The skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body. It protects the body from injury, controls body temperature and prevents loss of body fluids.

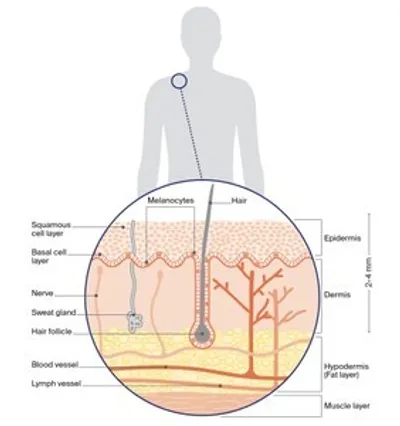

The 2 main layers of the skin are called the epidermis and the dermis. Below these is a layer of fatty tissue known as the hypodermis.

Epidermis

The epidermis is the top, outer layer of the skin. It is made up of several sublayers that work together to continually rebuild the surface of the skin. The main sublayers are the basal cell layer and the squamous cell layer.

Squamous cell layer – This sits above the basal cell layer. Basal cells that have matured move up into the squamous cell layer. Here they are known as squamous cells or keratinocyte cells. Squamous cells are the main type of cell found in the epidermis.

Basal cell layer – This is the lowest layer of the epidermis. It contains basal cells and cells called melanocytes. The melanocyte cells produce a dark pigment called melanin, which gives skin its colour. When skin is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, melanocytes make melanin to try to protect the skin from getting burnt. This is what causes skin to tan. When melanocytes cluster together, they form non-cancerous spots on the skin called moles or naevi.

Dermis

This layer of the skin sits below the epidermis. The dermis is made up of fibrous tissue and contains the roots of hairs (follicles), sweat glands, blood vessels, lymph vessels and nerves.

The layers of the skin

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about melanoma are below.

What is melanoma?

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer. It develops in the skin cells called melanocytes. Melanoma most often develops in areas that have been exposed to the sun. It can also start in areas that don’t receive much sun, such as the eye (uveal or ocular melanoma); nasal passages, mouth and genitals (mucosal melanoma); and the soles of the feet or palms of the hands, and under the nails (acral melanoma).

Other types of skin cancer, called non-melanoma skin cancers or keratinocyte cancers, are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These are far more common than melanoma. However, melanoma is considered more serious because it can spread to other parts of the body, especially if not found early.

How common is melanoma?

Australia and New Zealand have the highest rates of melanoma in the world. Each year in Australia, almost 19,000 people are diagnosed with invasive melanoma (it has spread into the dermis, the lower layer of the skin) and 28,000 people are diagnosed with melanoma in situ (it is only in the epidermis, the top layer). In Australia, melanoma is the second most common cancer in men and the third most common in women (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers).

What are the signs of melanoma?

The ABCD and EFG rule is a tool used by doctors to help them look for characteristics of skin damage when diagnosing melanomas.

ABCD signs

Asymmetry – Are the halves of each spot different?

Border – Are the edges uneven, scalloped or notched?

Colour – Are there differing shades and colour patches?

Diameter – Is the spot greater than 6 mm across, or is it smaller than 6 mm but growing larger?

EFG signs

Some types of melanoma, such as nodular and desmoplastic melanomas, don’t fit the ABCD guidelines.

Elevated – Is it raised?

Firm – Is it firm to touch?

Growing – Is it growing quickly?

How do I spot a melanoma?

New moles mostly appear during childhood and through to the age of 30 to 40. However, adults of any age can develop new or changing spots. It is important to get to know your skin and check it every 3 to 6 months.

To check your skin, make sure you are in a place with good light, undress completely and use a full-length mirror to check your whole body. For areas that are hard to see, use a handheld mirror or ask someone to help. It is also a good idea to take a photo of your moles and spots so that you can compare them with an older photo to see if one has changed.

How melanoma looks can vary greatly. Look for spots that are new, different from other spots, or raised, firm and growing. If you have lots of moles, a melanoma usually stands out and looks different from other moles. A melanoma is usually brown or black, but it can also be pink.

Even if your doctor has said a spot is benign in the past, check for any changes in shape, size or colour. If you notice a new or changing spot, get it checked as soon as possible by your doctor.

What causes melanoma?

Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the cause of most types of skin cancer. If unprotected skin is exposed to the sun when the UV index is 3 or above or to other UV radiation, the structure and behaviour of the cells can change. This can permanently damage the skin, and the damage builds up every time a person spends time unprotected in the sun.

UV radiation most often comes from the sun, but it can also come from artificial sources such as solariums (also known as tanning beds or sun lamps). Solariums are now banned for commercial use in Australia because research shows that people who use solariums have a much greater risk of developing melanoma.

