The liver

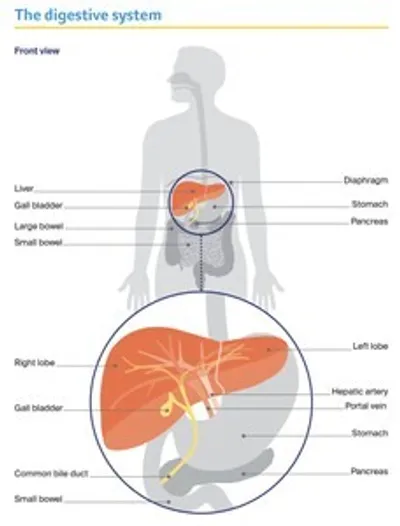

The largest organ inside the body, the liver is about the size of a football. It is part of the digestive system, working with the gall bladder and pancreas to help break down food and turn it into energy.

The liver has many important jobs, including:

- storing sugars and fats, so they can be used for energy

- producing bile to help dissolve fat so it can be easily digested

- making proteins to help blood clot and to balance fluid in the body

- breaking down harmful substances, such as drugs and alcohol.

The liver is found on the right side of the abdomen (belly), sitting just above the stomach and under the rib cage. It is divided into two main sections – the right and left lobes.

How the liver works

Blood flows into the liver from the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The hepatic artery carries blood from the heart. The portal vein carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver.

Bile is carried between the liver, the gall bladder and the first part of the small bowel (the duodenum) by a series of tubes called bile ducts. The common bile duct carries bile from the liver and the gall bladder to the bowel, where the bile helps to break down and absorb fats and other nutrients from food.

The liver can continue to work when only a small part is healthy. A healthy liver may be able to repair itself if it is injured or part of it is surgically removed during cancer treatment.

Key questions

Answers to some key questions about liver cancer are below.

What is primary liver cancer?

Primary liver cancer is a malignant (cancerous) tumour that starts in the liver. The most common type of primary liver cancer in adults is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC starts in the hepatocytes, the main type of liver cell. This information is only about HCC.

Less common types of primary liver cancer include:

- cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct cancer – starts in the bile ducts

- angiosarcoma and hemangiosarcoma – rare types of liver cancer that start in the blood vessels

- hepatoblastoma – a rare type of liver cancer that affects only young children.

Cancers in the liver can be either a primary or secondary cancer. The two types of cancer are different. Secondary liver cancer is cancer that has started in another part of the body and spread to the liver. It is more common than primary liver cancer in Australia. If you are unsure if you have primary or secondary liver cancer, check with your doctor.

Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma)

This uncommon form of primary liver cancer accounts for about 10–15% of all liver cancers worldwide. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma) starts in the cells lining the ducts that carry bile between the liver, gall bladder and bowel. Most risk factors are similar to those of HCC, but exposure to certain chemicals in the print industry may also increase the risk of developing bile duct cancer.

See our information about Gall Bladder Cancer which covers both gall bladder and bile duct cancer.

How common is liver cancer?

In Australia, more than 3000 people are diagnosed with primary liver cancer each year, with almost three times more men than women affected. The rate of primary liver cancer has almost doubled since 2002, which is possibly due to increasing rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, hepatitis B and C infections, drinking too much alcohol, and an ageing population. About 80% of cases occur in people aged 60 and over.

What are the symptoms?

Liver cancer often doesn’t cause any symptoms in the early stages, and cancer that is diagnosed and treated before symptoms appear often has very good outcomes.

As the cancer grows or spreads, it may cause symptoms such as:

- weakness and tiredness (fatigue)

- pain in the abdomen (belly) or below the right shoulder blade

- a hard lump on the right side of the abdomen

- appetite loss, feeling sick (nausea), or unexplained weight loss

- yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice)

- dark urine (wee) and pale faeces (poo)

- itchy skin

- a swollen abdomen caused by fluid build-up (ascites).

What are the risk factors?

Primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma or HCC) most often develops in people with underlying liver disease, usually cirrhosis. In cirrhosis, healthy liver cells are replaced by scar tissue, and benign nodules (non-cancerous lumps) form throughout the liver. As this gets worse (advanced cirrhosis), the liver stops working properly.

Cirrhosis may be caused by: long-term (chronic) infection with hepatitis B or C virus; drinking too much alcohol; metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) as a result of obesity and/or type 2 diabetes; having too much iron in the bloodstream (haemochromatosis); or certain autoimmune conditions (e.g. primary biliary cholangitis).

A small but increasing number of people are developing liver cancer without cirrhosis. This may occur in those with long-term hepatitis B infection, or with liver disease related to obesity or type 2 diabetes.

Other risk factors for liver cancer are smoking tobacco or having a family history of HCC. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and migrants from countries with higher rates of hepatitis B infection (e.g. countries in the Asia–Pacific region and Sub-Saharan Africa) are also at greater risk of developing primary liver cancer.

The more risk factors a person has, the greater the chance of developing liver cancer.

What is the link between hepatitis and liver cancer?

Worldwide, up to 8 in 10 cases of liver cancer (HCC) can be linked to infection with the hepatitis B or C virus (viral hepatitis). This is changing as vaccinations and effective treatments for viral hepatitis are helping to reduce the rates of hepatitis-related liver cancer.

