advanced breast cancer.

Managing side effects

It will take time to recover from the physical and emotional changes caused by your treatment.

Side effects can vary. Some people will experience just a few side effects, while others will have more.

Feelings of loss and change

It’s common to feel emotional after a cancer diagnosis. You may feel a sense of grief or loss – for your health and wellbeing, your dreams or freedoms, even what you can wear. Grief can feel like waves of sadness or being teary, and usually settles over time. The busyness of cancer treatment may mean you do not feel grief until it is over. If concerned, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to talk to someone about how you are feeling.

Lymphoedema

Lymphoedema is the swelling (oedema) that develops when lymph fluid builds up in the tissues of part of the body, such as an arm or breast. When lymph nodes have been damaged or removed, lymph fluid may not be able to drain properly and builds up in the tissues.

Some breast cancer treatments may cause lymphoedema (e.g. surgery to remove lymph nodes and radiation therapy to the armpit). Many people who are at risk, however, never develop lymphoedema.

Lymphoedema can affect people at any time – during active treatment or months or even years afterwards. Regular screening check-ups may be recommended for some people, so ask your treatment team if this might be an option for you. Signs to look for include the swelling of part of your arm or your whole arm; a feeling of tightness, heaviness or fullness in the fingers, wrist or the arm; and aching in the affected area. These signs may begin gradually or come and go.

Some people experience pain, redness or fever, which can be caused by an infection called cellulitis in the area with lymphoedema. If you have any of these symptoms, see your doctor as soon as possible. Lymphoedema is easier to manage when diagnosed and treated early.

Cording

Cording (axillary web syndrome) can develop weeks or months after any type of breast surgery. Caused by hardened lymph vessels, cording feels like a tight cord running from your armpit down the inside of the arm, sometimes to the palm of your hand. You may see and feel raised cord-like structures across your arm, chest or breast, which may limit how you move. Gentle stretching exercises in the first weeks after surgery can help improve movement. Massage, physiotherapy, or low-level laser treatment by a lymphoedema practitioner may also help reduce pain and tightness. Cording usually improves over a few months.

Nerve pain

Mastectomy, SLNB and ALND can cause nerve pain in the arm or armpit, and mastectomy can cause nerve pain in the chest wall. This may feel like pins and needles, tingling, or stabbing pain. It usually settles within a few weeks. If nerve pain is ongoing, ask your doctor about ways to manage it.

Some chemotherapy drugs can damage nerves in the hands and feet. This is called peripheral neuropathy or chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). It can cause weakness, numbness, pins and needles and, occasionally, burning or shooting pain. These symptoms usually improve over a matter of months, but they can be permanent.

If you have any of these symptoms, tell your health care team. Your doctor will help you manage pain from any permanent nerve damage. A physiotherapist and occupational therapist can help you improve or manage symptoms, and a psychologist or counsellor can teach you coping strategies to manage any ongoing pain.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Peripheral Neuropathy and Cancer’

Hair loss

If you lose your hair during chemotherapy, you may choose to wear a wig, scarf, turban or hat while your hair is growing back. Or you might feel comfortable leaving your head bare. You could try out a few options over time and see what feels like the right thing for you. Generally, hair starts to grow back after your treatment ends.

Some treatment centres offer cold caps (also called scalp cooling), which may prevent total head hair loss, but this depends on the chemotherapy drugs used. Ask your treatment team if cold caps might be an option for you.

The Look Good Feel Better program can help you to manage the appearance-related effects of cancer treatment and boost self-esteem. You can also call them on 1800 650 960.

Thinking and memory changes

Some people with breast cancer notice changes in how they think and remember information. This is called cancer-related cognitive impairment or may be referred to as “chemo brain”, “cancer fog” or “brain fog”. The exact cause is unknown, but studies suggest these changes may be caused by the cancer, emotions such as anxiety and depression, cancer treatment, anaesthetic given for surgery, and side effects such as fatigue, insomnia, pain and hormone changes.

For most people, thinking and memory problems get better within the first year of finishing treatment. Others may have long-term effects. If you have severe or lasting changes to your thinking and memory skills, you can see a clinical psychologist or neuropsychologist for cognitive rehabilitation. Speak to your health care team about the services available at your hospital or from a psychologist.

Listen to our podcast episode ‘Brain Fog and Cancer’

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Changes in Thinking and Memory’

Breast prostheses

A breast prosthesis is a synthetic breast or part of a breast that is worn in a bra or attached to the body with adhesive. It helps give the appearance of a breast shape and can be used after breast surgery.

Temporary prosthesis – In the first month or two after surgery, you may choose to wear a temporary light breast prosthesis called a soft form. This will be more comfortable next to the scar. A free bra and soft form are available through Breast Cancer Network Australia as part of the My Care Kit. To order a kit, speak to your breast care nurse. Cancer Council SA can also provide you with a temporary prosthesis. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

Permanent prosthesis – When you have recovered from treatment, you can be fitted for a permanent breast prosthesis. A permanent breast prosthesis is mostly made from silicone gel and has the shape, feel and weight of a natural breast. It is recommended that you see a trained fitter who can help you choose the right prosthesis. To find a fitter near you, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 or ask your breast care nurse for recommendations.