Who is at risk?

While anyone can develop melanoma, the risk is higher for people who have:

- unprotected exposure to UV radiation when the UV index is 3 or above, particularly a pattern of short, intense periods of sun exposure and sunburn, such as on weekends and holidays

- had significant UV exposure when they were young

- lots of moles (naevi), especially if the moles have an irregular shape and uneven colour

- pale or freckled skin, especially if it burns easily and doesn’t tan

- fair or red hair, and blue or green eyes

- a previous melanoma or other type of skin cancer

- a strong family history of melanoma

- a weakened immune system due to medical conditions or from using immunosuppressive medicines for a long time.

Family history and melanoma

Less than 2% of melanomas are linked to an inherited faulty gene. You could have an inherited faulty gene if 2 or more close relatives (parent, sibling or child) have been diagnosed with melanoma, particularly if they were diagnosed with more than one melanoma, or if they were diagnosed with melanoma before the age of 40.

People with a strong family history of melanoma should take extra care with sun protection and regularly check their skin carefully for new moles or skin spots. From their early 20s, they should consider having a professional skin check by a doctor.

If you are concerned about family risk, talk to your doctor about being referred to a family cancer clinic. Visit the Centre for Genetics Education to find a family cancer clinic near you. To learn more, call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

What are the main types of melanoma?

Melanoma of the skin is known as cutaneous melanoma. The main subtypes of cutaneous melanoma are shown below. Some rarer types of melanoma start in other parts of the body. Mucosal melanoma can start in the tissues in the mouth, anus, urethra, vagina or nasal passages. Ocular melanoma can start inside the eye. Melanoma can also start in the central nervous system.

Superficial Spreading Melanoma

|

How common is it? |

Makes up 55–60% of melanomas. |

|

Who gets it? |

Most common type of melanoma in people under 40, but can occur at any age. |

|

What does it look like? |

Can start as a new brown or black spot that grows on the skin, or as an existing spot, freckle or mole that changes size, colour or shape. |

|

Where is it found? |

Can develop on any part of the body but especially the area between the shoulders and hip (trunk). |

|

How does it grow? |

Often grows slowly and becomes more dangerous when it invades the lower layer of the skin (dermis). |

Nodular Melanoma

|

How common is it? |

Makes up 10–15% of melanomas. |

|

Who gets it? |

Most commonly found in people over 65. |

|

What does it look like? |

Usually appears as a round, raised lump (nodule) on the skin that is pink, red, brown or black and feels firm to touch; may develop a crusty surface that bleeds easily. |

|

Where is it found? |

Usually found on sun-damaged skin. |

|

How does it grow? |

Often a fast-growing form of melanoma, spreading quickly into the lower layer of the skin (dermis). |

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma

|

How common is it? |

Makes up 10–15% of melanomas. |

|

Who gets it? |

Most people with this subtype are over 40. |

|

What does it look like? |

Begins as a flat, irrregular patch of discoloured skin which can be brown, pink, red or white. |

|

Where is it found? |

Mostly found on sun-damaged skin on the face, ears, neck or head. |

|

How does it grow? |

May grow slowly and superficially over many years before it grows deeper into the skin. |

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

|

How common is it? |

Makes up 1–2% of melanomas. |

|

Who gets it? |

Mostly affects people over 40 with dark skin such as those of African, Asian and Hispanic backgrounds. |

|

What does it look like? |

Often appears as a colourless or lightly coloured area, may be mistaken for a stain, bruise or unusual wart; in the nails, can look like a long streak of pigment. |

|

Where is it found? |

Most commonly found on the palms of the hands, on the soles of the feet, or under the fingernails or toenails. |

|

How does it grow? |

Tends to grow slowly until it invades the lower layer of the skin (dermis). |

Desmoplastic Melanoma

|

How common is it? |

Makes up 1–2% of melanomas. |

|

Who gets it? |

Mostly affects people over 60. |

|

What does it look like? |

Starts as a firm, growing lump, often the same colour as your skin; may be mistaken for a scar and can be difficult to diagnose. |

|

Where is it found? |

Mostly found on sun-damaged skin on the head or neck, including the lips, nose and ears. |

|

How does it grow? |

Tends to be slower to spread than other subtypes, but often diagnosed later; sometimes can invade or spread via nerves. |

Which health professionals will I see?

You will probably start by seeing your general practitioner (GP). You may see a GP at a general practice, medical centre or skin cancer clinic. Skin cancer clinics are run by GPs with an interest in skin cancer.

If a GP diagnoses or suspects melanoma, they may remove the spot themselves or refer you to another doctor, such as a dermatologist or surgeon, for the biopsy. If there’s a waiting list, your GP can ask for an earlier appointment if necessary.