How hepatitis spreads

Hepatitis B and C spread through contact with infected blood, semen or other body fluids.

The most common way hepatitis B spreads is from an infected mother to a baby during birth. Hepatitis B can also be transmitted during unprotected sex with an infected partner, or by sharing personal items, such as razors or needles, with an infected person.

Hepatitis C is usually transmitted through the sharing of needles during illicit drug use, tattooing, sharing personal items, or contaminated medical equipment.

Viral hepatitis infects the liver cells (hepatocytes). When the body’s immune system attacks the virus, the liver becomes inflamed. Infection that lasts for more than six months may lead to liver damage (cirrhosis), which increases the risk of primary liver cancer. Importantly, people with cirrhosis should have long-term monitoring for liver cancer.

Preventing hepatitis

All babies in Australia are offered the hepatitis B vaccine at birth. To further prevent the spread of hepatitis B, at-risk people should also be vaccinated. This includes: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; people from countries with higher rates of hepatitis B; people living with someone with hepatitis; people who are immunocompromised; and health care workers.

If you already have hepatitis B, vaccination won’t be helpful, but you will usually have regular tests to ensure you don’t develop cancer or other liver problems. If you also have signs of liver damage, you may be offered antiviral medicines to help prevent further damage.

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C infection, but effective medicines are available and the virus can often be cured. While this treatment can lower the risk of primary liver cancer, it does not eliminate it.

Which health professionals will I see?

Your general practitioner (GP) will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms or to follow up abnormal results from ultrasound or blood tests that have been done to check for liver cancer. If these tests show that you have liver cancer – or there is concern about possible cancer – you will usually be referred to a specialist. This is likely to be a hepatobiliary surgeon, gastroenterologist or hepatologist. The specialist will arrange further tests.

If liver cancer is diagnosed, the specialist will consider treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care. Primary liver cancer is challenging to treat and it is recommended that you are treated in a specialist treatment centre if possible.

Health professionals you may see

Hepatobiliary surgeon – operates on the liver, gall bladder, pancreas and surrounding organs

Gastroenterologist – diagnoses and treats disorders of the digestive system, including liver cancer; may treat liver cancer with drug therapies

Hepatologist – a gastroenterologist specialising in liver disease

Interventional radiologist – analyses x-rays and scans, may also perform a biopsy under ultrasound or CT and deliver some treatments

Medical oncologist – treats cancer with drug therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy (systemic treatment)

Radiation oncologist – treats cancer by prescribing and overseeing a course of radiation therapy

Cancer care coordinator – coordinates your care, liaises with other members of the MDT and supports you and your family throughout treatment; care may also be coordinated by a clinical

nurse consultant (CNC) or clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

Nurse, hepatology nurse – administer drugs and provide care, information and support; a hepatology nurse specialises in liver cancer

Occupational therapist – assists in adapting your living and working environment to help you resume usual activities after treatment

Physiotherapist, exercise physiologist – help restore movement and mobility, and improve

fitness and wellbeing

Social worker – links you to support services and helps you with emotional, practical and financial issues

Psychiatrist, counsellor, psychologist – help you manage your emotional response to diagnosis and treatment

Dietitian – helps with nutrition concerns and recommends changes to diet during treatment and recovery

Palliative care team – works closely with your GP and cancer team to help control symptoms and maintain quality of life; includes palliative care specialists and nurses, as well as other health professionals

How is liver cancer diagnosed?

Liver cancer may be diagnosed using several tests. These include blood tests and imaging scans. It is becoming more common for a tissue sample to also be tested. This is called a biopsy.

Blood tests

Blood tests alone cannot diagnose liver cancer, but they can help doctors work out what type of liver cancer may be present and how well the liver is working. Blood tests can also provide information on the type of liver disease that may be causing cirrhosis. Samples of your blood may be sent for the following tests.

Liver function tests (LFTs) – These tests measure the levels of several substances that show how well your liver is working. You may have liver function tests done before, during and after treatment.

Blood clotting tests – These check if the liver is making proteins that help the blood to clot. Low levels of these proteins increase your risk of bleeding.

Hepatitis and other liver tests – These check for hepatitis B and C, which can lead to liver cancer. Also, tests may be done to check for other possible causes of liver disease, such as too much iron in the bloodstream (haemochromatosis) or autoimmune hepatitis (when the body’s own immune system attacks the liver).

Tumour markers – Some blood tests look for proteins produced by cancer cells. These proteins are called tumour markers.

The most common tumour marker for primary liver cancer is called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). It may be higher in many, but not all, cases of primary liver cancer.

The AFP level may also be raised in people with conditions other than cancer, such as pregnancy, hepatitis and jaundice.

Imaging scans

Tests that take pictures of the inside of the body are known as imaging scans. An ultrasound scan is usually the imaging scan first used to look for liver cancer and to monitor people with cirrhosis.

An ultrasound scan alone cannot confirm a diagnosis of liver cancer, so you will also have one or more other scans. You may have some imaging scans more than once during diagnosis and again during treatment.