Changes to body image and sexuality

Breast cancer can affect how you feel about yourself (self-esteem) and make you feel self-conscious. You may feel less confident about who you are and what you can do. These feelings are common; give yourself time to adapt. If you are finding it hard to adjust to changes, ask for support. Most cancer centres have psychologists who may be able to help.

Breast and chest appearance – You may find that having a breast reconstruction or wearing a breast prosthesis improves your self-confidence. Or you may prefer to not have a reconstruction and “go flat”. You may be able to have an areola and nipple tattooed onto the breast after a mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Or you may choose a decorative tattoo to cover scars. For some people, this is a way to take control of their body and express themselves.

Low libido – Breast cancer and its treatment (particularly hormone treatment) can also reduce your desire for sex (libido). You may miss the pleasure you felt from the breast or nipple being stroked or kissed during sex. This may be the case even if you have a reconstruction. If breast stimulation was important for arousal before surgery, you may need to explore other ways of becoming aroused. Some cancer treatment centres have sexual health clinics and other resources that may be able to help.

Vaginal dryness – Some treatments for breast cancer (particularly hormone therapy) can cause vaginal dryness, which can make penetrative sex painful. For most people, sex is more than arousal, intercourse and orgasms. It involves feelings of intimacy and acceptance, as well as being able to give and receive love. Even if some sexual activities may not always be possible, there are many ways to express closeness.

After treatment you should not use any hormone-based contraceptives (“the pill” or hormone implants or injections). It is best to use condoms, diaphragms or intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs).

Download our booklet ‘Sex, Intimacy and Cancer’

Menopause and infertility

Chemotherapy can cause your periods to stop for a short time, or it may cause them to stop permanently (early menopause). Symptoms of menopause include hot flushes, trouble sleeping, vaginal dryness, reduced sex drive (libido), tiredness, dry skin, mood swings, weight gain and osteoporosis. Talk to your doctor or breast care nurse about how to relieve symptoms. If vaginal dryness does not respond to simple measures, talk to your doctor about vaginal oestradiol. Several non-hormonal medicines work well for hot flushes.

If chemotherapy causes menopause, you will not be able to have children naturally. Talk to your doctor before treatment starts, as there may be ways to reduce the risk of early menopause or preserve your fertility.

If you find out you might not be able to get pregnant and have a child, you may feel a great sense of loss. Talking to a counsellor or someone in a similar situation may help. For information about counselling services and support groups in your area, call Cancer Council

13 11 20.

Feelings of loss and change

It’s common to feel emotional after a diagnosis of cancer. You may feel a sense of grief or loss – of your health and wellbeing, your femininity, your dreams or freedoms, even what you can wear. Grief can feel like waves of sadness or being teary, and usually settles over time. The busyness of cancer treatment may mean you don’t feel grief until it’s over. If concerned, call Cancer Council 13 11 20 to talk to someone.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience does not end on the last day of treatment.

Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had breast cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments with your cancer specialist and GP to monitor your ongoing health. This is known as shared care. Your doctors will see how you are going on hormone therapy (if this is part of your ongoing treatment), help you to manage any long-term side effects such as lymphoedema, peripheral neuropathy or heart issues, and check that the cancer has not come back or spread.

During these check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination. You will also be able to discuss how you’re feeling and mention any concerns you may have.

Check-ups after breast cancer treatment are likely to happen every 3–6 months for 2 years. They will become less frequent after that if you have no further problems.

You are likely to have a mammogram and, if needed, an ultrasound every year. You won’t need a mammogram if you’ve had a double mastectomy. If there is a concern the cancer may have come back, you may have a bone scan and a CT, PET or MRI scan. After 5 years with no sign of cancer, women aged 40 and over can continue to have a free mammogram through the national breast cancer screening program.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people find that they think more about the cancer and may feel anxious (“scanxiety”). Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if the cancer returns?

Sometimes, breast cancer does come back after treatment, which is called a recurrence. This is why regular check-ups are important. In most cases, early breast cancer will not come back (recur) after treatment. Although the risk is higher with locally advanced breast cancer, many people will not experience a recurrence.

There are some things that increase the risk that cancer may come back. These include if the cancer was large or the grade was high when first diagnosed, if it was found in the lymph nodes, or if the surgical margin was not clear. Your risk may also be increased if the cancer was hormone receptor negative or if adjuvant treatment (e.g. radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy) was recommended after surgery but was not started or completed. This does not mean the cancer will definitely come back or spread.

Regularly looking at and feeling your breasts to know what is normal (being “breast aware”) can help find cancer in the treated or other breast.

If you have had a double mastectomy with or without a reconstruction, you should also regularly look at and feel your new shape and get to know your “new normal”. Tell your specialist, breast care nurse or GP if you notice any changes. Breast cancer can also return in other parts of the body, such as the bones, liver or lungs. Most symptoms will not be a recurrence, but if you notice any changes to your health, see your doctor and let them know that you have had breast cancer.

It is important to continue taking the drugs your doctor prescribes, even months or years after your treatment. Talk to your doctor before you stop taking any drugs, as these drugs may be helping to stop the cancer returning.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA also operates a free counselling program. Call 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on

1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.