Your GP may arrange further tests. Depending on the nature of the melanoma and their expertise, the GP may recommend ways to treat it, or refer you to a dermatologist or surgeon who will manage your care. In more complex cases, treatment options may be discussed at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

Attending a melanoma unit

Management and treatment for advanced melanoma can be complex. People with advanced melanoma – as well as some diagnosed with earlier stage melanoma – can benefit from being treated in a cancer centre that has doctors who specialise in treating advanced melanoma.

Cancer centres are located at hospitals in major cities around Australia. You will be able to see a range of health professionals, called a multidisciplinary team, who specialise in different aspects of your care.

To find a multidisciplinary melanoma unit near you, check with your doctor or call Cancer Council 13 11 20.

Health professionals you may see

GP – checks skin for suspicious spots, may remove potential skin cancers and refer you to specialists.

Dermatologist – diagnoses, treats and manages skin conditions, including skin cancer.

General surgeon – performs surgery to remove early melanoma and lymph nodes, and to reconstruct the skin.

Reconstructive (plastic) surgeon – performs surgery that restores, repairs or reconstructs the body’s appearance and function; may also remove lymph nodes.

Surgical oncologist – performs surgery to remove melanoma and conducts more complex surgery on the lymph nodes and other organs; can be a general surgeon or a reconstructive surgeon.

Medical oncologist – treats melanoma with drug therapies such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy.

Cancer care coordinator – coordinates care, liaises with MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS).

Counsellor, social worker, psychologist – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment.

Physiotherapist, occupational therapist – assist with physical and practical issues, including restoring movement and mobility after treatment and recommending aids and equipment.

Palliative care specialist and nurse – work closely with the GP and cancer team to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life.

How is melanoma diagnosed?

The first step in diagnosing a melanoma is a close examination of the spot.

If the spot looks suspicious, the doctor will remove it so it can be checked in a laboratory. In some cases, further tests will be arranged.

Physical examination

If you notice any changed or suspicious spots, see your GP. Your doctor will look carefully at your skin and ask if you or your family have a history of melanoma. The doctor will consider the signs known as the ABCD and EFG guidelines and examine the spot more closely using a method called dermoscopy – this involves using a handheld magnifying instrument called a dermatoscope.

People with a high risk of developing melanoma and those with multiple moles may have photos taken of all their skin to make it easier to look for changes over time. This is known as total body photography. Not everyone needs total body photography.

Removing the spot (excision biopsy)

If the doctor suspects that a spot on your skin may be melanoma, the whole spot is removed (excision biopsy). While this is the preferred type of biopsy to remove the spot, other types of biopsy may be used.

An excision biopsy is usually a simple procedure done in your doctor’s office. Your GP may do this procedure, or you may be referred to a dermatologist or surgeon. For the procedure, you will have an injection of local anaesthetic into the area around the spot to numb the site.

The doctor will use a scalpel to remove the spot and a small amount of healthy tissue (2 mm margin) around it. It is recommended that the entire spot is removed rather than a small sample. This helps ensure an accurate diagnosis of any melanoma found. The wound will usually be closed with stitches and covered with a dressing. You’ll be told how to look after the wound and dressing.

A doctor called a pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope to work out if it contains melanoma cells. Results are usually ready within a week.

You will have a follow-up appointment to check the wound and remove the stitches. If a diagnosis of melanoma is confirmed, you will probably need a second operation to remove more tissue. This is called a wide local excision.

Checking lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are part of your body’s lymphatic system. This is a network of vessels, tissues and organs that helps to protect the body against disease and infection. Sometimes melanoma can travel through the lymphatic system to other parts of the body. To work out if the melanoma has spread, your doctor may suggest tests to check the lymph nodes. Not everyone needs these tests.

Ultrasound – a scan used if lymph nodes feel enlarged.

Needle biopsy – if lymph nodes feel enlarged or look abnormal on ultrasound, you will probably have a fine needle biopsy. This uses a thin needle to take a sample of cells from the enlarged lymph node.

Sometimes, a thicker sample needs to be removed (core biopsy). The sample is examined under a microscope to see if it contains cancer cells. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, you may be offered a combination of surgery to remove the lymph nodes (lymph node dissection) and drug therapy. This may be performed at a specialist melanoma unit.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy – When melanoma spreads, often the sentinel nodes are the first place it spreads to. A sentinel lymph node biopsy removes them so they can be checked for melanoma cells.