Ultrasound – An ultrasound scan is used to show if there is a tumour in the liver and how large it is. You will be asked not to eat or drink (fast) for about four hours before the ultrasound.

You will be asked to lie on your back for the scan and a gel will be spread onto your abdomen (belly). A small device called a transducer will be moved across the area. The transducer creates soundwaves that echo when they meet something solid, such as an organ or tumour. A computer turns these echoes into pictures.

An ultrasound is painless and usually takes only 15–20 minutes. If a solid lump is found, you will need other scans to show whether the lump is cancer. It is common to find non-cancerous (benign) lumps in the liver during an ultrasound.

CT scan – A CT (computerised tomography) scan uses x-ray beams to take detailed, cross-sectional pictures of the inside of your body. It helps show the features of the tumour in the liver. It may also show if the cancer has spread beyond the liver.

During the scan, a liquid dye (called contrast) is injected into one of your veins. This helps ensure that anything unusual can be seen more clearly. The dye may make you feel flushed and cause some discomfort in your abdomen. These reactions usually go away in a few minutes, but tell the team if you feel unwell.

Some people have an allergic reaction to the dye. They may need to take medicine before the scan to prevent such a reaction or avoid CT scans with dye altogether. If you have had an allergic reaction to dye in the past, tell the radiology practice before your appointment.

The CT scanner is large and round like a doughnut. You will need to lie still on a table while the scanner moves around you. It can take 10–30 minutes to get ready for the CT scan, but the scan itself takes only a few minutes and is painless.

MRI scan – An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional pictures of the liver and nearby organs. An MRI is used to show the size of the tumour and whether it is affecting the main blood vessels and bile ducts around the liver. This scan is particularly helpful for diagnosing small tumours.

During the scan, you will be injected with a dye (called contrast) that highlights the organs in your body. You will then be asked to lie on an examination table that slides completely into a large metal tube that is open at both ends.

The MRI scanner is noisy and narrow, and this can make some people feel anxious or uncomfortable (claustrophobic). If you think you may become distressed, mention this beforehand to your doctor or nurse. You may be given a mild sedative to help you relax, and you will usually be offered headphones or earplugs. A liver MRI scan may take up to 30 minutes.

Bone scan – If a liver transplant is a potential treatment and/or you have pain in the bones, you may need a bone scan to be sure the cancer has not spread (metastasised) to the bones.

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have had a reaction to contrast during previous scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Tissue sampling (biopsy)

A biopsy is when doctors remove a sample of cells or tissue from the affected area, and a pathologist examines the sample under a microscope to see if it contains cancer cells.

A biopsy is not always needed for diagnosis or when surgery is planned. If the diagnosis is not clear after the imaging scans, a biopsy may be useful. In the future, a biopsy may also provide information about the best treatment for each person (personalised medicine).

The liver has many blood vessels and there can be risk of bleeding with a biopsy. Before a biopsy, your blood may be tested to check if it clots normally. If you are taking blood-thinning medicines, ask your doctor if you need to stop taking them before and after the biopsy.

The sample of cells is usually collected with a core biopsy. Before the procedure, you will be given a local anaesthetic to numb the area, so you will still be awake but won’t feel pain.

The doctor will then pass a needle through the skin of the abdomen to remove a sample of tissue from the tumour. An ultrasound or CT scan helps the doctor guide the needle to the right spot. You may need to stay in hospital for a few hours or overnight if there is a high risk of bleeding.

Staging liver cancer

The stage of a cancer describes how large it is, where it is and whether it has spread in the body. Knowing the stage of a liver cancer helps doctors plan the best treatment for you. Primary liver cancer is staged using a method called the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. The system has 5 stages: 0 (very early); A (early); B (intermediate); C (advanced); D (end-stage).

To work out a cancer’s stage, your doctor will consider:

- the size of the tumour

- the number of tumours

- whether the cancer has spread to blood vessels, lymph nodes or other organs

- how well you are functioning in daily life and how active you are

- how well the liver is working (using a Child–Pugh score).

The Child–Pugh score records how well the liver is working. In this system, liver function is ranked as: A (some damage but is working normally); B (moderate damage, affecting how well the liver is working); or C (very damaged and not working well). A severely damaged liver may not be able to cope with some types of cancer treatment.

The doctor may also check for portal hypertension. Cirrhosis can sometimes increase the blood pressure in the portal vein, which carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver. This can affect how the cancer can be treated (e.g. surgery may not be an option in people with portal hypertension).

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your prognosis with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of a disease. To work out your prognosis, your doctor will consider:

- test results

- the type of liver cancer, its stage and how fast it is growing

- whether you have cirrhosis and how well the liver is working

- how well you respond to treatment

- other factors such as your age, fitness and overall health.

Discussing your prognosis and thinking about the future can be challenging and stressful. It is important to know that although the statistics for primary liver cancer can be frightening, they are based on an average of many cases and may not apply to your situation. Talk to your doctor about how to interpret any statistics that you come across.

The prognosis for liver cancer tends to be better when the cancer is still in the early stages, but liver cancer is often found later. Surgery to remove the cancer (liver resection) or a liver transplant may be an option for some people with primary liver cancer. Other treatments for liver cancer can significantly improve survival and can relieve symptoms to improve quality of life.