You may be offered a sentinel lymph node biopsy if you have no lymph nodes that feel enlarged and the melanoma is more than 1 mm thick (Breslow thickness) or is less than 1 mm with high-risk features. A sentinel node biopsy helps find melanoma in the lymph nodes before they become swollen. If your doctor thinks you need a sentinel node biopsy, you will have it at the same time as the wide local excision.

To find the sentinel lymph node, a small amount of radioactive dye is injected into the area where the initial melanoma was found. During the surgery, blue dye is also injected – any lymph nodes that take up both dyes will be removed so a pathologist can check them under the microscope for cancer cells.

If cancer cells are found in a removed lymph node, you may have further tests such as CT or PET–CT scans. The results of this biopsy can help predict the risk of melanoma spreading to other parts of the body. This information helps the multidisciplinary team plan your treatment options and decide whether to recommend drug therapies such as targeted therapy or immunotherapy.

Understanding the pathology report

The report from the pathologist is a summary of information about the melanoma that helps determine the diagnosis, the stage, the recommended treatment and the expected outcome (prognosis). You can ask your doctor for a copy of the pathology report. It may include:

Breslow thickness – This measures the thickness of the tumour in millimetres to its deepest point in the skin. The thicker a melanoma, the higher the risk it could return (recur) or spread to other parts of the body.

Melanomas are classified as:

- in situ – found only in the top layer of the skin (epidermis)

- thin – less than 1 mm

- intermediate – 1–4 mm

- thick – greater than 4 mm.

Ulceration – The breakdown or loss of the outer layer of skin over the tumour is known as ulceration. It is a sign the tumour is growing quickly.

Mitotic rate – Mitosis is the process by which one cell divides into 2. The pathologist counts the number of actively dividing cells within a square millimetre to calculate how quickly the melanoma cells are dividing.

Clark level – This describes how many layers of skin the tumour has grown through. It is rated on a scale of 1–5, with 1 the shallowest and 5 the deepest. The Clark level is less accurate and not used as often now.

Margin – This is the area of normal skin around the melanoma. The report will describe how wide the margin is and whether any melanoma cells were found at the edge of the removed tissue.

Regression – This refers to inflammation or scar tissue in the melanoma, which suggests that some melanoma cells have been destroyed by the immune system. In the report, the presence of lymphocytes (immune cells) in the melanoma indicates inflammation.

Lymphovascular invasion – This means that melanoma cells have entered the lymphatic system or blood vessels.

Satellites – These are small areas of melanoma found separate from, but less than 2 cm away from, the primary melanoma.

Perineural invasion – This is when melanoma cells are found in and around the nerves of the skin.

Further tests

Often, only a biopsy is needed to diagnose melanoma. If pathology results show the melanoma is thicker, you will have scans to find out more about the melanoma. You may also have other tests during treatment or as part of follow-up care after treatment finishes.

Confocal microscopy – This is a non-invasive type of imaging that allows a dermatologist to see a very detailed and magnified view of your skin cells. The person doing the confocal microscopy uses a handheld device that sends out a low-power laser beam of light, which magnifies cells in the skin by about 1000 times.

Ultrasound – The person doing the ultrasound will move a handheld device called a transducer across part of your body. The transducer sends out soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or tumour. A computer turns the echoes into pictures.

CT scan – A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-ray beams to create detailed, cross-sectional pictures. Before the scan, you may have an injection of a liquid dye (called contrast) to make the pictures clearer. The CT scanner is large and round like a doughnut. You will need to lie still on a table while the scanner moves around you.

MRI scan – An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional pictures. Before the scan, you may have an injection of a liquid dye (called contrast) to make the pictures clearer. During the scan, you will lie on an examination table that slides into a large metal tube that is open at both ends. The noisy and narrow MRI machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. Let your medical team know beforehand if you are anxious – you may be offered medicine to help you relax.

PET–CT scan – A PET (positron emission tomography) scan combined with a CT scan is a specialised imaging test. A glucose solution containing a small amount of radioactive material will be injected into a vein in your arm. Cancer cells can show up brighter on the scan because they take up more of the glucose solution than normal cells do.

Staging melanoma

The pathology report and any other test results will show whether you have melanoma and whether it has spread to other parts of the body. Called staging, it helps your team recommend the most appropriate treatment for you. The melanoma will be given an overall stage of 0–4 (usually written in Roman numerals as 0, I, II, III or IV).

Stages of melanoma

Stage 0 (in situ) – It is confined to the top, outer layer of the skin (epidermis). Very early or localised melanoma.

Stage 1 – It has not moved beyond the primary site and is less than 1 mm thick with or without ulceration, or 1–2 mm thick without ulceration. Early or localised melanoma.

Stage 2 – It has not moved beyond the primary site and is 1.1–2 mm Breslow thickness with ulceration, or more than 2 mm thick with or without ulceration. Early or localised melanoma.

Stage 3 – It has spread from the primary site to nearby lymph nodes or surrounding tissue (in-transit disease). Locoregional melanoma.

Stage 4 – It has spread to distant skin or tissues and/or other parts of the body, such as lungs, brain, bone, or distant lymph nodes. Advanced or metastatic melanoma.

Genomic testing

If the melanoma has spread (stage 3 or 4), you may have genomic tests for a particular gene change (mutation). These gene mutations are due to changes in cancer cells – they occur during a person’s lifetime and are not the same thing as genes passed through families.

About 50% of people with melanoma have a mutation in the BRAF gene, which makes the cancer cells grow and divide faster. About 15% have a mutation in the NRAS gene, which controls how cells divide. C-KIT is a rare mutation affecting less than 4% of people with melanoma.

Genomic tests can be done on the tumour tissue sample removed during surgery. The test results will help doctors work out whether particular drug therapies may be useful.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease. Instead, your doctor can discuss any concerns you may have.

Melanoma can be treated most effectively in its early stages when it is still confined to the top layer of the skin (epidermis). The deeper a melanoma grows into the lower layer of the skin (dermis), the greater the risk that it could spread to nearby lymph nodes or other organs.

In recent years, newer drug treatments such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy have improved the prognosis for people with melanoma that has spread from the primary site (advanced or metastatic melanoma) or is at very high risk of spreading.

Treatment for early melanoma

Surgery is the most common treatment for melanoma that is found early (stages 0–2 or localised melanoma).

If found early, 90% of melanomas can be cured with surgery alone. If the risk of the melanoma spreading is high or it has spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues (stage 3 or regional melanoma), treatment may also include removing lymph nodes and additional (adjuvant) treatments. Your doctor may suggest you have drug treatment before surgery (neoadjuvant treatment).

Surgery

Surgery (wide local excision)

After an excision biopsy, most people diagnosed with melanoma will require a second surgery to remove more skin from around the melanoma. This is known as a wide local excision and is the main treatment for early melanoma.

Removing more skin around the melanoma reduces the risk of it coming back (recurring) at that site. The width of the margin is usually 5–10 mm, depending on the type, thickness and location of the melanoma. For thicker tumours, or tumours with certain characteristics, a wider margin of up to 20 mm may be advised.

A wide local excision is often performed as a day procedure, so you can go home soon after the surgery if there are no complications. If the melanoma is thicker than 1 mm or is considered to have a high risk of spreading to the lymph nodes, the doctor will discuss the risks and benefits of having a sentinel lymph node biopsy. If you need a sentinel node biopsy, it is done at the same time as the wide local excision.

Checking for a clear margin

After a wide local excision, the tissue removed from around the melanoma will be sent to a laboratory. The pathologist will check that the required margin has been taken – this is called a clear margin. If the margins need to be wider, you may need to have further surgery to remove more tissue.

Repairing the wound

The wound is often closed with stitches. You will have a scar but this will usually become less noticeable with time. If a large area of skin is removed, the surgeon may repair the wound using skin from another part of your body. This can be done in 2 ways:

Skin flap – Nearby skin and fatty tissue are lifted and moved over the wound from the edges and stitched.

Skin graft – A layer of skin is taken from another part of your body (most often the thigh or neck) and placed over the area where the melanoma was removed. The skin grows back quickly, usually over a few weeks.

Whether the surgeon does a skin flap or graft will depend on a number of factors, including where the melanoma was and how much tissue has been removed. In either case, the wound will be covered with a dressing. After several days, the doctor will check to see if the wound is healing properly. If you had a skin graft, you will also have a dressing on any area that had skin removed for the graft.

What to expect after surgery

Most people recover quickly after a wide local excision to remove a melanoma, but you will need to keep the wound clean.

Pain relief – The area around the wide local excision may feel tight and tender for a few days. Your doctor will prescribe pain medicine if necessary.

Wound care – Your treatment team will tell you how to keep the wound clean to prevent it from becoming infected. Occasionally, the original skin flap or graft doesn’t heal. In this case, you will need to either have a dressing on the wound for longer or have another procedure to create a new flap or graft.

Skin change – If you have a skin graft, the area that had skin removed may look red and raw immediately after the operation. Over a few weeks to months, this area will heal, and the redness will fade.

Recovery time – The time it takes to recover will vary depending on the thickness of the melanoma and how much surgery was required. Most people recover in 1–2 weeks. Ask your doctor how long to wait before returning to your usual exercise and activities.

When to seek advice – Talk to your doctor if you have any unexpected bleeding, bruising, infection, scarring or numbness after surgery.