Treatment for liver cancer

There are many different types of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is the most common type of primary liver cancer.

The treatment recommended will depend on a range of factors, including:

- the size of the tumour

- how far it has spread within the liver and the body

- whether you have cirrhosis

- if any major blood vessels are involved

- your age and your general health.

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) may meet to discuss the best treatment options for you. Ask your doctor if your case has been discussed by an MDT.

Treatments for HCC that affects only the liver include:

- surgery – liver resection or liver transplant

- tumour ablation – heat or alcohol is used to destroy the tumour

- radiation therapy – stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), also known as stereotactic ablative body radiation (SABR), or selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT)

- transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) – chemotherapy drugs are delivered directly to the tumour via its blood supply.

If the cancer is advanced or has spread beyond the liver, you may be offered drug therapies such as immunotherapy or targeted therapy. Sometimes, if the liver is too damaged, you may be offered palliative treatment to manage symptoms and improve your quality of life.

Surgery

Liver surgery aims to remove all the cancer from the body. This may be done by removing the part of the liver affected by cancer (known as a liver resection or partial hepatectomy) or by removing the whole liver and replacing it with a liver from a donor (liver transplant). Your surgeon will talk to you about the most appropriate surgery for you, as well as the risks and any possible complications.

Informed consent – There are risks associated with any type of surgery. A surgeon needs your agreement (consent) before performing the operation. Receiving relevant information about the benefits and risks of surgery before agreeing to it is called informed consent.

Liver resection

The aim of a liver resection is to remove all cancer from the liver, as well as a margin of healthy tissue. Liver resection is usually performed in a specialist treatment centre.

A liver resection is suitable for only a small number of people with liver cancer. The liver needs to repair itself after the surgery, so a resection is only an option when the liver is working well.

People with no or early cirrhosis may be considered for surgery, but it is unlikely that people with more advanced cirrhosis will be offered surgery. Surgery is also not suitable for people with ascites or when the cancer has spread to major blood vessels.

Types of liver resection – The surgeon will consider the size and position of the tumour, as well as the health of the liver, to work out how much of the liver can be safely removed. The liver resection may be called a right or left hepatectomy (removes the right or left part of the liver) or a segmentectomy (removes a small section of the liver). In some cases, the gall bladder may also be removed, along with part of the muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen

(the diaphragm).

Portal vein embolisation (PVE) – Sometimes, the surgeon needs to remove so much of the liver that the remaining portion may not be large enough to recover. In this case, you may have a portal vein embolisation (PVE) about 4–8 weeks before the liver resection.

A PVE is performed by an interventional radiologist and is normally done under local anaesthetic.

How a liver resection is done – If you have a liver resection, it will be carried out under a general anaesthetic. There are two ways to perform the surgery:

- in open surgery, the surgeon makes a large cut in the upper abdomen under the rib cage. This is the most common type of surgery.

- in keyhole (laparoscopic) surgery, the surgeon makes a few small cuts in the abdomen, then inserts a thin instrument with a light and camera (laparoscope) into one of the cuts. Using images from the camera as a guide, the surgeon inserts tools into the other cuts to remove the cancerous tissue.

How a PVE is done

In some cases, you may need a portal vein embolisation (PVE) before a liver resection. A PVE blocks the branch of the portal vein that carries blood to the part of the liver that is going to be surgically removed. Blocking the blood supply allows the other part of the liver to grow bigger.

1. The interventional radiologist inserts a tube (catheter) through the skin. Using ultrasound as a guide, a dye is injected to identify the portal vein. Then the targeted branch will be blocked with tiny plastic beads, soft gelatine sponges or metal coils.

2. Blood is redirected to the part of the liver that will be kept to help it grow.

3. After 4–8 weeks, you will have a CT scan to measure the size of your liver. If the liver has grown enough to safely do a liver resection, the surgeon will remove the part of the liver with the tumour.

What type of surgery will I have? – People who have laparoscopic surgery usually have a shorter stay in hospital, less pain and a faster recovery time. However, laparoscopic surgery is not suitable for everyone with primary liver cancer and it is not available in all hospitals. Both open surgery and laparoscopic surgery are major operations – talk to your surgeon about the best option for you.

What to expect after surgery – The portion of the liver that remains after the resection will start to grow, even if up to two-thirds of the liver has been removed. It will usually regrow to its normal size within a few months, although its shape may be slightly changed. After surgery:

- Bleeding is a risk because a lot of blood passes through the liver. You will be monitored for signs of bleeding and infection.

- Some people experience jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes). This is usually temporary and improves as the liver grows back.

- Most people will need a high level of care. You will spend 5–10 days in hospital after a liver resection and it is common to spend some time in the high dependency or intensive care unit before moving to a standard room.

Liver transplant

A liver transplant can be an effective treatment for some people with primary liver cancer. It involves removing the whole liver and replacing it with a healthy liver from another person (a donor). However, liver transplants are suitable for only a small number of people. Those with a single tumour or several small tumours may be able to have a transplant. A liver transplant may also be considered if other therapies such as TACE can shrink the tumour first. This is called downstaging.

To be considered for a liver transplant, you also need to be reasonably fit, not smoke or take illegal drugs, and have stopped drinking alcohol for at least six months.