Removing lymph nodes

Many people with early melanoma will not need to have any lymph nodes removed. But if lymph nodes do need to be removed, these are a few ways it can be done:

Sentinel lymph node biopsy – If the melanoma is thicker than 1 mm or has high-risk features, you may have a sentinel lymph node biopsy at the same time as the wide local excision.

Further scans and treatment – If a sentinel lymph node biopsy shows melanoma in the removed node, you will need to have regular imaging scans to check that the melanoma has not come back or spread. You may also be offered drug therapy to reduce the risk of the melanoma returning.

Lymph node dissection – If your lymph nodes feel or look swollen, and a fine needle biopsy confirms that a lymph node contains melanoma, you may need to have all the lymph nodes in that area removed under a general anaesthetic. This operation is called a lymph node dissection or lymphadenectomy, and may mean a longer stay in hospital.

Side effects of lymph node removal

Having your lymph nodes removed can cause side effects. These can be milder if you have a sentinel lymph node biopsy compared with having all of the lymph nodes from an area removed (lymph node dissection).

Wound pain – Most people will have some pain after the operation, which usually improves as the wound heals. Sometimes, the pain may last longer or be ongoing. Talk to your treatment team about how to manage any pain.

Neck/shoulder/hip stiffness and pain – These are the most common problems if lymph nodes in your neck, armpit or groin were removed. You may find that you cannot move the affected area as freely as you could before the surgery. It may help to do gentle exercises or ask your GP or treatment team to refer you to a physiotherapist.

Seroma/lymphocele – This is a collection of fluid in the area where the lymph nodes have been removed. It is a common side effect and usually appears 7–10 days after surgery. It usually gets better after a few weeks, but sometimes fluid may need draining with a needle.

Lymphoedema – This is a swelling of the neck, arm or leg that may appear after the lymph nodes are removed. Lymphoedema happens when lymph fluid builds up in the affected part of the body because the treatment has damaged or blocked the lymphatic system.

Managing lymphoedema

Your risk of developing lymphoedema depends on the extent of the surgery and whether you’ve had radiation therapy.

Lymphoedema can start a few weeks after treatment. Sometimes it develops several years later. Although it may be permanent, it can usually be managed, especially if treated at the earliest sign of swelling or heaviness.

A lymphoedema practitioner can help you manage lymphoedema. To find a trained practitioner, visit the Australasian Lymphology Association or ask your doctor for a referral. You may need to wear a professionally fitted compression garment. Massage and regular exercise, such as swimming, cycling or yoga, can help the lymph fluid flow. Keeping the skin healthy can help reduce the risk of infection.

Further treatment before or after surgery

If there’s a risk that the melanoma could come back (recur) after surgery, other treatments are sometimes used to reduce the risk. These are known as neoadjuvant treatments if used before surgery and adjuvant (or additional) treatments if used after. They may be used alone or together.

Treatments that enter the bloodstream are used if there is a risk a tumour will come back in other parts of the body (further from the regional sites). These are known as drug therapies or systemic treatment.

The main systemic treatments for melanoma are:

- immunotherapy – drugs that use the body’s own immune system to recognise and fight some types of cancer cells; can be used before or after surgery

- targeted therapy – drugs that attack specific features within cancer cells, known as molecular targets, to stop the cancer growing and spreading; usually given after surgery.

Rarely, radiation therapy will be used after surgery if there’s a risk the tumour could come back at the original site or to the nearby lymph nodes. Radiation therapy is the use of targeted radiation to damage or kill cancer cells in a particular area of the body.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Immunotherapy’

Treatment for advanced melanoma

When melanoma has spread to distant lymph nodes, internal organs or bones (stage 4), it is known as advanced or metastatic melanoma.

Treatment may include immunotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy and surgery. Palliative treatment may also be offered to help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Since more effective treatments are now available, chemotherapy is rarely used to treat melanoma.

You will be offered a treatment plan based on factors such as the features of the melanoma, where it has spread and any symptoms you have. New developments are occurring all the time, and you may be able to get new treatments through clinical trials.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors use the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Checkpoint inhibitors remove barriers that stop the immune system from finding and attacking cancer.

Checkpoint inhibitors used for advanced melanoma include relatlimab, ipilimumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Sometimes more than one drug is used, with different combinations working for different people.

You will usually have immunotherapy as an outpatient, which means you visit a treatment centre for the day. In most cases, the immunotherapy drugs are given into a vein intravenously).

You may have treatment every 2–6 weeks in a repeating cycle for up to 2 years, but this depends on how the melanoma responds to the drugs and any side effects you may have.

Immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors has worked well for some people with melanoma, but it does not help everyone. While most people treated with checkpoint inhibitors have had advanced cancer, immunotherapy is now available for some people with earlier stage melanoma.