Liver transplants are not possible when the cancer has spread (metastasised) to other organs or to major blood vessels.

Currently, all liver transplants in Australia are performed in public hospitals and there is no cost for in-hospital services. You will usually have to pay for any medicines you continue to take once you leave the hospital after the transplant.

Waiting for a liver transplant – Donor livers are scarce and waiting for a suitable liver may take many months or even several years. During this time, the cancer may continue to grow. As a result, most people have tumour ablation or TACE to control the cancer while they wait for a donor liver to become available.

Unfortunately, in some people the cancer progresses despite having tumour ablation or TACE, and a liver transplant will no longer be possible. If this happens, you will be taken off the liver transplant waiting list and your doctor will discuss other treatment options.

What to expect after a transplant – If you have a liver transplant, you will spend up to three weeks in hospital. It may take 3–6 months to recover and it will probably take time to regain your energy.

You will be given medicines called immunosuppressants to stop your body rejecting the new liver. These drugs need to be taken for the rest of your life.

Tumour ablation

For tumours smaller than 3 cm, you may be offered tumour ablation. This destroys the tumour without removing it and may be the best option if you cannot have surgery or are waiting for a transplant.

Ablation can be done in different ways depending on the size, location and shape of the tumour. Thermal ablation and alcohol injection are the most common methods used for liver cancer. Cryotherapy, which uses freezing to destroy the tumour, is rarely used.

Thermal ablation – This ablation method uses heat to destroy a tumour. The heat may come from radio waves (radiofrequency ablation or RFA) or microwaves (microwave ablation or MWA). Using an ultrasound or CT scan as a guide, the doctor inserts a fine needle through the abdomen into the liver tumour. The needle sends out radio waves or microwaves that produce heat and destroy the cancer cells.

Thermal ablation is usually done under general anaesthetic in the x-ray department or the operating theatre. Treatment may take 1–2 hours. Some people may stay overnight in hospital, but many can leave the hospital after treatment. Side effects may include pain, nausea or fever, but these can be managed with medicines.

Alcohol injection – This ablation method involves injecting pure alcohol (ethanol) into the tumour. This procedure – called percutaneous ethanol injection or PEI – isn’t available at all hospitals but may be used if other forms of ablation aren’t possible. For this procedure, a needle is passed into the tumour under local anaesthetic, using an ultrasound as a guide. You may need more than one injection over several sessions. Side effects are rare but may include pain or fever. These can be managed with medicines.

Radiation therapy

Primary liver cancer is sensitive to radiation but so are healthy liver cells. Two specialised techniques can deliver radiation directly to the tumour while limiting the damage to the healthy part of the liver. These are called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT). SBRT may be suitable for people with early-stage cancer, while SIRT may be offered in more advanced cases.

Conventional external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is also occasionally used as a palliative treatment to help manage symptoms. For example, short courses of EBRT can help to control pain caused by liver cancer that has spread to the bones.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

This type of therapy may be called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) or stereotactic ablative body radiation therapy (SABR). It is a type of EBRT. The machine precisely targets beams of radiation from many different angles onto the tumour.

SBRT is prescribed by a radiation oncologist and delivered in a radiation therapy department. This method allows a high dose of radiation to be delivered to the tumour while surrounding healthy tissue is protected from the effects of radiation. SBRT requires fewer treatment sessions than conventional radiation therapy. People may need only 3–8 sessions over one or two weeks.

This treatment may be offered to people with tumours that can’t be removed with surgery or treated with tumour ablation or TACE. SBRT may also be used to shrink tumours while people are waiting for a liver transplant.

How SBRT is done

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) precisely targets beams of high-dose radiation from different angles onto the tumour.

Before this treatment, you will have a CT scan and maybe an MRI scan as well. These scans help make an individual plan for your treatment. You may also need a short procedure to insert small metal markers (called fiducial markers) next to the tumour. These markers allow the radiation oncologist to monitor the exact position of the tumour during the treatment. They are usually made of gold and are about the size of a grain of rice. A needle is used to put in the markers during the CT scan. Not all people will need to have these markers inserted.

During treatment, you will be asked to lie on a treatment table while a machine delivers the targeted beams to the tumour. It is important to lie very still during SBRT treatment. Simple breathing techniques – like holding your breath for 10–15 seconds – can help reduce movement during the procedure. Your treatment team will talk to you about this. SBRT itself is painless, and you can usually go home after the treatment. You will not be radioactive after SBRT.

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT)

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) is a different type of radiation therapy. Sometimes called radioembolisation, SIRT combines embolisation (which blocks blood supply to the tumour) with internal radiation, where the radiation source is placed inside the liver.

In SIRT, the radiation is delivered through the blood vessels to the tumour using tiny radioactive beads, which are made of resin or glass. The procedure may be offered for primary liver cancer when the tumours can’t be removed with surgery or to shrink tumours before a liver resection or a transplant.

SIRT is performed by an interventional radiologist, supported by a nuclear medicine physician, in a radiology department. One to two weeks before the procedure, you will have a work-up day to ensure the procedure is appropriate for you.

Work-up day – Several tests will be done on this day, including blood tests to check kidney function and blood clotting, and an angiogram (an x-ray of the blood vessels).

Before the angiogram, you will have a local or general anaesthetic. The interventional radiologist will then make a small cut in the groin area and insert a thin plastic tube (called a catheter) into the artery that feeds the liver (hepatic artery). A small amount of dye (contrast) will be passed through the catheter into the bloodstream. On an x-ray, the dye provides a detailed map of the blood supply to the liver, which varies from person to person. The doctor may also block some small blood vessels. This helps to stop the radioactive beads travelling beyond the liver to other parts of the body when you have the SIRT treatment.

Next, a substance called a radiotracer will be injected into the catheter and you will have another scan. This scan shows where the radioactive beads will go on the day of treatment. It will also check if any beads are likely to travel to the lungs. This step helps the doctor work out if it is safe to go ahead with the treatment.

How SIRT is done

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) combines embolisation with internal radiation therapy.

Treatment day – On the day of treatment, you will have another angiogram. The interventional radiologist will make a cut in the groin area and pass a catheter through to the hepatic artery.

The radioactive beads will be inserted through the catheter into the hepatic artery. These beads can then deliver radiation directly to the tumour.

The procedure takes about an hour. You will be monitored after the procedure, and recover in hospital overnight.

After treatment – You may experience flu-like symptoms, nausea and pain, which can be treated with medicines. You can usually go home within 24 hours.

The radioactive beads will slowly release radiation into the tumour over the next week or so. During this time, you may need to take some safety precautions such as avoiding close physical contact with children or pregnant women. You may also be advised to not share a bed or have sex in the first few days after treatment.

Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE)

Liver tumours mostly get their blood supply from the hepatic artery. In transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), chemotherapy is delivered directly to the tumour through this artery.

TACE is usually given to people who can’t have surgery or ablation for primary liver cancer. The procedure may be used to shrink the cancer or stop it growing while people are waiting for a liver transplant or a major liver resection.

How TACE is done

Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) delivers chemotherapy directly to a tumour while blocking its blood supply (embolisation). It is done by an interventional radiologist.

1. Before TACE, you will have a local anaesthetic and possibly a sedative to help you relax.

2. The interventional radiologist will make a small cut in the groin, then pass a plastic tube called a catheter through the cut and into the hepatic artery.

3. The chemotherapy drugs are injected into the liver through the catheter. The chemotherapy will either be mixed with an oily substance or loaded onto tiny plastic beads. The blood vessel feeding the tumour may also be blocked.

4. After TACE, you will have to remain lying down for about 4 hours. You may also need to stay in hospital for a night or a few days.

5. You will have a CT or MRI scan about 4-12 weeks after the procedure to see how well the treatment has worked.

Side effects of TACE – It is common to have a fever the day after the procedure, but this usually passes quickly. You may experience nausea and vomiting, or feel some pain, which can be controlled with medicines. Some people feel tired or have flu-like symptoms for up to a week after the procedure.

Drug therapies

Two types of drug therapy are available to treat primary liver cancer: immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

Drug therapies (sometimes called systemic therapies) can spread throughout the whole body to treat cancer cells wherever they may be, which can be helpful for cancer that has spread (metastatic cancer).

Immunotherapy

This is a type of drug treatment that helps the body’s own immune system to fight cancer cells. Immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors block proteins that stop immune cells from recognising and destroying the cancer cells. Once the proteins are blocked, the immune cells can recognise and attack the cancer.

A checkpoint inhibitor called atezolizumab is an immunotherapy drug subsidised on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) to treat some types of primary liver cancer.

Atezolizumab, which is given in combination with a targeted therapy drug called bevacizumab, is often the first drug treatment used for primary liver cancer.

Immunotherapy drugs are delivered by drip into a vein (intravenously), which may take 1–3 hours. Treatments are usually given every three weeks; your doctor will discuss with you how often and how many treatments will be needed.

Side effects – Immunotherapy can have different side effects for different people. These mostly happen when the immune system becomes overstimulated and attacks organs such as the skin, bowel, liver or hormone-producing glands.

These immune-related side effects can happen when you are having treatment or in the weeks, months, or even years, afterwards. In rare cases, side effects can be the sign of serious complications, so even mild side effects should be reported to your doctor.

Immune-related side effects may need to be treated with drugs to help control the immune response (called immunosuppressive drugs), and the immunotherapy may need to be stopped.

If you are unable to manage the side effects of immunotherapy, your doctor may recommend switching to targeted therapy.

When you start immunotherapy, you may be given an alert card so you can let all health professionals know that you are having this treatment. This ensures that you are given the best treatment if you develop side effects.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Immunotherapy’

Targeted therapy

This type of treatment targets specific features of cancer cells to stop the cancer growing and spreading. People who have advanced liver cancer and are unable to take immunotherapy may be offered targeted therapy drugs such as sorafenib or lenvatinib.

These drugs are both subsidised by the PBS for some types of primary liver cancer. They are given as tablets that you swallow. Your doctor will explain when to take them.

Side effects – The side effects of sorafenib and lenvatinib may include skin rash, diarrhoea, fatigue and high blood pressure. These side effects can usually be managed without having to completely stop treatment.