Other immunotherapy treatments are being tested in clinical trials. Talk to your doctor about whether immunotherapy is an option for you.

Checkpoint inhibitors can take weeks or months to start working, depending on how your immune system and the cancer respond. Sometimes their effects keep working long after treatment stops, but this varies from person to person. Other times cancer cells can become resistant to the treatment even if it works at first.

Possible side effects of immunotherapy

The side effects of immunotherapy drugs will vary depending on which drugs you are given and can be unpredictable. Immunotherapy can cause inflammation in any of the organs in the body, which can lead to side effects such as tiredness, joint pain, diarrhoea, and an itchy rash or other skin problems. The inflammation can lead to more serious side effects in some people, and in rare cases, this can be life threatening, but these side effects will be monitored closely and managed quickly.

You may have side effects within days of starting immunotherapy, but more often they occur many weeks or months later. It is important to discuss any side effects with your treatment team as soon as they appear so they can be managed appropriately. When side effects are treated early, they are likely to be less severe and last for a shorter time.

Delaying or stopping treatment for a side effect does not mean immunotherapy will stop working. Many patients stop treatment after only one or a few treatments and their melanoma remains controlled years later without further treatment.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a drug treatment that targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. Your doctor will check if the melanoma you have has a specific mutation before offering you a targeted therapy drug.

About 50% of people with melanoma have a BRAF mutation. This mutation can be blocked by giving BRAF and MEK inhibitor drugs – a treatment shown to be effective for people with advanced melanoma that has the BRAF mutation. Targeted therapy drugs are generally taken as tablets (orally) once or twice a day, often for many months or even years.

A good response from targeted therapy will make cancer that can be seen on a scan shrink or even disappear completely on scans. In some cases, the cancer remains stable, which means it doesn’t grow in size. Cancer cells can sometimes become resistant to targeted therapy drugs over time. If this happens, your doctor may suggest trying another type of treatment.

Possible side effects of targeted therapy

The side effects of targeted therapy will vary depending on which drugs you are given. Common side effects include fever, tiredness, joint pain, rash and other skin problems, loss of appetite, nausea and diarrhoea. Ask your treatment team how you can deal with any side effects.

Radiation therapy

Also known as radiotherapy, radiation therapy is the use of targeted radiation to kill or damage cancer cells. Radiation therapy may be offered on its own or with other treatments. It can be used after surgery to stop melanoma coming back. It can also be used to help relieve pain and other symptoms caused by melanoma that has spread – for example, to the brain or bone (palliative treatment).

Before starting treatment, you will have a CT or MRI scan at a planning appointment. The radiation therapist may make some small permanent or temporary marks (tattoos) on your skin so that the same area is targeted during each treatment session. If you are having radiation therapy to the brain, a plastic mask will be custom-made to fit you. It helps keep your head still so that the radiation is targeted at the same area each session. Each treatment session takes about 30 minutes and is usually given daily for 1–4 weeks. For the treatment, you will lie on a table under a machine that aims radiation at the affected part of your body.

In some cases, you may be offered a specialised type of radiation therapy that delivers extremely precise, tightly focused beams of high-dose radiation onto the tumour from many different angles. This is called stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) when used on the brain, and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) when used on other parts of the body. SBRT usually involves 3–5 treatment sessions over 1–2 weeks.

Side effects of radiation therapy

The side effects that you experience will depend on the part of the body that receives radiation therapy, the dose of radiation you receive and how long you have treatment. Many people will have temporary side effects, which may build up over time. Common side effects during or immediately after radiation therapy include tiredness, and the skin in the treatment area becoming red and sore. Ask your treatment team for advice about dealing with any side effects.

Surgery

In some cases, surgery may be recommended for people with advanced melanoma. It is used to remove melanoma from the skin, lymph nodes, or other organs such as the lung, bowel or brain. Your suitability for surgery will be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting.

Talk to your treatment team about what the surgery involves and what recovery will be like. Side effects will depend on the type of surgery, but often include pain and risk of infection

Palliative treatment

In some cases of advanced melanoma, the treatment team may talk to you about palliative treatment. Palliative treatment aims to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer without trying to cure the disease. It can be used at any stage of advanced cancer and does not mean giving up hope. Some people have palliative treatment as well as active treatment of the melanoma.

When used as palliative treatment, radiation therapy and medicines can help manage symptoms caused by advanced melanoma, such as pain, nausea and shortness of breath.

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Looking after your skin

Most melanomas are caused by exposure to the sun’s UV radiation.

After a diagnosis of melanoma, it is especially important to check your skin regularly and follow SunSmart behaviour. When UV levels are 3 or above, use all or as many of the following measures as possible to protect your skin.