Your treatment team will monitor you while you are taking targeted therapy drugs. If you find the side effects of targeted therapy difficult to manage, your doctor may recommend switching to another drug.

Generally, targeted therapy is continued for as long as there is benefit. If liver cancer progresses despite treatment with sorafenib or lenvatinib, your doctor may talk to you about trying another targeted therapy drug.

Download our fact sheet ‘Understanding Targeted Therapy’

Drug treatment for advanced liver cancer is changing quickly and new treatments may become available in the near future. You may also be able to get new drugs through clinical trials. Talk to your doctor about the latest developments and whether there are any suitable clinical trials for you.

Palliative treatment

If liver cancer is advanced when it is first diagnosed or returns after initial treatment, your doctor will discuss treatment options to help control the cancer’s spread and relieve symptoms.

Palliative treatment helps to improve people’s quality of life by managing the symptoms of cancer when a cure is not possible. It is best thought of as supportive care. Many people think that palliative treatment is for people at the end of their life, but it may help at any stage of advanced liver cancer. It is about living as long as possible in the most satisfying way you can.

Treatment may include radiation therapy; pain management; insertion of a stent in the bile duct to relieve jaundice; or drainage of fluid (ascites).

Palliative treatment is one aspect of palliative care, in which a team of health professionals aims to meet your physical, emotional, cultural, social and spiritual needs. The team also supports families and carers.

Download our booklet ‘Understanding Palliative Care’

Download our booklet ‘Living with Advanced Cancer’

"I’d like people with advanced cancer to know that there are a myriad of services. You only have to ask; you are not alone.” PAT

Managing symptoms

Primary liver cancer can cause various symptoms, but there are ways to manage them. With advanced cancer, the palliative care team may be involved in managing symptoms.

Jaundice

One of the liver’s jobs is to process bilirubin, a yellow pigment formed when red blood cells in the body break down. Normally, the bilirubin passes from the liver, through the bile duct to the bowel, and then out of the body in faeces (poo).

With liver cancer, bilirubin sometimes builds up in the blood. This can be because the cancer has blocked a bile duct, the liver is not working properly, or the liver has been replaced by widespread tumour. The build-up of bilirubin in the blood is known as jaundice. It can cause yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, pale faeces, dark urine and itchy skin.

This itching is often worse at night. It can be relieved to some degree by keeping your skin moisturised, and avoiding alcohol, spicy food, hot baths and direct sunlight. If the itching continues, your doctor may prescribe medicine, which can sometimes help.

When jaundice is caused by a blocked bile duct, it may be relieved by unblocking the duct with a small tube made of plastic or metal (a stent). Symptoms of jaundice usually go away 2–3 weeks after the stent is put in place. The earlier the stent is inserted, the less severe the symptoms. Stenting is not always recommended or possible in advanced cancer.

Pain

In some people, liver cancer can cause pain in the upper right area of the abdomen (belly) and, sometimes, in the right shoulder. If the cancer has spread outside the liver, pain may also occur in the ribs, back or pelvis.

Pain can be managed with different types of pain medicines. These may be mild, like paracetamol, or strong and opioid-based, like morphine, hydromorphone or fentanyl. Some pain medicines, such as ibuprofen and aspirin, may not be suitable for pain caused by liver cancer. Speak to your doctor about this.

Pain can also be managed with radiation therapy (to reduce the size of a liver tumour) or a nerve block (when an anaesthetic is injected into the nerve). You may also be referred to see a pain or palliative care specialist.

How to cope with pain

- Keep track of your pain in a symptom diary.

- Allow a few days for your body to adjust to the dose of pain medicine and for any drowsiness to improve.

- Let your doctor know if you have vivid dreams, nausea or other side effects after taking a strong pain medicine such as morphine. The doctor can adjust the dose or you can try other pain relief methods.

- If you are taking an opioid based drug like morphine, use a laxative to prevent or relieve constipation.

- Take pain medicine as prescribed, even when you’re not in pain. Managing pain may become more difficult if pain medicine is not taken regularly.

Poor appetite and weight loss

Because the liver plays a key role in the digestive system, cirrhosis and cancer in the liver can affect how much you eat, and you may lose weight. Radiation therapy and other cancer treatments can also have an impact on appetite and weight, especially if you have side effects such as nausea and vomiting, mouth ulcers, and taste or smell changes.

Maintaining your weight can help your recovery, so it’s important to eat and drink enough during and after treatment. Gentle physical activity, like a short walk around the block, can help to stimulate your appetite, and eating a variety of foods may boost how much you are able to eat.

Your doctor may suggest that you avoid salty foods as these can increase the risk of ascites (fluid build-up).

How to stay well nourished

Eat foods you enjoy – Eat foods that you like, but also try eating different foods. Your taste and tolerance for some foods may have changed and may continue to change. Chew foods well and slowly to avoid becoming too full.

Drink fluids – Prevent dehydration by drinking fluids, such as water, between meals (e.g. 30–60 minutes before or after meals). Avoid filling up on fluids at mealtimes – unless it’s a hearty soup – to ensure you have room for nourishing food.

Talk to a dietitian – Ask your dietitian what foods you can eat to increase your energy and protein intake.

Get help – Ask your family and friends to cook for you and offer you food throughout the day.