Slip on clothing – Wear clothing that covers your shoulders, neck, arms, legs and body. Choose closely woven fabric or fabric with a high ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) rating, and darker fabrics where possible.

Slop on sunscreen – Use SPF 50 or SPF 50+ broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen and apply every morning. Reapply 20 minutes before going outdoors and reapply every 2 hours, or after swimming, sweating or any activity that causes you to rub it off. For an adult, apply about 7 teaspoons of sunscreen for a full body application – 1 teaspoon for each arm, leg, front of body, back of body, and the face, neck and ears.

Slap on a hat – Wear a hat that shades your face, neck and ears. This includes legionnaire, broad-brimmed and bucket hats. Check to make sure the hat meets the Australian Standard. Choose fabric with a close weave that doesn’t let the light through. Baseball caps and sun visors do not offer enough protection.

Seek shade – Use shade from trees, umbrellas, buildings or any type of canopy. UV radiation is reflective and bounces off surfaces, such as concrete, water, sand and snow, so shade should never be the only form of sun protection used. If you can see the sky through the shade, even if the direct sun is blocked, the shade will not completely protect you from UV radiation.

Slide on sunglasses – Make sure you protect your eyes with sunglasses that meet the Australian Standard (with a lens category of 2, 3 or 4). Wraparound styles are best. Sunglasses should be worn all year round to protect both the eyes and the delicate skin around the eyes.

Don’t use solariums – It is not safe to use solariums. Also known as tanning beds or sun lamps, solariums give off artificial UV radiation and are banned for commercial use in Australia.

Check daily sun protection times – Each day, use the free SunSmart Global UV app to check the recommended sun protection times in your local area, and use sun protection when the UV is 3 or above. You can also find sun protection times at the Bureau of Meteorology, the BOM Weather app or in the weather section of daily newspapers.

Understanding sun protection

After a melanoma diagnosis, you need to take special care to protect your skin from the sun’s UV radiation. This will reduce your risk of further melanomas.

The UV Index shows the intensity of the sun’s UV radiation. A UV index of 3 or above means that UV levels are high enough to damage unprotected skin, and you need to use all 5 types of sun protection. The recommended daily sun protection times are the times of day UV levels are expected to be 3 or higher. These will vary according to where you live and the time of year.

Sun exposure and vitamin D

UV radiation from the sun causes skin cancer, but it is also the best source of vitamin D. People need vitamin D to develop and maintain strong, healthy bones. The body can absorb only a set amount of vitamin D at a time. Most people get enough vitamin D through incidental exposure to the sun, while using sun protection. When the UV Index is 3 or above, this may mean spending just a few minutes outdoors on most days of the week, depending on where in Australia you live and the time of year. However, people with naturally very dark skin tones, who do not burn, may need longer sun exposure to get enough vitamin D.

After a diagnosis of melanoma, talk to your doctor about the best ways to get enough vitamin D while reducing your risk of getting more melanomas. Your doctor may advise you to limit your sun exposure as much as possible when the UV Index is 3 or above. In some cases, this may mean you don’t get enough sun exposure to maintain your vitamin D levels. Your doctor may advise you to take a supplement. Overexposure to UV is never recommended.

Life after treatment

If you had early melanoma, your main concern after treatment may be how to protect your skin and watch for any new melanomas.

If you had a high-risk or advanced melanoma, you may find that the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment.

You may have mixed feelings, and worry that every ache and pain means the melanoma is coming back. Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had melanoma, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After you have had one melanoma, you have about 5 times the risk of developing a new melanoma compared with the average person of the same age. It is important to regularly check your skin for any changes, go to your follow-up appointments and take extra care with sun protection. People with advanced melanoma will probably have more frequent follow-up appointments.

At your appointments, your doctor will check the treated area and your lymph nodes. Your doctor will also check the rest of your skin for any new melanomas. You may need to have CT scans or PET–CT scans before follow-up appointments.

You may feel anxious before a follow-up appointment or test. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council 13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

What if the melanoma returns?

For people with early melanoma, it will usually not come back (recur) after treatment, although they do have a higher risk of developing a new melanoma. The risk of the treated melanoma returning is higher for people with regional melanoma (stage 3). Recurrence can occur at the site where the melanoma was removed; in the lymph nodes; or in other parts of the body, such as the lung, liver or brain.

If the melanoma returns, your doctor will discuss the treatment options with you. These will depend on where the melanoma is, as well as the number of sites, its extent and your general health. You may be offered immunotherapy, targeted therapy or the option to join a clinical trial.

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer. Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication – even for a short time – may help.

Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on 1300 22 4636. For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.