Snack during the day – Try eating 5–6 small meals rather than three large ones each day. Keep a selection of snacks handy (e.g. in your bag or car).

Download our booklet ‘Nutrition for People Living with Cancer’

Fatigue

Many people with primary liver cancer experience fatigue. This is different to normal tiredness as it doesn’t always go away with rest or sleep. The fatigue may be a side effect of treatment or caused by the cancer itself. Managing fatigue is an important part of cancer care.

Download our fact sheet ‘Fatigue and Cancer’

Listen to our podcast episode ‘Managing Cancer Fatigue’

"After treatment, a psychologist explained that it’s common to feel like you have had the rug pulled out from underneath you.” JOHN

Fluid build-up

Ascites is when fluid builds up in the abdomen. In people with cirrhosis, pressure can build up in the blood vessels inside the liver, which may force fluid to leak into the abdomen.

Ascites can also be caused by the cancer itself blocking lymph or blood vessels or producing extra fluid. The fluid build-up causes swelling and pressure in the abdomen. This can be uncomfortable and may make you feel breathless.

Initial treatment may include reducing salt intake in your diet and the use of diuretics (sometimes called water or fluid tablets) to reduce fluid in the body.

If needed, a procedure called paracentesis or ascitic tap can also provide relief. Your doctor will numb the skin on the abdomen with a local anaesthetic. A thin needle and plastic tube are then placed into the abdomen, and the tube is connected to a drainage bag outside your body. Sometimes, an ultrasound scan is used to guide this procedure. It will take a few hours for all the fluid to drain into the bag, and then the tube will be removed from your abdomen. Diuretics may be prescribed with paracentesis to slow down the build-up of fluid.

Confusion

In people with cirrhosis, toxic substances can sometimes build up in the blood and affect how your brain functions. Called hepatic encephalopathy, this can lead to confusion or disorientation and, in severe cases, coma. Carers need to look out for these symptoms as this condition can develop quickly. Hepatic encephalopathy can be controlled with medicines.

Life after treatment

For most people, the cancer experience doesn’t end on the last day of treatment. Life after cancer treatment can present its own challenges. You may have mixed feelings when treatment ends, and worry that every ache and pain means the cancer is coming back.

Some people say that they feel pressure to return to “normal life”. It is important to allow yourself time to adjust to the physical and emotional changes, and establish a new daily routine at your own pace. Your family and friends may also need time to adjust.

Cancer Council 13 11 20 can help you connect with other people who have had liver cancer, and provide you with information about the emotional and practical aspects of living well after cancer.

Follow-up appointments

After treatment ends, you will have regular appointments to monitor your health, manage any long-term side effects and check that the cancer hasn’t come back or spread. During these check-ups, you will usually have a physical examination and you may have blood tests, x-rays or scans. You will also be able to discuss how you’re feeling and mention any concerns you may have.

People who still have hepatitis B or hepatitis C may be given medicines (antiviral therapy) to help manage these diseases and reduce the chance of the cancer coming back. Your doctor will also talk to you about the importance of not drinking alcohol, not smoking, eating healthy foods and exercising.

Check-ups will become less frequent if you have no further problems. Between follow-up appointments, let your doctor know immediately of any symptoms or health problems.

When a follow-up appointment or test is approaching, many people find that they think more about the cancer and may feel anxious. Talk to your treatment team or call Cancer Council

13 11 20 if you are finding it hard to manage this anxiety.

What if the cancer returns?

For some people, liver cancer does come back after treatment, which is known as a recurrence. The cancer may come back in the liver, in nearby organs or in other parts of the body. This is why it’s important to have regular check-ups. You may be offered more treatment and may include drug therapy or the insertion of a stent. Treatment will depend on the type of cancer you have, where it has spread, your general health and the types of treatment you have had before.

When cancer won’t go away

For many people with primary liver cancer, the cancer cannot be cured. Talking to your health care team can help you understand your situation and plan for your future care. Palliative treatments may help control the growth of the cancer and manage the effects of cancer and/or its treatment. These treatments may allow you to continue doing the things you enjoy for months or even several years.

Learning that the cancer may not be cured can be very upsetting. You can call Cancer Council

13 11 20 for support and information or talk to the social worker or spiritual care practitioner (such as a chaplain) at your hospital or treatment centre.

Download our booklet ‘Living with Advanced Cancer’

Download our booklet ‘Facing End of Life’

Listen to our podcast series ‘The Thing About Advanced Cancer’

"There is still a life to be lived and pleasures to be found and disappointments to be had. Living with advanced cancer is a different life, not just a journey towards death.” JULIE

Dealing with feelings of sadness

If you have continued feelings of sadness, have trouble getting up in the morning or have lost motivation to do things that previously gave you pleasure, you may be experiencing depression. This is quite common among people who have had cancer.

Talk to your GP, because counselling or medication—even for a short time—may help. Some people can get a Medicare rebate for sessions with a psychologist. Cancer Council SA operates a free cancer counselling program. Call Cancer Council 13 11 20 for more information.

For information about coping with depression and anxiety, visit Beyond Blue or call them on

1300 22 4636 . For 24-hour crisis support, visit Lifeline or call them on 13 11 14.